Dispute resolution and redress

20.08.2020Existing arrangements

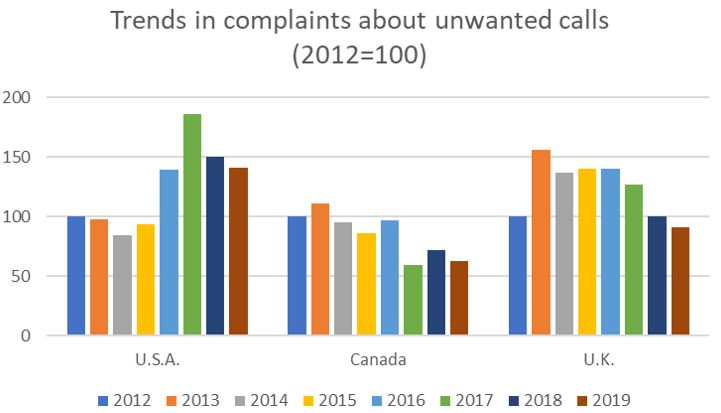

Source: Antelope Consulting.

Ensuring that consumers’ complaints about providers are dealt with in a fair way is an important continuing duty for most ICT regulators. This is why a 2019 ITU Global Symposium for Regulators (GSR) Discussion Paper focused on dispute resolution and redress. It identified different types of dispute handling mechanism, as shown in the box below.

|

Consumer dispute handling mechanisms

|

Source: Horne 2019.

Where a dispute is resolved in favour of the complainant, redress (or remedy) is usually required from the provider – that is, an action to put right what has gone wrong, as far as feasible. Often, this involves money – at minimum, paying back any amount that has been overcharged, and sometimes also paying larger amounts aimed at compensating for wider financial losses, for example, lost business during a period without connectivity. Complainants may also request compensation for harm that is less easily quantified, for example, for distress caused by losing contact with sick family members, or in extreme cases for lasting consequences of having been unable to call for help in an emergency. Dispute resolution schemes may exclude this type of compensation on the grounds that it is too difficult to assess fairly, or specify set amounts or bands of compensation for harm regarded as low/moderate/significant. But often, complainants are most interested in action – for example, to fix a long-standing fault, or to put them back with their original provider after a mistaken transfer – together with an apology, and an assurance of efforts to prevent the problem recurring.

A common arrangement is that aggrieved consumers should first complain to the provider of the services or product that is causing dissatisfaction, and if they are not happy with the outcome, then proceed to a further stage. Regulators are commonly involved in this further stage, either themselves resolving the complaint (typically by adjudication) or referring the complaint to an approved body which fulfils one or more of the roles (ii) to (vi) in the box above. These are often known as alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, where “alternative” means “other than the courts”. ADR is a skilled profession requiring specific training.

ADR is often practised online (as opposed to in person or on paper) and, in this case, it may be called online dispute resolution (ODR). ODR is especially appropriate for e-commerce and cross-border disputes. The U.S.-based National Center for Technology and Dispute Resolution, founded in 1998, soon got involved with the online marketplace eBay, which now gives rise to around 60 million disputes a year settled via this service. Any system of this kind depends for its success on the provider promising to accept the decisions reached, and the consumer knowing about the system and being able to use it.

Many advanced jurisdictions now cater for collective complaints, also known as group actions or super-complaints (leading to collective redress). They originated long ago in the United States and are now available in most European countries, though not on a uniform basis. They are a powerful tool for consumer organizations, who can make complaints on behalf of large numbers of affected individuals. With professional back-up and shared resources, they have a much better chance of success and can have far greater impact than complaints by individuals. Depending on the amounts at issue, a successful case for collective redress may lead to financial payouts to all those affected, but high administrative costs may mean that it makes more sense for the sums due to be paid to a body that supports consumers or other agreed cause. Such cases may also lead to changes in the rules, as in the example shown below.

|

Example of collective redress in the United Kingdom The U.K. consumer organization, Citizens Advice, took advantage of the EU-led legislation on collective redress to make a super-complaint in October 2017 concerning overcharging of loyal mobile phone customers. As a result, Ofcom responded and made changes to how mobile operators behaved. In May 2019, Ofcom issued a statement on end-of-contract notifications and annual best tariff information, Helping consumers get the best deal. The regulation will mean broadband, mobile, home phone, and pay-TV companies must notify their residential and business customers when their minimum contract period is coming to an end. These notifications will tell residential customers about the best tariffs available from their providers. Business customers will be given best tariff information in a form that is suitable for them. Customers who remain out-of-contract will also be given best tariff information by their provider at least annually. |

Source: Adapted from Horne 2019.

In many developing countries, complaints volumes are still fairly low and ADR is within the capacity of the regulator. As an example, ARCEP Benin provides for complaints via a range of input media – by phone (using the free-of-charge short code 131), paper post, online (by email or web form), or in person at their reception desk. Complaints are input to a database which automatically notifies complainants when their cases reach certain stages.

The Australian arrangements are a good example of a complaints system with an independent ADR body in an advanced economy with a large digital sector and a high volume of complaints (illustrated in the opening figure to this article). There is a memorandum of understanding (MoU)[1] between the regulator ACMA and the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman TIO. The MoU itself is a good example of regulatory collaboration, aiming to avoid duplication of tasks between the parties and to ensure good information sharing in both directions, in particular keeping ACMA abreast of complaints trends and the systemic problems they may reveal.

When (re)designing a suitable scheme for resolving consumer complaints, the criteria in the box below are widely thought to be applicable (UNCTAD 2019, 88).

|

Desirable features of a consumer dispute resolution scheme

|

Source: UNCTAD 2019.

Looking to the future

UNCTAD’s consumer protection work programme now includes a project called Consumer Rights Beyond Boundaries, aiming to put digital technologies (specifically, blockchain) at the service of consumer dispute resolution. The project, based at the University of Oxford and with an international team of advisers, started work in 2019 and appears to be the latest stage of the previous consumer redress project.

A recent report by the U.K. NGO, Doteveryone, and the consumer support organization, Resolver concluded:

“Better redress is not a nice to have in the digital age. It’s the cornerstone of a fair, inclusive and sustainable democratic society.”

Its recommendations are summarized in the box below.

|

Recommendations of Better Redress for the Digital Age We recommend all tech companies create accessible and straightforward ways for people to report concerns and provide clear information about the actions they take as a result. We recommend the incoming online harms regulator provide robust oversight of companies’ complaints processes founded on seven principles of better redress in the digital age: 1. Design that’s as good as the rest of the service 2. Signposting at the point-of-use 3. Simple, short, straightforward processes 4. Feedback at every step 5. Navigating complexity 6. Auditability and openness 7. Proportionality We also recommend that digitally-capable super-complainants should act on the public’s behalf to demand collective redress from technology-driven harms. They will drive the structural changes required within online services and help channel unresolved disputes between individuals and companies. And we call on the Government for financial support to unlock the expertise of civil society to support people to address the impacts of technology-driven harms on their lives. Coordinated action between charities and support groups can help people to seek redress and encourage improved understanding of the nature of online harms. |

Source: Doteveryone 2020.

Endnotes

- A news item at available here explains changes in the MoU in 2020 following a review. ↑

References

Doteveryone. 2020. Better Redress for the Digital Age. London. https://www.doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Better-Redress-for-the-Digital-Age-1.pdf.

Horne, Alan G. 2019. Building Confidence in a Data Driven Economy by Assuring Consumer Redress. GSR Discussion Paper. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Conferences/GSR/2019/Documents/Consumer-Redress-digital-economy_GSR19.pdf.

Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman. 2019. Annual Report 2018-19. Melbourne. https://www.tio.com.au/sites/default/files/2019-09/TIO%20Annual%20Report%202018-19.pdf.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2019. Manual on Consumer Protection. Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditccplp2017d1_en.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022