Technical regulation – Quality of service

13.08.2020Introduction

What is quality of service?

People everywhere depend on ICT services. Unless these services are good enough, people need face-to-face contact in order to hold conversations, send and receive messages, obtain news, transfer money, play games, monitor and control machines, take part in markets, meetings, lessons, and entertainment, and so on. The range of services continues to grow.

What “good enough” means depends on many factors, such as user feelings and expectations, which themselves vary with applications and environments. To be good enough, services usually have to be not annoying, even if they are not delightful. In the words of ITU-T Recommendation P.10/G.100, the quality of experience (QoE) is “the degree of delight or annoyance of the user of an application or service” (ITU-T 2017).

Assessments of quality find out the degree of delight or annoyance under certain circumstances. Just as the range of services continues to grow, so does the range of assessments of quality; for instance, there are now standards for assessing the quality of over-the-top (OTT) streaming of multimedia to both televisions and smartphones and for designing tests of the quality of digital financial services (ITU-T 2020b; ITU-T 2020c).

The quality of service (QoS) restricts attention to some of the factors on which the quality of experience depends; it is defined to be “the totality of characteristics of a telecommunications service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated and implied needs of the user of the service” (ITU-T 2017).

QoE and QoS relate to both information technologies and communication technologies. For instance, the users of interactive systems are interested in the speeds with which the systems respond, not in how the responses are produced, and parts of the systems might be “in the cloud”, not on the user terminals (in what in earlier jargon were client-server relationships with thin clients): both the speed of transmitting information and the speed of processing information are important.

“Quality of service” and similar terms have been used in many ways over many years. In some documents (such as specifications of WiMAX), “quality of service” refers to techniques for managing traffic having particular types, such as voice or video; in other documents, “class of service” and “type of service” are used for this purpose, while “grade of service” refers specifically to successful call set-up. When QoS is used just to describe traffic management techniques, QoE is needed to assess how annoying or delightful ICT services are.

QoS as discussed here is closely connected with QoE and only indirectly related to traffic management techniques. However, QoE includes aspects of user characterization that QoS, as frequently understood, excludes.

Extra attention is devoted to QoE here because it is less known than QoS. Nonetheless, QoS remains relevant to whether, why, and how people use ICT services.

What should the regulator do?

Operators make many QoS assessments of their own, in their usual engineering activities and responses to customer complaints. If they have competitors they want to keep their market shares, so they look for the best combinations of quality and price and necessarily examine QoS. Of course, they might not do this if there is no competition or compulsion. Even if there is competition, there can be parts of the population that are poorly served and national needs that are not met.

In general, the regulator should be involved, with the purposes of:

- Informing users. Any checks on the claims made by operators need to be done by others. Any comparisons of quality between operators should use comparable measurements, which no one operator can provide. These checks and comparisons can help to redress the balance of information between customers and operators if they are publicized suitably.

- Restraining operators in strong competitive positions. Such operators might lower quality to raise revenues, especially if they have significant market power or are appointed to provide universal service. This is so for wholesale as well as for retail; for instance, an operator that controls the international gateway switches in a country is in a position to dictate interconnection service level agreements.

- Ensuring efficient use of scarce resources. People are entitled to know how well public property, such as the radio spectrum and rights of access to land, are being used. These are “scarce resources”: they might be exploited more or less efficiently but they do not expand. Using them well could entail serving diverse communities fully throughout the country.

- Assessing the national infrastructure. The infrastructure should be satisfactory for emergency support, business investment, human development and government services. No one operator is responsible for this; the regulator can take an overall view. Unaided, a competitive market might not fill the gaps in the infrastructure and might even lead to lower quality as all of the operators try to cut costs.

These purposes can delimit the scope of involvement of the regulator but do not determine the scale. The quality of services can differ greatly in different places and at different times. The services themselves vary enormously; assessing them is not always just a matter of calculating call completion rates. The regulator might have to select areas of involvement carefully or find ways of getting others to perform the assessments, either by working with the operators or by crowdsourcing.

The extent to which the regulator is involved depends on several factors, such as market maturity, financial constraints, political attitudes, and institutional arrangements. Even if the regulator does not make, audit or publish QoS measurements, there are ways in which the regulator and the operators together can perform some degree of monitoring.

QoS regulations can exist on paper but be ignored in practice. Regulators might not receive measurement results and might not enforce compliance. In those circumstances an operator might reach the targets but not feel a need to report the results.[1] Small countries where there are subsidiaries of large operators are particularly likely to suffer from them.

What are parameters and targets?

QoS is assessed by making measurements and checking whether the measurement results are satisfactory. The measurement results relate to:

- Parameters. These are quantities that can be measured to assess the quality of some aspect of the service. In other documents, they might be called “indicators”, “metrics”, “measures”, or “determinants”. Examples are “the successful call set-up ratio” (or “the proportion of call set-ups that are successful”) and “the average complaint resolution time” (or “the mean of the times taken to resolve complaints”).

- Targets. These are values of parameters for which the given aspect of the service is regarded as “good enough”; they might be intended to be reached immediately or within a certain timeframe. In other documents, they might be called “objectives”, “benchmarks” or “thresholds”. Examples are “97 per cent” (for a ratio, such as the successful call set-up ratio) and “6 hours” (for a time, such as the average complaint resolution time).

Usually international standards for QoS, from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) and other organizations, identify parameters and describe measurement methods but usually do not set targets. Also, in many countries, parameters are defined but targets are not set.

Among regional organizations, the Eastern Caribbean Telecommunications Authority (ECTEL) and the East African Communications Organisation (EACO) are unusual in identifying parameters for their member states. The parameters are intended for voice and data services and, In EACO, for digital financial services using certain Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD), Short Message Service (SMS), and Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) messages (EACO 2017).

The ITU has produced a manual on quality of service regulation intended mainly for regulators (ITU-D 2017). It includes many examples of parameters from countries across the world, as well as discussions of several other relevant topics. A shorter account of some of these topics can be found in ITU-T Recommendations Series E.800 Supplement 9 (ITU-T 2013a).

What does quality of service monitoring involve?

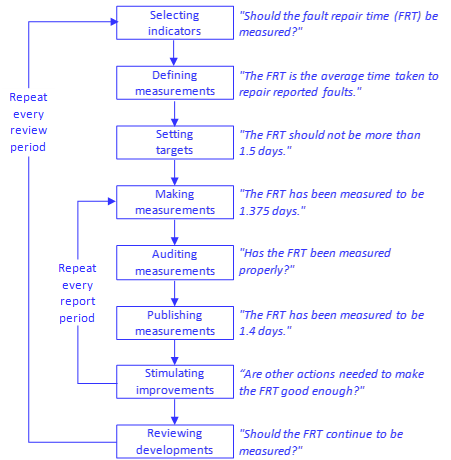

Figure 8.1 sets out the activities of regulators related to QoS monitoring, in a slight variant of a widespread flow chart.

Figure 8.1. Activities during QoS monitoring

Source: Adapted from ITU-D 2006.

The outer loop of activities, which is repeated in every review period, involves:

- Selecting parameters. The parameters selected for measurement should relate directly to the aspects of their experience that are most important to users.

- Defining measurements. The measurements should be defined so that different operators can be compared in the respects having significant implications for users.

- Setting targets. Any targets that are to be associated with the parameters should be set with a prior knowledge of what improvements in quality can reasonably be expected.

- Reviewing achievements. The achievements are examined at the end of the review period to see whether the intentions of QoS monitoring are being fulfilled.

The inner loop of activities, which is repeated in every reporting period, involves:

- Making measurements. The measurements are made by the operators, the regulator, or both the operators and the regulator. If the measurements are made by the operators, they are recorded and reported to the regulator at the end of the reporting period.

- Auditing measurements. The measurements might be audited by the regulator. If the measurements are made by the operators, often the regulator relies on self-certification by the operators (when senior managers in the operators certify the validity of the measurements) and occasional or annual checks, perhaps combined with drive and walk tests or crowdsourcing tests.

- Publishing measurements. The measurements are published by the operators, the regulator, or both the operators and the regulator. They can then also be publicized by journalists online and offline.

- Stimulating improvements. The improvements in quality might be stimulated in various ways, ranging from proposing improvement plans to imposing fines. In some circumstances, poor publicity from published measurements might provide enough stimulus.

Especially on the inner loop there can be bursts of activity that do not correspond neatly to reporting periods with constant lengths and frequencies. For instance, regulators might make measurements in particular places that had been neglected in network expansion or that had been responsible for many complaints, and in doing this they might need to forgo making measurements elsewhere.

Improvements in services, other than customer care, often require improvements in networks. Consequently, they need to be assessed only on a timescale like that for bringing about improvements; anything else can impose unnecessary burdens on the operators who make and report the measurements and on the regulators who audit or publish the results. This suggests leaving at least three months between QoS assessments. Accordingly, regulators often require that the operators report measurements quarterly. However, they themselves might make measurements annually, to investigate the circumstances in particular places or to check the reports by the operators.

There is a further discussion of these activities in the ITU manual on quality of service regulation (ITU-D 2017). They are also considered more in ITU-T Recommendation E.805 (ITU-T 2019a). They are looked at one-by-one in subsequent sections here, in the order in which they happen.

Selecting parameters

Regulators can get an initial view of how to concentrate their QoS monitoring from press reports, meetings with the public, contacts with consumer organizations, complaints to operators, and discussions with operators. Analysing social media posts can be illuminating but is complicated by potential exaggeration or misinformation.

In addition, regulators can conduct consumer surveys face-to-face, in telephone calls, or online, which need not be expensive or laborious. Even the answers to general questions, such as “how satisfied are you with the quality of the services that you receive?”, can be helpful. A simple example gives customer responses to nine questions about three services from three operators in two islands (CICRA 2019).

One especially thorough approach involves asking people to record their ICT activities in diaries. The diaries would indicate the relative importance of the activities, which could affect the priorities for QoS monitoring. The results can be detailed, with up to thirty different ICT activities for different age ranges, social groups, and genders in one case (Ofcom 2016).

The selection of parameters should satisfy the following criteria:

- Relevance to users. QoS monitoring is concerned more with user experience than with network performance. Operators might need to examine network performance parameters when designing their networks, but regulators, who do not design networks, do not need to do so. For instance, regulators need not require operators to report parameters about wireless handovers: these might be important to network designers but they are not directly relevant to users, who just want to know the proportion of calls that continue. In QoS monitoring, regulators are aiming to assess the QoS achieved by the operators against the QoE wanted by the users.[2] In summary, the QoS parameters monitored by regulators should be directly relevant to user experience.

- Importance to society. There might be some parameters that are of no immediate interest to individual users but are of importance to society as a whole. In particular, the national infrastructure should be satisfactory for emergency support, business investment, human development, and government services. Assessing the national infrastructure might entail, for example, knowing the call capacity on crucial network routes to ensure that enough calls could be made after disasters. Any need for such parameters should be considered by the working group on emergency telecommunication planning.

- Commonality between services. For purposes of QoS monitoring, different regulators group services in different ways; for instance, they might group fixed broadband with mobile broadband or they might separate fixed broadband from mobile broadband (in which case they will often ignore mobile broadband). The groupings reflect the particular circumstances of countries but make comparisons between countries difficult. However, some parameters can be the same for different services, especially if they relate to customer care.

- Independence of technology. Parameters should not depend on technology unless users regard the technology as characteristic of the services being monitored. For instance, voice calls remain voice calls, regardless of whether the underlying networks are fixed or mobile, so the parameters for telephony might be common to fixed and mobile services (and to traditional and OTT services). This is in line with the increasing substitution of mobile services for fixed ones, when user requirements on, and expectations of, telephony are largely independent of network technology.

By contrast, the parameters for service supply might be common to wireless and wireline services needing fixed access (as they are complicated mainly by visits to customer buildings) but disregarded for services needing mobile access.

- Minimality of requirements. QoS monitoring can be burdensome for both regulators and operators. Its costs should be weighed against its benefits. There are many parameters that could be monitored: eighty-eight are listed for customer care in ITU-T Recommendation E.803 (ITU-T 2011). However, customer complaints and customer surveys do not show a need for most of them: for instance, in the UK, for four services (fixed broadband, fixed telephone, mobile broadband and telephony, and subscription television) “not performing as it should” (often because of loss of service, poor delivery, or inaccurate advertising) and billing cause 75-95 per cent of complaints (Ofcom 2019).

Once parameters are selected they tend to remain when they are no longer needed; for instance, voice call set-up time is still reported in various countries where it is rarely high. If parameters become obsolete or unnecessary they should be discarded. This has been done in Brazil, for example.[3]

Further advice on selecting parameters can be found in ITU-T Recommendation E.802 (ITU-T 2007). It discusses the relations between different aspects of quality and the parameters that can be regarded as measuring those aspects from several viewpoints.

Defining measurements

Operators are likely to have already developed and implemented plans for regular QoS monitoring. Discussions with them, and with third parties that perform QoS monitoring for others, can enhance the understanding of the usefulness of particular parameters, the practicability of making and auditing measurements, and the realism of potential targets.

The following guidelines are relevant to the details of how to make measurements:

- Correspondence with usage. Measurements should be made at times and places to match user experience as far as possible. In particular, they should use data about actual user activity, not data from planning tools. Similarly, measurements should use data from potential user locations, not data from base stations, when they test activities such as call set-up that might fail before communications with the base stations can be established.

- Awareness of time and place. Large differences in quality can occur at different times of day, even within the working day, and at different seasons of the year. This can be a symptom that a service does not yet have enough users for statistical multiplexing to be effective: allocating more bandwidth is difficult to justify when there are few users, so the variation in demand is a high proportion of the allocated bandwidth.

Large differences in quality can also occur between places near each other that have different population densities, land uses, traffic, and environment. For instance, moving fast or being inside can attenuate signal strengths by 15 dBm (Marina et al 2015).

If differences in quality are large in different times and places then different measurement results are needed. The regulator and the operators together need to determine what these should be (typically after separating indoors, driving outdoors, and walking outdoors). In any event, the regulator should receive measurements annotated with their times and places.

- Comparability between operators. The measurements made by different operators and by the regulator can be compared fully with one another only if they are made in ways that are the same in all respects having significant implications for users. This can be difficult to achieve: not only do different operators make measurements in different times and places, they also have different practices and equipment. Simply naming parameters (as in many regulations and licences) rarely identifies the measurement methods precisely: standards can contain many options, and equipment vendors might use the same names for different network element counters.

- Representativeness. Often measurement results are formed from sampled values, typically by calculating the “mean” (or average) of the values. There is then always a sampling error. It is reduced by having a large enough sample to give confidence that the measurement result formed from it is close to the value that represents the user experience.[4] Ideally, the sample is large enough that different measurement results represent perceptibly different user experiences. This point is frequently ignored in reports on drive and walk tests by regulators, which give results for small districts without saying how many tests were performed in each of them.

- Perceptibility to users. Differences between measurement results that do not represent perceptible differences between user experiences might be said to be below a threshold, which is the “just noticeable difference”. The threshold is not independent of the measurement results: often, for given differences in measurement results, the differences between user experiences are more easily perceived if the measurement results are smaller (just as the difference between 2 and 3 per cent is perhaps more easily noticed than that between 97 and 98 per cent).

Means do not always summarize everything useful; for instance, a mean repair time might result from many fast repairs and some slow repairs. Hence, sometimes the most suitable parameter is not the mean of the sample but the maximum in a “quantile”, which is the proportion (such as 80, 90, 95, or 99 per cent) of the smallest values sampled. Taken together, the mean and the maximum in a suitable quantile can do much to characterize the sample; if just one of them is published, it will usually be the mean, because users are more likely to understand it.[5]

Setting targets

Parameters do not always need targets, as remarked in ITU-T Recommendation E.805 (ITU-T 2019a). The popularity of OTT voice services shows that many users are willing to sacrifice quality for economy: they prefer low prices with low quality to high quality with high prices. QoS requirements should not prevent users from choosing particular quality levels or operators from offering particular quality levels, regardless of whether they have traditional or OTT services.

Regulators can provide advice on quality levels (to both users and operators) without setting targets. However, setting targets can help to protect consumers when there is no practical choice between quality levels. This can happen because:

- There is a monopoly (or sometimes even an oligopoly with feeble competition), perhaps offering “universal service”.

- There is competition but switching costs discourage switching and quality levels have fallen without prices falling to match.

Useful advice on setting targets can be found in ITU-T Recommendation E.802 (ITU-T 2007). Targets that are realistic but demanding are often difficult to set. They should be introduced only after measurement of what is achievable; they could be made more demanding after every review period in which they are achieved.

Targets set in other countries need to be treated cautiously because the environments are different and the regulators might be ignoring their own rules.

Making measurements

Measurements might be subjective or objective, as described in ITU-T Recommendation E.802 (ITU-T 2007).[6] Here the focus is on objective measurements, as subjective ones are expensive and difficult to design for representative samples of users.

Measurements for a real network can be made in the network or in the field. A further classification of them is the following:

- System readings. These are obtained in the network from network nodes and support systems. They might require visits to outside plant, but more often they rely on collecting data centrally in network and support systems (though they could still involve customer equipment in tests, if the equipment is operating and open to operator intrusions). The data might be collected by the operator and forwarded to the regulator; alternatively, it might be collected by the regulator directly from a server inserted into the network of the operator. However, the data might not always represent the user experience fully; for instance, a network element count of wireless call attempts will not count the call attempts that fail because they never reach the base station.

- Campaign tests. These are performed in the field according to plans for particular times and places. The test equipment should use wireline or wireless connections to the networks like those that a customer would need. Campaign tests for fixed access are often done in the buildings or outside plant of the operators, to avoid needing access to houses and offices; campaign tests for mobile access are often drive and walk tests, done in vehicles or public spaces (such as shops and malls) using mobile phone arrays or special test equipment, with assumptions about extending the results into houses and offices. Though drive and walk tests are initiated by people alongside the equipment, similar tests of “unattended probes” might be initiated remotely when particular places require monitoring.

Drive and walk tests are expensive. To have confidence in them needs hundreds of tests, which should be repeated in every place where distinct results are wanted. To reduce costs, the regulator or the operators might choose an agent to conduct the tests for all the operators together. In the simplest arrangement, the regulator chooses the agent and recovers the costs from the operators in their normal fees (or in proportion to the number of tests per operator, for example). In an alternative arrangement, the operators choose the agent; the regulator can assist and reduce opportunities for delay by convening meetings of the operators and proposing ways of cost sharing. In either arrangement, the agent must be prepared to conduct tests for all of the operators on equal terms, so all of them can enjoy the same economies of scale and scope.

- Crowd tests. These are performed in the field by crowdsourcing. The terminals of users, or test equipment distributed to users, make measurements that collectively indicate user experience. Such tests are not matched for different operators: they are done wherever and whenever the users are present, and they might or might not be initiated by the users. Crowd tests for fixed access require personal computers or test equipment; crowd tests for mobile access require smartphones (unless they rely just on text messages to and from users). Though the tests might be initiated by users, the results are more likely to reflect the general situation if they are initiated automatically, not because of momentary user feelings.

A useful description of these techniques provides examples from French-speaking countries in Africa (Fratel 2019; Fratel 2020). It also mentions making estimates of quality from statements about coverage (typically as displayed in maps). If the statements about coverage are derived just from geographic and demographic information, then such estimates are not substitutes for measurements. However, they can influence decisions about where measurements should be made.

In the past measurements for fixed access have typically been system readings while measurements for mobile access have often been drive and walk tests, but crowdsourcing now provides an alternative to them. These techniques for QoS assessment in mobile networks are discussed in ITU-T Recommendation E.806 (ITU-T 2019b). It provides guidelines on the choice between active and passive measurements, the measurement of particular parameters, the characteristics of monitoring systems (except for crowdsourcing), data processing, and sampling. It is complemented by ITU-T Recommendation E.812 (ITU-T 2020a). That recommendation includes further advice on several of these topics (and on the characteristics of test servers for crowdsourcing).[7]

Auditing measurements

When different operators make measurements at different times and places, the results are not strictly comparable with one another. The costs can be reduced, and comparability can be achieved, by making measurements for all of the operators at the same time. However, operators might not be prepared to have their own drive and walk tests done by a common agent. In these circumstances, the results need to be checked by the regulator.

To this end, each operator should hold records of its measurements for perhaps a year after they have been made. The records should include details of the observations and calculations, and any fault reports or service complaints, on which the measurement results depended. They would be provided to the regulator to be compared against other measurements made by the regulator or other operators. The comparisons would determine whether:

- The measurement results were likely to be valid.

- The measurements needed more precise definitions because different operators interpreted them differently.

If the operators use crowdsourcing, they might have different data collectors to collect and process the data into measurement results. To check the extent to which the measurement results for different operators are comparable, the regulator would examine in detail the data collection and processing done for each operator and would ask for changes if necessary.

In crowdsourcing, each individual user is testing only one network at a time. However, there can be so many users that there are enough tests of each service. If extra tests are wanted, the regulator can arrange that calls are set up on multiple smartphones (one for each network) at particular times and places.

Even if crowdsourcing is not the main QoS measurement method, it can be useful in auditing, when the measurement results stated by the operators can be compared with ones obtained by crowdsourcing.

Publishing measurements

Publishing QoS information is important if customers are to make informed choices. Publication can be by the regulator or the operators. It is most cheaply and consistently done by one organization; moreover, the regulator is better placed than the operators to offer impartial comparative figures side-by-side. However, often the operators have more resources than the regulator, so they need to publish their own QoS information as approved by the regulator, in formats agreed by the regulator.

In providing information to users, a balance must be struck: users should not be overloaded but should have enough information on which to base their decisions. In particular:

- Measurement results could be displayed in rankings, tables, bar charts, or star charts (possibly with “traffic light” colours or other marks to indicate whether the measurement results were “good enough”).[8] They might be accompanied by explanations by the operators or by the regulator of the causes of any unsatisfactory measurement values.

- Measurement results should use the same numerical conventions as each other, as far as possible. Thus, in all, or almost all, cases either a high value or a low value should indicate good quality; for instance, alongside the dropped call ratio would be the unsuccessful call set-up ratio, not the successful call set-up ratio. As users find small numbers easier to assess than large numbers, low values should probably indicate good quality, at least for parameters that are percentages. However, mean opinion score (MOS) treats high values as good.

- Measurement results should be written with at most two significant figures. Further figures would rarely express distinctions in quality that users would appreciate.

- Measurement results could be presented in layers, with each layer providing pointers to a more detailed layer. Users are likely to be interested in particular parts of the QoS information, not all of it; for instance, one might be interested in speech quality on main roads, while another was interested in broadband availability in remote places.[9] Different presentations, with different levels of detail, are needed by different people. For instance, policy makers, opinion formers, service providers, and large businesses might want web pages and newspaper statements, but private consumers and small businesses will prefer leaflets, bill inserts, social media feeds, radio and television advertisements, freephone messages, and community meetings.

- Measurement results should be presented fairly. For instance, results for an operator that needs to use the network of another operator might be annotated with explanations if they are worsened by deficiencies of that network.

Stimulating improvements

If improvements in quality are needed, then investments might be needed and imposing fines could be counter-productive, as noted in ITU Recommendation E.805 (ITU-T 2019a). For instance, the regulator in Chad, having noted that the fines imposed over several years had had no effect, replaced fines with requirements to invest amounts equivalent to the fines in improving the networks within six months (ARCEP 2020).

Devising and implementing plans to stimulate improvements can help the operators and the regulator to work together in the associated task of developing and modifying the parameters and targets so that they stay suitable. Giving users information that compares operators allows competition to be a spur to improvement, especially if changing operators is easy.

Both good and bad publicity can act as ways of stimulating improvement. For instance, operators that perform far better than the others (or than the targets require) could be publicized by the regulator and awarded titles such as “broadband operator of the year” (or at least of the review period). Currently few regulators do anything like this; indeed, many do not even name and shame the operators that are deficient or publish separate figures for separate operators.

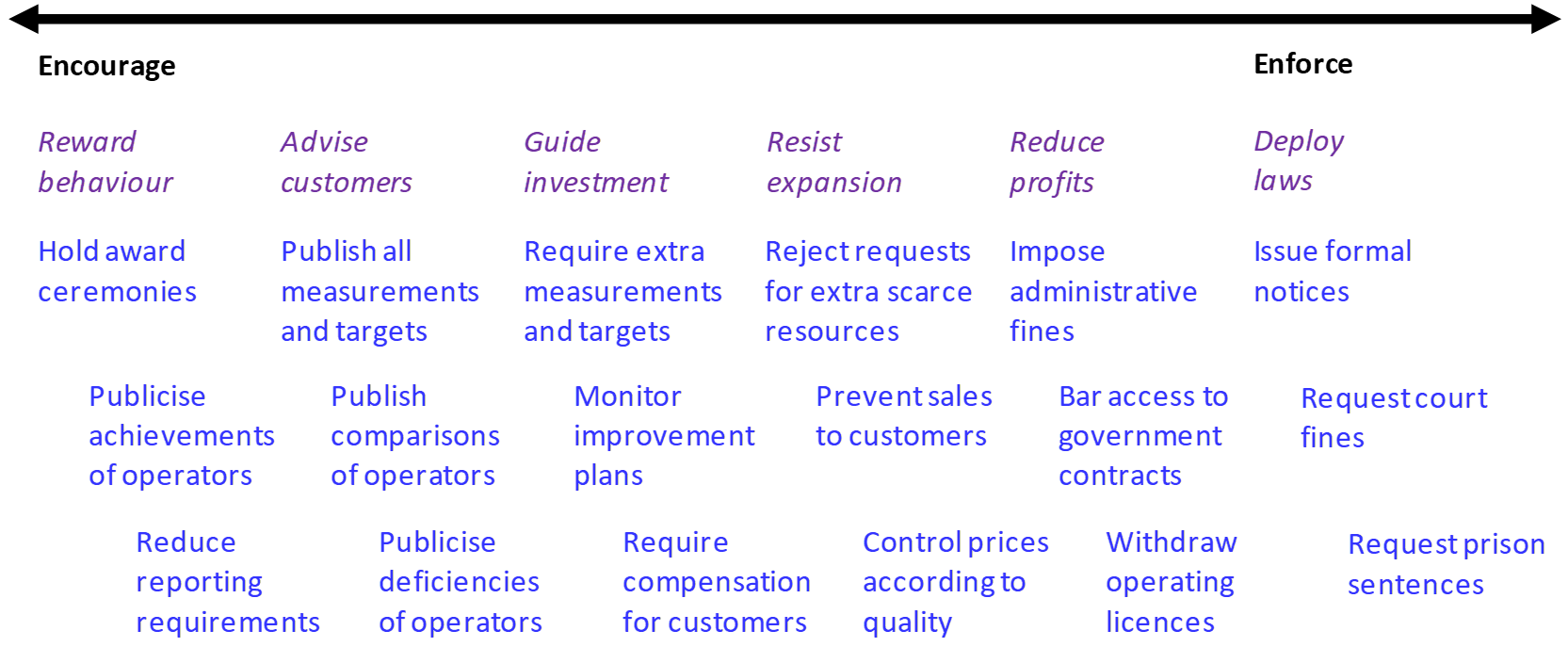

There is a wide range of techniques available to stimulate quality, as depicted in Figure 8.2.[10] Their applications should have reasoned justifications; otherwise ultimately the rule of law might be disregarded (by citizens or the government). They can be graduated to fit how far operators are trying to improve quality without raising prices. They should also be proportionate and responsive, as discussed in ITU-T Recommendation E.805 (ITU-T 2019a). For instance, penalties should be related to the persistence and severity of failures to comply with regulations and licences.

Figure 8.2. Techniques for stimulating improvements in quality

Source: Adapted from ITU-D 2006.

The costs of QoS measurements bear most heavily on small operators, because the number of measurements needed for precise enough results is independent of the size of the operator. There is, therefore, a case for exempting operators from making QoS measurements for regulators in places where their customers form small proportions of the population (less than 5 per cent, for example), as in Brazil (Anatel 2020). Nonetheless, they might choose to make these measurements, because of the beneficial publicity that good test results can provide, especially if they are intent on building their market shares.

If small operators are not exempted from making QoS measurements for the regulator, they might still be exempted from full enforcement. In particular, they might be exempted from being fined, even when they are not exempted from being required to implement improvement plans. This is in keeping with the view that enforcement should be proportionate and responsive, as discussed in ITU-T Recommendation E.805 (ITU-T 2019a).

Reviewing achievements

In reviewing QoS monitoring against its purposes, changes during the review period in the market environment, as well as those in QoS, are relevant. For instance:

- Parameters can be discarded if they are no longer important.

- Targets, and exemptions from QoS monitoring for small operators, can be discarded if competition has grown strong enough.

- Crowdsourcing might play a greater role in QoS monitoring if smartphones have become widely available.

- Reporting periods might be lengthened if improving on good results takes longer than improving on bad ones.

The QoS monitoring framework tends to be difficult to change if it is stated in licences that need to be negotiated with several operators or in regulations that need to pass through several government bodies before coming into effect. Such processes can sometimes be avoided for QoS monitoring requirements that are consistent with government policy and not controversial; for instance, the requirements might be stated in schedules or open letters to operators. However, avoiding such processes generally limits the powers of the regulator: some ways of encouraging improvements in QoS lose their legal foundations, so persuasion needs to replace compulsion.

Notes

- Both shortcomings are illustrated in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The ECTEL experience of quality of service regulation”. ↑

- The appropriate sorts of assessment are described in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The relation between quality of service and quality of experience”. ↑

- Hence eight out of fourteen entries are struck through in the table in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The Anatel approach to quality of service monitoring for mobile services”. ↑

- The relation between confidence levels and sample sizes is explained in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Basic statistics for quality of service assessment”. Another account, concentrating on how to score and rank operators against each other, can be found in ITU-T Recommendation E.840 (ITU-T 2018). ↑

- Descriptions of means and quantiles are given in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Basic statistics for quality of service assessment”. Further descriptions, accompanied by details about several useful distributions, can be found in an ETSI technical specification (ETSI 2019). ↑

- The purposes of subjective and objective assessments of quality are discussed in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The relation between quality of service and quality of experience”. ↑

- A related discussion can be found in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Crowdsourcing techniques in quality of service assessment”. ↑

- Most of these possibilities are illustrated in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Examples of quality of service presentation by regulators”. ↑

- The range of information provided in Brazil is shown in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The Anatel approach to quality of service monitoring for mobile services”. ↑

- Several of these techniques are mentioned in the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Examples of quality of service presentation by regulators”. ↑

References

Anatel. 2020. Qualidade – Telefonia Móvel. https://www.anatel.gov.br/dados/controle-de-qualidade/controle-telefonia-movel.

ARCEP. 2020. Évaluation QoS et QoE et analyse comparative des réseaux mobiles au Tchad. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/Workshops-and-Seminars/qos/202003/Documents/1.%20QoS%20and%20QoE%20assessment%20and%20comparative%20analysis%20of%20mobile%20networks%20in%20Chad.pdf.

CICRA. 2019. Telecoms Customer Satisfaction in the Channel Islands 2018. https://www.gcra.gg/media/597877/t1370gj-telecoms-customer-satisfaction-report.pdf.

EACO. 2017. EACO Guidelines on Consumer Experience and Protection in Digital Financial Services. http://www.eaco.int/admin/docs/publications/GUIDELINE%20FOR%20CONSUMER%20QoE.pdf.

ETSI. 2019. Speech and Multimedia Transmission Quality (STQ); QoS Aspects for Popular Services in Mobile Networks; Part 6: Post Processing and Statistical Methods. ETSI TS 102 250-6 V1.3.1 (2019-11). https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/102200_102299/10225006/01.03.01_60/ts_10225006v010301p.pdf.

Fratel. 2019. Mesurer la performance des réseaux mobiles: couverture, qualité de service et cartes. https://www.fratel.org/documents/2019/10/Document-Fratel-couverture-et-qualité-de-service-mobiles.pdf. See the dedicated website: https://www.donneesmobiles.fratel.org/?lang=en

Fratel. 2020. Measuring Mobile Network Performance: Coverage, Quality of Service and Maps. https://www.fratel.org/documents/2020/05/document-Fratel-ENG-web.pdf. See the dedicated website: https://www.donneesmobiles.fratel.org/?lang=en

ITU-D. 2006. ICT Quality of Service Regulation: Practices and Proposals. https://www.itu.int/ITU-D/treg/Events/Seminars/2006/QoS-consumer/documents/QOS_Bkgpaper.pdf.

ITU-D. 2017. Quality of service regulation manual.

ITU-T. 2007. Framework and Methodologies for the Determination and Application of QoS Parameters. ITU-T Recommendation E.802. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.802-200702-I.

ITU-T. 2011. Quality of Service Parameters for Supporting Service Aspects. ITU-T Recommendation E.803. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.803/en.

ITU-T. 2013b. Supplement 9 to ITU-T E.800-series Recommendations (Guidelines on Regulatory Aspects of QoS). ITU-T Recommendations Series E.800 Supplement 9. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.800SerSup9/en.

ITU-T. 2017. Vocabulary for Performance, Quality of Service and Quality of Experience. ITU-T Recommendation P.10/G.100. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-P.10/en.

ITU-T. 2018. Statistical Framework for End-to-End Network Performance Benchmark Scoring and Ranking. ITU-T Recommendation E.840. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.840/en.

ITU-T. 2019a. Strategies to Establish Quality Regulatory Frameworks. ITU-T Recommendation E.805. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.805/en.

ITU-T. 2019b. Measurement Campaigns, Monitoring Systems and Sampling Methodologies to Monitor the Quality of Service in Mobile Networks. ITU-T Recommendation E.806. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.806/en.

ITU-T. 2020a. Crowdsourcing Approach for the Assessment of End-to-End QoS in Fixed and Mobile Broadband Networks. ITU-T Recommendation E.812. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.812/en.

ITU-T. 2020b. Video Quality Assessment of Streaming Services over Reliable Transport for Resolutions up to 4K. ITU-T Recommendation P.1204. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-P.1204/en.

ITU-T. 2020c. Methodology for QoE Testing of Digital Financial Services. ITU-T Recommendation P.1502. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-P.1502/en.

Marina, M.K., V. Radu, and K. Balampekos. 2015. “Impact of Indoor-Outdoor Context on Crowdsourcing based Mobile Coverage Analysis”. AllThingsCellular ’15: Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on All Things Cellular: Operations, Applications and Challenges, August 2015: 45-50. http://doi.org/10.1145/2785971.2785976.

Ofcom. 2016. Digital Day 2016: Media and Communications Diary: Aged 6+ in the UK. http://www.digitaldayresearch.co.uk/media/1086/aged-6plus-in-the-uk.pdf.

Ofcom. 2019. Comparing Service Quality Research 2018: Reasons to Complain. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/145819/reason-to-complain-research-2018-chart-pack.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022