Approach to market definition in a digital platform environment

26.08.2020Introduction

Market definition is both an economic concept and, in many jurisdictions, a legal requirement. It is a necessary precursor of a regulatory finding of dominance (or significant market power, SMP) and thus provides the starting point for determining whether ex ante[1] regulatory intervention is required within electronic communications markets. It is also the initial step for assessing anticompetitive behaviour and merger control within the remit of competition law.

Competition authorities and courts are increasingly concerned with the market power achieved by the large digital platforms. Several countries have strengthened merger control rules and many abuse cases that involve digital platforms are being investigated. With the emergence and substantial relevance of digital platforms, and because of its two-sided[2] nature, the market definition process, as it has been applied to conventional markets, is being contested. Loose market boundaries, highly dynamic markets and bundling of services, among other factors, contribute to doubts about the adequacy of existing methodologies used in market definition to deal with new digital business models. A recent report from the Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE) summarized some of the most relevant issues (Franck and Peitz 2019):

“In market environments with two-sided platforms, the question arises whether the relationship between the platform and the respective market sides can be considered separate markets or whether there is a single market. There is also the issue as to whether there are circumstances under which a market can be viewed in isolation of the other side, or whether the interplay between both sides is always to be taken into account. Another question is how to treat a side on the platform that does not need to make a monetary payment to consume the platform’s service and effectively pays a zero price.”

Are there one or two related markets?

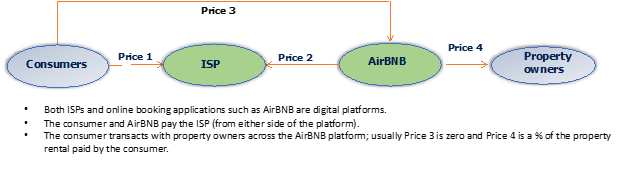

One important issue, when analysing digital platforms, is whether the platform creates one market or two interrelated markets. Some authors (e.g Filistrucchi, Gerardin, and van Damme 2012) make a distinction based on the existence of a transaction. They suggest that in transaction platforms,[3] only one market should be defined, whereas in two-sided non-transaction platforms two interrelated markets need to be defined.

A key reason for defining two separate markets when considering non-transactional platforms is the possibility that a product competes with those of a two-sided platform on one side of the market but not on the other side. For example, there is a market for advertisers on one side of the platform and one for Internet search on the other side. However, for a market characterized by a transaction between two different groups on either side a one-to-one match must occur, and therefore a firm operates in a single market or not at all: the product is the transaction, such as is the case with credit cards.

This suggestion is relevant because, according to one report (Franck and Peitz 2019: 3), it is an approach that has been taken up widely in competition practice and it has been followed in many court decisions.[4] However, the authors disagree with the proposed distinction between transactional and non-transactional platforms. They argue that even on platforms considered to be transaction platforms, transactions are not necessarily observable and that the distinction between a transaction platform and a non-transaction platform is not as straightforward as it seems. Their main conclusion is that a single-market approach when transaction platforms are involved has severe limitations[5] and therefore recommend that courts and authorities should consistently base their analysis on a multi-markets approach. However, it should be noted that when using a multimarkets approach competition authorities and courts still have to investigate interdependencies since market definition on one side of the platform depends on characteristics on the other side.

The European Commission has also recently received proposals on how to deal with digital platforms. A special adviser’s report (Crémer, de Montjoye and Schweitzer 2019) on competition policy for the digital era provided a number of recommendations. The report states that, in the case of digital platforms, less importance should be given to market definition and more emphasis put on the theories of harm and identification of anticompetitive strategies. The authors argue that “in the digital world, it is less clear that we can identify well-defined markets.” According to the report, another problem of market definition arises when a dynamic market environment leads to fluid, fast-changing relationships of substitutability (Crémer, de Montjoye and Schweitzer 2019: 47). In fact, this is not a new idea. Some authors (Evans and Noel 2005) in the past even recommended adopting a looser form of market definition, less based on defining sharp boundaries between markets and giving more consideration to the degree of constraints than is often used in practice. However, the CERRE report disagrees with this approach arguing that the wrong market definition would profoundly impact the assessment of a competition case.

The SSNIP test

The boundaries of any market – the scope of the definition – are always about the limits of substitutability. A standard tool for defining the boundaries of a conventional market is the so-called “small but significant non-transitory increase in price” (SSNIP) test. The test identifies the smallest relevant market through supply- and demand-substitutability of a certain focal product. This is a well-established practice to define a relevant market both in competition inquiries and for ex-ante regulatory definition of relevant markets. The small but significant price increase, which should be above the competitive level, is in the range of 5-10 per cent and non-transitory means the increase lasts for at least a year. If the SSNIP is profitable for a hypothetical monopolist, then the smallest set of substitute products is the boundary of the market (Motta 2004). If not, then the boundaries of the market need to be widened and the test reapplied. Because the SSNIP test implies a price increase by a hypothetical monopolist that produces one product, the application of the test to two-sided digital platforms raises the question of which price the hypothetical monopolist should be raising considering that digital platforms usually set two different prices, one on each side of the platform.

Two-sided platforms economic theory shows us that when a platform owner sets the price on each side generally it takes into account cross-group effects to maximize participation on both sides (Rochet and Tirole 2005). In most circumstances, a price change on one side impacts demand on both sides of the platform, as demonstrated in two of the most influential papers on the theory of two-sidedness (Rochet and Tirole 2003; Armstrong 2005), which analysed the price implications in such platforms. Therefore, in these platforms a key issue is how prices can or should be set on each side of the platform.

For the platform owner, setting the prices correctly is an important aspect of maximizing participation on both sides. Not only the price level but also the price structure determines the demand on each side of the platform. Profit maximization requires price coordination across the different sides: platforms may set prices below marginal cost on one side to attract customers while they charge prices above marginal cost on the other side. A classic example is free admission of women in a night club (ladies’ night) that has also been copied by online dating sites. The club is the platform. Men willing to meet women pay the entrance fee. In this way the platforms is able to balance the number of both women and men and therefore makes it more valuable for both sides.

The socially optimum price on one side of the platform can even be zero. This has important implications if regulatory price intervention is considered. The CERRE report also draws our attention to this feature of platform pricing: the adoption of a multimarkets approach makes it necessary to recognize “zero-price markets” as subject to competition scrutiny by authorities and the courts, and therefore there can be “markets” for products which are offered free of charge. This, in turn, can increase the complexity of the hypothetical monopolist’s test application.

The SSNIP test and zero-price markets

While predatory pricing is an unlawful practice in case of traditional industries, selling a product below marginal cost can be a normal and profit-maximizing strategy in a two-sided market platform rather than an attempt to predate. In these circumstances how can the SSNIP test be used to define markets, and how can truly anticompetitive pricing be detected? A number of approaches have been suggested:

- In the European Commission advisor’s report, the authors suggest that if there is a zero price on one side of the platform, the SSNIP test would need to consider an increase of the price in absolute terms as a percentage increase from zero would still mean zero.

- A recent review (OECD 2018) of antitrust issues suggests that it does not make sense to consider a price increase on the side where the price is zero. However, one could use the SSNIP test starting from a focal product with a positive price and assess if the product with zero price could be a substitute.

- Other authors (Newman 2016) recommended applying the test in a modified way. For example, some suggest that in the case of zero pricing, the SSNIP test could be modified to a cost or a quality-based test. So, another possibility is to focus the substitution analysis on product characteristics such as quality instead of price. One such test has been coined as the SSNDQ test.

The SSNDQ test

The OECD (2013) suggests, for market definition purposes, the adoption of a “small but significant non-transitory decrease in quality” (SSNDQ) test. The SSNDQ test would be used in markets with rapid technological change instead of the established SSNIP test which focuses on prices. But as the European Commission adviser’s report points out, it is not clear how such a test could be applied in practice. As an example, they question what level of degradation in quality would be equivalent to a 5-10 per cent price increase for the authorities or the courts to be able to assess if the hypothetic monopolist would still be profitable. As the OECD states, the usefulness of such a test would be more of a conceptual guide than an objective criterion that could be applied by competition authorities or the courts. An example application of the SSNDQ test is provided in the case of Qihoo 360 v TenCent in the Supreme People’s Court of China (Evans and Zhang 2014).

Conclusions

Digital platforms operate with different types of business models which they adjust constantly in search of better commercial outcomes. For this reason, governments, competition authorities, and industry regulators are now facing an increasingly dynamic ICT environment. Competition issues have become more complex as market definition (and therefore also relevant markets subject to ex-ante regulation) have become less clear and the market boundaries more rapidly changing.

Some experts are advising that in the case of platforms, because market boundaries are difficult to define and change rapidly, less importance should be placed on market definition and more emphasis is placed on the theories of harm and identification of anticompetitive strategies. However, even those experts recognize that (Crémer, de Montjoye and Schweitzer 2019: 45):

“In practice, the difficulties of using the SSNIP test or the SSNDQ test have not been an obstacle to market definition in EU antitrust and merger cases concerning platforms in general, and zero-price services in particular, as the Commission has instead turned to assessing service functionalities.[6] While product and service functionalities have always been the starting point for determining substitutability relationships, they lack the same degree of theoretical rigour that the SSNIP test has introduced; however, they may well be all we have in the case of multi-sided platforms…”

In spite of the methodological problems faced when applying the SSNIP/SSNDQ test, it remains useful, at least as a thought experiment when considering demand-side substitutability. The CERRE report concludes that the SSNIP test is conceptually applicable to two-sided platforms, but cross-group effects and their interplay must be included in the analysis, and the test must be applied on both sides of the platform in order to understand how the platform adjusts its pricing structure.

Endnotes

- Specific telecommunications sector ex-ante regulation has been introduced to foster competition. In many jurisdictions only wholesale markets are regulated whenever an operator holds significant market power (SMP). Anticompetitive behaviour or abuse of dominant position is dealt with ex post under horizontal competition law. ↑

- Platforms can also be multisided, but the same issues arise. ↑

- Two-sided markets of “the payment cards type” are characterized by the presence and observability of a transaction between the two groups of platform users. As a result, the platform is able to charge not only a price for joining the platform but also one for using it, i.e. it can ask a two-part tariff. Hence these markets can be referred to as two-sided transaction markets. Examples include, apart from payment card schemes, virtual marketplaces, auction houses, and operating systems. ↑

- A good example is Ohio v American Express Co. ↑

- Such as “neglecting close substitute offers on one side of the market” (CERRE 2019: 25). ↑

- The practice before the SSNIP test existed. ↑

References

Armstrong, M. 2005. Competition in Two-Sided Markets. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/14583/1/14583.pdf.

Crémer, Jacques, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye, and Heike Schweitzer. 2019. Competition Policy for the Digital Era. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/reports/kd0419345enn.pdf.

Evans, D.S. and M.D. Noel. 2005. “Defining Antitrust Markets When Firms Operate Two Sided Platforms.” Columbia Business Law Review (2005) 3. https://www.noeleconomics.com/articles/NOEL_defining.pdf.

Evans, David S., and Vanessa Yanhua Zhang. 2014. “Qihoo 360 v Tencent: First Antitrust Decision by The Supreme Court.” Competition Policy International, October 20, 2014. https://dev.competitionpolicyinternational.com/qihoo-360-v-tencent-first-antitrust-decision-by-the-supreme-court/.

Filistrucchi, L., D. Gerardin, and E. van Damme. 2012. Identifying Two-Sided Markets. Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche Università degli Studi di Firenze, Working Paper N. 01/2012. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228230981_Identifying_Two-Sided_Markets.

Franck, J., and M. Peitz. 2019. Market Definition and Market Power in the Platform Economy. Brussels: Centre on Regulation in Europe(CERRE). https://www.cerre.eu/sites/cerre/files/2019_cerre_market_definition_market_power_platform_economy.pdf.

Motta, M. 2004. Competition Policy: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newman, J. M. 2016. “Antitrust in Zero-Price Markets: Applications.” Washington University Law Review 94 (1). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2681304.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2013. The Role and Measurement of Quality in Competition Analysis. Policy Roundtables. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/competition/Quality-in-competition-analysis-2013.pdf.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2018. Rethinking Antitrust Tools for Multi-Sided Platforms. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/Rethinking-antitrust-tools-for-multi-sided-platforms-2018.pdf.

Rochet, J. C. and J. Tirole. 2003. Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets. Toulouse School of Economics. http://idei.fr/sites/default/files/medias/doc/wp/2002/platform.pdf.

Rochet, J. C. and J. Tirole. 2005. Two-Sided Markets: A Progress Report. Toulouse School of Economics. https://www.tse-fr.eu/sites/default/files/medias/doc/by/rochet/rochet_tirole.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022