Consumer affairs in general

19.08.2020Basic consumer rights

The concept of consumer rights has been with us since humans began bartering goods and services over 150,000 years ago. Based on widespread notions of fairness in trading, human societies have agreed, for example, that a kilogram weight should in fact weigh 1000 and not 900 grams, that products should be truthfully described and be fit for purpose (e.g. flour should not contain chalk powder), and that promises to sell at a certain price should be kept.

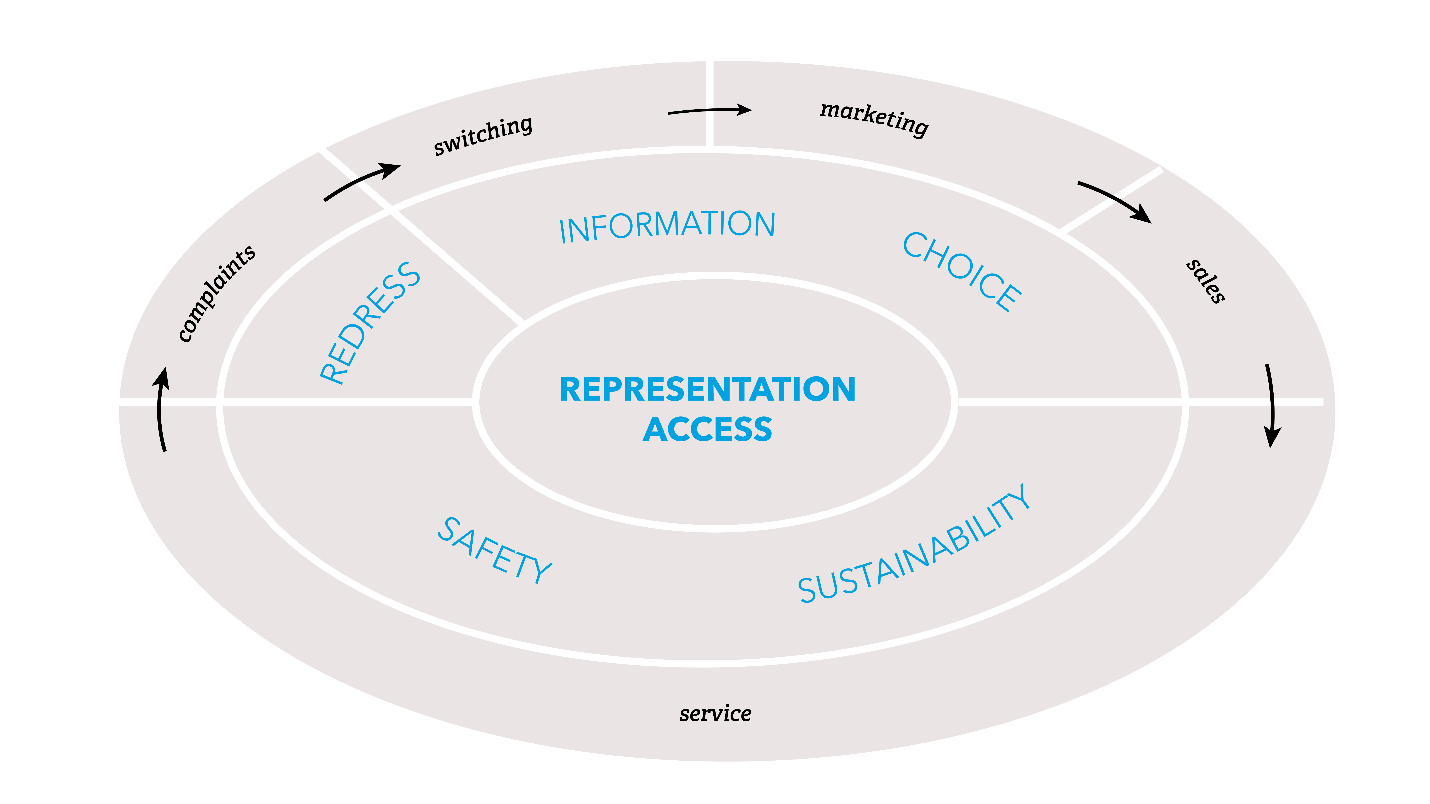

The development of consumer rights as now understood, however, started only in the twentieth century. More choice of household goods led to the spread in developed countries of product testing by consumer organizations, which published the results to help people to make good buying decisions. In 1962, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, in a famous speech, set out a seven basic consumer rights, which apply across all sectors: access, choice, information/education, safety, redress, sustainability, and representation.

Over intervening decades, these rights have been extended and developed, and are now seen as essential to achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (UNCTAD 2017). Discussions of their latest version can be found in the UNCTAD Consumer Protection Guidelines (UNCTAD 2016), while the Manual (UNCTAD 2019) provides much more background and guidance on their application, though not specifically to digital products and services.[1] Security and privacy, which may be seen as aspects of safety, have acquired special relevance for digital activities.

The rights are more relevant at different stages of the consumer journey, as shown in the diagram below. The outer ring shows provider activities, and the inner rings relevant consumer rights. As the consumer proceeds from each to the next, different rights become more important – information and choice matter most to the switching, marketing, and sales stages; safety and sustainability matter most to the service stage (which normally has the longest duration); and redress matters most to the complaints stage (if any). Representation and access are important for all stages.

Consumer empowerment and consumer protection

The consumer rights exercised in the earlier stages of this journey (marketing and sales) can be seen as those needed for consumer empowerment, while those exercised in the later stages (service, complaints, and switching) require consumer protection. The latter, in turn, consists of both prevention and cure of harm. Regulators’ duties in respect of consumers often start with consumer protection (ensuring safety and redress), and only later extend to consumer empowerment (through information, education, and representation).

As in health care, however, preventing problems is usually better and cheaper than having to deal with problems that have arisen. Empowered consumers are more likely to choose services well and use them wisely, and then have less need for consumer protection. Effective regulators will pay attention to both empowerment and protection.

Some terminology

Before going further, this article explains what is meant by the term consumer and how its meaning differs from other terms that regulators often use in similar contexts.

Anyone who uses communications for any purpose can be called a user. Anyone who uses services for their own purposes, rather than as part of a package offered to others, is an end user. So, for example, an app provider who buys in and packages messaging as part of their app, which they sell, would be a user but not (in that capacity) an end user.

Anyone who pays for services is a customer of the provider. Customers are usually, but not always, also users; for example, in a company or household, one person may pay the bills while others use the services. Providers often divide their customer base into business customers and residential customers. Businesses here usually include all kinds of organization (such as government departments) and can be large, medium, or small. These size divisions are often made by national statistical services, so they vary; typically, a large business might have more than 250 employees and a small one 10 or fewer employees.

In law, consumers often refers to customers who are buying for end use, rather than for onward sale. Regulatory duties (based in economic theories) often require regulators to have special concern for the interests of consumers. However, sometimes it is assumed that large businesses are able to look after themselves. Then the regulator may be charged with concern for the interests of small and medium enterprises (SME) or just small enterprises, along with residential consumers (who are buying for their households) and personal consumers (who are buying for themselves). In the Handbook, consumers usually refers to residential and personal consumers, though sometimes small and very small businesses are referred to. Very small (or micro) businesses would include sole traders, who often cannot be distinguished from individuals – many people use the same phone in their work and personal lives.

Often regulatory duties include extra concern for groups of consumers thought to be vulnerable, such as those who are disabled or older people. Regulators may also be tasked with looking after the interests of citizens. Citizens are usually the same people as consumers, but in different roles: citizen interests are to do with the good of the community or country, while consumer interests are to do with the good of the individual or household. So, someone who is happy with their own services but wants good universal service policies for the country would be seen as a citizen rather than a consumer.

Sample consumer protection legislation

Zimbabwe’s Consumer Protection Bill (Government of Zimbabwe 2018) is a useful example of general consumer protection legislation. It brings together in one place and rationalizes a range of previous relevant instruments, and adds to them in the light of recent developments. The contents have been subject to public consultation. Notably:

- the Bill sets up a Consumer Protection Agency, managed by a Consumer Protection Committee whose members represent specific interests including those of consumers. The Agency’s mandate includes implementing the principles underlying the Bill and enforcing provisions of the Bill.

- the Bill provides for accreditation of Consumer Protection Advocacy Groups and designation of Consumer Protection Organisations (whose functions include dispute resolution).

- in 43 separate clauses, the Bill details fundamental consumer rights which apply to consumer transactions in general. These are divided into sections dealing with:

- the right to education,

- the right to health and safety,

- the right to choose, and

- the right to information.

- in a further three clauses, the Bill extends these rights to electronic consumer transactions.

From a digital viewpoint, the following provisions are especially worth noting:

- a cooling-off period when direct marketing has been used, giving consumers rights to rescind such transactions without penalty within five business days of receipt of the goods, or seven days in the case of electronic transactions.

- the right to block direct marketing approaches and unsolicited electronic communications.

Endnotes

- See “Consumer rights in the digital context” for more detail on how these rights are interpreted for digital. ↑

References

Government of Zimbabwe. 2018. Consumer Protection Bill. Harare. http://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/Consumer%20Protection%20Bill%202018%20-%20HB%2010-2018.pdf.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2016. Guidelines on Consumer Protection. Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditccplpmisc2016d1_en.pdf.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2017. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Consumer Protection. Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditccplp2017d2_en.pdf.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2019. Manual on Consumer Protection. Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditccplp2017d1_en.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022