Guiding principles for ICT regulators to enhance cyber resilience

05.02.2024Introduction[1]

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) enable global digital connections between individuals, businesses, government, academia, and civil society. ICTs play a fundamental role in all aspects of national security and economic and social affairs[2]. In a world where modern societies are increasingly digital and hyperconnected, it is essential for the communication and technological infrastructures on which they depend to be fully functional and resilient against cyber incidents/attacks[3].

Telecommunications/ICT regulators, hereafter “ICT regulators”, can have sector-specific, multi-sector, or converged institutional structures. Their mandates and roles may have also shifted from being rules-based to principles-based.[4] Though their institutional structures, roles, mandates, and responsibilities vary by country, ICT regulators play a crucial role in strengthening cyber infrastructure resilience and promoting online safety. They must understand emerging cybersecurity challenges and collaborate with stakeholders to develop policies and regulations that help build trust in cyberspace, and in the use of digital technologies, services, and products.

To guide ICT regulators in these tasks, this article describes the cybersecurity challenges that require attention from a policy and regulatory perspective. Although the article primarily targets high-level executives in telecommunications/ICT regulatory bodies, it is also intended to address the broader public interested in telecommunications/ICTs and cybersecurity. The article emphasizes the crucial role of ICT regulators in coordinating stakeholders and adopting a collaborative approach to align cybersecurity regulation with other policy goals and provides guiding principles for ICT regulators to improve cybersecurity resilience.

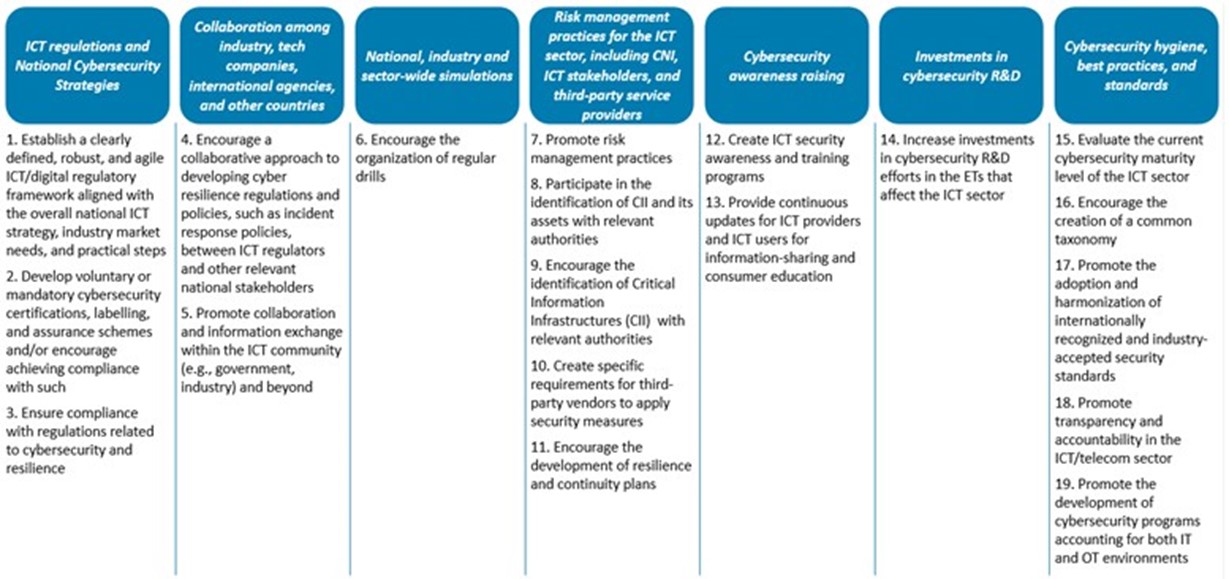

Figure 1 Guiding principles[5]

The article concludes by providing nineteen guiding principles for ICT regulators, grouped under seven categories and resumed in Figure 1.

Section 1: Defining the ICT Cybersecurity Context

1.1: ICT infrastructure and digital services: Why resilience matters in a digital economy and society

The ICT sector faces numerous cybersecurity challenges due to increased access to and reliance on the Internet and digital technologies. Cyber incidents in the ICT sector represent a global challenge because of their intrinsic cross-border nature. Given that developing countries, are frequently insufficiently prepared to address cybersecurity challenges due to a lack of resources and policy frameworks, among other factors, and that they will be the countries with the greatest number of new Internet users over the next decade, outlining and addressing the main threats and vulnerabilities is critical.[6] Identifying and assessing cyber threats and vulnerabilities within the ICT sector is particularly difficult due to its dynamic and complex environment.[7]

Critical Infrastructure (CI) or Critical National Infrastructure (CNI), hereafter “CNI”, enables services, such as telecommunications, energy supply, and drinking water, and is defined as an essential infrastructure for preserving vital functions, the disruption of which will cause serious repercussions. Critical Information Infrastructure (CII) includes critical information and communication infrastructures and systems and could be a standalone CNI (e.g., information and telecommunication CNI) but it can also be part of another CNI (e.g., CII, such as process control systems that monitor and control the generation of electrical power within a CNI, such as energy).[8] Thus, there are numerous interdependencies between CNIs and CIIs that increase the exposure to cybersecurity risks. To achieve cyber resilience, ICT regulators and service providers can participate in creating adequate measures for preparedness and response, minimizing impact and operational disruptions.

1.2: Challenges

The borderless nature of cyber risks, the lack of harmonization across different jurisdictions, the rapid development of emerging technologies (ET), different data and privacy protection frameworks, the liability of ICT companies, and the interoperability of their products complicate the challenges faced. These challenges, coupled with those linked to the widening cyber workforce gap, could be considered by ICT regulators to contribute to the strengthening of national cyber resilience.

Ever-increasing complexity of ICT supply chains and digital supply chains

A challenge in the ICT environment is the growing complexity of ICT supply chains[9] since they are reliant on a broad spectrum of entities and complicated to secure due to the possibility to exploit vulnerabilities at any stage of the product life cycle (design, development and production, distribution, acquisition and deployment, maintenance, and disposal).[10] Moreover, digital supply chains progressively lead to the replacement of traditional supply chains. A digital supply chain can also be called a Digital Supply Network (DSN) that is continuously functioning and characterized by its ability to centrally connect information from suppliers, partners, customers, and other network nodes and flows.[11] Dependence on ICT products and services, reliance on external operators for digital services and assets provision, market concentration around operators, such as DNS and cloud providers, all cause an increase in cybersecurity concerns.

In certain regions, like North America, digital supply chains have become a prominent trend due to investments in ET that are driving market growth. The digitalization of supply chains acts as an emerging trend for other geographical areas (e.g., Asia-Pacific) where strong economic growth has been incentivizing heavy investments in the digital supply chain market.[12] Digital supply chains use advanced technologies to integrate supply chain management functions, allow data to be shared among internal and external stakeholders, provide relevant real-time insights into functional performance and end-user demand, and sustain a more informed relationship among stakeholders along the chain.[13] However, these features expose digital supply chains to enhanced risks vis-a-vis traditional supply chains.

Sector interdependencies posing risk of vulnerable attack surface and cascading impacts

ICTs can be a CNI on their own or a cross-CNI sector component since they support various CNI sectors to operate effectively, creating interdependencies between the ICT sector and other sectors, such as energy, finance, and water supply. Thus, the ICT component in CNIs, is essential for the maintenance of vital societal functions, and is referred to as CII.[14] The inter-sectoral reliance heightens the potential impact and cascading effects of a cyberattack. It can also enhance opportunities for malicious cyber activity by increasing the number of possible access points to assets in all involved sectors.[15]

This can create significant national security concerns. Indeed, researchers have found that malicious cyber activity against CNI could have cascading effects on other inter-dependent CNIs, potentially resulting in a severe crisis with the potential for negative spill-over effects across regional and international borders.[16] This interdependence can be illustrated by intelligent electricity networks, such as remote metering, used for improved demand management, and electricity networks that may be employed for information transmission.[17] By using the same technologies, the two sectors not only share the same vulnerabilities inherent to the technological components but are also exposed to vulnerabilities inherent to the other sector, thereby increasing cybersecurity risks and opportunities for successful cyberattacks.[18]

IT and OT convergence urging reconsideration of cybersecurity risk management

While IT and OT systems have traditionally been separated, digital transformation has increased the need for enhanced levels of collaboration for protection of IT and OT.[19] The convergence of IT and OT has led to the need of applying cybersecurity in a similar way for both systems, especially with OT systems becoming increasingly connected to the Internet and no longer being isolated so that security by obscurity could provide efficient protection. This can cause compromise of OT domains (e.g., ICS disruptions due to the delayed flow of information, unauthorized changes, and delivery of inaccurate information)[20] and expand the attack surface of interconnected systems.[21] Within the context of CNIs progressively depending on IT and OT systems,[22] the improper cybersecurity risk management due to convergence can prevent CNIs from functioning safely.

Lack of a common taxonomy

Given the complexity and variety of features, topics, and threats that characterize cyberspace and the ICT sector, the lack of a common taxonomy risks creating confusion and misunderstanding among ICT stakeholders. A shared taxonomy can support ICT operators and service providers in navigating the defining features of cybersecurity, ultimately facilitating communication and information sharing. In this sense, the Taxonomy of Malicious ICT Incidents[23] published by the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), the NIST Glossary,[24] the Cybersecurity Taxonomy[25] issued by the EU Commission, and the Threat Taxonomy[26] issued by ENISA can foster a common understanding of cyber-related terms, issues, and threats and thereby encourage cooperation among interested stakeholders. Establishing a taxonomy that clarifies the difference between essential cybersecurity terms is important for organizing information so that stakeholders understand exactly what they are referring to. For example, the term “threat” in the NIST Glossary is defined as any circumstance or event that has the potential to harm organizational operations, assets, or persons via an information system by unauthorized access, destruction, disclosure, alteration, and/or denial of service.[27] The term “incident” is used in the UNIDIR taxonomy to refer to a larger understanding of a harmful ICT event, whereas the term “act” refers to the direct penetration or hacking of a system or network. National ICT regulators might determine how to encourage the creation of a common taxonomy for their sector while considering nationally and internationally pertinent and recognized categorizations to ensure consistency.

Response to cybercrime and legal harmonization

ICT regulators face several additional challenges, particularly due to using ICTs as a tool or a target for criminal activity,[28] as well as divergences between countries regarding cybercrime laws.

On the one hand, cybercriminals increasingly engage in activities through which they can obtain profit, such as, for instance, Business Email Compromise (BEC). This transnational cybercrime does not require advanced technical knowledge, however, it can lead to significant financial losses.[29] In 2021, approximately 20,000 BEC reports have been received by the Internet Compliant Center (IC3) in the United States, with adjusted losses of about USD 2.4 billion.[30] On the other hand, insufficient or different cybercrime-related laws across countries and the difficulties deriving from the attribution of attacks, pose constraints to defining, prosecuting, and preventing cybercrime. For example, because the Philippines did not have a cybercrime law at the time of the occurrence, the author and distributor of the “LOVE BUG” computer virus, a resident of the Philippines, was not subject to prosecution even though the virus’ spread had significant global negative financial impacts.[31]

ICTs’ cybersecurity depends closely on the proper response to cybercrime. ICT regulators’ mandates may allow them to take measures related to the contribution to enacting appropriate laws. In addition, the transnational nature of cybercrime requires international cooperation for legal harmonization and developing ICT cybersecurity best practices with regards to cybercrime, for which ICT regulators may make an influence.

1.3: Main ICT assets, risks, and vulnerabilities

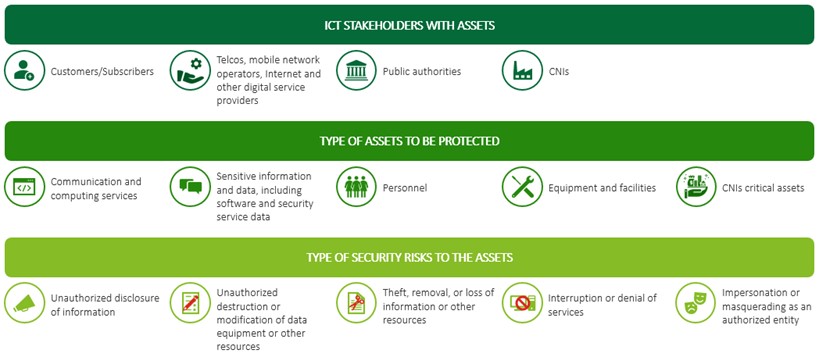

The ICT sector provides key services to society, making it a high-value target for malicious actors and enhancing the need to implement sufficient security measures to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. To implement sufficient security measures, it is critical to perform risk assessment to identify: (1) ICT stakeholders for whom assets need to be protected; (2) ICT assets that need to be protected; and finally outline (3) potential security risks that might negatively impact the assets (see Figure 2).[32] In this environment, ICT regulators working within the scope of their national mandates must also account for international dependencies in terms of physical and digital assets, supply chains, data flows, and transnational cyber threat activities to be addressed via collaboration with other ICT regulators, international organizations, law enforcement entities, industry organizations, service providers, and other international stakeholders.

Figure 2: ICT Stakeholders, Assets and Security Risks[33]

Considering the main types of threat actors (cybercriminal groups, hacktivists) as well as insider threats, common types of malicious cyber campaigns against ICT-related targets can include, but are not limited to, espionage campaigns, ransomware attacks, data theft, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks[34], and RDDoS, to persuade victims to pay a requested amount of money to stop an on-going attack. Furthermore, the ICT sector can also represent an indirect target and/or a potential point of entry to another main victim by exploiting third-party dependencies and supply chain vulnerabilities. Indeed, third-party vulnerabilities and interdependencies across sectors and systems (e.g., IT and OT convergence) can facilitate or enable malicious cyber activity by exploiting unsecured authorized access.[35]

Government departments, regulators, as well as telecom providers are increasingly at risk of these types of attacks. For example, the U.S. Commerce Department’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), charged with policymaking responsibilities vis-a-vis the Internet and telecommunications, was one of the victims of the supply-chain SolarWinds attack in 2020.[36] In 2022, Costa Rica suffered a ransomware attack, which affected 27 public institutions, including the Ministry of Science, Innovation, Technology and Telecommunications (MICITT) and the state internet service provider RACSA. The Conti Group assumed responsibility for the initial wave of attacks and demanded a ransom in exchange for not disclosing information related to residents’ tax returns and critical information on Costa Rican companies taken from the Ministry of Finance, also victim of the attack. The attack resulted in multiple disruptions, such as the temporary shutdown of computer systems used to declare taxes.[37]

ICT vulnerabilities and emerging technologies

Previous work carried out by ITU has identified four general types of vulnerabilities for ICT assets that encompass errors and/or oversights in the effectiveness, design, implementation, or usage of a given protocol or standard. More details on this can be found in Table 1.

| Type of Vulnerability | Description |

| Threat Model Vulnerabilities | Threat Model Vulnerabilities result from the inability to anticipate potential future attacks and threats. |

| Design and Specification Vulnerabilities | Design and Specification Vulnerabilities result from mistakes or oversights in the design of a system or protocol, making it inherently vulnerable. |

| Implementation Vulnerabilities | Implementation Vulnerabilities originate from mistakes or oversights during the implementation of systems or protocols. |

| Operation and Configuration Vulnerabilities | Operation and Configuration Vulnerabilities result from poor or inadequate deployment rules and procedures, or an improper use of options during implementations. |

Table 1: Types of Vulnerabilities[38]

The development of ETs, such as, among others, 5G, IoT, and cloud computing, exacerbates these types of vulnerabilities.

5G technology wirelessly connects mobile devices and other 5G-enabled sensors, machines, and appliances in a faster and more powerful way than previous generations.[39] However, the introduction of untrusted components into a 5G network raises the possibility of serious security breaches affecting the availability, confidentiality, and integrity of 5G data.[40] Working together with academia, associations, and non-profit organizations on R&D projects they conduct can contribute greatly to the security and resilience of 5G. Their subject matter expertise in the domain allows for the analysis, design, testing, and safe implementation of the technology.[41]

Regarding IoT, the ITU defines it as “a global infrastructure for the information society, enabling advanced services by interconnecting (physical and virtual) things based on existing and evolving interoperable information and communication technologies.”[42] While it can be extremely useful in developing smart cities, IoT presents challenges in terms of security, such as the numerous nodes in their system, each being a potential access point facilitating the propagation of harm across the network.[43] India has been one of the countries to issue an IoT policy that specifically includes an R&D and innovation pillar that aims to provide funding for IoT R&D for applications that benefit society. In addition, the pillar planned the launch of an international collaboration initiative to encourage private sector investment in IoT-related R&D and to carry out IoT-related R&D projects with international partners.[44]

Finally, cloud computing can be defined as self-service provisioning and administration on-demand, allowing network access to a scalable and elastic pool of shared physical or virtual resources such as servers, operating systems, networks, software, applications, and storage devices.[45] While cloud technology provides many benefits, such as scalability, flexibility, and potential cost savings, a broad approach to security is required to address the threats that can be linked to some of the main vulnerabilities of the technology, given its features, capabilities, range of services, and deployment models.[46] Research and innovation stakeholders have indicated the significance of zero-trust architectures, the use of privacy-enhancing technologies, and the role that cloud computing plays in 5G, quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and other areas, making these subjects prime candidates for further R&D.[47]

Section 2: Mapping the Cybersecurity Ecosystem

2.1: Cybersecurity stakeholders and roles

Throughout the last decade, governments have significantly increased their efforts to ensure and enhance security and resilience in cyberspace. Various national and global stakeholders compose the cybersecurity landscape, and their identification is crucial to understand their roles and responsibilities within the cybersecurity ecosystem.

Given the interdependencies of ICT infrastructures and services with non-traditional ICT sectors, the large attack surface of these infrastructures, which is frequently targeted by malicious activities, and the benefits that the ICT sector cyber resilience practices can offer to the whole digital ecosystem, ICT regulators become integral to understanding and facilitating cooperation among various stakeholders at the governmental level, with the private sector, and academia to best engender cooperation.

Entities mandated with cybersecurity responsibilities (e.g., national cybersecurity agencies) are generally in charge of implementing national cybersecurity policies, developing best practices, and the country’s overall national cybersecurity strategy. Such documents should be based on multi-stakeholder consultation and collaboration. To achieve this, ICT regulators and entities with cybersecurity responsibilities should collaborate closely to increase national cyber resilience within their respective mandates. Furthermore, regardless of how the mandate, the national cybersecurity landscape alter, and the agencies mandated with cybersecurity responsibilities exercise them, ICT regulators will have their own role with regards to cybersecurity.

Other national sectoral regulatory agencies (e.g., energy, finance, transport and health) should be accounted for when considering the national cybersecurity ecosystem. Regulatory agencies governing such sectors cannot underestimate the impact of cybersecurity on their industries, and collaboration mechanisms with ICT regulators and entities with cybersecurity responsibilities are needed to identify vulnerabilities and flaws and define shared mechanisms to enforce comprehensive and effective cybersecurity policies.

Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs), also known as Computer Incident Response Teams (CIRTs) and Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), are national points of contact “assigned to identify, protect and handle cybersecurity incidents, including additional responsibilities, from detection to analysis, and even hands-on fixing, as well as different situational awareness, knowledge transfer and vulnerability management activities.”[48] They are composed of technical professionals responsible for all the phases of an incident response lifecycle, starting with preparation, detection and analysis, containment and recovery, and ending with post-incident recovery.[49] Some countries have established a sectoral CSIRT, managing incidents affecting ICT service providers. Nevertheless, ICT regulators and service providers also need to communicate cyber incidents to national CSIRTs to ensure coordination and effective information sharing among national stakeholders to increase awareness of cyberattacks targeting the strategic ICT sector and respond to cyber incidents to minimize the damage.

Law enforcement agencies play a critical role[50] in providing over lawful responses to cybercriminal activities. Although attributing cyberattacks to responsible malicious actors is challenging, especially in a cross-border context, law enforcement agencies and other national cybersecurity stakeholders must establish collaboration mechanisms to deter and respond to malicious cyber activities more effectively. ICT regulators and national cybersecurity agencies should develop mechanisms to facilitate collaboration and exchange of information about malicious cyber activities, enable engagement in relevant discussions, and accommodate the requests of law enforcement agencies for the ICT sector. Furthermore, cooperation between ICT regulators and law enforcement agencies can also have a positive impact on end-user safety. Although developing legislation does not fall under the direct responsibility of ICT regulators, coordination and consultation with competent authorities to facilitate the adoption and implementation of cybercrime legislation capable of ensuring adequate responses to cybercrime could have a positive impact on end-users. From its end, the ITU has already co-developed with the United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime (UNODC) a set of toolkits and initiatives[51] addressing legal aspects of cybersecurity, such as the “Combatting Cybercrime toolkit”, which aims to engender a safe, secure, and equitable internet.[52]

Finally, regional and global ICT industry organizations make important contributions to the cybersecurity ecosystem. For example, GSMA, a global organization representing mobile operators and organizations across the mobile ecosystem and adjacent industries,[53] established the Fraud and Security Group (FASG) working group to provide guidance to industry’s stakeholders in managing fraud and security issues threatening mobile operator technologies and infrastructures, as well as customer identity, security, and privacy.[54] To do so, GSMA established a mechanism that encourages the timely and responsible sharing of fraud, security intelligence and incident details, helping to promote a cooperative environment. ICT regulators can gather data from these working groups and use it to adjust national regulatory landscape requirements in light of relevant findings. By encouraging ICT industries to exchange knowledge and ideas with such working groups, ICT regulators may also foster interest and participation in them.

Cooperation mechanisms among national entities are crucial to increase national cyber resilience. The Spanish INCIBE-CERT – which is operated by the Spanish National Cybersecurity Institute (INCIBE), under the Ministry of Economy Affairs and Digital Transformation and through the Secretary of State for Digitalization and Artificial Intelligence – coordinates with other national and incident response teams to facilitate multi-stakeholder responses to cybercrimes involving networks and information systems. When INCIBE-CERT faces an incident targeting critical private sector operators, it operates together with the Cybersecurity Coordination Office of the Ministry of the Interior[55] to orchestrate a coordinated response.

Figure 3: National and global stakeholders operating in cyberspace[56]

2.2: Defining the roles and responsibilities of the ICT regulator

The role of ICT regulators has evolved as it has become more prominent in shaping ICT policy. The scope of the regulations and the mandate have both expanded to embrace a national objective, representative of different ICT stakeholders’ interests.[57] Thus, ICT regulators’ roles and responsibilities may significantly vary from one country to another, reflecting also the different national priorities and stakeholder requirements.

To support national cyber resilience in accordance with their evolving roles and responsibilities, regulators may have to go beyond a limited focus on the basic requirements for strengthening the cyber resilience of communication networks and services. They may instead proactively encourage service providers and ICT-related stakeholders to implement collaborative mechanisms to increase coordination, resilience, and preparedness to respond to malicious cyber activities, as well as promote cybersecurity awareness campaigns.

In addition to possibly having a role to increase awareness on the cybersecurity incidents targeting the ICT sector and participate in the development of proper cybersecurity governance to strengthen the resilience of ICT stakeholders, ICT regulators may have several key functions related to cybersecurity and the protection of the whole ICT supply chain[58]:

- Developing regulations, policies, guidelines, and standards related to new technologies

- Contributing to the identification of Critical Information Infrastructures (CII)

- Supporting risk assessment and management: essential components

- Implementing awareness campaigns

- Improving cybersecurity of ICT products through assurance practices

Developing regulations, policies, guidelines, and standards related to new technologies

To effectively navigate and address the diverse range of cybersecurity-related challenges and enhance the sector’s cyber resilience, ICT regulators should promote the adoption of practices that increase the cybersecurity level of the country’s ICT sector. The Singaporean Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), for example, is involved in the development of standards and guidelines related to, among others, cloud security and cloud outage incident response, and IoT cybersecurity and best practices.[59] Such standards are developed through collaborative efforts involving government agencies, tertiary institutions, professional bodies, and representatives of the information and communication industry, with IMDA playing a central role in informing and coordinating such efforts.

ICT regulators could also contribute to addressing some issues posed by ETs by promoting the adoption of international or national standards. A review of the standards (current, future, proposed, in drafting phase, and under discussion) pertaining to AI cybersecurity, in this instance, linked to ICTs, can help evaluate the standards’ coverage and pinpoint any gaps. Any gaps would indicate whether further regulation is necessary to be adopted or created.[60]

Contributing to the identification of Critical Information Infrastructures (CII)

In order to enable ICT stakeholders and service providers to define CII, it is important for ICT regulators to contribute to the provision of national guidelines and best practices regarding CII identification.[61] CII governance can be organized in different ways depending on the ICT regulators’ mandate and how CII is considered (e.g., horizontally, focusing on interdependencies, vertically, focusing on sectors, sub-sectors, etc., or as a standalone CNI). Based on this, together with national cybersecurity agencies and other relevant stakeholders, ICT regulators could encourage the assessment and listing of critical services as well as their interdependencies according to pre-defined and common criteria. Even though the identification of CII cannot be performed solely by ICT regulators, their knowledge of the sector and linkages with ICT operators and service providers can be leveraged to develop a comprehensive identification of CII.

Identifying CII helps ICT sector stakeholders focus their efforts on preventing damage from malicious cyber activities and increasing awareness about cyber-related threats. Additionally, it enables stakeholders to identify and isolate potential points of failure and cross-sectoral interdependencies across sectors within CII. Because attacks targeting ICT facilities and services can lead to severe consequences for multiple stakeholders, single points of failure might pose a threat to a considerable range of regional or national services. Having a clear understanding of CII, prioritizing research, and analyzing single points of failure among CII can facilitate prompt identification and mitigation. Finally, the development of clear guidelines to recognize CII by ICT regulators can assist service providers to take actions to strengthen cyber resilience, such as prioritizing investments in certain CIIs.

| Identifying CII Assets and Services(i) identifying critical national sectors according to governmental guidelines (e.g., frequently those whose assets, networks, and systems—virtual or physical—are thought to be so essential to the nation that their loss or limitation would severely impair public health or safety, national security, or any combination of these[62]), (ii) identifying critical services and applications within these sectors (e.g., using a state- or operator-driven approach, assessing the criticality, considering inter-sector and cross-border dependencies), and (iii) identifying and classifying CII network assets and services supporting critical services (i.e., assessing business process criticality, identifying critical applications, identifying CII enabling critical applications).[63] |

Supporting risk assessment and management: essential components

A thorough risk assessment is crucial for any organization to clearly understand the main cyber and non-cyber risks their businesses face and set up remediation plans and business continuity measures to ensure fast recovery in case of disruption. ICT regulators could have several key functions related to risk assessment and management:

- Defining a risk assessment framework

- Ensuring the implementation of the risk management framework and tracking risk response plans

- Ensuring adequate testing and/or simulations to ensure readiness

- Ensuring 3rd party risk management measures are in place

- Enforcing Incident Management and Vulnerability Disclosure

Defining a risk assessment framework

ICT regulators can create incentives or requirements for operators and service providers to conduct systematic and structured risk assessments by issuing clear and actionable frameworks and guidelines. Developing common criteria and frameworks to assess such risks within the ICT sector at the national level would ensure coordination and consistency among different entities and facilitate the identification of single points of failure to establish redundancy measures ensuring service continuity.

Ensuring the implementation of the risk management framework and tracking risk response plans

ICT regulators can leverage established frameworks and guidelines, such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework or the ISO 27000 series to verify whether operators and service providers are compliant and implement appropriate steps when an attack happens.[64] The assessed risks are to be documented and included in a risk inventory to monitor new risks and facilitate the continuous implementation of mitigation measures.

Ensuring adequate testing and/or simulations to ensure readiness

To ensure that established measures and frameworks are appropriate to face an actual cyberattack, the development and implementation of cybersecurity simulations and exercises could be encouraged by the ICT regulator. In the United Kingdom, the ICT regulator, the Office of Communication (Ofcom), carries out a threat intelligence-led penetration testing scheme known as TBEST with industry stakeholders to identify security providers’ areas of improvement.[65] These exercises simulate real-world attack scenarios and replicate tactics, techniques, and procedures used by malicious actors to test the cyber resilience of organizations as well as the reliability of their frameworks and procedures.

Ensuring 3rd party risk management measures are in place

ICT regulators could also issue guidance and develop frameworks on risk management processes, ensuring appropriate measures are set up and tailored to particular risks. Specifically, ICT regulators should make service providers comply with shared criteria, for example, through licensing schemes, to assess the organization’s risk appetite, including an exception process and controls to be implemented. ICT regulators may also encourage service providers to implement a zero-trust approach. As a result, by enforcing precise, least privilege per-request access decisions in information systems and services in the face of a network viewed as compromised, uncertainty may be reduced.[66]

Due to the variety of stakeholders operating in the ICT sector,[67] it is vital for ICT regulators to guide service providers in considering risks related to the supply chain during risk identification, assessment, and management phases. Moreover, ICT regulators should encourage, or if possible, require network and service providers to develop business continuity plans and management practices to ensure that the entities involved in a cyberattack have the means to provide essential services and not entirely halt their operations. This could be facilitated by relying on cloud services, and ICT regulators might encourage service providers to pursue certification paths that demonstrate compliance toward business continuity standards.

Enforcing Incident Management and Vulnerability Disclosure

The ICT industry’s cybersecurity environment also requires ICT regulators to have a clear overview of the risk environment, and if within their mandate, possibly in collaboration with CIRTs, promote informed policies related to incident reporting and vulnerability disclosure for ICT sector stakeholders. ICT regulators can utilize information that has been reported and made public to inform and adapt their efforts to create new policies and initiatives based on the information they have obtained. Thus, incident reporting could be a practice encouraged by ICT regulators by contributing to issuing guidelines, incident reporting frameworks, and templates to guide service providers in communicating incidents targeting their business. Such reports should include the criteria that require service providers to inform the ICT regulator about the incident, details about the incident, the targeted service, the potential involvement of third-party providers, the impact and duration of the incident, and, when possible, the estimated resolution time.[68] Furthermore, such reports should define timeframes and deadlines for reporting an incident according to its nature and the targeted service, prioritizing those involving CII. ICT regulators could participate in designing mechanisms that facilitate the transmission of information regarding cyber-related incidents, for instance, by creating a communication channel specifically dedicated to incident reporting.

Similar provisions might be applied to vulnerability disclosure, with ICT regulators being best positioned among industry stakeholders to facilitate and encourage. As an example, the U.S. Federal Communication Commission (FCC) provided clear guidance on vulnerability disclosure by issuing a dedicated policy to guide security researchers in conducting vulnerability discovery activities and submitting discovered vulnerabilities.[69] NTIA issued a “Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure Template” to facilitate the design of Vulnerability Disclosure Policies (VDPs).[70] VDPs can be leveraged to provide guidance on the vulnerability information that needs to be shared, as well as encourage those who identify a vulnerability to report it without incurring risks, for instance, via the acceptance of anonymous vulnerability reports as done by CISA.[71] Although NTIA is not the U.S. ICT regulator, it is an interesting example for other regulatory agencies given NTIA’s role as the Executive Branch agency responsible for advising the President on telecommunications and information policy issues.[72] Furthermore, NTIA is entitled to develop policies on issues related to cybersecurity and has established collaboration mechanisms with the FCC, especially regarding spectrum management.[73] The collected vulnerabilities might be included in a database available to service providers to help them increase their cyber resilience. Moreover, ICT regulators should actively promote participation in information-sharing initiatives at both the regional and international levels to facilitate shared cyber threat information and analysis to help mitigate common threats.

Implementing awareness campaigns

Today’s ICT regulators deal with responsibilities related to end-users such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), public and private organizations, and consumers.

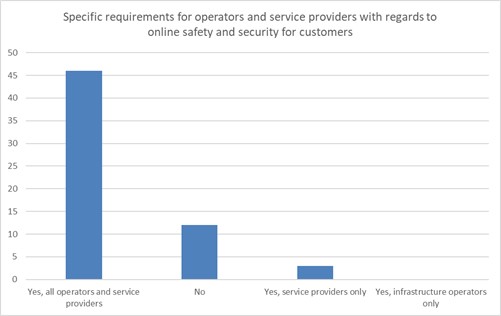

Figure 4: Requirements for operators and service providers with regards to online safety and security for customers (2022)[74]

Given the increasing importance of cybersecurity, ICT regulators – often in collaboration with other relevant agencies and stakeholders – are actively involved in producing and implementing awareness campaigns to share insights and best practices about cybersecurity-related topics to support end-users in developing a better understanding of cyber-related features, as well as in increasing trust toward the digital ecosystem. ITU data shows (See Figure 4)[75] that online safety and security for customers appears to be particularly relevant for regulators worldwide. Indeed, the majority of respondents define specific requirements with regard to ensuring online safety and security for customers for both operators and service providers.

Cybersecurity resilience starts from cybersecurity awareness, and today’s ICT regulators play a leading role in increasing such awareness, developing campaigns targeting SMEs, as well as public and private organizations. An example is represented by the annual European Cybersecurity Month (ECSM) coordinated by ENISA. The campaign “promotes up-to-date cybersecurity recommendations to build trust in online services and support citizens in protecting their personal, financial and professional data online.”[76] Notably, ECSM is currently changing its modus operandi by delivering awareness-raising messages and campaigns all year round to respond to the increasing extent of cyberattacks.[77]

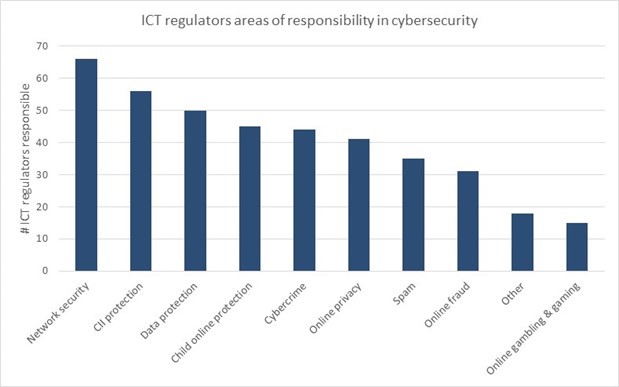

Figure 5: Areas of ICT regulators’ responsibility in cybersecurity (2022)[78]

However, the scope of awareness-raising initiatives and campaigns is wider than increasing the cyber resilience of organizations, governments, and countries. Indeed, their scope includes the safety of the public. Guidelines and best practices focusing on measures to stay safe online can be shared through awareness campaigns and should be intended to ensure that individuals can safely leverage the opportunities of and safely operate in cyberspace. This is key to cybersecurity prevention, especially regarding the risks faced by vulnerable groups like children and elderly people.

This is reflected in Figure 5, where online child protection represents the fourth most common area of responsibility in cybersecurity of global ICT regulators. Children today spend more time online than ever and do so through different devices, such as computers, smartphones, and gaming consoles.[79] Therefore, they are exposed to a wide variety of risks and threats, both from a cyber (e.g., phishing campaigns) and a social perspective (e.g., cyberbullying). In 2020, ITU launched the Child Online Protection (COP) global challenge, requiring a “holistic approach and a global response, international cooperation, and national coordination to protect children from online risks and potential harm and empower them to fully benefit from online opportunities.”[80] In order to fulfil this objective, ITU conducts advocacy and research activities while also issuing guidelines (e.g., the ITU Child Online Protection Guidelines (available in 22 languages)[81]) to support governments strengthening online safety for children. Considering this, ANATEL has launched a “Digital Skills” portal with a dedicated COP page[82]. In this regard, ICT regulators can support the adoption and implementation of such guidelines while also developing awareness-raising initiatives and mobilizing the sector to conduct awareness campaigns.

Improving cybersecurity of ICT products through certification schemes and assurance practices

ICT regulators are increasingly encouraging and developing certifications, labeling, and assurance schemes to facilitate product and service compliance with internationally and nationally recognized security standards, as well as to ensure that cybersecurity products meet expected criteria, including supply chain standards.[83] The adoption of such schemes aims to secure digital assets and products and develop frameworks and guidelines to increase end-user safety and protection in cyberspace. In this regard, the ITU-T Study Group 17 provides insightful recommendations on security standards for ICT products and services.[84]

Furthermore, among national ICT regulators, the development of certification and labeling schemes is embraced by the FCC, which has recently proposed the adoption of a cybersecurity labeling program for smart devices. The proposition consists of a voluntary labeling program that “would provide information to consumers about the relative security of a smart device or product. Smart devices or products bearing the Commission’s proposed IoT cybersecurity label would be recognized as adhering to certain cybersecurity practices for their devices. ”[85]

2.3: Understanding the need for collaborative ICT policymaking and regulation

To ensure the overall objective of a more cyber secure and resilient ICT sector, a strong collaborative approach is required involving all key ICT sector stakeholders from government, industry, civil society, and academia. This consortium should include not only governmental agencies regulating the ICT sector but also stakeholders who functionally rely on ICT infrastructure. For example, when developing ICT-related regulatory initiatives, ICT regulators should institute processes to engage other sectors’ regulators to ensure that interdependencies are accounted for, and responsibilities are appropriately shared. Setting up of collaborative mechanisms ensures that all key stakeholders can share their knowledge and best practices to facilitate the development and implementation of ICT directives and regulations. As discussed in Section 2.2, an example of such engagement processes are the collaboration mechanisms adopted by the Singaporean IMDA to develop standards and guidelines in the domains of cloud and IoT. Alternatively, collaborative mechanisms can be promoted at the regional level. This is demonstrated by the ASEAN Masterplan 2025,[86] a document encouraging collaboration between ICT and competition regulatory authorities across ASEAN to promote principles able to regulate the ICT sector and the wider digital economy.

Considering that ICT infrastructure and its components are mainly used by industry, industrial partners are crucial stakeholder to consult during policymaking. Indeed, digital policies and ICT regulations need to consider the requirements and needs of industry to ensure they are appropriate for both the development and cybersecurity of the ICT industry. Through co-regulation, the industry can collaborate with ICT regulators by developing and enforcing rules, standards, and codes of conduct that address emerging cybersecurity issues while enabling a flexible model that encourages innovation. An example of the successful involvement of industry in consultation for policymaking is the U.S. Transportation Security Administration (TSA)-issued directive imposing cybersecurity requirements on pipeline operators following the 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack. In that instance, the industry managed to make the TSA revisit its new regulation, which was considered too prescriptive. Instead, through negotiation between industry and regulators, they were successful in delivering a revised directive beneficial to both government and industry stakeholders.[87]

Promoting a collaborative policymaking process will ensure that all ICT stakeholders, including industry, ICT consumers, and end-users are accounted for in relevant legislation and regulation. Moreover, it will ensure that regulations and guidelines foster advancements and innovation within the ICT sector, while enhancing resilience against malicious cyber activity in the ICT sector and all other dependent sectors. The European Banking Authority (EBA), for example, has already worked in this direction by developing and publishing specific measures for financial services to account for increased risks derived from ICT interdependencies (e.g., EBA Guidelines on ICT and security risk management).[88]

Additional national ICT regulator efforts should be expended to create regulations that are harmonized internationally. While digital globalization is still booming, nations and regional actors are adopting different approaches to governing international data flows, creating fragmentation and increasing complexity.[89] With the integration of internationally recognized best practices in regulations, ICT regulators can harmonize regulatory approaches and create international consensus on ICT issues, thus facilitating interoperability while ensuring a common standard of security.[90]

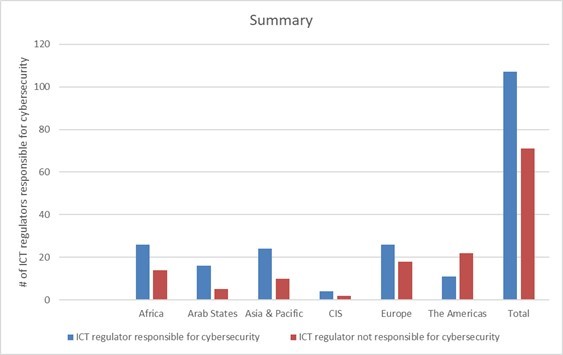

Figure 6: ICT regulators responsible for cybersecurity[91]

Today’s ICT regulators need to balance their traditional approaches and mandates with the current need for a collaborative approach when developing regulations in the cybersecurity field. While ICT regulators have a strong mandate on the provision of traditional services (e.g., spectrum management, interconnection, and universal access management), [92] they also increasingly rely on collaborative governance to expand their cooperation with peer regulators in different sectors to increase consumer benefits and development outcomes in the digital field. As shown in Figures 5 and 6,[93] ICT regulators’ roles and responsibilities in cybersecurity depend on their national mandate, and no one-size-fits-all solution exists.

Nevertheless, collaborative tools enable ICT regulators with a limited mandate on cybersecurity to improve the security and resilience of the digital infrastructures by promoting, for instance, initiatives that ensure cybersecurity governance by operators, foster best practices, diagnose and mitigate threats, promote information sharing, and protect critical infrastructure.[94] The expansion of both the breadth (i.e., by engaging with a new set of national regulators) and depth (i.e., by establishing informal, formal, or hybrid mechanisms of collaboration) of cooperative mechanisms highlights the importance of cooperation among different agencies and regulatory frameworks to shape enabling policies. ICT regulators worldwide frequently collaborate with spectrum agencies, competition and consumer protection authorities, as well as broadcasting and postal authorities, cybersecurity agencies, financial regulators and national coordination bodies.[95] Aside from fostering digital transformation, such collaboration is key to tackling cybersecurity challenges effectively and comprehensively.

However, there is room for improvement in collaborative initiatives between ICT regulators and data protection authorities, CERTs, transport, and energy regulators, as they represent the stakeholders with which ICT regulators cooperate the least.[96] Given their central role in digital societies, ICT regulators must recognize the relevance of collaborative initiatives with these types of stakeholders to strengthen national cyber resilience while fostering connectivity and digitalization.

Examples of national cooperative approaches

United Kingdom

When considering cooperative approaches between ICT regulators and national cybersecurity agencies, the United Kingdom provides an insightful example of how both a national ICT regulator, Ofcom, and a national cybersecurity technical authority, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), can benefit from collaboration. Since the NCSC’s inception in 2016, the agencies have closely collaborated according to formal agreements. In particular, the NCSC provides valuable technical advice on cybersecurity to assist Ofcom in fulfilling its duties, with their collaboration further reinforced by the 2021 Telecommunications Act.[97] A joint statement[98] issued by Ofcom and NCSC highlights the following key aspects:

- NCSC will provide independent expert technical cybersecurity advice to Ofcom to support its monitoring, assessment, and enforcement of the new telecommunications security framework.

- Ofcom and the NCSC will exchange information where necessary and permitted by law. In particular, the two agencies will share information on telecommunications security, and NSCS will share with Ofcom intelligence about specific threats that are likely to affect organizations regulated by Ofcom when appropriate.

- NCSC will provide incident management support during serious cybersecurity incidents to telecommunications operators and Ofcom as necessary. Ofcom will encourage reporting organizations to notify NCSC of the incident and might notify itself the incident if permitted by the law.

Australia

Similar to the case of the United Kingdom, the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) and the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) have reached an agreement to collaborate and exchange intelligence to enforce protection measures for the Australian population.[99] Notably, this cooperative initiative is formalized through a Memorandum of Understanding, underscoring the availability of various levels of formality for establishing cooperation mechanisms between ICT regulators and national cybersecurity agencies.

Saudi Arabia

As mentioned, cooperative initiatives are widespread between the ICT regulator and the postal sector. An insightful example is represented by the Saudi ICT regulator, the Communications, Space and Technology Commission (CST). The ICT regulator established the Cybersecurity Operations Center (ICT-CSIRT) to oversee cybersecurity across the ICT and Postal Sectors, promote collaborative partnerships among service providers, and enhance readiness and response to cybersecurity attacks. In this context, CST (formerly CITC) issued the Regulation for Cybersecurity Operations in ICT & Postal Sector[100] to clearly assign roles and responsibilities to the ICT regulator and service providers in the following domains:

- Cybersecurity information sharing. It enables ICT-CSIRT to effectively fulfill its duties in detecting targeted cybersecurity campaigns, supervising responses to cybersecurity threats and incidents, and enhancing the preparedness of service providers to address such threats and incidents.

- Threat intelligence sharing. It enables the provision of intelligence regarding ongoing cybersecurity threats targeting the postal sector. It also aims to enhance the preparedness of service providers in responding to cybersecurity threats and raise awareness about such threats within the sector.

- Vulnerability monitoring and assessment. It aims to establish regulations governing the exchange of information on vulnerability scanning, disclosure, and evaluation to strengthen service providers’ capabilities in managing, monitoring, and addressing vulnerabilities. Ultimately, the goal is to reduce the sector’s attack surface and enhance its overall security posture.

- Cyber threat hunting. It aims to proactively detect and hunt threats by developing hypotheses that are shared with service providers to look for indicators of compromise that standard monitoring and detection tools may have missed.

- Incidents’ handling. It enables allocating responsibilities to the appropriate entities responding to cyber incidents.

- Incident clarification. It allows the ICT-CSIRT to oversee the response activities of service providers regarding cyber threats and incidents and ensure they are prepared to respond effectively to such threats and incidents.

Based on a solid cooperative approach, the CST regulation aims to advance cybersecurity across the Saudi ICT and postal sectors.

Aside from these examples, Singapore and Brazil represent two other insightful case studies on how ICT regulators can engage with stakeholders external to the ICT sector to increase the national cyber-resilience. Cooperative initiatives led by the Singaporean IMDA with the private sector demonstrate the relevance of a multi-stakeholder approach to address the cybersecurity challenges targeting the ICT sector, highlighting how public-private partnerships can foster cybersecurity solutions. The Brazilian case illustrates how establishing a working group dedicated to cybersecurity can help ICT regulators improve their cybersecurity posture and foster collaboration with other national agencies and stakeholders.

Singapore

In Singapore, formal collaboration mechanisms have been established between the ICT regulator, IMDA, and relevant national bodies on cybersecurity and CERT-related issues to strengthen the country’s national cyber resilience. These include:

- The development of the Cyber Defense Exercise together with the Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) and fourteen other agencies to strengthen Whole-Of-Government (WoG) cyber capabilities to detect and tackle cyber security threats to IT and OT networks controlling the operations of critical infrastructure.[101]

- Collaboration with CSA and Enterprise Singapore (ESG) to include cybersecurity solutions under the SMEs Go Digital Programme. The Programme aims to make it easier for SMEs to adopt advanced digital solutions to go digital and take advantage of the opportunities unlocked by the digital era. In particular, IMDA provides a list of pre-approved cybersecurity solutions assessed to be market-proven, cost-effective, and supported by reliable vendors.[102]

Furthermore, IMDA developed a Cybersecurity Vulnerability Reporting Guide to facilitate and accelerate the reporting of cybersecurity vulnerabilities in telecommunication service providers’ public-facing applications. IMDA also issues guidelines and standards on compliance and certification, such as the Multi-Tier Cloud Security (MTCS) Certification Scheme for cloud service providers in Singapore, representing the world’s first cloud security standard, and guidelines on cloud outage incident response (COIR) to strengthen Business Continuity Management and Disaster Recovery (DR) Plans.[103] Moreover, IMDA provides guidelines and standards on a variety of other digital-related topics, such as IoT, data services, and ET, acting as a leading stakeholder in the digital transformation process.[104] Additionally, the Authority develops programs to increase end-user safety and awareness through tailored programs such as the Data Protection Essentials and the Data Protection Trustmark Certification. The former helps SMEs develop data protection and security practices to protect customer data and quick recovery should a data breach happen.[105] The latter is a voluntary certification that organizations can pursue to increase trust among stakeholders and users.[106]

Brazil

In December 2020, Brazil’s Telecommunication regulator, the Agência Nacional de Telecomunicações (ANATEL), approved a cybersecurity regulation,[107] which came into force in early 2021 and is directed toward telecommunication service providers. Its goal is to promote cybersecurity in telecommunication networks and services in Brazil through a technical and regulatory line of action.

The regulation is integrated into the broader context of cybersecurity efforts advanced by various governmental agencies and spheres, highlighting the importance of a holistic and collaborative approach to cybersecurity. The regulation is aligned with the scope and purpose of the Brazilian National Cybersecurity Strategy and the Brazilian National Information Security Policy. Indeed, the Regulamento de Segurança Cibernética Aplicada ao Setor de Telecomunicações established an asymmetric approach with principles and guidelines that have to be observed by the whole sector and an ex-ante set of controls that telecommunications service providers with significant market power must comply with. This set of mandatory obligations requires all targeted service providers to develop and implement a Cybersecurity Policy that considers national and international standards and best practices, such as providing procedures and controls to identify and rank vulnerabilities in CIs, mapping the identified and assessed risks with the respective response plans, and developing mechanisms ensuring business continuity. The regulation also refers to the need for the targeted Telecommunication service providers to rely on products and services from suppliers that establish strong cybersecurity policies and that undergo into external audit, demonstrating vigilance in controlling the ICT supply chain. Other important provisions include the notification of relevant incidents, the information sharing between the providers and the assessment of vulnerabilities performed by third party. Finally, the regulation envisages sanctions for non-compliant service providers.

The Regulamento also established the Grupo Técnico de Segurança Cibernética e Gestão de Riscos de Infraestruturas Críticas (GT-Ciber, i.e., Technical Group of Cyberscurity and Critical Infrastructure Risk Management). GT-Ciber is responsible for assisting the Agency in monitoring the implementation of the Cybersecurity Policy and identifying CIs, defining the parameters for the implementation of the ex-ante controls, evaluating standards, best practices, and initiatives, promoting awareness and capacity building activities, developing studies, as well as considering the expansion of the scope of the regulation to other stakeholders.[108] Relevantly, GT-Ciber is requested to cooperate with other national agencies and provides inputs to the Brazilian representation in the international telecommunication/ICT organizations, through a close collaboration with the Brazilian Communications Commissions (CBCs).[109]

The Group comprises four technical sub-groups, namely the sub-group on Cybersecurity Policy and Critical Infrastructure Risk Management, the sub-group on Equipment Suppliers and Requirements, the sub-group on International Issues, and the sub-group on Information Sharing and Best Practices. The meetings of these sub-groups include a variety of stakeholders, depending on the issues at stake.

Considering the asymmetric approach, an important mission of the GT-Ciber is to foster initiatives with the aim to promote cybersecurity and cyber resilience of small service providers. In this sense, ANATEL has recently approved basic level cybersecurity guidelines including a checklist to support small telecommunications service providers enhancing cybersecurity and resilience.[110]

2.4: International collaboration

International cooperation is paramount as cyber risks recognize no boundaries. Two working groups addressing cybersecurity matters were established under UN auspices: the Open-ended Working Group on security in the use of information and communications technologies (OEWG)[111] and the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on advancing responsible state behavior in cyberspace in the context of international security.[112] However, only the former is currently active and is mandated by the UN General Assembly to negotiate rules, norms, and principles of responsible behavior of States in cyberspace, establish regular institutional dialogue under the UN, and continue to study existing and potential threats while advancing discussions on cyber capacity-building and confidence-building measures. Differently, the UN GGE was mandated to address norms, rules and principles, confidence-building measures, and how the international law applies to cyberspace. Nevertheless, the UN GGE is currently not active.

ITU launched the Global Cybersecurity Agenda (GCA)[113] in 2007, which consists of a cybersecurity framework for international cooperation to foster confidence and security in the information society. The GCA provides the general foundation and framework for the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI), an index developed by the ITU to measure the commitment of countries to cybersecurity at a global level.[114] Notably, the Agenda and, consequently, the GCI are built upon five working areas, namely legal measures, technical and procedural measures, organizational structures, capacity building and international cooperation. Concerning international collaboration, the GCA recommended that ITU should establish a focal point for coordinating diverse cybersecurity activities and addressing emerging cybersecurity issues. The principles included in the GCA continue to guide international efforts “to ensure safe and trusted use of technology by everyone, everywhere”[115] as re-affirmed by ITU’s Member States during the 2018 Plenipotentiary Conference,[116] ITU’s highest-level meeting. Furthermore, the ITU Council instructed the ITU Secretary-General to submit a report explaining how the ITU is utilizing the GCA framework and, with the involvement of Member States, submit appropriate guidelines for the utilization of the framework. Such guidelines were approved by the Council in 2022.[117] Relevantly, the guidelines on the international cooperation’s pillar focus on the need for the ITU to explore innovative, flexible, and agile mechanisms for building partnerships, as well as engage a wide variety of players and stakeholders while continuing its cooperation with other UN agencies to harmonize and streamline its programs and activities on cybersecurity.[118]

Several countries pursue bilateral agreements targeting cybersecurity and ICT-related cybersecurity as they represent a well-established mechanism to promote cooperation. However, they do not always imply legal obligations. For instance, the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs (DFAT) established several bilateral agreements and partnerships with regional stakeholders to support cyber and critical technology cooperation. In March 2022, the Australian Ambassador for Cyber Affairs and Critical Technology, and the Secretary of Papua New Guinea’s Department of ICT (DICT), signed a renewed Memorandum of Understanding with no legal obligations on cyber cooperation between the two countries aimed at promoting coordination and information sharing, capacity building, and capability and process development.[119]

2.5: Emergency response

Given the critical role of ICT infrastructures in coordinating rescuer response and communicating with those affected by catastrophes or emergencies, the international community established ICT collaboration mechanisms for such circumstances. For example, the Tampere Convention,[120] which was ratified by 49 countries, defines a framework for States, non-governmental entities, and intergovernmental organizations to facilitate the use of telecommunications resources for disaster mitigation and relief, reducing regulatory barriers and recognizing the importance of temporarily abstaining “from the application of national legislation on imports, licensing, and use communication equipment.”[121]

Another example of emergency response activities and ITCs is by the WFP-led Emergency Telecommunications Cluster (ETC), one of the Clusters designated by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) to coordinate efforts during emergencies.[122] ETC highlights the importance of guaranteeing “robust and safe” communication services to support communities in case of emergencies and humanitarian operations and establishing partnerships to provide “reliable, local and safe access to communication during emergencies.” While ICT regulators do not play a direct role in ETC, they can advise relevant authorities to encourage the development of such strategies and promote the inclusion of cybersecurity guidelines in international frameworks, especially in contexts such as those where ETC operates to ensure a safe and secure exchange of information.

Even if both the Tampere Convention and the ETC Strategy 2025 refer to the strategic importance of ensuring the availability of safe and secure communications in emergency contexts, they do not discuss cybersecurity plans or guidelines to safeguard communications from malicious cyber activities. By acknowledging that available and reliable communications, technologies, and services lay at the core of the Tampere Convention and ETC’s mission, the absence of cyber-related guidelines shows how ICT regulators and relevant agencies need to include cybersecurity considerations when developing such frameworks. Humanitarian organizations appear not to be adequately prepared to respond to malicious cyber activities that could impact operations[123] and should therefore consider developing their own cybersecurity strategies.[124] Cybersecurity features might be incorporated within National Emergency Telecommunications Plans (NETP) to align them with the current cyber-related threats that could undermine communication availability during the four phases of disaster management, namely mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery.[125] Consequently, impediments to monitoring the development of emergency situations, analyzing information and data, and implementing strategies might emerge.

2.6: Institutional capacity requirements: the need for cybersecurity professionals

The cybersecurity workforce gap is a worldwide reality, affecting all sectors and environments reliant on cybersecurity services. Defined as the mismatch between the supply and demand of skilled cybersecurity professionals, approximately 4 million needed worldwide in 2023,[126] the gap of skilled cybersecurity professionals can create significant problems for insufficiently staffed organizations. According to the (ISC)2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study 2023, 67% of respondents say their business lacks the cybersecurity personnel necessary to detect and resolve security problems. Additionally, 92% of respondents said their business lacks certain capabilities, with cloud computing security, AI/ML, and Zero Trust implementation being the most prevalent.[127]

This poses an extra challenge to ICT regulators, who need to address the gap within their respective areas of work to assure cyber resilience and decrease the risk of cyberattacks against ICT infrastructure. Despite the cybersecurity workforce having grown by 8.7%, the gap between the number of personnel required and the number available has also widened, rising by 12.6%.[128] This is a concern for ICT regulators and all digital stakeholders because the effective implementation of cybersecurity measures requires personnel with a solid background in cyber-related topics.

A clearer understanding of cyber workforce gaps may allow ICT regulators and stakeholders to coordinate with academic/training institutions and industry organizations to develop tailored educational programs targeting students to prepare the next generation of cybersecurity professionals. The cyber workforce skills’ gap could be reduced also by developing and implementing training and certification paths to strengthen workers’ expertise in cybersecurity. Therefore, ICT regulators could take advantage of their strategic positioning within the digital ecosystem to identify potential areas of improvement for cybersecurity skills and coordinate with other relevant stakeholders (e.g., universities, Ministry of Education) to develop initiatives capable of reducing the cyber workforce gaps.

Case study of existing institutional and human capacity initiatives

Projects to address cybersecurity skill gaps already exist, and, in some cases, they aim to reduce gaps in the ICT sector specifically. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) developed several initiatives to reduce the cybersecurity workforce skill gap and develop a local talent pipeline,[129] including establishing the TeSa FinTech Collective to focus on the ICT domain. Indeed, the initiative’s purpose consists of training industry-ready professionals to meet the demands of emerging ICT skills, including cybersecurity and AI.[130] The initiative is developed together with the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), six local universities, five financial associations, and SkillsFuture Singapore. TeSa FinTech Collective seeks to align ICT skills taught at universities with the industry’s actual needs through courses, mentorship, and hackathons, as well as career guidance and certifications.

Data from the ISC² indicates that there are at least 300,000 vacancies in Brazil’s cybersecurity sector.[131] Thus, the Hackers do Bem program aims to address the need for cybersecurity and privacy professionals with a free of charge training of 30,000 students as well as the growth of the Residency in ICT program, which instructs professionals in ICTs.[132] This program is a multi-stakeholder government initiative led by public and private bodies.

Like other stakeholders in the digital ecosystem, ICT regulators face a cybersecurity workforce shortage. Therefore, ICT regulators might consider focusing on designing solutions to reduce the workforce gap in their sector by relying on training for their personnel and helping develop the future generation of ICT cybersecurity workers.

Section 3: Examining ICT Cybersecurity Regulatory Practices

The following section will examine various components of ICT-related cybersecurity policies and regulations taking into consideration certain national and regional practices.

3.1: National cybersecurity strategies

Publishing a National Cybersecurity Strategy (NCS) can lay the foundation for coordinated national cybersecurity actions. As it is a comprehensive document addressing cybersecurity from different dimensions, with contents and structure that can vary from one country to another according to national priorities, the development of an NCS becomes crucial for aligning and organizing cybersecurity practices within the country. As a central party in the strategy, ICT regulators could consider it to prioritize and encourage cybersecurity actions, if within their mandate, through regulations and policies within their specific sector.

The U.S. National Cyber Strategy from 2023,[133] for example, addresses certain regulatory cybersecurity priorities related to critical infrastructure with a model focusing on “collaborative defense that equitably distributes risks and responsibility” in its Pillar One: “Defend Critical Infrastructure.” The objectives in Pillar One provide recommendations for regulators operating in different sectors by including them to a greater extent in the collaborative approach and providing guidance on establishing cybersecurity measures, including in the ICT sector.

The Strategy provides a plan of action in collaboration with CISA for establishing collective Federal cybersecurity defense for securing Federal agencies’ information systems. Regulators, including the ICT regulator, may be obliged to strengthen their own cybersecurity capabilities. “Modernize Federal Systems,” also under Objective 1.5, mentions how Federal agencies must adopt a zero-trust architecture strategy, including using multi-factor authentication, encrypting data, obtaining insight into their full attack surface, managing permission and access, and using cloud security solutions. The zero-trust approach is based on three principles: verify explicitly, use least-privilege access, and assume breach.[134]

The U.S. example of zero-trust architecture aimed at Federal Agencies,[135] including the FCC, highlights that ICT regulators must also pay close attention to the cybersecurity measures implemented within their institutions.

The Singapore Cybersecurity Strategy 2021,[136] in Strategic Pillar 3: Enhance International Cyber Cooperation, has a goal to foster an open, secure, stable, accessible, peaceful, and interoperable cyberspace. The strategy recognizes that cyber threats are international and cross-border, thus, there is a need to engage and coordinate with international partners to work toward the longer-term goal of a rules-based multilateral order in cyberspace, as well as to build procedures and policies to enhance the global baseline level of cybersecurity.

Considering that Singapore’s strategy concentrates efforts to Enhance International Cyber Cooperation, there is a clear demonstration that ICT regulators could prioritize actions to establish rules, norms, principles, and standards strengthening not only national but also global cybersecurity readiness, helping to tackle cross-border cyber threats and cybercrime on a global scale.

In summary, the good practices related to National Cybersecurity Strategies demonstrated by these examples are the following:

- National Cybersecurity Strategies provide overarching guidance to be considered by ICT regulators, including the establishment of national regulatory priorities and the importance of international collaboration to address transnational cyber threats and governance issues.

- National Cybersecurity Strategies can lay the grounds for securing the regulators’ own information systems, through modernizing IT and OT systems so that they are able to use critical security technology (e.g., technology suitable for implementing a zero-trust approach).

3.2: Identifying and protecting CNIs and CIIs

This section provides examples of national and regional regulation adopted to define criteria for the identification of CNIs or CIIs and the setting of rules for their protection.

The European Union’s Network & Information Security Directive, known as the NIS Directive[137] was adopted in 2016 and replaced by a new Directive in 2023, namely NIS2. The NIS Directive established obligations for operators of essential services (OES),[138] which can operate in sectors such as energy, transport, banking, drinking water supply and distribution, healthcare, Digital Infrastructure, and for digital service providers (DPS). It also harmonized national Member State cybersecurity capabilities, cross-border collaboration, and critical sector monitoring across the EU.[139] One of the sectors included in the scope of the NIS Directive was Digital Infrastructure with Internet Exchange Points (IXPs), Domain Name System (DNS) service providers, and Top-level Domain (TLD) name registries as types of services that could be considered as essential.

While the 2016 NIS Directive did not apply to telecommunications providers as they were subject to specific regulatory requirements under the European Electronic Communication Code (EECC),[140] NIS2 broadened the original NIS scope to include new sectors and entities, set new standards, and clarify ambiguities.[141] NIS2 aims to integrate all critical infrastructures under a single security framework and also applies to telecommunication providers, including the EECC public electronic communication networks (“ECN”) and services (“ECS”) in its scope.

In the United Kingdom, Ofcom released guidance[142] for the digital infrastructure subsector outlining how functions under the NIS Regulations should be approached. The guidance is primarily relevant to operators of essential services (OES) governed under Digital Infrastructure. It covers the crucial aspect of identification and designation of OES. The guidance also provides details on how persons considered to be OES must inform Ofcom of security incidents, how Ofcom can investigate compliance, as well as enforce the NIS Regulation requirements.

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the “UAE Information Assurance Regulation”[143] was issued by the ICT Regulator, the Telecommunications and Digital Government Regulatory Authority (TDRA), in 2020 to establish a trustworthy digital ecosystem by setting minimum standards for the protection of information assets and supporting systems across all entities in the country. The regulation seeks to provide a response to the expanding cyber threats against national security and CII assets, which are increasingly being targeted by cyber threat actors, including criminal groups and hacktivists. Considering that an attack or a large-scale outage on the assets supporting CII can have cascading effects and potentially impact a significant portion of the population or important societal processes,[144] it is important that ICT regulators engage in identifying and protecting not only CII but also their relevant assets, services, resulting interdependencies, and third parties that may be connected.