Access pricing for very high capacity networks in the European Union

28.08.2020Introduction

The European Commission (EC) has given a lot of attention to the matter of how access prices should be set so as to encourage investment in very high capacity networks whilst maintaining effective competition at the retail level. The guidelines developed in Europe provide a useful benchmark for regulators elsewhere, in particular for regulating the price of access to fibre of cable networks.

The European Electronic Communications Code

The Directive establishing the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC) was adopted by the European Parliament on December 11, 2018 (European Union 2018). The purpose of the EECC is to respond to the increasing convergence of telecommunications, media and information technology so that (European Union 2018: Recital 7):

- all electronic communications networks and services should be covered to the extent possible by a single European electronic communications code established by means of a single Directive.

The focus of the EECC is the development of very high capacity networks (VHCNs) regardless of the delivery technology (European Union 2018: Article 61(1)):

- National regulatory authorities … shall … encourage and, where appropriate, ensure … adequate access and interconnection, and the interoperability of services, exercising their responsibility in a way that promotes efficiency, sustainable competition, the deployment of very high capacity networks, efficient investment and innovation, and gives the maximum benefit to end-users.

The EC’s preference is for the market-driven deployment of VHCNs so as to provide competitive outcomes for end users. Only in the event of high and non-transitory economic or physical barriers to replication should regulatory outcomes be imposed. And those outcomes should be imposed only on passive infrastructure unless or until such obligations have been demonstrated to be insufficient.

What are high and non-transitory barriers to replication?

The question of high and non-transitory barriers to replication presupposes a business perspective regarding an investment decision to replicate an asset, which may be hampered if there are technical, legal, or economic barriers to replication. The term “high and non-transitory” barriers to replication alludes to the three-criteria test used in the market analysis for determining whether a market should be subject to ex-ante regulation.

In industries characterized by the presence of infrastructure, high investment is needed, even before market entry, to duplicate the network assets of incumbent suppliers. Typically, the firm needs to realize a certain scale in order to recoup these investments; that is, these investments give rise to economies of scale as utilization of network assets increases. The extent to which scale economies render replication socially inefficient depends on whether, after entering the market by duplicating the assets, there is scope for product differentiation and innovation increases. If there is such scope, post-entry competition is more likely to be based on non-price characteristics of the product or service, which enables prices to include mark-ups necessary for recovering of investment. In the absence of differentiation and innovation, services are homogeneous so that competition will be fierce and focused on price, thus driving down profits and inhibiting investment.

Replication barriers may be considered “non-transitory” when the need for making these investments is unlikely to disappear in the future (e.g. owing to limited scope for technological developments) or when it is unlikely that, given the degree of post-entry price competition, the firm will be able to realize sufficient scale. Concerning the latter, the regulatory framework recognizes that potential entrants face a “chicken and egg” problem: they need critical mass before they are able to invest, but without investing they are unable to generate critical mass. To address this problem, the ladder of investment concept is intended as a two-stage approach, where regulated access to the incumbent’s infrastructure first helps challengers to obtain sufficient scale, and once that has happened, the access obligation can be lifted in accordance with a predefined sunset clause. But the overall objective is always to secure infrastructure investment so as to enhance innovation and increase consumer welfare.

Barriers to replication are therefore high if an entrant, after investing in its own infrastructure and capturing a substantial part of the market, is still not able to earn a profit. These high barriers to replication are non-transitory if temporary access obligations are not able to catalyse challengers’ investments in their own infrastructure.

Why is the focus on passive infrastructure?

The EECC is clear and consistent in its preference for restricting access regulation to passive infrastructure. The reason is spelt out in Recital 187 (with emphasis added):

- Where civil engineering assets exist and are reusable, the positive effect of achieving effective access to them on the roll-out of competing infrastructure is very high, and it is therefore necessary to ensure that access to such assets can be used as a self-standing remedy for the improvement of competitive and deployment dynamics in any downstream market, to be considered before assessing the need to impose any other potential remedies, and not just as an ancillary remedy to other wholesale products or services or as a remedy limited to undertakings availing themselves of such other wholesale products or services. National regulatory authorities should value reusable legacy civil engineering assets on the basis of the regulatory accounting value net of the accumulated depreciation at the time of calculation, indexed by an appropriate price index, such as the retail price index, and excluding those assets which are fully depreciated, over a period of not less than 40 years, but still in use.

The emphasis is on reusable assets, such as ducts, poles, and manholes. Access to these assets can materially improve the prospects of competitive outcomes for end users and overcome physical and economic barriers that might otherwise be insurmountable for new market entrants. These potential and consequential benefits justify the imposition of a discounted regulatory value when setting prices for access to such assets.

It is important in this context to note that trenches are not physical assets in the manner of ducts, poles, or manholes. Trenching is the capitalized installation cost for another asset, either ducts (in the event that they are deployed) or cables (in the event that they are directly buried). Trenches are therefore “reusable” only to the extent that the installed physical asset, to which trenching costs are allocated, are themselves reusable (i.e. only where there are ducts).

In the pursuit of VHCNs it is clear that, whereas ducts are in general fully reusable, this is not the case for copper or coaxial cables: they will, at least beyond the first concentration/distribution point in the network, sooner or later need to be replaced by fibre. Indeed, the EECC also allows for the possibility that in due course fibre itself may be replaced by other technologies, in particular wireless technologies (European Union 2018: Recital 13):

- The current response towards that demand is to bring optical fibre closer and closer to the user, and future very high capacity networks require performance parameters which are equivalent to those that a network based on optical fibre elements at least up to the distribution point at the serving location can deliver. … In accordance with the principle of technology neutrality, other technologies and transmission media should not be excluded, where they compare with that baseline scenario in terms of their capabilities. The roll-out of such very high capacity networks is likely to further increase the capabilities of networks and pave the way for the roll-out of future wireless network generations based on enhanced air interfaces and a more densified network architecture.

Approach to access pricing

The EECC reaffirms the approach to setting access prices that it previously set out in 2013 (European Commission 2013) to promote competition and to enhance the broadband investment environment. It includes recommendations on costing methodologies used for determining the level of regulated access prices.

The Commission considers that (European Commission 2013: Recital 29):

- The bottom-up long-run incremental costs plus (BU LRIC+) costing methodology best meets these objectives for setting prices of the regulated wholesale access services. This methodology models the incremental capital (including sunk) and operating costs borne by a hypothetically efficient operator in providing all access services and adds a mark-up for strict recovery of common costs. Therefore, the BU LRIC+ methodology allows for recovery of the total efficiently incurred costs.

The Commission reasons that, since a BU LRIC+ methodology calculates current costs on a forward-looking basis (and therefore recovers the costs that an efficient network operator would incur if it would build a modern network today), it provides the correct and efficient signals for entry. Since operators with significant market power (SMP) would react to competition by upgrading their copper networks, and progressively replace them with fibre, the methodology should calculate the current costs of deploying a modern efficient VHCN.

The Commission is, inter alia, particularly focused on the valuation of assets. Current costs best reflect the replicability of assets. However, the Commission recognizes that civil engineering assets (ducts, trenches, poles) are unlikely to be replicated, but instead could be redeployed within a VHCN. The Commission therefore recommends using a regulatory asset base (RAB) corresponding to the reusable legacy civil engineering assets based on the following principles:

- be valued at current costs;

- take account of the assets’ elapsed economic life (cost already recovered);

- use an indexation method, relying on historical data on expenditure, accumulated depreciation and asset disposal (as available from the SMP operator’s statutory and regulatory accounts) and on a publicly available price index (i.e. retail price index);

- be locked-in and rolled forward.

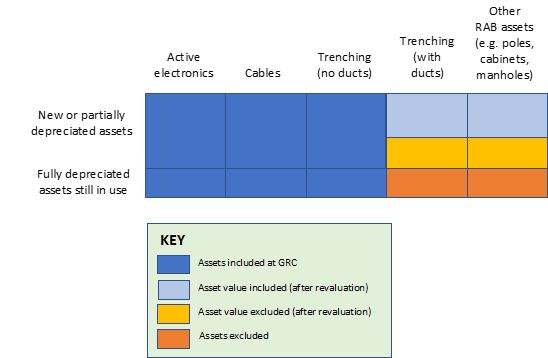

It is apparent from this delineation that the transmission medium should not be revalued in the same way as passive infrastructure. Within the RAB, adjusted valuations should only apply to non-replicable civil engineering assets such as ducts, poles, and (in some cases) trenches, and only to the extent that they can be reused within the VHCN. RAB assets that are fully depreciated are excluded entirely because their cost has already been fully recovered, while partially depreciated assets are revalued and included to the extent that the remaining asset lifetime. RAB modelling thereby avoids the risk of cost over-recovery for reusable legacy civil infrastructure, which would send inefficient market entry signals for build-or-buy decisions.

The figure above shows how the EC costing methodology means that some of the gross replacement cost (GRC) of assets is excluded from access prices. Typically, 10-20 per cent will be excluded depending on the extent to which the network deploys ducts.

References

European Commission. 2013. Commission Recommendation on Consistent Non-Discrimination and Costing Methodologies to Promote Competition and Enhance the Broadband Investment Environment. C(2013) 5761. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/commission-recommendation-consistent-non-discrimination-obligations-and-costing-methodologies.

European Union. 2018. Directive Establishing the European Electronic Communications Code. European Union 2018/1972. Official Journal of the European Union (17.12.2018). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L1972.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022