Transformative technologies (AI) challenges and principles of regulation

08.05.2024Introduction

We are witnessing a remarkable transformation that is rapidly shaping the world as we know it. The pace of this change is exponential, driven by a wave of innovative technological trends that are changing how we live, work, and communicate. From the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to the proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT), Blockchain, robotics, 3D printing, nanotechnology, augmented and virtual reality, these cutting-edge technologies are converging to usher us into a new digital era. This revolution is transforming every aspect of our lives, from how we conduct business to how we interact with one another, and is poised to have far-reaching implications for the future of humanity.

This new digital era is different due to the extensiveness of its scope and the vitality of its impact on human interaction and identity, distribution, production, and consumption systems around the globe. It is pervasive and non-linear; often, its consequences cannot be anticipated with certainty. It is an era where machines learn on their own; self-driving cars communicate with smart transportation infrastructure; smart devices and algorithms respond to and predict human needs and wants.

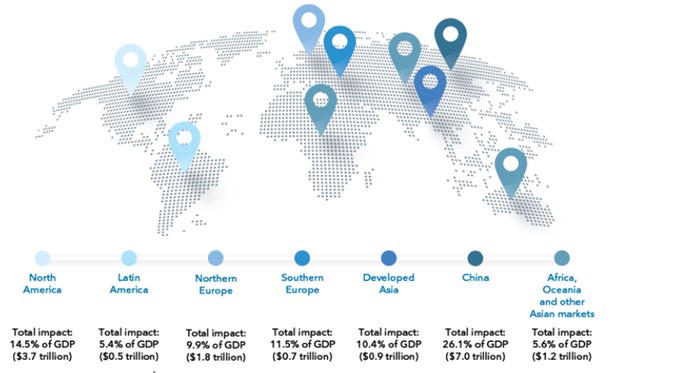

To illustrate this, Al-powered products and services have the potential to lead to new medicines, speed the transition to a low-carbon economy, and help people enjoy dignity in retirement and old age. The economic gains alone could be enormous. AI could contribute up to USD 15.7 trillion to the global economy by 2030, more than the current output of China and India combined. Of this, USD 6.6 trillion will be derived from increased productivity, and USD 9.1 trillion will be derived from consumption-side effects. The projected impact for Africa, Oceania, and other Asian markets is USD 1.2 trillion. For comparison, the combined 2019 GDP for all the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa was USD 1.8 trillion. Thus, successfully deploying AI and big data presents a world of opportunities.[1]

Figure 1. Expected economic gains from AI in different regions of the world

Source: ITU Emerging technology trends: Artificial intelligence and big data for development 4.0 report, 2021[2].

New governance frameworks, protocols, and policy systems are needed for the new digital era to ensure all-inclusive and equitable benefits. Societies need regulatory approaches that are not only human-led and human-centred but also nature-led and nature-centred. Government policies need to balance public interests, such as human dignity and identity, trust, nature preservation and climate change, and private sector interests, such as business disruptiveness and profits. As novel business models emerge, such as fintech[3] and the sharing economy[4], regulators are faced with a host of challenges: rethinking traditional regulatory models, coordination problems, regulatory silos, and the robustness of outdated rules.

This reinforces the need to build flexible and dynamic regulatory models to respond to the changes and optimise their impact. A complex web of regulations would impose prohibitive costs on new entrants into transformative technologies’ markets. Imposing cumbersome compliance costs with a robust system of regulations would lead to a situation where only large firms could afford to comply.

This article highlights the unique regulatory issues posed by transformative technologies: the unpredictable nature of business models that rely on transformative technologies, the importance of data ownership, control, privacy, consumer protection, and security, and the AI conundrum. The article further defines and provides a set of principles to guide the future of regulation of transformative technologies: innovative and adaptive regulation, outcome-focused regulation, evidence-based regulation, and collaborative regulation.

Transformative technologies regulation: the challenges

Traditional regulatory structures are complex, fragmented, risk-averse, and adjust slowly to shifting social circumstances, with various public agencies having overlapping authority. On the other hand, a unicorn startup can develop into a company with a global reach in a couple of years, if not months. For instance, Airbnb went from a startup in 2008 to a Silicon Valley unicorn in 2011, valued at a billion dollars, based on USD112 million invested by venture capitalists.[5]

Transformative technologies are multifaceted and transcend national boundaries. Since there are no global regulatory standards, coordinating with regulators across borders is a challenge.

There are three key challenges in regulating transformative technologies: (i) the unpredictable nature of business models that rely on transformative technologies, (ii) data privacy, security, ownership, and control, and (iii) the AI conundrum.

The unpredictable nature of business models that rely on transformative technologies

Products and services embedded in transformative technologies’ solutions evolve quickly and shift from one regulatory category to another. For example, if a ride-hailing company, such as Uber, begins delivering food, it can fall under the jurisdiction of health regulators. If it expands into delivering drone services, it will fall under the purview of aviation regulators. If it uses self-driving cars for passengers, it may come under the jurisdiction of the transport regulators. Maintaining consistency in regulations is difficult in the sharing economy, where the lines between categories and classifications of services and products are often blurred.

Recently, Airbnb won a court battle in the European Union (EU) that affected how the company would be regulated in the future. The EU’s Court of Justice has ruled that Airbnb should not be considered an estate agent but an “information society service,” meaning it can avoid specific responsibilities and continue operating as an e-commerce platform.[6]

However, in the case of Uber, the EU Court of Justice ruled that the company is a transportation service and not a platform. The Court ruled that the difference between Uber and Airbnb is in the level of control exercised by Airbnb over the services hosted on its platform. Unlike Uber, which has controlled pricing and automatically paired up sellers and customers, Airbnb has allowed property owners to set their own prices and rent their homes using other channels.[7]

Transformative technologies and liability

The fast-evolving, interconnected nature of disruptive business models can also make assigning liability for the harm done difficult. For example, if a self-driving car crashes and kills someone, who will be held liable — the system’s programmers, the driver behind the wheel, the car’s manufacturer, or the manufacturer of the vehicle’s onboard sensory equipment? The general inclination across different jurisdictions has been towards assigning strict liability for the damage caused by transformative technologies under certain circumstances, such as using these technologies in public spaces (e.g., drones and self-driving cars).[8]

The legal concept of liability is challenged even more by the concept of reinforcement learning, a training method that allows AI to learn from past experiences. Imagine a scenario where an AI-controlled traffic light learns that changing the light one second earlier is more efficient, resulting in more drivers running the light and causing more accidents. In this example, human control is removed several times, making it difficult for regulators to assign liability.[9]

3D printing is another transformative technology that challenges the traditional legal concept of liability. If a 3D house crashes down, who is to blame — the supplier who supplied the design, the manufacturer who 3D printed the house parts or the manufacturer of the 3D printer?

Blockchain and its decentralised nature present a different type of concern to regulators. Even though blockchain applications have been praised for their security and immutability, their anonymous and decentralised nature is a novel challenge for regulators around the globe. An illustrative example in this regard is the cyberattack of the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO), a decentralised investment fund running on Ethereum, a blockchain platform. DAO’s creators intended to build a democratic financial institution whose code would eliminate the need for human control and oversight. However, in 2016, a hacker took advantage of a flaw in DAO’s code and stole USD50 million of virtual currency. The hacker has not been identified yet, and due to the decentralised nature of the system, liability cannot be assigned to anyone or anything.[10]

The importance of data: ownership, control, privacy, consumer protection and security

The rising use of smartphones, security cameras, connected devices, and sensors has created a massive digital footprint and data overload. An illustration of data overload can be seen in the case of self-driving cars, which are expected to churn out around 4,000 gigabytes of data per day.[11] Other machines generating data overload include satellites, environmental sensors, security cameras, and mobile phones. [12]

People’s lives can benefit greatly when decisions are informed by pertinent data that reveal hidden and unexpected connections and market trends. For instance, identifying and tracking genes associated with certain types of cancer can help inform and improve treatments. However, often unaware, ordinary people bear many of the costs and risks of participating in data markets. In many jurisdictions, the so-called data brokers are amassing and selling personal data, which is a legal practice.[13]

The data economy brings along disruptive changes propelled by AI and machine learning. For instance, AI and big data are already replacing human bankers. Many fintech lending startups have started using alternative data sources, and traditional insurance companies are following suit. Regulators are struggling to provide guidelines in this area that would enable the financial industry to innovate and, at the same time, protect consumers from bias and discrimination. For example, New York’s Department of Financial Services has released new guidelines that allow life insurance companies to use customers’ social media data to determine their premiums (as long as they do not discriminate).[14]

Data ownership

From a regulatory point of view, the crux of the question is who has access and control over all this data. Is it the government, the users, or the service providers who store the data? From a legal perspective, data per se cannot be owned, and no legal system offers ownership of raw data.[15] If the service provider has access to personal information, what obligation does it have to store and protect it? Can the service provider share our personal data with third parties, i.e., data brokers? Can a car manufacturer charge a higher price to car buyers who refuse to share their personal data?[16]

Usage of data

Privacy impacts data use far beyond consumers’ understanding. Consumers may sign up for a clever app, not realising that the app is using account data for purposes far broader than necessary for immediate use. Or they may apply for a loan, thinking that account access is just for the primary purpose of granting the loan without realising that the company has ongoing access to their account. These issues become compounded.

Data sharing and sale

Privacy policies can often be challenging to understand and may seem vague or unclear to consumers. As a result, people may not always be aware of how businesses collect, use, and share their personal information. Sometimes, this can lead to their data being sold or shared with third parties without their knowledge or consent. This issue is further exacerbated by the increasing use of automated systems and algorithms in data processing, which can make it even more challenging for individuals to keep track of how their data is being handled.[17]

No global agreement on data protection

There is no global agreement on data protection, and regulators around the globe take very different, oftentimes conflicting, stances in regulating data within their national borders. For instance, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides for the principle of privacy, strict controls over cross-border data transmissions, and the right “to be forgotten”. The GDPR will likely influence other countries to revise their data protection legislation. The GDPR already has an extraterritorial grasp on the private sector’s data transactions across borders. Global companies are revising privacy policies to comply with the GDPR. Content websites outside Europe have already started denying access to European consumers because they could not ensure compliance with the GDPR.[18]

Unlike the EU approach, the US approach has been more segmented and focused on sector-specific rules (e.g., health care, financial, and retail) and state laws. In the US, it is not unusual for credit card companies to know what their customers consume. For instance, Uber knows where its customers go and how they behave while taking the drive. Social media platforms know if their users like to read CNN or Breitbart News.

In the EU, the right to privacy and the right to have personal data protected are fundamental rights guaranteed by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.[19] The EU has an umbrella data protection framework that does not differentiate between data held by private or public actors, with only a few exceptions (e.g., national security). By contrast, in the US, for example, the right to privacy is not considered a fundamental right. The right to privacy is counter-balanced by strong rights to free speech and freedom of information. Nevertheless, some cities and states have started regulating privacy following the EU’s GDPR model.[20]

Anonymisation does not equal privacy

The privacy of public data is usually protected through anonymisation. Identifiable things such as names, phone numbers, and email addresses are stripped out. Data sets are altered to be less precise, and “noise” is introduced to the data. However, a recent study by Nature Communications suggests that anonymisation does not always equate to privacy. Researchers have developed a machine-learning model that estimates how individuals can be re-identified from an anonymised data set by entering their zip code, gender, and date of birth. [21]

Cybersecurity is a key regulatory challenge in the era of transformative technologies

Cybersecurity is particularly important in areas such as fintech, digital health, digital infrastructure, and intelligent transportation systems, where private, sensitive data can be compromised. Take, for instance, the case of self-driving cars that need to communicate with the transport infrastructure. Designers and manufacturers of self-driving cars should take necessary precautions to ensure that the system is not overtaken by hackers who might try to steer the vehicle into causing accidents. Hackers might also try to manipulate traffic lights to disrupt traffic.[22]

Another example is data aggregators that access a host of sensitive personal and financial information and provide much of that information to third parties. It is difficult for consumers to know whether the data aggregator or the end user fintech has robust security controls. Data breaches are common even at the largest companies with extensive compliance programs. Small fintech startups may be especially vulnerable.

Data aggregators and fintech companies often require consumers to turn over their bank account and login credentials to engage in “screen scraping” of account records, which increases security risks. Though data aggregators have struck agreements with many banks to use more secure application programming interfaces (APIs), screen scraping is still used to access accounts at smaller institutions.[23]

Generative AI presents new risks and challenges that need to be managed with robust security practices and ethical guidelines. For example, it can be used to create sophisticated phishing attacks by generating realistic-looking emails, messages, or websites designed to deceive users into divulging sensitive information. The ability of AI to understand context and mimic human communication styles can make these attacks particularly effective. Generative AI can also create audio and video deepfakes that are increasingly difficult to distinguish from genuine media. This capability can be exploited to spread disinformation, manipulate public opinion, or impersonate individuals for fraudulent purposes, posing significant challenges to cybersecurity and information integrity.[24]

IoT, data protection and cybersecurity

The IoT is omnipresent nowadays. One study estimated that there would be 50 billion active IoT devices worldwide by 2022.[25] And that’s counting offers only for consumers, not “smart” offices, buildings, and factories. For example, it was estimated that there will be an average of 14.8 appliances and devices connected to the Internet in EU households by 2022 – light switches, lights, heating controls, security cameras, blinds, doorbells, loudspeakers, etc. [26]

The example of smart wearables. Smart wearables provide new solutions to healthcare through medical monitoring, emergency management and safety at work. These electronic devices can monitor, collect, and record biometric, location and movement data in real time and communicate this data via wireless or cellular communications.

In 2018, 2 million employees with dangerous or physically demanding roles (e.g., paramedics and firefighters) were required to wear health and fitness tracking devices as a condition of their employment.[27] More than 75 million wearables were used in the workplace by 2020. Employers recognise that supporting the health of their staff translates into reduced healthcare costs, less sick leave taken, and higher productivity.[28]

Smart wearables raise interesting data privacy questions: are the companies that monitor health-related data under an obligation to disclose that data to the subjects they belong to if, for example, the device reveals certain health conditions? To what extent can companies use this data for secondary purposes?[29]

The example of smart home devices. Ubiquitous smart home devices present another challenge to regulators. Challenging questions for regulators in this regard are the following: what is the extent to which the manufacturer of one smart device may be to blame for the failure of another smart device? If, for example, a smart fridge can be hacked and bypassed to unlock a connected smart lock, to what extent should liability for the economic loss of items stolen from the home be distributed between the manufacturers of each product? Depending on how these issues are tackled, there may potentially be a significant risk, as a single weakness in the code could be applied to thousands of products written with the same code.[30]

Given that IoT devices tend to process personal data, many of the data processing activities involved in IoT operations will fall within personal data protection regulations. To ensure compliance with stringent data protection regulations, the design of the IoT product should incorporate concepts of transparency, fairness, purpose limitation, data minimisation, data accuracy, and the ability to deliver on data subject rights.

Determining if certain stakeholders act as data controllers or data processors in a particular processing activity in the IoT data protection context can also be challenging. For example, device manufacturers qualify as controllers for the personal data generated by the device as they design the operating system or determine the overall functionality of the installed software. Third-party app developers that organise interfaces to allow individuals to access the data stored by the device manufacturer can be considered controllers. Other third parties (e.g., an insurance company offering lower fees by processing data collected by a step counter) can be considered controllers when IoT devices collect and process information about individuals. These third parties usually use the data collected through the device for other purposes different from the device manufacturer.[31]

IoT stakeholders need to conduct an assessment over the processing activities to identify the respective data protection roles (e.g., controller, joint controllers or processor) and correctly allocate responsibilities (particularly about transparency and data breach obligations and data subject rights).

AI and machine learning might lead to power imbalances and information asymmetries for consumers

AI-based applications raise new, so far unresolved legal questions, and consumer law is no exception.

Targeted advertising

Using self-learning algorithms in big data analytics gives private companies an opportunity to gain a detailed insight into one’s personal circumstances, behaviour patterns and personality (purchases, sites visited, likes on social networks, health data). AI is used in online tracking and profiling of individuals whose browsing habits are collected by “cookies” and digital fingerprinting and then combined with queries through search engines or virtual assistants. Companies can tailor their advertising, prices, and contract terms to the respective customer profile and – drawing on the findings of behavioural economics – exploit the consumer’s biases and/or her willingness to pay. AI-based insights can also be used for scoring systems to decide whether a specific consumer can purchase a product or take up a service.

This creates growing issues for privacy and data protection. Targeted advertising uses internet tracking and profiling based on the person’s expected interests. The use of all these methods has incapacitated users from giving meaningful consent because everything is automated. Intensive data processing using AI may exacerbate other rights violations when personal data is used to target individuals, such as in the context of insurance or employment applications, or when algorithms threaten both the right to privacy and the freedom of expression. For instance, social media algorithms decide the content of a user’s newsfeed and influence the number of people who see and share information. Search engine algorithms index content and determine what appears at the top of search results, raising concerns about diversity of views.

Price discrimination

AI supports digital businesses in presenting consumers with individualised prices and offering each consumer an approximation of the highest price point that the consumer may be able or willing to pay. Certain markets, such as credit or insurance, operate on cost structures based on risk profiles correlated with features distinctive to individual consumers, suggesting that it may be reasonable to offer different prices (e.g., interest rates) to different consumers. Should regulators allow price discrimination in other cases, too, based on the ability of different consumers to pay?[32]

Consumers are not usually aware that advertising, information, prices, or contract terms have been personalised according to their profile. Suppose a particular contract is not concluded or only offered at unfavourable conditions because of a certain score calculated by an algorithm. In that case, consumers often cannot understand how this score was achieved. The complexity, unpredictability, and semi-autonomous behaviour of AI systems can also make effective enforcement of consumer legislation difficult, as the decision cannot be traced to a singular actor and, therefore, cannot be checked for legal compliance.

Deep Dive on Transformative Technologies’ Regulation: Regulating AI

In the past two years, numerous countries have begun to establish robust governance frameworks for AI. The European Union has been a frontrunner in this area with its AI Act, and countries such as the United States, Canada, China, and the United Kingdom have followed suit. This trend stems from adopting risk-based approaches to AI regulation, where authorities aim to manage AI applications based on their potential risks to societal and human well-being. The Stanford AI Index has revealed that there has been a significant increase in the number of bills containing the term “artificial intelligence” that have been passed into law. In 2016, only one such bill was passed, but this number has grown to 37 by 2022. Moreover, a comprehensive analysis of parliamentary records on AI in 81 countries indicates that mentions of AI in global legislative proceedings have increased nearly 6.5 times since 2016.[33]

Spotlight on Generative AI systems

We are currently experiencing an unprecedented era of progress in generative AI, which refers to machine learning algorithms that can create new content like audio, code, images, text, simulations, and videos. These algorithms have recently gained attention for their ability to power chatbots such as ChatGPT, Bard, and Copilot, which use large language models (LLMs) to perform various functions, including research gathering, legal case file compilation, repetitive clerical task automation, and online search. The technology has the potential to dramatically increase efficiency and productivity by simplifying specific processes and decisions, such as streamlining physician medical note processing or helping educators teach critical thinking skills.[34]

Natural language generation is a popular application of generative AI, with ChatGPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), garnering a lot of attention lately. The hype surrounding text-based generative AI often revolves around a model called GPT, short for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. Pre-training a language model and fine-tuning it on a specific dataset is not a new concept, as it has been utilised in other models for decades. However, GPT is notable for its use of transformer architecture on a large scale, which allows it to generate human-like texts. This has made GPT a popular choice in natural language processing. For instance, ChatGPT is a chatbot that leverages advanced NLP and reinforcement learning to participate in realistic discussions with people. ChatGPT can generate articles, tales, poetry, and even computer code. It can also respond to questions, engage in discussions, and, in certain instances, provide extensive replies to extremely precise questions and inquiries. ChatGPT was released in November 2022 and acquired over one million users within a week.

However, the ongoing advancements and applications of generative AI have sparked important questions regarding its impact on the job market, its use of training data that can be protected by privacy and copyright rules, and the necessary government regulations.

Many governments around the globe have started curtailing the use of generative AI. Due to data protection and privacy concerns, the Italian data protection regulator, the Garante, issued a temporary ban on ChatGPT, which was removed after OpenAI started cooperating with the Garnte, including by publishing a new information processing notice, expanding its privacy policy and offering users an opt-out from data processing.[35] The Canadian Government has released a draft of a code of practice for Generative AI, which is open for public comment before being enacted into law as part of the country’s Artificial Intelligence and Data Act.[36] The G7 launched the Hiroshima AI Process to coordinate discussions on generative AI risks.[37] In July 2023, US President Joe Biden announced voluntary commitments from large AI companies to support safety, security, and trust.[38] On July 13, 2023, China implemented temporary measures to regulate the generative AI industry. Service providers are now required to undergo security assessments and file algorithms.[39] The Beijing Municipal Health Authority proposed 41 new rules that would strictly prohibit the use of AI in various online healthcare activities, including automatically generating medical prescriptions.[40] The United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has launched a wide-ranging investigation into OpenAI. The probe is focused on allegations that OpenAI has violated consumer protection laws by putting personal data and reputations at risk.[41] The FTC’s Civil Investigative Demand has raised concerns that ChatGPT may produce false or disparaging statements about real individuals. The agency has also requested information following a data privacy breach in which private user data was exposed in ChatGPT’s results.[42] Under the European Union’s AI Act, those who develop general-purpose AI models will have to comply with the EU copyright laws and provide a detailed summary of the data, including text, pictures, and videos used to train the systems. AI-generated deepfake pictures, videos, or audio based on existing people, places, or events must be labelled as artificially manipulated. The Act requires that the more powerful AI models, which pose “systemic risks” like OpenAI’s GPT4 and Google’s Gemini, undergo extra scrutiny. The EU is concerned that these advanced AI systems could cause accidents or be used for cyberattacks, and about potential biases that could be spread across many applications and affect many people.[43]

European Union (EU): The AI Act

The EU has been at the forefront of regulatory frameworks for AI. In 2019, following the publication of the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, the European Commission started a three-pronged approach to regulating AI and addressing AI-related risks. In addition to the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act)[44], the new and amended civil liability rules[45] act in conjunction with other current and planned data-related policies, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Services Act, the Data Act[46], and the Cyber Resilience Act.[47]

As of early 2024, the most significant development is the progression of the AI Act, initially proposed in April 2021. This legislation aims to address the risks associated with specific uses of AI and establish a legal framework for ensuring AI across the EU is safe and lawful and respects existing laws on fundamental rights and values.

Key aspects of the AI Act include:

- Risk-based Approach: The AI Act categorises AI systems according to the risk they pose to safety and fundamental rights. Systems are classified into four risk categories—from minimal to unacceptable risk—with corresponding regulatory requirements.

- High-Risk AI Systems: Stringent requirements are proposed for high-risk applications, such as those in critical infrastructures, employment, and essential private and public services. These include risk assessment and mitigation, high-quality data sets to train AI systems, detailed documentation to trace datasets and algorithms, transparency measures, and human oversight.

- Bans and Restrictions: The AI Act proposes outright bans on AI practices deemed to be clear threats to people’s safety, livelihoods, and rights. This includes AI systems or applications that manipulate human behaviour to circumvent users’ free will (e.g., toys using voice assistance encouraging dangerous behaviour in children) and systems that allow ‘social scoring’ by governments.

- Governance and Enforcement: The AI Act outlines enforcement mechanisms, including national supervisory authorities responsible for its enforcement and a European Artificial Intelligence Board for oversight. It also proposes fines for non-compliance, which can be up to 6% of global annual turnover.

- Innovation-friendly Ecosystem: The regulation is designed to foster an ecosystem of trust that could potentially enhance investment and innovation in AI within the EU.

As the AI Act is still being negotiated by EU institutions, its final form may evolve. Its broad implications affect AI development and deployment within the EU and for global companies operating in the region. The legislative process has involved extensive discussions and amendments, reflecting the complexity of regulating such a dynamic and impactful technology. The EU’s approach could serve as a blueprint for AI regulation globally, emphasising the balance between innovation and safeguarding societal values.

The EU AI Act sets horizontal standards for developing, commercialising, and using AI-powered products, services, and systems within the EU. It provides fundamental AI risk-based guidelines applicable across all industries and includes a “product safety framework” with four risk categories. The framework specifies market entry rules and certification for High-Risk AI Systems through a mandatory CE-marking process. This compliance regime also covers datasets used for machine learning training, testing, and validation to ensure fair outcomes.

Categories of Risk

The AI Act categorises AI systems into four levels of risk: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk, and minimal risk.

- Unacceptable Risk: AI applications threatening safety, livelihoods, and rights are prohibited. This includes AI systems that deploy subliminal techniques or take advantage of the vulnerabilities of specific groups of persons due to their age or physical or mental disability in a manner that can materially distort an individual’s behaviour and cause harm.

- High Risk: AI systems in critical sectors such as healthcare, transportation, policing, and legal/judicial systems fall into this category. The use of AI in employment, worker management, and access to essential private services (like credit scoring) also warrants stringent oversight due to their significant implications on individual rights and societal norms.

- Limited Risk: AI applications that require specific transparency obligations fall under this category. An example includes chatbots, where users should be informed that they are interacting with an AI, allowing them to make informed choices about continuing the interaction.

- Minimal Risk: The regulations are lenient for AI applications with minimal or no risk. This category includes most AI-enabled video games and spam filters. The belief here is that most AI applications fall into this category and do not require extensive regulation.

Regulatory Requirements

The requirements imposed on AI systems are proportional to the level of risk they are classified under:

- For High-Risk AI systems, compliance obligations include ensuring the accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity of the AI system; extensive documentation that details every aspect of the AI system, from its development phase to deployment; high standards of data governance to ensure data privacy and quality; transparency measures to ensure users understand the AI system’s capabilities and limitations; and human oversight mechanisms to prevent or minimise risk.

- For Limited Risk AI systems, the requirements are less stringent but still aim to safeguard user autonomy and trust. For example, transparency is a key requirement—users should know they are dealing with an AI system.

- For Minimal Risk AI systems, the regulation offers maximum flexibility with minimal obligations, encouraging innovation while still ensuring a baseline level of trust and safety.

This risk-based approach ensures that AI systems with significant implications for rights and safety undergo rigorous scrutiny while lower-risk applications can be developed and deployed more easily. This framework not only protects individuals but also fosters a regulatory environment that promotes technological advancement and economic growth.

Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States and China, have developed distinct frameworks for regulating and governing AI.

United Kingdom. The government introduced its cross-sector plan for AI regulation on July 18, 2022, which features a “pro-innovation” framework supported by six main principles addressing AI’s key risks. These non-statutory principles apply to all UK sectors and are supplemented by ‘context-specific’ regulatory guidance and voluntary standards developed by UK regulators. This approach differs from the EU AI Act, which offers a more prescriptive, horizontal approach to AI regulation across industries. Instead, the United Kingdom is moving towards a light-touch, risk-based, context-specific approach focused on proportionality, with practical requirements determined by the industry and dependent on the AI system’s deployment context. In March 2023, the United Kingdom Department for Science, Innovation and Technology published a White Paper, “A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation,” for consultation.[48]

In February of 2024, the UK’s Government released its response to the White Paper consultation on regulating AI that took place in 2023. As expected, the government has taken a “pro-innovation” approach, with the Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology (DSIT) leading the charge. The framework that the UK Government has proposed is principles-based, non-statutory, and cross-sectoral. Its goal is to balance innovation and safety by utilising the existing technology-neutral regulatory framework to regulate AI. The UK Government acknowledges that, eventually, they will have to take legislative action, particularly with regard to general-purpose AI systems. However, they believe that doing so now would be premature. Instead, they think it is essential to better understand the risks and challenges of AI, the regulatory gaps, and the best way to address them. This approach is highly contrasting when compared to other jurisdictions, such as the EU and, to some extent, the US, which adopt more prescriptive legislative measures.[49]

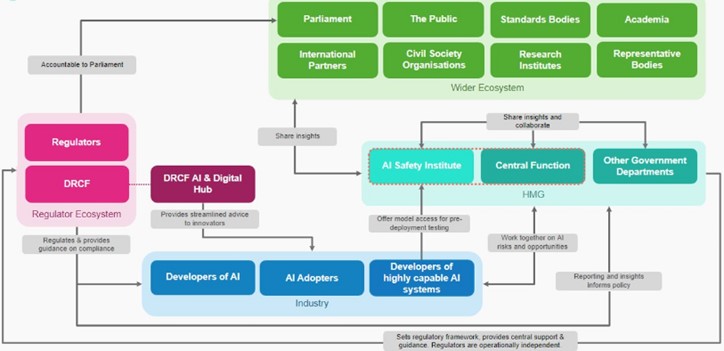

The UK has established a framework of five principles for existing regulators to apply to guide responsible AI design, development, and use across sectors.

The Government has established three main pillars for implementing its principles for AI regulation. These pillars include leveraging existing regulatory authorities and frameworks, establishing a central function to facilitate effective risk monitoring and regulatory coordination, and supporting innovation by piloting a multi-agency advisory service called the AI and Digital Hub. Unlike other countries, the UK has no plans to introduce a new AI regulator to oversee the implementation of the framework. Instead, existing regulators such as the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Ofcom, and the FCA have been asked to implement the five principles as they regulate and supervise AI within their respective domains. Regulators are expected to use a proportionate, context-based approach, utilising existing laws and regulations. The principles outlined for the regulation of AI implementation will not be legally binding. However, the Government has plans to introduce a legal duty for the regulators to consider these principles in their decision-making process. The timing of this duty will depend on the regulators’ strategic AI plans and a review of regulatory powers and responsibilities.[50] The Figure below gives an overview of the institutional set-up of AI governance in the UK.

AI governance landscape in the UK

AI regulation landscape. Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/ai-regulation-a-pro-innovation-approach-policy-proposals/outcome/a-pro-innovation-approach-to-ai-regulation-government-response#summary-of-consultation-evidence-and-government-response

Canada. The Directive on Automated Decision-Making requires most federal agencies to complete an Algorithmic Impact Assessment for any automated decision system (ADS) used to recommend or make administrative decisions about clients. As a result, through public-private collaboration, the Canadian government has initiated the development of a model Algorithmic Impact Assessment tool for agencies to reference or use in compliance with the Directive on Automated Decision-Making.[51] Moreover, the Directive is reviewed every six months to keep updated with new technological developments. This is an excellent example of an innovative and adaptive approach to AI governance.

United States. Congress passed the National AI Initiative Act in 2021, establishing the National AI Initiative as a framework for coordinating and strengthening AI research, development, demonstration, and education initiatives across all US Departments and Agencies. Several administrative agencies, including the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Department of Agriculture, Department of Defense, Department of Education, and Department of Health and Human Services, are involved in implementing a national AI strategy due to new offices and task forces established by the AI Act.

The Algorithmic Accountability Act of 2022, introduced in the US Congress in February 2022, is pending national legislation. This proposed act would direct the FTC to develop regulations requiring certain “covered entities” to conduct impact assessments before implementing automated decision-making processes, specifically covering AI and machine learning-based technologies. The FTC has started a regulatory process to address AI discrimination, fraud, and related data misuse, while other agencies have also initiated actions targeting AI practices.[52] This list of policy actions is beginning to resemble the EU’s position on “high-risk” AI.

The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) of the White House produced a Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights (Blueprint) in October 2022. This document offers a nonbinding roadmap for the appropriate use of AI. The Blueprint has outlined five fundamental principles to guide and govern the efficient development and implementation of AI systems, paying particular attention to the unintended consequences of civil and human rights violations. These principles are meant to guide and control the effective development and implementation of AI systems:

- Safe and effective systems: Users should be protected from unsafe or ineffective systems.

- Algorithmic discrimination protections: users should not be exposed to discrimination by algorithms; automated decision-making systems should be used and designed equitably.

- Data privacy: users should be protected from abusive data practices via built-in protections and have agency over how their data is used.

- Notice and explanation: users must be informed that an automated system is being used and understand how and why it contributes to outcomes that impact them.

- Alternative options: users should have the right to opt out, where appropriate, and have access to a person who can quickly consider and remedy their problems.[53]

President Biden’s latest Executive Order on Artificial Intelligence, signed on October 30, 2023[54], outlines several key directives to ensure the safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of AI. The key topics covered by the Executive Order are presented below:

- AI Safety and Security Standards: The executive order mandates the creation of new safety and security standards for AI. This includes requiring developers of critical AI systems to share safety test results and other important information with the U.S. government before public deployment. Notably, this involves systems that pose serious risks to national security, economic security, or public health and safety. Agencies like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) are tasked with developing these standards.[55]

- Civil Rights: The order addresses potential discrimination and biases in AI usage, particularly concerning civil rights. It directs federal agencies to improve their efforts to prevent algorithmic discrimination. This includes a directive for the Department of Justice to work with other federal civil rights offices to coordinate responses to civil rights violations linked to AI technologies.

- Consumer and Labour Protections: The executive order aims to protect consumers and workers from AI-related risks. It calls on agencies to develop guidelines for AI in consumer and worker protection, such as detecting AI-generated fraud and enhancing privacy measures.

- International Collaboration: The executive order also emphasises the U.S.’s role in leading global efforts to manage AI risks. It promises to engage with international partners to develop a responsible framework for AI usage, aiming to foster a common approach to shared global challenges.

- Educational and Research Initiatives: The order includes support for AI education and research, promoting initiatives like the National AI Research Resource to provide AI researchers and students with essential resources and data. This is intended to bolster innovation and maintain U.S. leadership in AI technology.

- Regulatory Oversight and Government Use: There is a significant focus on enhancing the federal government’s capacity to use and regulate AI effectively. This includes setting standards for government procurement of AI technologies and ensuring these technologies are used in ways that protect public safety and individual rights.

- Implementation Timelines: The executive order sets specific deadlines for various actions, such as developing best practices for AI in criminal justice and creating standards for AI in education by late 2024. These timelines are crucial for ensuring timely implementation and accountability.

China. AI regulation has advanced beyond the proposal stage, with the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) leading the way in establishing rules controlling specific AI applications. The CAC’s approach is the most developed, rule-based, and focused on AI’s role in information dissemination.[56]

Interim Measures for Generative AI: China’s regulation focuses on generative AI services, emphasising respect for social morality, ethics, and core socialist values. It mandates stringent requirements in algorithmic design, data selection, and service provision to prevent discrimination and uphold rights such as privacy and intellectual property. The regulations also include provisions against content that could threaten national security, incite violence, or spread misinformation.[57]

Operational and User Protection Requirements: AI service providers must handle personal information carefully, with obligations to secure consent for using personal data and to provide clear information about data use. They are also expected to implement effective content moderation, improve the transparency and reliability of AI services, and provide mechanisms for user complaints and engagement.[58]

Enforcement and Penalties: The regulatory framework is supported by existing laws such as the Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law, and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). The PIPL, in particular, has significant implications for AI by setting strict guidelines for personal data protection and automated decision-making technologies. Violations of these regulations can lead to severe penalties, including fines and operational restrictions.

Future Directions and Concerns: China is expected to continue refining its AI regulations to address emerging issues, such as the challenges posed by generative AI in terms of copyright and IP rights. There’s also a growing emphasis on developing national platforms for testing AI safety and security and engaging third-party organisations to conduct regular AI assessments.[59]

The AI conundrum: Key challenges in regulating AI

AI presents one of the most difficult challenges to traditional regulation. Three decades ago, one could think of software being programmed. However, the way to think about it in terms of shifting to an AI environment is that the software is not programmed anymore; it is trained. Today, we are dealing with networks of information that often have surprising capacities. AI itself is not one technology or even one singular development. It is a bundle of technologies whose decision-making mode is often not fully understood, even by AI developers.

It is very difficult to relate something as technical as AI to robust regulation. On the one hand, most regulatory systems require transparency and predictability; on the other, most laypeople do not understand how AI works. The more advanced certain types of AI become, the more they become “black boxes”, where the creator of the AI system does not really know the basis on which the AI is making its decisions. Accountability, foreseeability, compliance, and security are questioned in this regard.

The “black box” problem

AI algorithms make strategic decisions, from approving loans to determining diabetes risk. Often, these algorithms are closely held by the organisations that created them or are so complex that even their creators cannot explain how they work. This is AI’s “black box” — the inability to see what is inside an algorithm.[60]

A study conducted by the AI Now Institute at NUY states that many automated decision-making systems are opaque to the citizens. Regulators have already started enacting algorithm accountability laws that try to curtail the use of automated decision systems by public agencies. For instance, in 2018, New York City enacted a local Law in relation to automated decision systems used by agencies. The Act created a task force to recommend criteria for identifying automated decisions used by city agencies, a procedure for determining if the automated decisions disproportionately impact protected groups. However, the law only permits making technical information about the system publicly available “where appropriate” and states there is no requirement to disclose any “proprietary information”.

Many are not made public because of nondisclosure agreements with the companies that developed them. The EU GDPR requires companies to be able to explain how algorithms use the personal data of customer’s work and make decisions — the right to explanation. However, since this right has been mentioned in Recital 71 of the GDPR many scholars point out that it is not legally binding. Article 22 of the GDPR states that EU citizens can request that decisions based on automated processing concerning them or significantly affecting them and based on their personal data are made by natural persons, not only by computers. In this case, you also have the right to express your point of view and contest the decision. [61]

Another illustrative example of AI’s black box in decision-making is the use of automated systems in recruitment and selection. Some companies have used hiring technology that analyses[62] job candidates’ facial expressions and voice to advise hiring managers. It has been feared that using AI in hiring will re-create societal biases. Regulators have already started tackling these legal conundrums. For instance, the new Illinois Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act aims to help job candidates understand how these hiring tools operate.[63]

Algorithmic bias

Many algorithms have been found to have inherent biases. AI systems can reinforce what they have been taught from data. They can amplify risks, such as racial or gender bias. Even a well-designed algorithm must make decisions based on inputs from a flawed and inconsistent reality. Algorithms can also make judgmental errors when faced with unfamiliar scenarios. This is the so-called artificial stupidity. Many such systems are “black boxes”; the reasons for their decisions are not easily accessed or understood by humans — and therefore difficult to question or probe. Private commercial developers generally refuse to make their code available for scrutiny because the software is considered proprietary intellectual property, which is another form of non-transparency.

Facial recognition algorithms have been proven to be biased when detecting people’s gender. Several cities, such as San Francisco and a few other communities, have banned their police departments from using facial recognition in the US.[64]

Legitimate news and information are sometimes blocked, illustrating the weaknesses of AI in determining what is appropriate. Examples have led to a growing argument that IT firms posting news stories should be subject to regulations similar to those that media firms face.

Deepfakes[65], computer-generated and highly manipulated videos or presentations, present another significant problem. Some governments have started regulating them. For instance, China has made publishing deepfake videos created with AI or virtual reality a criminal offence. From January 2020, any deepfake video or audio recording should be clearly designated as such; otherwise, content providers, which are expected to police the system, together with offending users, will be prosecuted.[66]

Principles of Regulating Transformative Technologies

Innovative and Adaptive

Traditional regulatory models are time-consuming and robust. It takes months and sometimes years to draft new regulations in response to market developments and technology push. This needs to change. The modern regulatory models are innovative and adaptive. They rely on trial and error and co-design of regulations and standards and have shorter feedback loops. Regulators can seek feedback using a number of “soft-law” innovative instruments. These instruments include policy labs, which bring together policymakers, technologists, and community members to prototype solutions, as seen in the Policy Lab UK. Other tools include crowdsourcing for legislative input, as practised by Iceland during its constitutional reform process; codes of conduct like the EU’s Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online; best-practice guidance such as the OECD’s Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises; and self-regulation mechanisms, exemplified by the technology industry’s adherence to privacy standards.[67]

Another illustrative example is Singapore, which has adopted progressive regulations for testing self-driving vehicles due to its high population density and limited space to expand. In 2017, Singapore modified its road traffic law to accommodate “automated vehicles’ technologies and their disruptive character. In order to ensure that regulations remain agile, the rules will remain in effect for five years, and the government has the option to revise them sooner. The autonomous vehicle testing falls under the purview of a single agency, the Land Transport Authority. The authority actively partners with research institutions and the private sector to facilitate pilots of autonomous vehicles.[68]

Regulatory Sandboxes. A regulatory sandbox is a safe space for testing innovative products and services without complying with the applicable set of regulations. The main aim of regulators establishing sandboxes is to foster innovation by lowering regulatory barriers and costs for testing disruptive innovative technologies while ensuring that consumers will not be negatively affected. The concept of regulatory sandboxes and any other form of collaborative prototyping environment builds on the tradition of open-source software development, the use of open standards and open innovation.[69]

Regulatory sandboxes are created by regulators around the globe. In 2018 Japan introduced a regulatory sandbox where foreign and domestic firms and organisations are able to demonstrate and experiment with new technologies such as blockchain, AI and IoT in financial services, healthcare, and transportation. These sandbox experiments also occur in virtual spaces rather than limited geographical regions like Japan’s National Strategic Special Zones. Sandboxes are a means through which new businesses are assessed, after which the government can introduce deregulation measures. Singapore announced the launch of two sandboxes on July 24, 2023. The sandboxes will provide a platform for government agencies and businesses to develop and test generative AI applications using Google

The Utah Supreme Court’s Office of Legal Services Innovation has implemented a novel approach to the regulatory sandbox concept. The program enables non-traditional legal service providers and technologies to operate in a controlled environment. The primary objective of this initiative is to discover new ways of offering affordable legal services. The program includes using AI in legal advice, among other innovations. [70]

Photo by Jared Brashier on Unsplash

Public agencies also take innovative approaches to regulating drones. For instance, the US is piloting a sandbox approach for drones. Beginning in 2017, the Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Integration Pilot Program has brought state, local, and tribal governments together with private sector entities, such as UAS operators or manufacturers, to accelerate safe drone integration. The Federal Aviation Administration has chosen 10 public-private partnerships to test drones. The pilot programs test the safe operation of drones in various conditions that are currently forbidden, such as flying at night or beyond the line of sight of operators, allowing companies to test applications, including medical equipment delivery, monitoring oil pipelines, and scanning the perimeter of an airport.[71]

Despite all opportunities, the concept of regulatory sandboxes has also raised some questions about the potential for creating market distortions and unfair competition if regulators become too close to and protective of the regulatory sandbox participants.

Policy Labs. A policy lab is a group of actors with various competencies in developing a regulatory framework. They deploy a set of user-centric methods and competencies to test, experiment, and learn to develop new policy solutions.[72]

Some states and local governments in the US have already established policy labs to partner with academia and use their administrative data to evaluate and improve programs and policies while safeguarding personal privacy. The policy labs provide the technical infrastructure and governance mechanisms to help governments gain access to analytical talent. These data labs help convert data into insights and drive more evidence-based policymaking and service delivery.[73]

Outcome-Focused

Unlike traditional prescriptive and input-based regulatory models, outcome-focused regulation is a set of rules that prescribe achieving specific, desirable, and measurable results. This offers the private sector greater flexibility in choosing its way of complying with the law.[74]

Outcome-focused regulations stipulate positive outcomes that regulators want to encourage. For instance, drone regulation can be prescriptive and focus on inputs: “One must have a license to fly a drone with more than xx kilowatts of power (not very helpful)”, or it can be outcome-based and focus on effects: “One cannot fly a drone higher than 400 feet, or anywhere in a controlled airspace (better)”.[75]

The transformative power of technologies like blockchain, IoT, and machine learning is evident in their ability to integrate and create more comprehensive and secure systems. For instance, blockchain technology can enhance the security of data collected through IoT devices, while machine learning can improve decision-making processes, such as in banking scenarios. To facilitate such innovative integrations, a regulatory environment that focuses on outcomes rather than prescriptive norms is beneficial, allowing innovators the flexibility to explore and develop these technologies effectively. This outcome-focused approach to regulation supports the idea that by setting clear, desirable goals, technological innovation can proceed without unnecessary constraints, fostering both creativity and compliance with overarching objectives such as safety and privacy.

Evidence-Based

Evidence-based regulation is a modern regulatory model that is data-driven and risk-based. It is dynamic and based on real-time data flows between the private sector and regulators. The data could then be compared with regulations to decide whether a firm is in compliance. Firms in compliance would be listed as safe, and if not, the data systems could produce a set of action items to meet the standard.[76]

The first capital city in the world to regulate ridesharing was Canberra, Australia. Before the service began, Uber signalled its intention to enter the local market, which prompted the local government to take a systematic and evidence-based approach to reform the ridesharing sector. The ridesharing business model differs from the traditional taxi industry regarding risk. The additional information that is available to both drivers and passengers through the booking service, such as rank and hail work by taxis, significantly reduces the risk involved with anonymous transactions. Additionally, a reputation rating system incentivises drivers and customers alike to behave respectfully. By integrating a booking system and payments, payment risks such as cash handling and non-payment have been minimised. The City of Canberra designed a new regulatory framework that is adaptable to new technologies by considering the approach to risk from different business models. It further anticipated the emergence of novel business models, such as fleets of automated vehicles providing on-demand transport. The designed system does not regulate individual businesses, but it provides a regulatory framework and promotes fair treatment of different business models, thus making the framework more flexible. The Government formally monitors the outcomes of the new regulatory framework by collecting qualitative and quantitative data on industry changes, including customer outcomes and impacts on various stakeholders.[77] This evaluation will be used to see if the industry is experiencing change that aligns with the modelled forecasts and to determine whether further actions are required.[78]

Open data has also been used by regulators to complement their own data. In the case of digital health software, a regulator could monitor products through publicly available data on software bugs and error reports, customer feedback, software updates, app store information, and social media.

Once the data flows are integrated, this part of the regulatory process can be automated. Enforcement can become dynamic, and reviewing and monitoring can be built into the system. For example, the City of Boston inspects every restaurant to monitor and improve food safety and public health. These health inspections are usually random, which can increase the time spent at restaurants following the rules carefully, thus missing opportunities to improve health and hygiene in restaurants with food safety issues. In Boston, the search for health code violations is narrowed down using a winning algorithm that uses data generated from social media. These algorithms detect words, phrases, ratings, and patterns that allow them to predict violations, thus helping public health inspectors execute their working duties better and more efficiently. This algorithm could allow the City of Boston to catch the same number of health violations with 40 per cent fewer inspections by simply better targeting city resources at dirty kitchen hotspots. As of 2017, these winning algorithms have been employed by the City of Boston and have found 25 per cent more health violations and surfaced around 60 per cent of critical violations earlier than before. The city has been able to catch public health risks sooner and get a smarter view of utilising scarce public resources by combining past data with new information sources.[79]

A Pre-Cert pilot program for digital health developers that demonstrate a culture of quality and organisational excellence based on objective criteria (e.g. software design, development, and testing) has been created by the US Food and Drug Administration. This program has been envisioned as a voluntary pathway embodying a tailor-made regulatory model that assesses the safety and effectiveness of software technologies without inhibiting patient access to these technologies. This is in stark contrast to the current regulatory paradigm. Because software as a medical device allows for a product to be adaptable and can respond to glitches, adverse events, and other safety concerns quickly, the FDA has been working to establish a regulatory framework that will be equally responsive when issues arise to help consumers continue to have access to safe and effective products. The idea behind this is to allow the FDA to accelerate the time to market for lower-risk health products and focus its resources on those posing greater potential risks to patients. This will enable pre-certified developers to market lower-risk devices without an additional FDA review or with a simpler market review, as the FDA monitors the performance of these companies continuously with real-world data.[80]

Collaborative

This ecosystem approach—when multiple regulators from different nations collaborate with one another and with those being regulated —can encourage innovation while protecting consumers from potential fraud or safety concerns. Private, standard-setting bodies and self-regulatory organisations also play key roles in facilitating collaboration between innovators and regulators.

In recent years, managing AI through a more cohesive global response has become increasingly important, as AI governance concerns are inherently international. AI governance systems are gradually becoming more collaborative, relying on public-private partnerships. There are many stakeholders involved in the governance of AI systems: government bodies (for instance, telecom regulators, data protection authorities, and cybersecurity agencies), private sector stakeholders such as the IEEE, civil society (examples are Algorithm Watch[81] or Derechos Digitales[82]) and international organisations such as the UN (with the landmark adoption by the UN General Assembly of the non binding Resolution on AI for safe, secure and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems for sustainable development), the ITU, the World Bank Group, UNESCO, GPAI, Globalpolicy.AI[83] and OECD.

Given AI’s versatility, governance approaches can no longer be designed in silos that focus solely on individual sectors like health, education, or agriculture. Successful AI governance depends on multi-stakeholder collaboration, ensuring the appropriate integration of AI solutions in the context of developing countries. Public-private partnerships, localisation, and cross-disciplinary cooperation among key stakeholders are essential for the successful development and deployment of AI.

One way forward is being developed by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum through the Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system, which fosters trust and facilitates data flows amongst participants. A key benefit of the APEC regime is that it enables personal data to flow freely even in the absence of two governments having agreed to recognise each other’s privacy laws as equivalent formally. Instead, APEC relies on businesses to ensure that data is collected and then sent to third parties, either domestically or overseas, and continues to protect the data in a manner consistent with APEC privacy principles. The APEC CBPR regime also requires independent entities that can monitor and hold businesses accountable for privacy breaches.[84]

For countries party to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the privacy commitments in the e-commerce chapter provide another framework for integrating privacy, trade, and cross-border data flows.[85]

The example of the fAIr LAC Initiative

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), in collaboration with partners and strategic allies, leads the fAIr LAC initiative, which seeks to promote the responsible adoption of AI and decision support systems. Initiatives like the IDB’s fAIr LAC are also important for changing challenges into opportunities. fAIr LAC works with the private and public sectors, civil society, and academia to promote the responsible use of AI to improve the delivery of social services and create development opportunities to reduce growing social inequalities. Their pilot projects and system experiments create models for ethical evaluation, as well as other tools for governments, entrepreneurs, and civil society to deepen their knowledge of the subject and provide guidelines and frameworks for the responsible use of AI. These resources also consider how to influence policy and entrepreneurial ecosystems in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) countries.

Source: https://fairlac.iadb.org/en

Key considerations for regulators

By working with key stakeholders from the private sector, the not-for-profit sector, and academia, regulators can ensure that they co-create an environment where transformative technologies are built with consumer safety, privacy and security in mind and where digital products and services are as inclusive and affordable as they are innovative. Transformative technologies are, therefore, a challenge that regulators can embrace if they are ready to adapt. This requires knowledge sharing and cross-sector collaboration between key stakeholders.

Regulators should create an enabling environment (governance institutions, policies and laws) for an effective roll-out of transformative technologies. Appropriate policies and regulatory measures include the establishment of data protection frameworks and sectoral regulatory frameworks and the promotion and adoption of international standards and international cooperation. Regulators should also ensure that adequate levels of privacy and security and handling of data are in place, for example, by regulating against the use of data without consent and by reducing the risk of identification of individuals through data, data selection bias and the resulting discrimination by AI models and asymmetry in data aggregation. This also includes addressing safety and security challenges for complex AI systems, which is critical to fostering trust in AI and big data for development.

In particular, regulators should consider the following[86]:

- Work towards a national AI and big data strategy through broad multi-stakeholder consultation. Having such a strategy and accompanying action plan is paramount to guiding the deployment of AI and big data for development.

- Develop public sector AI and data expertise, with leadership in relevant government institutions. This can be done through collaboration with universities and other institutions already working on AI in the country, as well as with regional and international organisations.

- Create codes of conduct for the responsible use of AI and data in the public sector.

- Create rules governing AI transparency, liability, accountability, justification and redress for AI decision-making.

- Ensure that national AI and data policies cover issues such as data access and sharing, data protection and the use and management of open data.

- Regulations should be innovative and agile through the deployment of public-private partnerships. Public and private stakeholders should work together to develop common resources, databases, platforms and tools that are open, use privacy as a safeguard and encourage development. They should deploy innovative regulatory instruments that offer flexibility, such as regulatory sandboxes and public policy labs. Governments should also establish “cross-functional teams” across ministries and tiers of government.

- Clear and robust national policies and legal frameworks need to be developed to regulate consumer opt-in and opt-out data policies, data mining, access, use, reuse, transfer and dissemination. These policies should enable citizens to better understand and control their own data, protect against attacks by hackers, while still allowing access to and reuse and sharing of non-personal information. At the same time, people’s rights to freedom of expression using data while respecting privacy boundaries should be protected.

- Strengthen the implementation and enforcement mechanisms of transformative technologies regulations and strategies. This will require a coordinated effort among different public and private sector stakeholders and will need to tackle issues such as privacy of personal data and information security.

- Ensure that AI for development is ethical and trustworthy, i.e., fair and unbiased, transparent and explainable, responsible and accountable, robust and reliable, privacy compliant, safe and secure, diverse and inclusive and human centred. In this context, policymakers should create rules to govern AI transparency, liability, accountability, justification, and redress for AI decision-making.

- Incorporating human rights considerations into technology regulations, ensuring that technology development and deployment do not infringe upon fundamental human rights, such as the right to privacy, freedom from discrimination, and freedom of expression. Regulators should collaborate with human rights organisations to identify potential risks and establish guidelines that uphold these rights in the context of emerging technologies.[87]

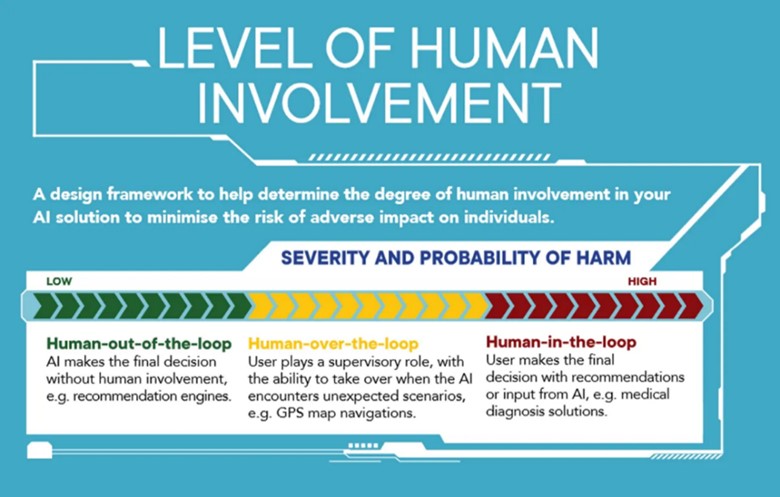

Integrate the “Human in the loop principle” and risk-based approaches to AI governance in national regulatory systems. To ensure the efficiency and safety of AI-driven applications, it is crucial for governance stakeholders to maintain a human “in the loop”. This means that AI should not completely replace humans but rather work in conjunction with adequately trained professionals who can validate AI decisions. The effectiveness of AI relies on the quality of data, human capital, and the expertise of the interdisciplinary team responsible for its development. It is essential to be able to measure the level of risk and impact of AI systems. Policymakers are advised to use a traffic-style system to determine the risk level posed by AI systems. A useful risk-based assessment framework is provided by the EU AI Act.

Level of risk defined by the EU AI Act

- Unacceptable risk: the deployment of the AI system should be banned (red)

- Medium risk: certification or algorithmic impact audits/assessments are required (yellow)

- Limited or no risk: no special due diligence required (green)

It is also crucial to determine the requirement for human oversight based on the use case, its sensitivity, the complexity and opacity of the algorithm, and the potential impact on human rights – whether this implies the human is “in the loop”, “on the loop” (HOTL), or “in command” (HIC).[88] The framework developed by the Government of Singapore can be helpful in this regard (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Level of human involvement in AI deployment

Source: IMDA & PDPC (2020).

- ITU (2021) Emerging technology trends: Artificial intelligence and big data for development 4.0, available here. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fintech.asp ↑

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sharing-economy.asp ↑

- https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/travel-leisure/article/2153851/how-airbnb-founders-went-cash-strapped-roommates ↑

- https://www.theverge.com/2019/12/19/21029606/airbnb-estate-agent-eu-ruling-platform-regulation ↑

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/dec/20/uber-european-court-of-justice-ruling-barcelona-taxi-drivers-ecj-eu ↑

- Products Liability Law as a Way to Address AI Harms, https://www.brookings.edu/research/products-liability-law-as-a-way-to-address-ai-harms/ ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=63199 ↑

- https://www.wired.com/2016/06/50-million-hack-just-showed-dao-human/ ↑

- https://autotechreview.com/features/flood-of-data-will-get-generated-in-autonomous-cars ↑

- ITU (2021) Emerging technology trends: Artificial intelligence and big data for development 4.0, available here. ↑

- https://www.wired.com/story/wired-guide-personal-data-collection/ ↑

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/jessicabaron/2019/02/04/life-insurers-can-use-social-media-posts-to-determine-premiums/#42002dc823ce ↑

- https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2019/06/26/why-data-ownership-is-the-wrong-approach-to-protecting-privacy/ ↑

- https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/cons-protection/rpt-fintech-and-consumer-protection-a-snapshot-march2019.pdf ↑

- ITU (2021) Emerging technology trends: Artificial intelligence and big data for development 4.0, available here. ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection_en%5d ↑

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf ↑

- Council of Europe (2017), Study on the human rights dimensions of automated data processing techniques (in particular algorithms) and possible regulatory implications, available here ↑

- https://nature.com/articles/s41467-019-10933-3 ↑

- https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/cons-protection/rpt-fintech-and-consumer-protection-a-snapshot-march2019.pdf ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Stankovich (2023) Unlocking the Potential of Generative AI in Cybersecurity: A Roadmap to Opportunities and Challenges, https://dai-global-digital.com/unlocking-the-potential-of-generative-ai-in-cybersecurity-a-roadmap-to-opportunities-and-challenges.html ↑

- https://www.juniperresearch.com/press/press-releases/iot-connections-to-grow-140pc-to-50-billion-2022 ↑

- https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/m/en_us/network-intelligence/service-provider/digital-transformation/knowledge-network-webinars/pdfs/1211_BUSINESS_SERVICES_CKN_PDF.pdf ↑

- https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/gartner-predicts-our-digital-future/ ↑

- https://www.tractica.com/newsroom/press-releases/more-than-75-million-wearable-devices-to-be-deployed-in-enterprise-and-industrial-environments-by-2020/ ↑

- https://www.pwc.co.uk/services/risk/technology-data-analytics/data-protection/insights/the-internet-of-things-is-it-just-about-gdpr.html ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- https://www.pwc.co.uk/services/risk/technology-data-analytics/data-protection/insights/the-internet-of-things-is-it-just-about-gdpr.html ↑

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/631043/IPOL_BRI(2019)631043_EN.pdf ↑

- Stanford University, Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2023, available here ↑

- Rudra (2023) ChatGPT in Education: The Pros, Cons and Unknowns of Generative AI, available here ↑

- Italian Garante (2023) ChatGPT: OpenAI riapre la piattaforma in Italia garantendo più trasparenza e più diritti a utenti e non utenti europei, available here ↑

- Canadian Guardrails for Generative AI – Code of Practice (2023), available here ↑

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/g7-hiroshima-leaders-communique/ ↑