Article: Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

28.08.2020Introduction

It was Benjamin Franklin who famously opined that “nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” And, as he might have gone on to say, human beings try desperately to avoid both of these certainties. Tax avoidance (legal) and tax evasion (illegal) are as old as the concept of taxation itself. But in the digital world, especially for global digital service providers, avoiding taxes has become a lot easier. Regulators and tax authorities are now trying to catch up.

Why is BEPS a problem?

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines base erosion and profit sharing (BEPS) as “… the tax planning strategies used by multinational companies to exploit gaps and differences between tax rules of different jurisdictions internationally to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax jurisdictions where there is little or no economic activity.”

BEPS has a number of significant and detrimental consequences (OECD 2013):

- It reduces the corporate tax revenue that is available to governments.

- It undermines the fairness and integrity of international tax rules, leading to greater incentives for entities to avoid tax.

- It fundamentally distorts competition between domestic and multinational entities.

- It enables multinationals to leverage their contrived tax savings into price cutting (potentially predatory pricing), to invest in greater capacity (scale) and to invest in new services (scope).

Concerns about BEPS have been rising as globalization has increased, but the emergence of the digital economy has added substantially to those concerns. The OECD report (OECD 2013) identified three characteristics of value creation in the digital economy that contribute to a dramatic rise in BEPS: scale without mass, a heavy reliance on intangible assets, and the role of data and user participation. These characteristics mean that digital platforms offering global services are readily and legally able to shift revenues between jurisdictions by offshoring intangible assets and using transfer-pricing techniques, so that they minimize their overall tax burden. This may, and often does, create a massive misalignment between the revenues booked and taxes paid on the one hand, and the real economic activity in the country on the other hand. Within the European Union, it has been estimated that digital businesses face an effective tax rate of only 9.5 per cent compared with 23.2 per cent for traditional businesses (European Parliament 2018).

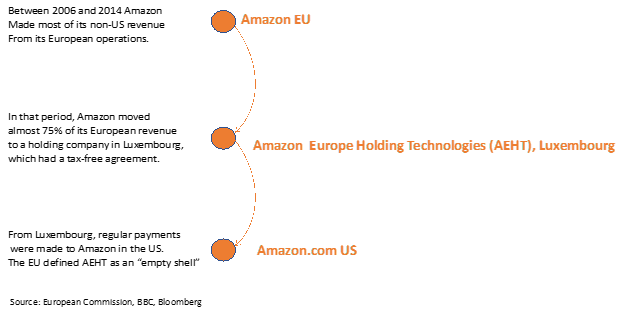

BEPS affects different countries in different ways. For a few countries, those with low taxation regimes designed to attract international companies, BEPS is favourable. But for the vast majority of countries, BEPS deprives them of tax revenues that they could reasonably expect to receive from the digital platform providers. For larger, developed countries this is a political issue about fairness: why should a wealthy company such as Amazon pay just 0.02 per cent tax in the United Kingdom while most companies are paying 20 per cent? (Armstrong 2019). In developing countries, the absolute level of tax revenues forgone are of much greater significance, as they make a real difference to the funds available for investment, including investment in the communications infrastructure upon which the digital platforms depend.

What is being done to counter BEPS?

Efforts to counter BEPS have been both multilateral and unilateral. The multilateral initiatives have been led by the OECD, which was commissioned in 2012 by the G20 finance ministers to investigate BEPS and develop an action plan. Its report (OECD 2013) including the BEPS Action Plan was eventually agreed by the G20 in 2015, providing a convention to develop tax treaty measures to prevent BEPS. However, changes to international tax systems are inevitably slow and, while progress has been made, no consensus-based solution has yet emerged.

Alongside efforts to reform the international tax system, the OECD has also investigated the specific issues related to digitalization, again commissioned by the G20 finance ministers. In an interim report (OECD 2018), Member States were grouped into three categories:

- Those who viewed the reliance on data and user participation as leading to misalignments between where profits are taxed and where value is created.

- Those who view globalization and the ongoing digital transformation of the economy as a fundamental challenge to the international tax framework.

- Those who believe the BEPS package has largely addressed concerns about double non-taxation, although it is still too early to fully assess the impact of all the BEPS measures.

Acknowledging these divergences, the OECD committed to undertake a full review of two fundamental concepts relating to how taxing rights are allocated between jurisdictions:

- “Nexus” – how to establish a link between economic activity and national jurisdiction given that physical presence is not essential to conduct business in the digital economy.

- “Profit allocation” – how to attribute revenues based on where value is created (and hence may be taxed) given the prolific cross-border use of digital information.

The OECD is working towards a consensus-based solution by the end of 2020. The “unified approach” which it is pursuing involves the division of profits into three separate amounts (A, B, and C) which will be allocated between jurisdictions in different ways. Amount A is the major item and represents the share of profits according to the economic activity in each jurisdiction. Amount B is a fixed remuneration to cover distribution and marketing activities. Amount C represents additional in-country activities over and above those captured by the baseline of Amount B.

Meantime, impatient for an international solution to emerge, a number of countries have started to apply their own solutions unilaterally. There have been two basic approaches:

- Applying a corporate tax that is paid by the digital platform. For example, a new digital services tax was introduced in the United Kingdom in April 2020, set at 2 per cent of U.K. revenues, and applying to search engines, social media platforms, and online marketplaces that derive revenues of more than GBP 25 million (about USD 33 million) from British users, and have global revenues of more than GBP 500 million (about USD 660 million) (HMRC 2020). This follows similar schemes in France,[1] Italy, and Australia. A broader scheme has also been developed by the European Union (European Commission 2018) (see box below) which was approved with minor amendments by the European Parliament in December 2018 (European Parliament 2018).

- Applying a tax that is paid by end users. This approach has been adopted in a number of developing countries, where the governments do not have sufficient leverage to tax the digital platforms directly. For example: Uganda introduced a social media tax in July 2018 that requires all users to pay UGX 200 (about USD 0.05) per day for use of OTT services; in Tanzania online content providers have to pay an annual licence fee TZS 1 million (about USD 930) for producing online content (and their content is subject to vetting) (Pollicy 2019). Similar schemes have also been introduced in Kenya and Zambia, although in Benin a proposed tax of CFA5 (about USD 0.008) per MB was repealed after public outcry. However, these schemes tend to be self-defeating because taxing users tends to reduce the affordability of Internet access and suppress demand, which results in lower GDP and lower tax revenues overall.

In June 2021 the leaders of the G7 group of leading economies proposed the alternative of a 15% minimum global corporation tax to be levied where revenue is made, a proposal which received the green light from the G20 in July 2021.

Digital services taxation in the European UnionOn March 21, 2018, the European Commission proposed new rules to ensure that digital business activities are taxed in a fair, growth friendly way in the EU, and makes two legislative proposals: 1. Common reform of the EU’s corporate tax rules for digital activities Even if a company does not have a physical presence in the EU, Member States can tax profits generated in their territory. With these new rules, online businesses contribute to public finances at the same level as traditional companies. A digital platform will be deemed to have a taxable “digital presence” or a virtual permanent establishment in a Member State if it fulfils one of the following:

The new rules will also change how profits are allocated to Member States in a way that better reflects how companies can create value online, for example, depending on where the user is based at the time of consumption. 2. Proposal 2: An interim tax on certain revenue from digital activities This interim tax ensures that those activities which are not effectively taxed would begin to generate immediate revenues for EU Member States. The tax applies to revenues created from activities where users play a major role in value creation and which are the hardest to capture with current tax rules, such as revenues created from:

Tax revenues would be collected by the Member States where the users are located and will only apply to companies with total annual worldwide revenues of EUR 750 million and EU revenues of EUR 50 million. This limit will help ensure that smaller start-ups and scale-up businesses remain unburdened. Source: Derived from ITU 2018: 110-111. |

The way forward

Ultimately the solution to digital taxation will come from reform of international tax treaties. The OECD continues to lead the negotiations and a statement in early 2020 suggested that a unified approach could still be agreed this year (OECD 2020). However, even among OECD members there are residual differences of opinion on major issues, and a resolution of those issues during 2020 is not guaranteed, particularly given the difficulties created by the Covid-19 pandemic.

A notable feature of the OECD proposals is that Member States would have to repeal their various unilateral schemes for addressing BEPS as a consequence of signing up to the multilateral agreement. This gives hope for a single global solution to emerge, but the more those unilateral solutions are embedded the greater the risk that nations will prefer to stick with their own schemes rather than ratify and participate in the international agreement. The stakes are high, and time is short.

Endnotes

- The French scheme illustrates the political difficulties of digital services taxes, which disproportionately fall on U.S. companies (specifically Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft). A 3 per cent tax was proposed in 2019 but was postponed in January 2020 when the U.S. government threatened to retaliate with import taxes on French produce such as wine and cheese. ↑

References

Armstrong, Ashley. 2019. “Amazon pays just £220m tax on British revenue of £10.9bn.” The Times, September 4, 2019. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/amazon-pays-just-220m-tax-on-british-earnings-of-10-9bn-vv9fwxx52.

European Commission. 2018. Fair Taxation of the Digital Economy. https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/company-tax/fair-taxation-digital-economy_en.

European Parliament. 2018. Report on the Proposal for a Council Directive on the Common System of a Digital Services Tax on Revenues Resulting from the Provision of Certain Digital Services. , https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2018-0428_EN.html.

OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development). 2013. Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/ctp/BEPSActionPlan.pdf.

OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development). 2018. Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/ctp/tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-interim-report-9789264293083-en.htm.

OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development). 2020. Statement by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS on the Two-Pillar Approach to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-by-the-oecd-g20-inclusive-framework-on-beps-january-2020.pdf.Pollicy, 2019. Offline and Out of Pocket: The Impact of Social Media Tax in Uganda. Pollicy.org http://pollicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Offline-and-Out-of-Pocket.pdf.

TCRA (Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority). 2018. The Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations, 2018. https://www.tcra.go.tz/en_documents/59.

HMRC (HM Revenue and Customs). 2020. Digital Services Tax. Policy paper. London: HMRC. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-digital-services-tax/digital-services-tax.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022