The regulation of price bundles

27.08.2020Introduction

According to research conducted by Ofcom in the United Kingdom (Ofcom 2020b: 22), U.K. customers make an average saving of 20-28 per cent, compared with purchasing the same services individually. Not surprisingly, these savings have led to 80 per cent of customers purchasing their electronic communication services in bundles,[1] but Ofcom also found (Ofcom 2020a: 19) that not all consumers are benefiting, with the 41 per cent of customers who do not recontract or switch provider at the end of their contract period missing out on the available savings.

Price bundles are both a boon for customers and an area of significant regulatory concern. Regulation of price bundles is designed to mitigate the potentially negative effects of bundles on the development of competition, while also enhancing consumer welfare.

Why bundle?

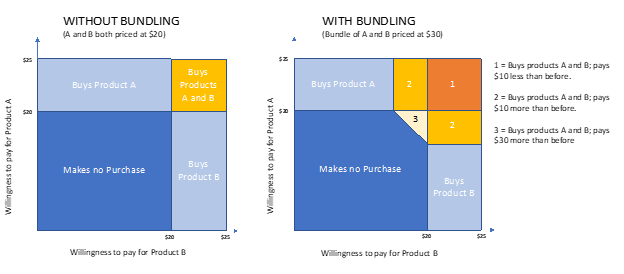

Source: Oxera 2007.

There are many good reasons for selling services in bundles. Principal amongst them are efficiency improvements on both the supply side and the demand side, which can lead to lower consumer prices and/or higher supplier profits.

Supply-side efficiencies arise from economies of scope. Most of the economies of scope are at the retail level (e.g. lower costs of sales, marketing, and billing) because product convergence leads to a simplification of the customer relationship. Although selling multiple products (e.g. fixed broadband, fixed line voice, and digital TV) can result in substantial economies of scope at the wholesale network level, these efficiency gains are not the result of bundling: they are equally available when all three services are sold jointly but separately.

Demand-side efficiencies arise from the simplification of the service offer to the customer, who has to spend less time and effort selecting services individually and will benefit from a single bill and a single contact point for customer service. The bundled product may therefore offer greater consumer value than the sum of its parts, and this will tend to grow the size of the market and result in further economy of scale effects. These demand-side effects are shown in the figure above, which considers two products for each of which consumers are prepared to pay a maximum of USD 25. When sold separately at USD 20, only a small group buys both products, but the potential market grows significantly when a bundled offer of USD 30 for both products is introduced.

What are the regulatory concerns?

As with many innovations, bundles benefit consumers as long as they are offered within a competitive market. However, suppliers in a dominant market position are able to use bundles for leverage of their dominance, both vertically and horizontally, with potentially anticompetitive impacts.

Vertical leverage occurs when a supplier exploits its significant market power (SMP) at the wholesale level to gain competitive advantage at the retail level. In practice this is unlikely to arise because the supply-side efficiency gains from bundling occur at the retail level rather than the wholesale level. As long as alternative retail service providers have access to wholesale inputs from the SMP supplier on cost-based terms, then they will be able to compete in the downstream retail market. In effect, they will be able to create the same retail bundles at the same wholesale cost as the SMP operator, so they can compete effectively. It is worth noting, however, that if wholesale prices are set on a retail-minus basis, then for bundled products the retail price benchmark (from which wholesale prices are derived) needs to be adjusted downwards to reflect the savings available from bundling.

Horizontal leverage is a more challenging regulatory issue. This involves an SMP supplier in one retail market (e.g. fixed telephony or fixed broadband) using bundles to leverage its market advantage into other retail markets (e.g. digital TV or mobile). It could do this by setting a competitive (low) price for the bundle but within it the price of the SMP product may be excessively high, while the price of competitive products is excessively low. To some extent this problem can be mitigated by regulators banning unreasonable bundling and enforcing “mixed bundles” rather than “pure bundles”, i.e. the individual products have to be sold separately as well as within the bundle. However, regulators still need to be on guard to ensure that there are no cross-subsidies within the prices charged, either in the bundle or in the individual services sold outside of it.

Using cost models to regulate price bundles

Effective regulation of price bundles requires a good understanding of the costs of supplying each of the relevant services within the bundle. Furthermore, the relevant costs are those of a reasonably efficient operator (not necessarily the actual costs of the SMP provider) and two thresholds need to be assessed:

- A price ceiling. This is the maximum allowable price for each individual service within the bundle. Pricing above this level would be designated as excessive pricing. The price ceiling is typically set at total service long run incremental costs, plus a mark-up for common and joint costs (TSLRIC+). The mark-up itself would reflect the retail costs of supplying each service individually.

- A price floor. This is the minimum allowable price for the bundle as a whole. Pricing below this level would be designated as predatory pricing. The price floor is typically set at average avoidable cost (AAC),[2] which represents the difference in total costs with and without the supply of each of the bundled services.

Regulators that construct bottom-up LRIC models will generally be able to derive these cost estimates for relevant services as if supplied by a modern efficient operator. In many cases, several different cost models will be required (e.g. for fixed access, mobile access, TV distribution, submarine cable access), however the example that follows is based entirely on a mobile network cost model.

Retail mobile services are now largely sold in bundles, comprising voice, text, and data. If there is an SMP provider in the retail mobile services market, it could exploit its market position by setting low prices for on-net calls, to attract and retain customers. Competitors could not profitably match because for them the cost of calls to those customers is much greater (as they are off-net calls and require payment of a mobile termination rate).[3] So, there is a high risk of predatory pricing of bundles.

Hypothetical example

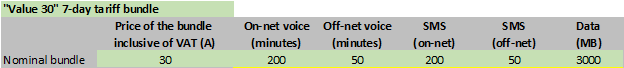

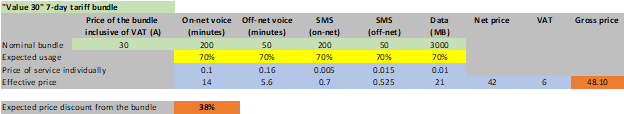

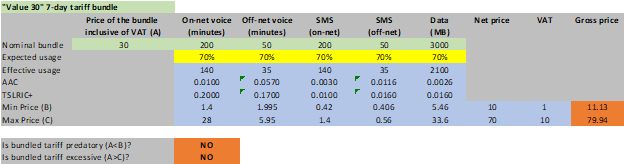

The table below shows a fictitious example of a mobile price bundle offered by an SMP operator.

The tariff may need to be submitted to the regulator for approval before it is launched.[4] The regulator may consult its BU-LRIC cost model to obtain information about the costs of each service, as well as retail and wholesale price information as follows:

Given this information, the regulator has to assess whether the bundle may constitute predatory or (less likely) excessive pricing.

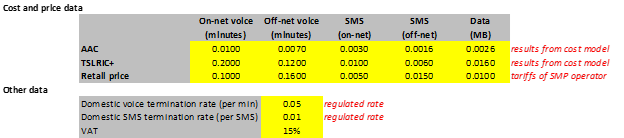

The first step is to compare the expected average price of the bundle with the sum of the individual service prices. To do this the regulator has to assess the likely extent to which the bundle will be used. Usage will likely be lower than 100 per cent, especially if the bundle is large or the validity period is quite short. For the “Value 30” bundle, the validity period is only seven days, so the regulator estimates an average usage of, say, 70 per cent.[5] On this basis, it can be seen that the bundle provides a 38 per cent discount on the individual service prices.

To check for predatory pricing, the price of the bundle has to be checked against the aggregate AAC for the component elements. Similarly, to check for excessive pricing the price of the bundle has to be checked against the aggregate TSLRIC+ for the component elements. When this is done, the regulator determines that the bundled price (30) sits comfortably between the price floor (11.13) and the price ceiling (79.94). So, it can confidently approve the tariff.

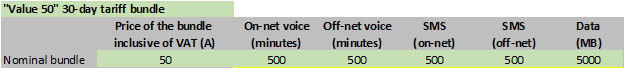

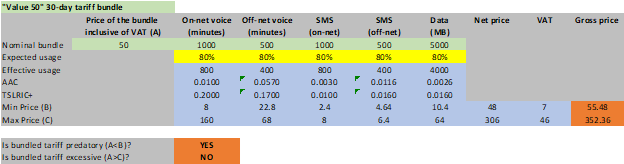

On other occasions the regulator may have to reject tariffs that, while attractive to customers, are anticompetitive. Take, for example, the “Value 50” proposed by the same SMP operator to the same regulator.

This time the regulator notes that the validity period is longer (30 days rather than seven days) and therefore decides to increase the average utilization of the bundle to 80 per cent. Otherwise the analysis is the same as before, but this time it turns out that the bundle does constitute predatory pricing.

It is worth noting that it is often the off-net calls and SMS that cause the problem. Whereas on-net voice and SMS have miniscule cost in the modern data-centric network, off-net services have higher costs because they include termination rates to be paid to another network operator. In the examples shown above, separate allowances are given for on-net and off-net calls and SMS, however the same logic would apply even if the bundle did not separate on-net and off-net traffic. Regulators have to remain vigilant to prevent the long-term interests of end users (through healthy and sustainable competition) being jeopardized by the immediate attraction of lower prices.

Endnotes

- This trend is not limited to the UK. According to BEREC (2018: 15) 83 per cent of EU customers purchase fixed broadband in a bundle: 75 per cent with fixed voice and 35 per cent with mobile. ↑

- AAC is alternatively called pure LRIC. ↑

- Of course, this differential works the other way around as well: there is a higher cost for the SMP operator to handle calls to the other operator. However, the disparity in scale coupled with strong network effects means that cross-subsidizing on-net calls is attractive to the SMP operator but not to its competitors. ↑

- This scenario accords with that described in the Digital Regulation Platform case study on “Iran tariff approval and notification procedures.” Alternatively, the regulator may review the tariff on an ex-post basis. ↑

- Instead of estimating a realistic usage level it would be possible to use the theoretical maximum usage within the bundle. However, this will unrealistically increase the imputed cost of the bundle, and make it harder to demonstrate predatory pricing. Also, this approach is not possible if the bundle is “unlimited.” It is therefore better to estimate the likely actual usage of each bundle, ideally by empirical research. ↑

Notes

- sage of each bundle, ideally by empirical research. ↑

References

Ofcom. 2020a. Helping Consumers Get Better Deals: A Review of Pricing Practices in Fixed Broadband. London: Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/168003/bb-pricing-update-july-20.pdf.

Ofcom. 2020b. Pricing Trends for Communications Services in the UK. London: Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/189112/pricing-trends-communication-services-report.pdf.

BEREC (Body of the European Regulators for Electronic Communications). 2018. European Benchmark of the Pricing of Bundles – Methodology Guidelines. BoR (18) 171. Brussels: BEREC. https://berec.europa.eu/eng/document_register/subject_matter/berec/regulatory_best_practices/methodologies/8255-european-benchmark-of-the-pricing-of-bundles-8211-methodology-guidelines.

Oxera. 2007. Bundling and Retail Minus Regulation: Developing an Imputation Test. Oxera Consulting report for the Commission for Communications Regulation. https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Bundling-and-retail-minus-regulation.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022