The infrastructure sharing imperative

25.08.20221 Infrastructure as a societal asset

People rely on network infrastructure almost every day, from the moment they wake up until the moment they go to sleep (and often through the night as well). Water, electricity, gas, roads, rail and telecommunications underpin modern societies throughout the world. But for most people most of the time they are so taken for granted as to be almost invisible. It is almost impossible to imagine a world without utilities: disparate, pre-industrial, subsistence communities with minimal interaction between them.

Despite its ubiquity and critical importance, infrastructure is under threat. War, famine, a pandemic, climate change, the spiralling cost of living, and a crisis of confidence in the global market economy, have all heaped pressure on utility infrastructure. In high income countries much of that infrastructure is reaching the end of its economic life and is not fit for modern purposes: but how can heavily indebted societies afford its replacement? In the least developed countries the absence or inadequacy of infrastructure has long held back economic development and the “infrastructure gap” continues to widen, as international aid contracts and the battle for investment dollars intensifies.

A major rethinking of the role of infrastructure is now underway. Instead of being privatised and liberalised, there is growing momentum behind public ownership and shared usage. Instead of seeing each utility as a separate silo, there is a fresh understanding of the need for communication and co-operation (and possibly convergence) between those entities handling roads, energy, water and telecoms. The key to meeting climate-critical decarbonisation targets is a whole-system approach that involves telecoms, data, energy and transport, and recognises their essential interconnectivity. Underpinning all of this is the recognition that utility infrastructure is a societal asset that should and can be deployed for the common good. But for this to happen, infrastructure sharing is an essential requirement.

2 The need for infrastructure sharing

The major privatisation and liberalisation of utilities that started with telecom networks in 1980s was driven by a policy objective of increased investment, innovation and efficiency. It largely worked. Utility companies were awoken from a bureaucratic slumber, investment poured in, and a degree of competition was achieved, especially in retail services. Consumers had choices and prices fell, owing to the combined pressure of market forces and sectoral regulation.

During the liberalisation process many attempts were made to establish competition at the infrastructure level as well as in services. On fixed networks this proved very difficult: the costs of developing alternative network infrastructure proved too much of a barrier. However, at roughly the same time the telecommunications industry was transitioning to mobile technology, and most countries succeeded in establishing two, three or more competing mobile networks.

For a while it appeared that the goal of infrastructure competition was obtainable. Economic theories such as the “ladder of investment” suggested that full competition could be achieved incrementally so long as prospective entrants had access to a range of wholesale access products that allowed them to ramp up their own infrastructure investments gradually. Under these conditions the need for infrastructure sharing was limited and restricted to dominant suppliers and enduring bottleneck facilities. It was even possible to see infrastructure sharing as detrimental to the progress of full competition, giving entrants an easy way out of making their own infrastructure investments.

There is no longer much optimism around infrastructure competition. Partly this is due to the need for unprecedented levels of investment in fibre and 5G networks coupled with a shrinking and highly competitive market for investment dollars. But, more fundamentally, there has been a realisation amongst policy-makers and industry stakeholders that infrastructure sharing and co-investment models offer greater benefits at lower costs. This article explores what those benefits are and how they can best be achieved.

3 Models of infrastructure sharing

Infrastructure sharing is an intuitive term, but one that is hard to define. Most articles on infrastructure sharing provide examples of the practice but few offer a precise definition. This is because there are numerous infrastructure elements that could be shared and numerous ways in which that sharing may be arranged. This leads to an open-ended definition along the following lines[1]:

Infrastructure sharing means various kinds of arrangements by which an owner of telecommunication network facilities (including but not limited to, antennas, switches, access nodes, systems, ducts, poles, towers, premises and rights of way) agrees to share access and usage of those facilities with another legal entity, normally another network operator or service provider, subject to a commercial agreement between the parties.

Such a definition indicates that there are at least three dimensions to an infrastructure sharing agreement:

- Who is infrastructure owner?

- Who is being granted access to the owner’s infrastructure?

- What facilities are included?

- What form does the commercial agreement take?

Establishing the answers to these questions establishes the critical characteristics of infrastructure sharing agreements. Different forms of agreement result in different economic and market outcomes and give rise to different regulatory challenges.

In this section we consider four of the most common dimensions to infrastructure sharing arrangements and consider their regulatory implications.

3.1 Active v Passive Sharing

Passive infrastructure sharing is where non-electronic infrastructure such as towers, poles, ducts and premises are shared but all the active network electronics remains proprietary to the individual network operators. Passive infrastructure sharing is technically the simplest form of infrastructure sharing, but it offers less scope for cost-savings than active infrastructure sharing.

Active sharing includes electronic infrastructure such as switches and radio access nodes as well as passive network elements. This offers greater scope for cost reduction, but significantly complicates the operational procedures and makes service differentiation difficult. There are also various sub-categories of active infrastructure sharing, particularly for mobile networks, depending on how deeply the active electronics are shared:

- MORAN (multi-operator radio access network) – where the components of the radio access network are shared, but each operator is assigned its own dedicated radio spectrum

- MOCN (multi operator core network) – where radio network elements and spectrum are shared, but each operator maintains its own core network

- National roaming – where the entire mobile network is shared, for example to extend the service coverage area of a smaller network operator.

The operators and the regulator may have different perspectives on active vs passive sharing. For operators the key issue is the balance between savings in capital investments and increases in operational costs associated with infrastructure sharing. Operators may also be concerned that the greater the extent of infrastructure sharing the greater the complexity of operation and the less the opportunity to differentiate on quality of service. For regulators the main concern is arrangements that foreclose markets to competition.

3.2 One-way v Reciprocal Sharing

The simplest forms of infrastructure sharing are where one operator (the Access Provider) leases space to another operator (the Access Seeker). This is a one-way relationship of buyer and seller. There could, of course, be multiple buyers if several different service providers are all seeking access to the same network. Regulators will therefore be concerned to ensure that the same terms and conditions are offered to each access seeker or at least that any variation is cost-justified, preferably through a published access price list.

Reciprocal sharing creates a more complicated situation and is potentially of greater regulatory concern. A typical situation is where two operators with different geographic coverage areas reach an agreement to share access to their networks in the areas unserved by the other network. This reciprocal arrangement allows each operator to extend its network coverage, and thus benefits users on either network. However, because the agreement is reciprocal there may be no charges involved or, if there are charges, they are unlikely to reflect the full cost of service. For a regulator these are warning signs of collusion and the potential for anti-competitive behaviour, especially if there are other service providers in the end user market which are excluded from the agreement.

4 Designing infrastructure agreements

The design of infrastructure agreements should be left to the parties involved in the agreement. However, model agreements could usefully be drawn up by the regulatory authority and/or principles for the drafting of such agreements should be published by the regulator. One recent study (CERRE 2020, p36) has identified the following six principles to be critical:

- Access or transfer prices should not be set at excessive levels. Where infrastructure sharing is mandated, the prices should be fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory, with the further possibility of cost-based pricing for operators with significant market power. Even for commercially negotiated agreements, there should be clarity on the access prices as well as internal transfer prices that may apply to the infrastructure owner. By such means agreements can, if necessary, be reviewed ex-post by the competition authority and their effect on market outcomes determined.

- The strategic independence of each partner should be guaranteed. This is important to mitigate against the disincentives for the access seeker to invest in its own infrastructure and compete across a broader facilities base. This requires the freedom to independently design their services and set quality parameters, customer intelligence and service design should be kept separate and confidential, and the ability to develop independent strategic plans.

- Wholesale access to third parties should be guaranteed. Each party should be allowed to offer wholesale access to its own infrastructure, and to its portion of joint infrastructure, individually and independently, so long as doing so does not adversely affect the quality of services available to the other partner. This is important in order to avoid foreclosure of downstream markets.

- Exclusivity provisions for entering the agreement should be kept to the minimum necessary. Some exclusivity may be required so that the agreement is attractive to both parties, but other (potential) competitors will be at a disadvantage if access is unreasonably restricted.

- The agreement should protect the investor against opportunism from later co-investors. This is important to protect first-mover advantages and attract as much investment as possible as soon as possible. The principle is the same whether the sharing agreement is commercially negotiated or mandated by regulation. In the latter case, the regulator must take care to ensure that there is a greater rate of return for to the original investor(s) than for later co-investment.

- Information exchange should be kept to the minimum necessary, and termination rules should be detailed and explicit. These principles guard against forms of tacit collusion. Transmission of commercial and strategic information re infrastructure facilitates collusion in downstream markets, so only information which is necessary to jointly plan network rollout should be transmitted between partners. Detailed rules on contract termination, including time schedules, are necessary to avoid either party manipulating the other through threats of abrupt and potentially harmful contract termination.

5 Infrastructure ownership

A further dimension to infrastructure sharing agreements is that of asset ownership. There are two main variations from the simple arrangement of a buyer and a seller:

- Third-party ownership. In this model ownership of the infrastructure assets (either passive, active or both) are passed to an independent company. A typical example is the transfer of mobile towers to a separate tower company which then leases the assets back to the mobile network operator. By this means the risks of capital investment (and associated risks) are taken off the books of the network operator and replaced by operational expenditure. From the operator’s perspective this may lighten the balance sheet and shield some income from sector-specific taxes, as well as distancing it from infrastructure sharing arrangements with other network operators. Such an arrangement may also satisfy the regulatory agenda of promoting infrastructure sharing, but the regulator may need to investigate the financial arrangements that are made to ensure that they do not unduly favour the divesting operator.

- Joint venture ownership. In this model the parties sharing infrastructure form a joint venture company to own and operate the network, so that their shared infrastructure is consolidated and independently managed. This can be especially attractive where operators are seeking to make shared investment in new technologies or in new geographical areas. Financially this has a similar impact to third-party ownership, but it allows them to retain joint control of the assets and the transfer prices paid for their usage. On the downside, there are costs involved in setting up and running the new organisation, and it is harder for either party to exit if the JV does not work out well. Regulators will also need to be vigilant for contractual terms that are exclusionary or otherwise anti-competitive.

6 The economic case for infrastructure sharing

6.1 Benefits

There are a large number of potential benefits arising from infrastructure sharing, which can be classified under five key themes:

- Efficient use of scarce resources. There are economic and environmental costs in network duplication. Sharing space on mobile towers or ducts avoids the need for constructing new towers or digging up roads to lay further ducts or cables, thus reducing consumption of scarce resources such as land, energy and raw materials. This in turn help to protect the natural environment and reduces the carbon footprint of the telecom industry and contributes towards net-zero emissions targets.

- Lower industry costs. For any given service output, the sharing of infrastructure avoids the cost of constructing and maintaining duplicate infrastructure. A report by BEREC suggests that infrastructure sharing could reduce capital expenditure by up to 45% and operational expenditure by up to 33% (BEREC, p16).

- Increased network coverage. The cost-savings brought about by infrastructure sharing can be translated into greater economies of scale and, under the right regulatory conditions in which the risk of investment is also shared, this can lead to an acceleration of coverage in higher-cost remote and rural areas.

- Enhanced competition. “Infrastructure sharing enables competing operators – especially new entrants – to compete more effectively with incumbent operators who control a significant amount of infrastructure which it is not economically feasible to replicate.” (ITU 2021, 25)

- Lower consumer prices. Although not all cost savings from infrastructure access are likely to be passed on to consumers, multi-operator service provision creates the competitive market conditions in which consumer price reductions do generally occur. Evidence from the ITU Tariff Policies Survey (ITU 2021, 34) shows that 15-25% of regulatory authorities believe that infrastructure sharing has resulted in lower end-user prices (and a similar number did not have data available to answer the question). There could also be some increase in the quality of service received by customers (e.g. spectrum sharing may allow for higher peak data rates to be provided).

These potential rich pickings have encouraged many national policymakers and regulators to seek the mandatory provision of infrastructure sharing. In doing so they have also encountered a number of challenges and downsides to infrastructure sharing.

6.2 Downsides

The challenges and risks associated with infrastructure sharing may be summarised as follows:

- Reduced incentives to investment. Whereas infrastructure sharing increases the efficient usage of existing infrastructure, it may dampen enthusiasm for additional investment if the return on investment is perceived as lower or less certain. This is an issue particularly for passive infrastructure sharing where the host operator may be burdened with active components from other companies while receiving a very low margin on its asset base.

- Reduced network resilience. The lack of competing infrastructure with fewer independent networks, both increases the burden on the remaining network(s) and means that the effect of any outages will be more widespread. Robustness in case of disaster or emergency will also be reduced.

- Risks of collusion. Particularly where active network elements are shared, operators may not be able to distinguish between their end-user services neither in service quality nor cost. This will dampen competition and may result in collusion, preventing otherwise viable operators from entering the market. In some cases (e.g. France, Ireland) regulators have banned active infrastructure sharing in urban areas so as to allow full infrastructure competition to be sustained.

- Operational challenges and costs. The more infrastructure sharing that exists the harder it is for infrastructure owners to plan and manage. Co-ordination between the parties is critical but also time-consuming and complicated, especially if competitive neutrality is to be maintained. Where space is limited (i.e. demand is greater than supply) rules need to be established to ensure fair and equal access to the existing resource and any investment to increase the available space.

6.3 Positive overall impact

Although there are downsides as well as benefits from infrastructure sharing, a positive overall view of infrastructure sharing is widespread amongst regulatory authorities across the world. In the ITU’s annual survey of tariff policies, respondents were asked if infrastructure sharing had the impact of reducing retail prices. Although a large number of respondents said that no information was available, for those that did, over 80% thought that infrastructure sharing did reduce prices, and the picture was consistent across all regions. See Figure 1.

The challenge for regulation is to establish the conditions that maximise the benefits, minimise the downsides and create the environment for infrastructure sharing to make a positive economic impact. Some have called this situation “co-opetition”.

6.4 Conditions for co-opetition

Co-opetition (a portmanteau word derived from co-operation and competition) refers to a collaborative arrangement between two or more competing firms to create value based on their shared resources. In co-opetition firms may co-operate fully in some functional areas but compete intensely in others. Firms in co-opetition are generally motivated to collaborate in ways that increase the size of their existing markets and/or allow them to enter new markets.

Infrastructure sharing has the potential to be an area of collaboration which enables the infrastructure provider to increase the returns from its investment (grow its existing market) while simultaneously allowing the access seeker to enter new markets (service provision within the geographical footprint of the shared network). However, a study of infrastructure sharing amongst mobile network operators in Sub-Saharan Africa (Arakpogun, 2020), found that the emergence of effective co-opetition was not guaranteed, and depended on a mix of institutional, market and technological factors. In particular, it concluded that[2]:

“Where infrastructure sharing was mandated, the incumbent MNOs engaged in passive collaboration, which entails following the minimum legal requirements. This practice has led some MNOs to be reluctant to invest in new networks or engage in network upgrades and technology development due to the lack of a clear regulatory framework and institutional incentives. However, in contexts where a ‘softer’ approach was adopted or where infrastructure sharing was not mandated at all, sharing practices emerged over time with encouragement from regulator.”

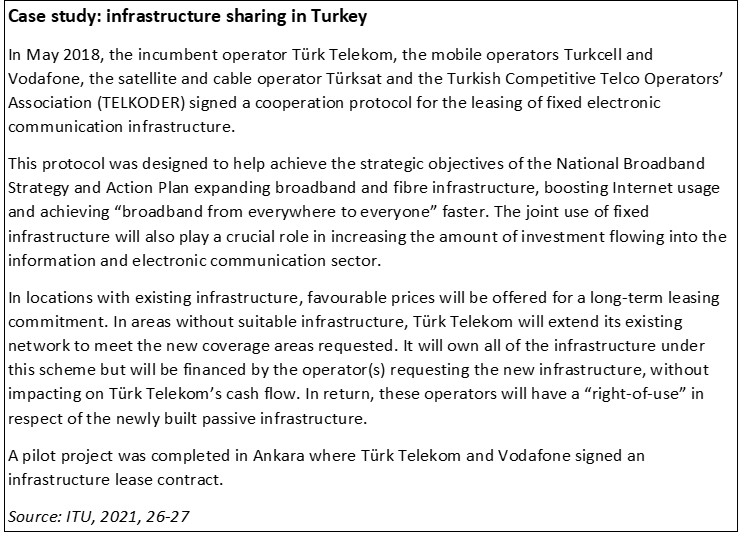

It is evident from this research that mandated infrastructure sharing is not necessary for effective co-opetition and may well be counterproductive. In some cases it may be better to offer incentives to the industry to ensure that economically efficient infrastructure sharing takes place via commercially negotiation. Table 1 provides some examples of incentives that have been proposed (not always implemented) in Africa.

Table 1: Regulatory incentives to encourage infrastructure sharing in Africa

Source: Arakpgun, 2020

Overall, it is clearly the case that infrastructure sharing involves a trade-off between allocative efficiency benefits and dynamic benefits of competition. For example, European Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, commented on a proposed network sharing agreement in the Czech Republic as follows[3]:

“Operators sharing networks generally benefits consumers in terms of faster roll out, cost savings and coverage in rural areas. However, when there are signs that co-operative agreements may be harmful to consumers, it is our role to investigate these and ensure that markets indeed remain competitive. In the present case, we have concerns that the network sharing agreement between the two major operators in Czechia reduces competition in the more densely populated areas of the country.”

The extent of competition concerns depends on the details of the network sharing agreements involved. The challenges for regulators are significant but, according to a BEREC survey, most national regulatory authorities do not see the barriers as insurmountable nor as presenting a major negative impact, “especially if sharing agreements are properly framed by regulation” (BEREC, p16).

7 The role of regulation

The policy objective for infrastructure sharing is clear and straightforward: there should be as much sharing as technically feasible and economically desirable. This will minimise the overall costs of the industry, avoid unnecessary duplication and environmental disruption, and ultimately leading to improved service availability and lower prices. The role of regulation is to make all of this happen; but that part is neither clear not straightforward.

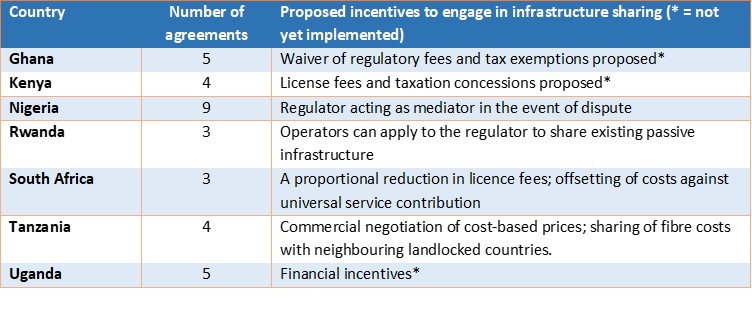

There are some well-accepted basic principles that should be followed in regulating infrastructure sharing. The guidelines developed by Communications Regulatory Authorities of Southern Africa (CRASA) are oft-quoted and they provide a good starting point (see box).

In practice a more nuanced implementation will be required, and the following sections explore some of the key issues involved.

7.1 Obligations on all operators or just those with SMP?

The CRASA guidelines suggest that infrastructure sharing should be required of all network operators and not just those with SMP (although the latter should additionally be required to publish a Reference Access Offer, RAO). There are also different and complementary reasons for regulating SMP operators which normally require an obligation beyond simply publishing a RAO.

A good example is the Physical Infrastructure Market Review carried out by OFCOM in the UK (OFCOM 2019). Although it considered all forms of physical infrastructure that could be deployed in the provision of electronic communication services, it found that:

- Not all infrastructure is equally valuable. In particular, there are disadvantages in using other utility infrastructure instead of specific telecommunications infrastructure. Some infrastructure (e.g. gas networks, sewer systems) may be unsuitable for telecommunications facilities. Other infrastructure may be technically suitable but suffer from other constraints, such a lack of access points, restrictive rules on access, construction incompatibilities, lack of suitable sites for hosting technical facilities, contractual complexities and require civil works to be made ready for telecoms usage.

- Not all infrastructure can be combined into a homogenous network. In particular, combining different utility infrastructure may require the duplication of engineering efforts and additional maintenance costs. As a result, OFCOM found that communications providers have a strong preference for ubiquitous telecoms infrastructure, although there is growing interest in using alternative infrastructure in areas where telecoms infrastructure does not reach or is in poor condition.

For reasons such as these, OFCOM concluded that even with access to all competing physical infrastructure, there would be insufficient competitive constraint on the dominant provider of telecoms infrastructure, BT Openreach. Thus, regulation of the SMP provider was required alongside wider Access to Infrastructure Regulations (UKG, 2020) that apply to all infrastructure owners.

7.2 What to mandate and what to leave to negotiation?

Recommending that all access seekers and access providers have an obligation to negotiate infrastructure sharing agreements, and that the terms of those agreements should be transparent, fair and non-discriminatory is a good example of light-touch regulation as there is an inherent obligation, but it is hedged so that there is considerable room for commercial negotiation.

Is this sufficient to achieve economically efficient outcomes? Where the infrastructure owner does not have a position of SMP, it probably is sufficient and (as described above) it may be counter-productive for the regulator to mandate terms and conditions. However, regulators may still have a role to play in resolving disputes and in investigating ex-post should there be concerns about anti-competitive practices.

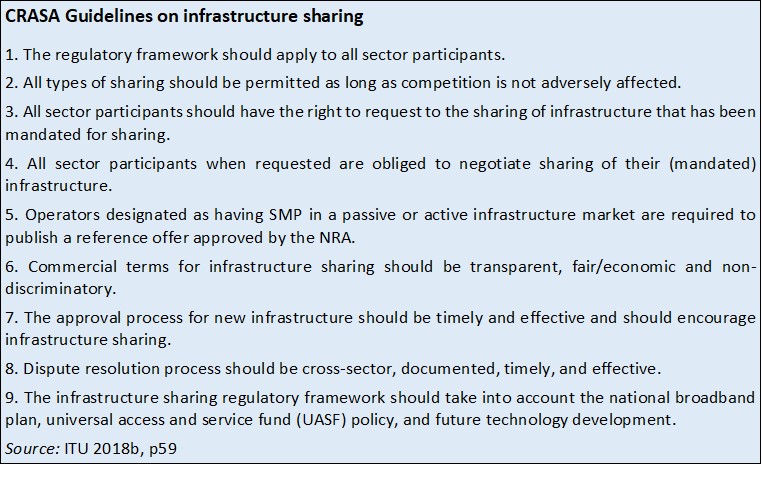

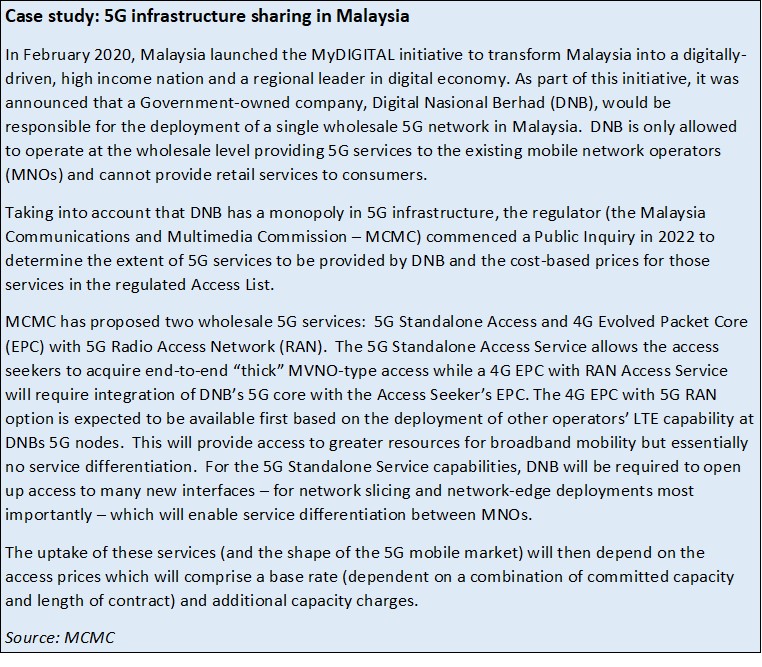

Many countries are moving towards a telecoms industry structure that includes a single major shared communications infrastructure provider: e.g. a national fibre backbone network (e.g. Tanzania) or a national 5G network (e.g. Malaysia – see text box) or a single integrated wholesale provider for all fixed and mobile services (e.g. Brunei Darussalam[4]). In these circumstances regulatory obligations should extend beyond “must negotiate” to include open access rules, justified either because of public funding or/and because of the operator’s SMP status in the market for infrastructure, whether passive or active.

Open access rules should not only guarantee transparent, fair and non-discriminatory access for all interested parties; they also need to establish an appropriate pricing methodology. That means providing a commercial rate of return to the access provider, taking into account the risks of investment already made and incentives to continue investing in the high-capacity networks that will be required in the coming years.

7.3 How to set access prices?

Access pricing principles need to balance the risks, and therefore the allowable rates of return, between the party providing the infrastructure and the party providing the end-user services over that infrastructure. In economic theory this balance will be achieved when prices are set at long-run incremental cost, with a mark-up for efficiently incurred operational costs (LRIC+) and using a weighted average cost of capital (WACC) that accurately reflects the investment risk under current market conditions. However, with large scale infrastructure assets, and particularly with new investments such as fibre or 5G mobile networks, there are considerable uncertainties in both supply and demand that make accurate assessment of efficient LRIC+ prices almost impossible. For these reasons, regulators are best advised to establish pricing principles rather than attempting to establish actual prices. The parties can then be left to negotiate on the basis of the pricing principles, with the regulator intervening only if commercial agreement cannot be reached.

Regulated pricing principles for infrastructure access need to take account of two particular uncertainties:

- The extent of total demand. Broadband infrastructure involves a major up-front investment that needs to be recovered over many years based on the total service demand, typically measured in Megabytes. Prices based on LRIC+ will vary substantially depending on demand forecasts that are inevitably conjectural.

- The variation in demand between different service providers. The same uncertainty in demand forecasting applies to each service provider individually, with the result that each commercial negotiation will have a different dynamic. Some service providers might prefer to pay a single flat rate per MB; others might like volume discounts; yet others may prefer to co-invest in the infrastructure to obtain an indefeasible right of use (IRU) for a certain amount of capacity, which can be topped up if required. The challenge is to meet the needs of each of these different service providers in a manner that is fair and non-discriminatory.

In addressing these issues, regulators need to remember that the primary requirement is to encourage infrastructure investment. This means that the WACC used when setting prices must be sufficiently high to attract investment capital, taking account of the risks involved. Secondly, regulators need to ensure that built capacity is utilised to the fullest extent possible. This means that prices should be set using cost models that consider aggregate demand over the long term and taking accounting of long asset lives for passive infrastructure (e.g. the European Commission recommends lifetimes of a minimum of 40 years for ducts). Such approaches create relatively low prices in the early years of an asset’s lifetime, which generate a rapid increase in demand and fill up infrastructure capacity as fast as possible, which ensures an adequate WACC over the longer term.

Given the uncertainty in demand forecasts, it is important that prices are reviewed on a regular basis and changed as necessary to keep them in line with the regulatory principles. An annual update to cost models and an annual realignment of access prices, especially in the early years of a major network investment, is appropriate.

8 Cross-sectoral infrastructure sharing

Some of the infrastructure required for telecommunications networks may equally be used by companies in other sectors of the economy. This opens up the possibility of cross-sectoral infrastructure sharing. Many of the models and ownership structures described above could equally apply to across sectors (e.g. electricity, rail and road networks). There is the chance of enhancing competition by having other utilities (which often already own and operate communication facilities for their own purposes – e.g. signalling or monitoring) providing telecommunication services usually on a wholesale basis.

Cross-sectoral infrastructure sharing, and the co-ordination of infrastructure investment between utilities is an increasingly important component of the digital economy. Sharing of facilities between sectors can reduce supply bottlenecks in the telecommunications sector in a manner that is more pro-competitive than can be achieved with vertically integrated operators. In the UK, for example, Access to Infrastructure Regulations (UKG, 2020) were set up in 2016 with the aim of reducing the cost of deploying high speed (>30Mbps) electronic communications networks. The Regulations enable sharing of information about access to physical infrastructure (e.g. ducts and poles) across gas, electricity, water, heating, transport and communications sectors and grant the right to access that infrastructure on fair and reasonable terms and conditions.

The World Bank’s toolkit for cross-sector infrastructure sharing (World Bank, 2017) recognises six different business models, which are not mutually exclusive but from a list from which individual commercial agreements may be formed:

- Joint development: infrastructure owners and network operators coordinate in planning and constructing or refurbishing infrastructure. This is the most efficient approach but is only practical where new infrastructure is being developed.

- Hosting: the infrastructure owner acts as a passive landlord, hosting the telecommunications equipment of the network operator.

- Dark fiber: the provision of dark fiber by an infrastructure owner to network operators. This is a low-risk option for the utility and can be attractive for the telecommunications supplier, particularly where leasing is done on a long-term IRU basis.

- Joint venture: commercial telecommunications services are provided by the network operator using facilities provided by the infrastructure owner with profits being shared between the partners based on a commercial agreement.

- Wholesale services: the infrastructure owner develops its own telecommunications services which it supplies to the network operator on a wholesale basis. This offers the utility the opportunity to make greater profits, but it is a higher risk approach and depends on having strong technical and marketing capabilities.

- Ancillary services: the utility may provide services such as co-location, power supply and on-site support alongside some other form of infrastructure sharing.

One study that focused on the electricity sector (Pereira, 57) concluded out that regulators and policymakers should pay more attention to cross-sector infrastructure sharing to create an environment that can incentivize electric utilities and telecommunications operators to work together. The authors point out that for electric utilities (as for other networks) there is negligible marginal cost in installing an extra fibre pair when constructing their infrastructure. The approval of construction requests should therefore be conditional on bearing in mind the potentiality of cross-sector infrastructure sharing in the future, reserving enough space to comply with the sharing standards.

In some municipalities the entire local infrastructure is owned or operated by a single entity (either an arm’s length public company or public-private partnership) so that greater economies of scope may be realised and access to infrastructure is fully co-ordinated to maximise cost savings.

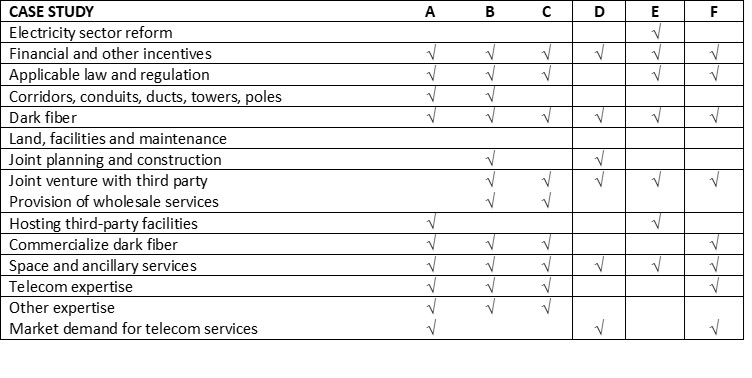

Table 2: Components of selected cross-sector infrastructure sharing initiatives

Case studies:

- Lesotho Electricity Company

- CEC Liquid Telecom (Zambia)

- Baltic Optical Network (Estonia)

- Electricity Supply Corporation of Malawi

- Ghana’s Electricity Transmission Line Fiber

- SOGEM (Mali, Mauritania, Senegal)

Source: Pereira p52

9 Co-investment in new infrastructure

The trend towards joint ventures for infrastructure sharing and cross-sectoral sharing agreements, leads logically to the goal of co-investment for new network infrastructure projects. Co-investment means any investment where ownership or control is shared between two or more parties.

One of the earliest regulatory statements in support of co-investment came from the European Commission in its Next Generation Access Recommendation (EU, 2010). This Recommendation foresaw the need for large-scale investment in fixed broadband infrastructure and at the same time the disincentive that infrastructure sharing regulations impose on potential investors. The EC therefore proposed that under certain conditions co-investment may lead to the most efficient outcomes. Those conditions included:

- Each investor enjoys strictly equivalent and cost-oriented access to the infrastructure

- The co-investors are effectively competing in the downstream market; and

- There is sufficient capacity in ducts for third parties wishing to access the infrastructure.

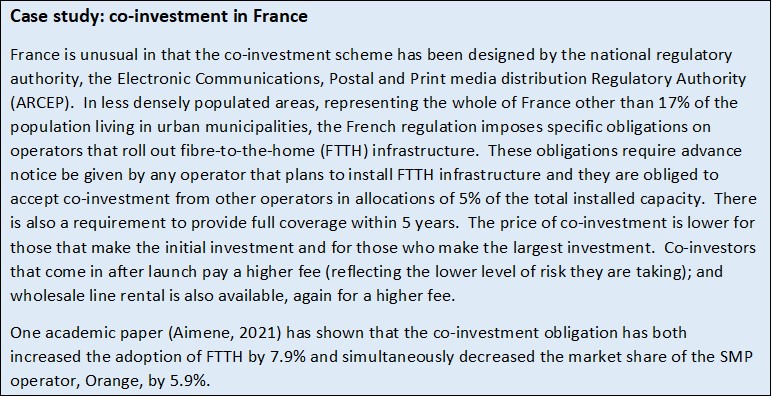

The European Electronic Communications Code (EECC) that was adopted in 2018 (EU, 2018) introduced further provisions in support of investment in very high capacity networks, including an explicit support of the co-investment model. Operators with significant market power offering access to their infrastructure via co-investment can then be exempted from other access obligations[5]. The impact of such an exemption will vary between geographic areas, but in general it will incentivise co-investment and make it harder for potential entrants to cherry-pick co-investment opportunities in low cost (low risk) areas whilst simultaneously relying on regulated access prices in high cost (high risk) areas.

It should be noted that some forms of access regulation remain effective, even under the co-investment model. For example, a requirement to share space in ducts or on mobile towers, can increase the incentive to co-invest, as it is likely to increase demand and consequently the rate of return on investment.

Co-investment is likely to be the model of choice for rolling out the next generation of technology, specifically 5G mobile and full fibre networks. Each of these technologies requires a large-scale investment under conditions of great uncertainty about future demand and consumers’ willingness to pay. Co-investment models allow for the concomitant risks to be shared between all the relevant stakeholders, including network operators and service providers, but potentially also businesses and government agencies.

With 5G in particular, business users in sectors such as healthcare and transport are likely to implement their own connectivity solutions which will require some degree of ownership and control of mobile networks. Various technical solutions are being considered, with “network slicing” allowing a kind of virtual private network to operate on the same infrastructure in parallel with the public mobile service. Co-investment in such a network is likely to be much more commercially attractive than attempting to operate an independent private mobile network. There are also broadly-based public private partnership programs, such as the European 5G PPP project[6], that involve municipalities, businesses and network operators.

A particular challenge for co-investment models of infrastructure sharing is handling requests to participate some time after the initial investment is made. Owing to the high levels of risk involved in these projects, many potential investors will wish to wait and see what happens before committing their financial resources. Such an approach makes commercial sense, but it acts against the common interest and the policy objective of fast infrastructure roll-out. It is therefore necessary to establish pricing conditions that allow for but do not reward delayed investment. A number of theoretical options have been identified (CERRE, p43) involving:

- an increased risk premium (i.e. a higher rate of return) for early investors, or

- a requirement on potential investors to purchase a co-investment option (giving the right to co-invest later in return for a payment when the initial investment is made), or

- a requirement on potential investors to enter into a commitment to buy a minimum capacity once the infrastructure is available.

10 Digital mapping of infrastructure

A co-ordinated approach to infrastructure sharing can only happen once there is a common understanding of existing infrastructure and future development plans. This requires digital mapping of infrastructure assets and cross-sectoral data sharing. It is a major task that requires:

- developing a common framework of definitions, principles and calculation methods

- construction by each infrastructure owner of a digital inventory of network assets using the common framework

- co-ordination of digital asset registers to provide a catalogue that is uses open data principles such as:

- data that is discoverable, searchable and understandable

- standardised metadata, common structures, interfaces and standards

- security and resiliency.

- creation of a digital system map to increase visibility of infrastructure and assets, enable optimisation of investment and inform the creation of new markets.

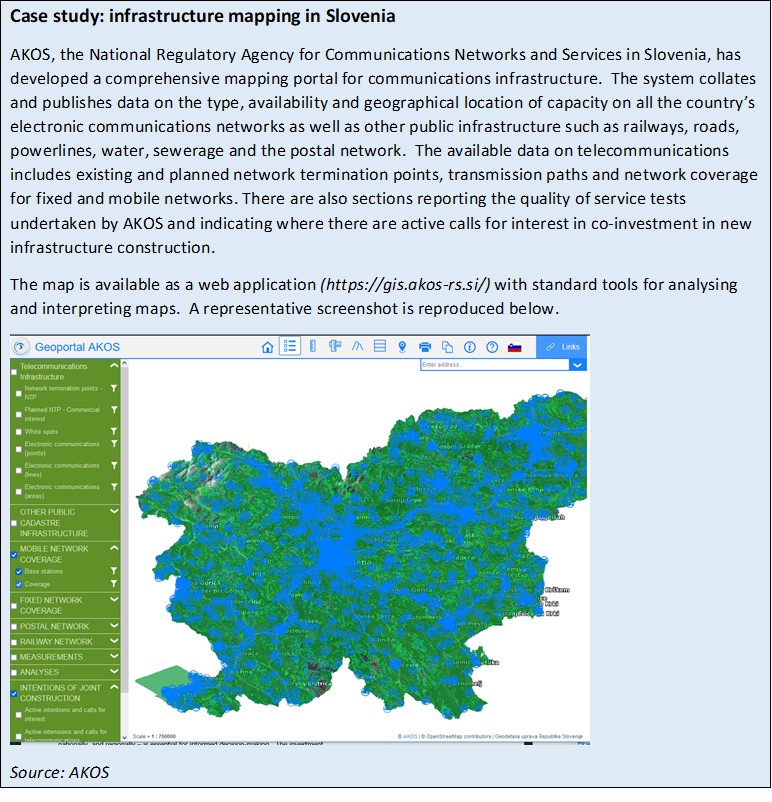

There are good examples of digital mapping taking place by organisations within the telecommunications industry (see AKOS case study below) and within other sectors. However, many of these initiatives fall far short of what is ultimately required. For example, a 2019 report from the UK Regulators Network (UKRN, p10) concluded that:

- The study found that data is already being made available on fairly open terms within sectors, with a shift over recent years towards more open data. However, some sectors are more advanced than others in taking this forward, and despite a range of Government initiatives to promote and facilitate data sharing and drive innovation, data sharing across sectors is limited and often at the stage of initial trials and pilot schemes.

The UKRN report was based on primary research with infrastructure owners and there was widespread agreement amongst respondents on the benefits for broadband deployment that would come from digital mapping and sharing of digital data. These include:

- informed and more appropriate selection of areas for investment

- more effective roll-out of fibre keeping disruption to a minimum (e.g. helping to avoid digging up the same road twice)

- allowing public subsidies and state aid finances to be better allocated to areas with minimal investment

- reducing damage to equipment and infrastructure during civil works.

Despite this awareness of the benefits, there are some significant barriers to data sharing, principally concerning data confidentiality, data quality and liability risks. In these areas regulatory guidance would be invaluable clarifying what data can and should be shared and what data must be kept private. In many organisations there is a culture of concern surrounding data protection regulations which has resulted in blanket bans or convoluted rules and procedures for data sharing.

10.1 International initiatives

The ITU maintains an Infrastructure and Connectivity portal[7] which brings together a wealth of data, reports and other resources related to connectivity and infrastructure development worldwide. Part of this effort has focused on broadband mapping. The ITU’s interactive transmission map[8] overlays different geospatial data and ITU surveys, in particular the data research on terrestrial backbone connectivity. The map displays over 4 million kilometres of global terrestrial networks involving, 44 thousand transmission links and 27 thousand Nodes (or access points to backbone fibres), from nearly 600 operators. These is helping to shape infrastructure strategies to connect underserved or disconnected communities. The results for individual countries can be accessed under “Indicators” tab.

Broadband mapping – whereby regulators assess service availability and quality locally, nationally, and regionally – is essential for informed decision-making. The investment involved means economies of scale that reward collaborative initiatives both across sectors and across regions. Infrastructure mapping systems help to avoid overlapping construction and deployment, increase awareness between regulators and governments at the national level, as well as feeding into regional harmonization initiatives and revealing cross-border collaboration opportunities.

The topic was much discussed at GSR-21 from which the Best Practice Guidelines (ITU, 2021, p7) called upon regulators and policy-makers to:

- Adopt data-driven tools in decision-making (including big data and open data schemes), machine learning tools and online platforms, including national GIS systems to identify white and grey areas and coordinate the deployment and sharing of digital infrastructures, such as national infrastructure mapping systems.

Under the Kigali Action Plan that was developed at the World Telecommunication Development Conference in 2022 (WTDC-22) the mapping of infrastructure was explicitly considered by the Arab and European region in their respective Regional Initiatives.

A recent Broadband Mapping study by the European Commission (EC 2020) showed that, in the absence of a commonly agreed methodology:

- Mapping data is not comparable across the EU and often public authorities lack detailed and reliable data to set policies, to ensure that public funding is compliant with relevant regulation, to programme funds and successfully monitor the execution of these actions at regional, national and European level. This lack of reliable data risks resulting in policy paralysis, in regulatory uncertainty, and poor planning of broadband projects.

It noted that there was no international example that offers a model to follow, and thus proposed that the EU developed its own framework, with a common platform for measuring key quality indicators such as reliability and resilience. The result is the European Broadband Mapping web portal[9] which presents interactive mapping platform showing the quality of internet delivered by broadband networks across Europe and allows registered infrastructure owners to upload and release data about their networks in a standard format.

References

Aimene, Louise, Marc Lebourges and Julienne Liang. 2021. Estimating the impact of co-investment on Fiber to the Home adoption and competition. Paris: Orange SA. https://www.orange.com/sites/orangecom/files/documents/2021-09/Estimating%20the%20impact%20of%20FttH%20coinvestment%20RevsionTP_March%202021.pdf

Arakpogun, Emmanuel Ogiemowonyi; Ziad Elsahn, Richard B. Nyuur; Femi Olan. 2020. Threading the needle of the digital divide in Africa: The barriers and mitigations of infrastructure sharing. London: Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162520310891

BEREC (Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications). 2018. Report on infrastructure sharing. Brussels: BEREC https://www.berec.europa.eu/en/document-categories/berec/reports/berec-report-on-infrastructure-sharing

CERRE (Centre on Regulation in Europe). 2020. Implementing co-investment and network sharing. Brussels: CERRE: https://cerre.eu/publications/telecom-co-investment-network-sharing-study/

EC (European Commission). 2010. Recommendation 2010/572 – 2010/572/EU: Commission Recommendation on regulated access to Next Generation Access Networks (NGA). Brussels: EC https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j4nvk6yhcbpeywk_j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vij17buxpiyc

EC (European Commission). 2020. Broadband Infrastructure Mapping. Brussels: EC https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/rolling-plan-ict-standardisation/broadband-infrastructure-mapping-0

EU (European Union). 2018. Directive establishing the European Electronic Communications Code”, European Union 2018/1972, December 2018. Brussels: EU https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L1972

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2021. Economic policies and methods of determining costs of services related to national telecommunication/ICT networks. Geneva: ITU. https://digitalregulation.org/wp-content/uploads/ITU-D-Question-4-1-Final-Report-2021.pdf

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2021A. Global Symposium for Regulators (GSR) 2021 Best Practice Guidelines. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Conferences/GSR/2021/Documents/GSR-21_Best-Practice-Guidelines_FINAL_E_V2.pdf

OFCOM (Office of the Communications Regulator). 2020. Promoting competition and investment in fibre networks: review of the physical infrastructure and business connectivity markets. London: OFCOM. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/149330/volume-1-pimr-draft-statement.pdf

Pereira, Beloward Edson, SongHee You, Youngjin Kim, Yus Seon Kim. 2021. Infrastructure Sharing Between Electric Utilities and Telecommunications Operators in Developing Countries. Seoul: Yonsei University. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjjw4bKpKX5AhWbS0EAHV9_AnIQFnoECDQQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fipaid.yonsei.ac.kr%2Fipaid%2Fboard%2FPublished.do%3Fmode%3Ddownload%26articleNo%3D36354%26attachNo%3D23779&usg=AOvVaw1mGLfE8xnR1XyNTa3Ju7Hv

UKG (United Kingdom Government). 2020. Review of the Access to Infrastructure Regulations. London: UKG https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-the-access-to-infrastructure-regulations-call-for-evidence/review-of-the-access-to-infrastructure-regulations-call-for-evidence

UKRN (United Kingdom Regulators’ Network). 2019. Infrastructure Data Sharing. London: UKRN https://www.ukrn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/UKRN-Infrastructure-Data-Sharing-0919.pdf

World Bank. 2017. Global Toolkit on Cross-Sector Infrastructure Sharing. Washington DC: World Bank https://ppiaf.org/documents/4709/download

WTDC-22 (World Telecommunication Development Conference 2022). Provisional Final Report. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/md/18/wtdc21/c/D18-WTDC21-C-0103!R1!PDF-E.pdf

Endnotes

- Adapted from https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/infrastructure-sharing ↑

- Arakpogun, p10 ↑

- available here ↑

- For more details see available here ↑

- EU 2018, Article 76 ↑

- See: available here. ↑

- available here ↑

- available here ↑

- available here ↑