The decline and fall of mobile termination rates in Europe

26.08.2020Mobile termination rates in Europe

Source: BEREC 2019.

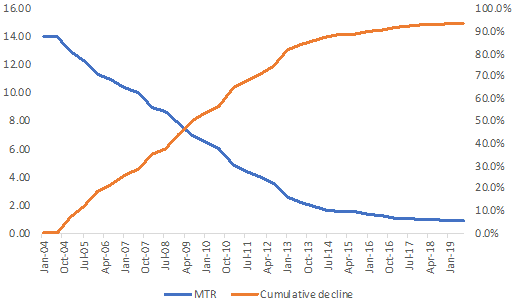

The figure above shows the evolution of (simple) average mobile termination rates in Europe. The average rates in Europe steadily decline from EUR 0.14 (January 2004) to EUR 0.0088 (January 2019), a cumulative decline of 93 per cent from the initial average rate. This article explores why such a dramatic fall in prices has occurred.[1]

How mobile termination rates have been regulated

Historically the common position among national regulatory authorities (NRAs) around the world is that the termination of voice calls to mobile customers is a separate market in which each mobile operator has a monopoly over termination of calls to its own customers. Mobile termination rates (MTRs) – the interconnection cost to terminate a voice call on a mobile network – have been the subject of much scrutiny by NRAs worldwide. In those countries with calling party pays (CPP)[2] arrangement, regulators have frequently found that mobile operators have been charging significantly more than cost to terminate calls on their networks. Therefore, in most cases NRAs have intervened in the mobile termination market to lower the MTRs.

Why were mobile termination rates excessive?

There were several reasons for mobile operators setting MTRs significantly higher than cost.[3] First, when CPP is the arrangement in place, there is a weak relationship between the demand for the service and the MTR. Since mobile subscribers do not have to pay for incoming calls, the MTR has relatively little impact on their choice of network operator. As liberalization proceeded, NRAs allowed other network operators to enter the mobile market, but in most cases a number of years later than the incumbent. This gave substantial first mover advantages to incumbents which, meanwhile, were able to draw large numbers of subscribers to their network. New entrants setting interconnection agreements were faced with traffic asymmetries that made them have a higher cost (more calls would flow from the entrant to the incumbent which had a lot more subscribers). The incumbent would have a cost advantage, as it would pay a lot less to the entrant because of the imbalance of interconnecting traffic, and this advantage was exacerbated by high MTRs.

Higher MTRs also permitted larger mobile operators to price discriminate between on-net and off-net calls. The existence of high off-net prices when compared to on-net prices for the subscribers of the same network, reintroduces the network externality.[4] If price discrimination between on-net/off-net calls is significant, “new” customers will rather join the network that has a higher number of subscribers and may prefer to remain there (another less convenient option is to have two SIM cards). This price-driven effect is referred to as a “tariff-mediated network externality” and is widely documented in the economic literature as forming a strategic barrier to market entry and expansion. For this reason, NRAs intervened to lower termination rates by imposing a price cap, allowed asymmetry between rates for two to three years after a new network operator entered the market, and sometimes imposed a limit on price discrimination between on-net and off-net mobile voice calls.

Opposing views from the beginning

As soon as NRAs started to impose price caps on mobile termination services there were opposing views, intense debate and, in some places, litigation in the courts. For NRAs, in general, the principal reason for reducing MTRs was to benefit end users. Such was the case in the United Kingdom in 2003. The regulator (Oftel at the time) estimated that consumers would benefit by GBP 190 million per year through lower call termination rates (fixed to mobile) arising from a 15 percent reduction (Oftel 2003). The UK Competition Commission, which had spent a full year on a detailed inquiry of the mobile market, concluded that in the absence of termination rate regulation:

- the termination rates of the four mobile operators operated against the public interest;

- termination rates at the time were 30-40 per cent above a fair charge;

- consumers were paying too much for calls from fixed lines to mobiles and from one mobile network to another;

- the high cost of termination constrained calls from fixed-to-mobile numbers; and,

- those making calls to mobiles, were unfairly subsidizing mobile customers who mainly received calls or mostly made on-net calls.

However, there were opponents of MTR reductions (usually the larger mobile operators in each country) which claimed that there were two potential problems with lowering MTRs:

- Lowering MTRs may not be passed on to users through lower retail tariffs for mobile-to-mobile off-net calls.

- Lowering MTRs could make mobile network operators raise call retail prices for mobile users (the so-called “waterbed effect”).

The European Commission Recommendation of May 7, 2009 (European Commission 2009a) on the Regulatory Treatment of Fixed and Mobile Termination Rates in the EU was particularly relevant to the decline of mobile termination rates in Europe. The Recommendation suggested that NRAs should set price cap mobile termination rates based on efficient costs, and should be symmetrical, within a timeline clearly defined (by 31 December 2012). The interpretation of “efficient costs” in the specific context of termination charges meant that a different cost standard – pure long run incremental cost (LRIC) – was employed to calculate cost-based termination rates.

The pure LRIC approach

The pure LRIC of a wholesale call termination service includes only those costs that would not be incurred if the termination service were no longer produced (i.e. the avoidable costs[5]). As the EU Commission Recommendation says (European Commission 2009a: 69):

“The further termination rates move away from incremental cost, the greater the competitive distortions between fixed and mobile markets and/or between operators with asymmetric market shares and traffic flows. Therefore, it is justified to apply a pure LRIC approach whereby the relevant increment is the wholesale call termination service and which includes only avoidable costs.”

The Explanatory Note (European Commission 2009b: 17), published alongside the Recommendation, provided additional justification for a pure LRIC approach, by giving further detailed explanations about the economic reasoning behind the decision:

“A pure LRIC approach, while recognising the essential objective of short-run marginal cost pricing, also recognises that cost structures in network industries tend to be characterised by substantial fixed costs and (by assuming that all costs become variable over the long run) provides for the recovery of service-specific fixed costs and variable costs which are incremental to providing the service over the longer term.”

As the pure LRIC cost standard provides for a lower termination value than standard LRIC approach,[6] the change accentuated the decline of termination rates around Europe. The European Commission justified the change in cost methodology on the basis of harmonization across the EU and on the grounds of consumer welfare. It faced a lot of inconsistencies and contradictions in the remedies used and substantial differences in termination rates among countries, particularly the maintenance of asymmetric termination prices in certain jurisdictions. It also argued that the high mobile termination rates were at least partially responsible for high retail prices which were to the detriment of consumers.

As the Commission Explanatory Note emphasizes (European Commission 2009b: 16):

“Above-cost termination rates can give rise to competitive distortions between operators with asymmetric market shares and traffic flows. Termination rates that are set above an efficient level of cost result in higher off-net wholesale and retail prices. As smaller networks typically have a large proportion of off-net calls, this leads to significant payments to their larger competitors and hampers their ability to compete with on-net/off-net retail offers of larger incumbents. This can reinforce the network effects of larger networks and increase barriers to smaller operators entering and expanding within markets.”

In reality, the relationship between MTRs and retail prices is complex. There are many other factors that can explain a change in retail prices and there is little evidence to suggest that lower MTRs necessarily or directly lead to lower retail prices. However, MTRs do act as a price floor for off-net calls, thereby creating a barrier for operators to compete for each other’s customers. This means that high MTRs are likely to weaken competition and therefore, indirectly, lead to higher retail prices. Furthermore, experience in Europe undermines the case for the converse argument (the waterbed effect) which suggested that operators would compensate for the loss of revenue from MTRs by increasing retail prices. With the decline and fall of MTRs in Europe, especially after the introduction of pure LRIC (2012), mobile operators started competing with low tariffs and with no differentiation between on-net and off-net prices. Many of these tariffs were integrated into bundles that added other services, such as fixed telephony, fixed broadband, and pay television. So, while it is difficult to prove that low MTRs caused low retail prices, most certainly the reduction in MTRs was a necessary condition for these consumer-enhancing developments to occur, particularly through ubiquitous bundles.

Termination Eurorates

The European Electronic Communications Code (EECC) (European Union 2018) of December 2018 builds on earlier EU recommendations and emphasizes the importance of harmonization across member states. To this end, mobile termination rates are to be set on the basis of a single bottom-up cost model using current costs, pure LRIC, economic depreciation, and an efficient operator with market share not less than 20 per cent.

However, the EECC goes further in that it requires a single EU-wide maximum call termination rate (“Eurorate”) to be established by December 31, 2020 (European Union 2018: Article 75). To achieve this the European Commission has constructed a unified cost model to determine the costs of call termination in a harmonized manner. The results of the model have been consulted upon, firstly via the national regulatory authorities and then through a wider public consultation in 2019 to determine:

- In which countries and in what circumstances deviation from the Eurorate might be justified – around half of respondents to the consultation thought that national variations should be allowed.

- In which countries and in what circumstances a glidepath or other transitional arrangements might be justified – 65 per cent of respondents favoured a transition period, primarily for countries whose current termination rate is above the Eurorate.

- Whether the Eurorate could be applied outside the European Economic Area (EEA) by establishing requirements on companies that also operate within the EEA – most respondents thought that this should only happen on a reciprocal basis.

The European Commission will publish its final decision on these matters during 2020.

Endnotes

- Other factors, not covered in this article, were also at play, in particular the migration from voice to data traffic. See also Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “How the growth of data traffic affects interconnection charges.” ↑

- Under the CPP arrangement, the calling party (and not the called party) pays the total price of a retail call. This means that the voice call termination charge is included in the originating network provider’s (either fixed or mobile) cost base and is reflected in the retail price it sets for calls originating on its network. ↑

- In this article only mobile-to-mobile interconnection is addressed. ↑

- Network effects, also referred to as network externalities, occur when the value of a network to its subscribers increases as more new subscribers join the network. Where there is a large subscriber network, network effects can form a barrier to enter the market or limit expansion for smaller players already in the market. ↑

- Avoidable costs are the difference between the identified total long-run costs of an operator providing its full range of services and the identified total long-run costs of that operator providing its full range of services except for the wholesale call termination service supplied to third parties (i.e. stand-alone cost of an operator not offering termination to third parties). ↑

- In the standard LRIC implementation the increment used is the total service (i.e. including all voice traffic) which equates to a larger portion of costs. This larger increment creates a larger incremental cost than for pure LRIC where the increment is only dimensioned on that part of the voice service related to call termination. ↑

References

BEREC (Body of European Regulators of Electronic Communications). 2019. Termination Rates at European Level. Brussels: BEREC. https://berec.europa.eu/eng/document_register/subject_matter/berec/reports/8900-termination-rates-at-european-level.

European Commission. 2009a. European Commission Recommendation on the Regulatory Treatment of Fixed and Mobile Termination Rates in the EU. 2009/396/EC. Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009H0396&from=EN.

European Commission. 2009b. Explanatory Note: Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the Commission Recommendation on the Regulatory Treatment of Fixed and Mobile Termination Rates in the EU. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/ia_carried_out/docs/ia_2009/sec_2009_0600_en.pdf.

European Union. 2018. Directive Establishing the European Electronic Communications Code. Directive 2018/1972. Brussels: European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L1972.

Oftel (Office of the Telecommunications Regulator). 2003. Director General’s Statement on the Competition Commission’s Report on Mobile Termination Charges. London: Oftel). https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20080715044620/http://www.ofcom.org.uk/static/archive/oftel/publications/mobile/2003/stmt0103.htm.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022