The ITU Guidelines on Child Online Protection

21.05.20211 Introduction

The Internet has transformed how we live. It is entirely integrated into the lives of children and young people, making it impossible to consider the digital and physical worlds separately. With 69 per cent of young people online in 2019, and one in three children being connected, the Internet has become an integral part of children’s lives, presenting many possibilities for children and young people to communicate, learn, socialise and play, exposing children to new ideas and more diverse sources of information, opening opportunities for political and civic participation for children to be creative, and contribute to a better society[1].

However, just as children and young people are often at the forefront of adopting and adapting to the new connected technologies together with the opportunities and benefits they bring, they are also being exposed to a range of content, contact, conduct and contract risks online, some of which can translate into potential harms online and offline.

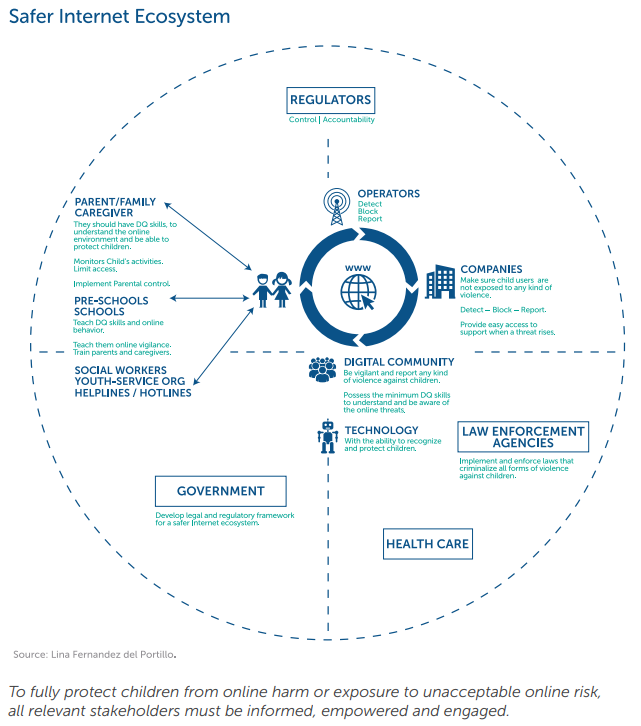

It is important for all relevant stakeholders including policy-makers, industry, parents and educators as well as children themselves to appreciate these risks and potential harms in formulating harmonised prevention and response mechanisms.

Regulatory bodies as stakeholders are highly relevant to the implementation and advancement of frameworks relating to child online protection, as they provide mechanisms of accountability through the monitoring of standards related to children’s rights within ICTs, alongside government institutions.

2 The importance of a regulatory framework for Child Online Protection

Alongside an understanding of the activities and experiences of the various actors and stakeholders on child online protection (COP), it is essential for policy-makers to consider the circumstances and responses from other countries. There have been innovative developments and initiatives in the regulatory and institutional response to threats to children’s safety and wellbeing online.[2] In addition to appreciating what is possible, it also helps policy-makers to challenge existing provision and potential; and identify areas of cross-border collaboration and engagement. A number of these national and international initiatives and developments are signposted in the guidelines for policy-makers.

There are clear benefits from a national child online protection strategy. The development of adequate national legislation, the related legal framework, and within this approach, harmonisation at the international level, are keys steps in protecting children online. These frameworks may be co-regulatory or full regulatory frameworks, as these frameworks provide the most efficacy in terms of incorporating measures to ensure monitoring and compliance, through the adoption of a “safety by design” approach.

These frameworks should address all harms against children in the digital environment, providing a continuum between violence affecting children both online and offline. At the same time, this should not unduly restrict children’s rights. These frameworks should specifically cover the sexual exploitation of children online (including child sexual abuse material), national education provision, and expectations for industry providers.

Governments should create a clear and predictable legal and regulatory environment which supports businesses and other third parties to meet their responsibilities to safeguard children’s rights throughout their operations, at home and abroad.

In this context, regulators are best positioned to contribute to the role of controller and accountant in collaboration with the government institutions. This might include media and data protection regulators.

It is recommended that governments strengthen regulatory agency responsibility for the development of standards relevant to children’s rights and ICTs. Regulatory bodies should be strengthened by giving them the legal authority and resources needed to respond to or investigate concerns. In doing so, regulatory bodies will be able to effectively enforce organisations to provide redress in instances where child online safety has been compromised. This is especially important because other remedies available to those adversely affected by corporate action – such as civil proceedings and other judicial redress – are often cumbersome and expensive.

In some countries the Internet is governed by a framework of self-regulation or co-regulation. However, some countries are considering, or have implemented, legal and regulatory frameworks, including obligations for companies to detect, block and/or remove harm against children from platforms or services, as well as to provide clear reporting routes and access to support.

Regulators need to define clearly certain child protection online objectives and challenges, with reference to national research and evidence. Given the rapidly evolving context of child online safety, it is important that evidence-based regulatory frameworks are being implemented, and are being reviewed in a period manner. Regulators need to put in place a clear review process and methodology for assessing the effectiveness of frameworks of co-regulation, and in the event that co-regulation fails to address the identified challenges, initiate a formal legislative process to address those challenges.

Successful measures utilised within co-regulatory frameworks could gradually be adopted within a legislative process, becoming formal law. This process would allow for these measures to become legal backstops, preventing “roll-back” or the termination of adherence to these measures.

Regulators may consider, where not yet integrated in the COP system, to provide a Helpline, coordinated with INHOPE, the International Association of Internet Hotlines. These hotlines notify Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to remove inappropriate content and report the specific case to law enforcement agencies, for victim identification and response.

Regulators should have the capacity and resources to conduct independent measurements and studies to assess how platforms report and deal with issues concerned with child protection. Technology exists for regulators to independently monitor platforms. Industry providers should be supported to publish the required transparency reports.

An example of the importance of regulators in the context of COP is cyberbullying:

Internal remedial and grievance mechanisms are often ineffective in the case of cyberbullying, although the content is distressing and harmful, it is often not addressed by national legislation and there is no clear basis for seeking its removal by the content host. Empowering a public authority to receive complaints regarding cases of cyberbullying and to intercede with content hosts to have the relevant material removed would be an important safeguard for children providing a rapid response and a clear legal basis for addressing the removal of cyberbullying material.

3 What is child online protection?

Child online protection (COP), is the holistic approach to respond to all potential risks and harms children and young people may encounter online.[3] Impacts range from threads to protection of personal data and privacy, to harassment and cyber bullying, harmful online content, grooming for sexual purposes, and sexual abuse and exploitation. Different risks may need different approaches within a holistic framework; and a balance between the different rights of the child, including protection and participation. It is everyone’s responsibility to protect children from the harms that online risks may cause.

Child online protection is a global challenge. Due to the rapid advancements in technology and society, and the borderless nature of the Internet, child online protection needs to be agile and adaptive to be effective.

Through this approach, it is possible to build safe, gender-sensitive, age appropriate, inclusive and rights respecting digital environments for children and young people. The approach is characterised by:

• a child rights-based approach, upholding the rights and the responsibilities of the state and the individual to respect children’s rights as enshrined in the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child, 1989, and other international and regional human rights instruments;

• a dynamic balance between ensuring protection and providing opportunity for children to be “digital citizens”, understood as an individual who has the appropriate skills and knowledge to use the internet in a responsible manner;

• prevention of harm;

• response and support in the face of threats, including provision of access to support systems as well as the ability to self-help in the face of certain risks through digital literacy and resilience.

This approach furthermore incorporates child participation in the design, implementation and evaluation of the solutions to keep children safe online.

4 The ITU Guidelines on Child Online Protection

For more information, this section includes an overview of the ITU Guidelines on Child Online Protection. These Guidelines have been developed by a working group of more than 50 organisation experts in the field of ICTs and child rights and consist in a comprehensive set of recommendations for all relevant stakeholders on how to contribute to the development of a safe and empowering online environment for children and young people.

Four sets of Guidelines provide guidance on COP for children, parents and educators, industry and policy-makers:

Children

The 2020 Guidelines on COP for children have been developed in a child friendly format. Adapted to different age groups, the resources create an opportunity to learn about and strengthen young people’s digital skills and knowledge, helping them learn ways to manage online risks, while at the same time empowering them to exercise their rights online and engage in opportunities that the internet presents to them. The new resources depict Sango[4] , the Child Online Protection mascot, as the main character.

Parents and Educators

For parents, carers, guardians and educators, the guidelines aim to sensitize families to the risks and potential harms and help cultivate a healthy and empowering online environment at home and in the classroom. The Guidelines highlight key recommendations for parents and educators and emphasize the importance of open communication and ongoing dialogue with children, creating a safe space where young Internet users feel empowered to raise concerns.

Industry

The recommendations for different types of ICT industry focus on protecting children in all areas and against all risks of the digital world and as such, highlight good practice of industry stakeholders that can be considered in the process of drafting, developing and managing businesses child online protection policies. Guidance is provided to industry stakeholders on implementing ‘child rights by design’ approaches including safety-be-design and privacy-by-design models. Having a major responsibility not only to help promote awareness of the online and safety agenda to the wider community and to provide a channel of participation and engagement for young people, but even by offering safe and secure online experiences throughout their services, industry plays a key role possessing the technological knowledge that policy-makers need to address and understand in order to develop sustainable and effective COP strategies.

Policy-makers

The Guidelines for policy-makers on child online protection propose concrete recommendations on developing a national strategy on COP, provide tools to identify key stakeholders to engage with and coordinate efforts as well as alignment with existing national frameworks and strategy plans. A multi-stakeholder approach allows for policy responses integrating areas of expertise ranging from divisions focused on law, to digital technologies, and child rights and child protection, allocating to each stakeholder the appropriate accountabilities.

In order to effectively prevent and respond to online risks and harms for children, such an inclusive multi-stakeholder national child online protection strategy that integrates and references existing frameworks provides the necessary roadmap to the global challenge of child online protection.

The strategic development of policies in relations to child online protection should be revisited and reviewed in a periodic manner, in response to the changes in the digital environment.

Governments, the ICT industry and civil society need to work with children and young people to understand their perspectives and spark genuine public debate about risks and opportunities. Supporting children and young people to manage online risks can be effective, but governments must also ensure that there are adequate support services for those who experience harm online, and that children are aware of how to access those services.

Child Online Safety: Minimizing the risk of violence, abuse and exploitation online

Endemic online child exploitation and abuse is preventable, but it requires that we all commit to protect children as they access the Internet. We must work together to empower children across all tiers and lifestyles to gain the benefits of connectivity while avoiding or mitigating the connectivity-related risks they face today. The Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development’s Working Group 2019 Report on Child Online Safety: Minimizing the risk of violence, abuse and exploitation online recognizes that individual and collective actions are required to achieve our goals.

Many of the tools needed to act against the scourge of violence, exploitation, and abuse of children online exist. But too often, the work that goes into creating them in one jurisdiction is not shared in another. The time and resources spent in the duplication of efforts could have been used in detection and enforcement, or some other area of online child protection. This is why it is urgent that countries and relevant stakeholders cooperate. They need to:

• Incorporate the rights of the child into national broadband strategy and all other relevant areas of national policy.

• Cooperate across borders to create internationally valid standards and terminology for defining and measuring the state of children’s rights and protection online.

• Ensure products and services designed for children by public or private sector, or an NGO have children’s rights at the heart of their operating principles.

• Work with private-sector, civil society, subject matter experts and partners in developing online children’s rights standards for our respective jurisdictions.

• Develop ways to engage relevant local stakeholders in campaigns against harms such as child exploitation and other online children’s rights issues.

• Use new and innovative technologies such as AI, data analytics, and data motifs, to prevent networks and services from being used by offenders.

• Make measurable progress toward blocking upload of CSAM and other non-sexual child-abuse or child-harm material in the services and products under our respective jurisdictions.

• Commit our organizations to cooperating cross-border with relevant partners to detect, stop, and, where possible, prevent harm to children online.

To help mobilize all the actors in child online safety space, the WG developed a Child Online Safety Universal Declaration. Building on the recommendations of the report, the declaration is an expression of our commitment to children and their wellbeing. The purpose of the Declaration is to help mobilize relevant stakeholders, such as technology companies and regulators in a position to directly or indirectly contribute to improving children’s safety online.

The declaration is available at: https://www.broadbandcommission. org/Documents/working-groups/ ChildOnlineSafety_Declaration.pdf

Source: Extracted from the Child Online Safety: Minimizing the risk of violence, abuse and exploitation Report 2019, produced by the Broadband Commission’s Working Group on Child online safety.

- UNICEF. 2020. Digital civic engagement by young peopleUNICEF. 2020. Pandemic participation: youth activism online in the COVID-19 crisis

Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Violence against Children. 2021. Children as agents of positive change ↑

- Selected examples:Self-regulation: Highlighted as one of the key instruments of the European Strategy of the European Commission to create a better Internet for children.

Full regulation: In Australia online regulation is overseen by the e-Safety Commissioner, who has been empowered under the Enhancing Online Safety Act 2015. ↑

- A child is any person under the age of 18 following the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) whereas the term “young people” defines any person between the ages of 15 and 24. Both terms are used here for reasons of inclusiveness. ↑

- Sango is the Child Online Protection Mascot which was created by an energetic and motivated group of children on the occasion of the Futurecasters Global Young Visionaries Summit, which was hosted and co-organized by ITU and the Model UN programme of Ferney-Voltaire, France (Geneva, 8-10 January 2020) ↑