Competition and regulatory challenges for microstates

25.08.2020Introduction

Throughout the world consumers have similar expectations from the digital economy. They look for data speeds, network coverage, and reliability that allows effective access to the myriad of cloud-based and over-the-top (OTT) services that are now available, and they expect prices both for services and for equipment to be set so that they can afford to access such content. In order to meet these expectations, most countries have adopted a model of regulated competition, in which a small number of licensed network operators compete to provide digital networks and services, each of which is supervised by a national regulatory authority.

ICT regulators in microstates (i.e. small and emerging nations)[1] face specific challenges. Lack of scale, often accompanied by remoteness and/or limited economic development, make it hard to attract investment capital and harder still to ensure the availability of affordable services. With limited scope for competition, the role of regulation is even more critical than in other countries, but regulators generally have fewer resources available to them. In contrast, the service providers are typically international companies which are able and willing to spend money with the aim of achieving regulatory capture.

Economies of scale

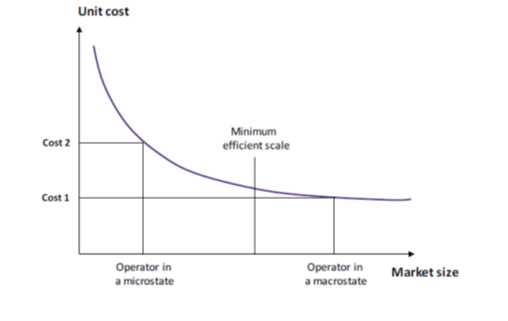

The key challenge is that of economies of scale. There are substantial fixed costs for a telecommunications network, irrespective of the number of customers who will use that network. As the number of customers shrink, the cost per customer grows because the fixed costs must be recovered from fewer customers.

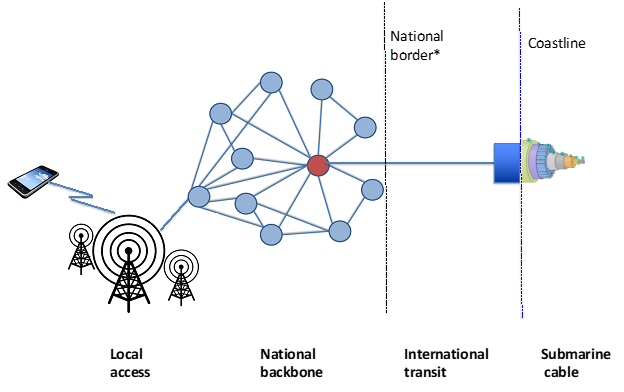

The diagram above shows the main cost components of Internet access:

- Local access: this can be provided through a fixed or Wi-Fi connection to the national network, but in the majority of cases in developing countries it will be provided over a mobile network.

- National backhaul: the link from the mobile access network to the international gateway or (for landlocked countries) to the national border.

- International transit: for landlocked countries (and occasionally for others) there is a need to purchase capacity on another country’s network to reach the cable landing station.

- Submarine cable: investment in, or lease of, capacity from whichever of the submarine cables that lands in the country.

The key point about almost all of these costs, and especially the last three categories, is that they are predominantly fixed costs: there is a sizeable up-front investment and a relatively small cost for incremental capacity. As a result, there are substantial economies of scale to be had which means that small developing countries will inevitably suffer from higher unit costs and higher end-user prices.

The extent to which scale economies are reduced and unit costs increased depends on the demographic and geographic characteristics of the country.[2] Countries with a small population will suffer significantly higher costs as they have the least opportunity to realize economies of scale, and countries where the population is spread over a large land area (i.e. a low population density) will suffer from increased fixed costs of network coverage and higher unit costs. Furthermore, landlocked countries incur additional costs because of the need to lease international transit capacity and island nations suffer higher costs because they need to deploy submarine cables for domestic as well as international services.[3]

In microstates, telecommunication services will often be operating well below minimum efficient scale because of market size. This means that regulators will have to make a trade-off between encouraging higher levels of competition against requirements for lower production and end-user costs. More operators mean a lower number of customers per operator and an increased challenge for operating on a scale that is economically viable.

Source: Plum Consulting 2017.

The procurement power of smaller markets is also lower, further exacerbating the impact of costs. Procurement discounts that are commonplace in larger nations are seldom available to microstates; indeed, it can be difficult to attract the interest of suppliers in even quoting for contracts. Operators or governments in microstates are of a lower priority to large vendors and they will often have to wait longer for supply.

Regulation without (much) competition

Many microstates have a single national network, certainly for fixed network services and often also for mobile services. The rationale is that a single operator is in a better position to dimension and plan the construction of the network (technical efficiency) and to avoid duplication of investments and excess capacity (operational efficiency). Efforts to introduce competition in microstates have often resulted in controlled liberalization with usually just one fixed network operator and a duopoly structure for mobile services. This then requires a greater reliance on ex-ante regulatory tools such as market reviews, interconnection rules, and retail price controls, and this brings additional costs of regulation.

| Example microstates | Number of fixed network licensees | Number of mobile network licensees |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1 | 2 |

| Belize | 1 | 2 |

| Burundi | 1 | 3 |

| Comoros | 1 | 2 |

| Curaçao | 1 | 2 |

| Eswatinia | 1 | 1 |

| Falkland Islandsa | 1 | 1 |

| Liberia | 1 | 3 |

| Micronesiaa | 1 | 1 |

| Palaua | 1 | 1 |

| Samoa | 1 | 2 |

| Solomon Islandsa | 1 | 1 |

| Vanuatu | 1 | 2 |

Note: a. In these countries a single company provides all fixed and mobile services.

The telecommunications industry values transparent and stable regulations; the lack of these can work as a disincentive to investment. A modern, robust, and fit-for-purpose legal and regulatory framework for telecommunications is fundamental for its growth and development. However, a challenge faced by many microstates is out-of-date legal frameworks and the dedicated expertise required appropriately to update legislation.

A further challenge faced by microstates is knowing where to turn for appropriate regulatory models. The majority of research and available telecommunication benchmarks are from larger countries and often do not translate well into the context of microstates. Microstates need to keep regulation to the minimum necessary as regulation itself comes at a higher cost to microstates. Costs can easily spiral out of control particularly if regulatory models are transferred from a larger jurisdiction without appropriate scaling.

As a result, regulatory change in microstates needs to be approached with caution, an understanding that effective change is not to “copy and paste” from macrostates. Whereas all macrostates are to a significant extent similar, each microstate is different and faces its own unique challenges. Digital regulation in every microstate therefore needs to be approached with creativity and pragmatism.

Endnotes

- There is no single definition of a microstate, but it will typically have a very small population or/and a very small land area. For the purposes of this article, the key factors are population (typically less than 500 000) and the level of economic development (GDP less than USD 5 000 million). However, other factors such as population density, remoteness and geographical terrain may also be significant. ↑

- A study in 2018 found that even within developing nations, there could be a tenfold variation on costs because of geographical factors (see A4AI 2018: 24). ↑

- This assumes that a submarine cable is available; microstates are often too small to justify a spur off the closest submarine cables (unless they obtain international aid). ↑

References

A4AI (Alliance for the Affordable Internet). 2018. 2018 Affordability Report. Washington, DC: A4AI https://a4ai.org/affordability-report/.

Plum Consulting. 2017. Effective Telecoms Regulation in the Island States of the Caribbean. London: Plum Consulting. https://plumconsulting.co.uk/effective-telecoms-regulation-island-states-caribbean/.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022