Competition and economics

15.12.2020Introduction: Regulatory transformation in the digital economy

Over the past 10 years there has been significant market and regulatory disruption caused by digital transformation. This disruption, which is set to continue, extends to almost all corners of the economy, and is primarily the result of a transition to data-centric business models based on digital platforms (ITU 2020a).

Digital platforms are embedding market power and, in a race for scale and scope, leading to transnational markets. This means that regulation is increasingly beyond the scope of individual national regulatory authorities (NRAs).[1] Elsewhere, NRAs have to work in regional collaboration if they are to be effective. This may be done through supranational organizations and regional organizations (e.g. European Commission) or by individual NRAs building on the work of others that have taken a lead on platform and content regulation. Regulators in microstates face particular challenges[2] as the national market lacks the scale to maintain competitive supply models, and they may lack the resources (mainly in terms of readiness and human capacity) to regulate the dominant supplier.

Legacy national services still exist, and traditional regulation of services and prices will continue for some time, but the need for such regulation within national borders is in decline. This is because traditional services are constrained by over-the-top (OTT) applications on transnational digital platforms. Traditional approaches to regulation are in any case coming under increased pressure because of digital transformation:

- Market definition and analysis is made more difficult by convergence of fixed/mobile, voice/data and traditional/OTT services. The typical regulatory process also takes too long to be effective in markets that are rapidly developing, and the whole market analysis process strains the resources of many regulatory authorities. A simplification of the market analysis process is urgently needed so that it can be delivered in a timely manner while being robust enough to withstand legal challenge.

- Interconnection remains vital where multiple networks coexist, but termination rates can be simplified – set at or close to zero – often without the need to apply costing methodologies and models.

- Licensing will increasingly be achieved via general authorisation for service provision and symmetrical ex-post regulation, i.e. rules that apply to all service providers not just those with significant market power (SMP). For example, regulators should check for anticompetitive bundling of services practices, and limit mergers and acquisitions that have the potential to lessen competition substantially. New competence and, potentially, new competition agencies are needed if this regulatory transition is to be effective.

Although operating as transnational markets, all digital platforms and services still need access to national infrastructure for delivery and customer engagement. The focus of NRAs should therefore be on ensuring this access is available with sufficient capacity, at acceptable quality of service (QoS) and on fair terms.

The ever-increasing demand for data puts pressure on national network infrastructure, especially access networks. The investment requirements to provide adequate bandwidth may be incompatible with competition (especially in least developed countries, landlocked developing countries, small island developing states and also in rural and isolated areas). Licensing requirements and conditions attached to state funding become key. National regulatory authorities should also explore partnership models in which digital platforms share the cost of national ICT infrastructure (with a need to revisit the use of the concept and principles of network externalities).

Setting access network requirements at the right level requires cost modelling and business plan analysis of network roll-out (ITU 2019a). Regulation is about monitoring progress against pre-determined key performance indicators (KPIs). The ability to impose sanctions and remains essential, although fines are never satisfactory.

More generally, extracting value from digital platforms at a national level requires adaptation of taxation policies – potentially based on subscriber numbers and revenues rather than profits. Money raised should be used to fund network deployment and improvement of access – either directly or via an alternative funding mechanism for digital development – in order that the digital economy can be further developed.

Regulation in the digital era

Historical approach

Before digital disruption, telecommunication networks, services, and markets were primarily national in scope and for the provision of a limited and standardized set of telecommunication services to end users. Most countries had moved well beyond the limitations of monopoly supply, offering some degree of competition and consumer choice. However, until recently, the supply of telecommunication services was largely a one-way transaction in a single-sided market.

Under the auspices of NRAs, controlling a quasi-competitive market, the supply chain was split into wholesale and retail components. Wholesalers were subject to economic regulation especially where they controlled bottleneck facilities or had SMP. Retailers were generally not regulated or lightly regulated (except for consumer protection[3]), because effective competition could arise based on equal access to wholesale inputs.

Recent developments

Two-sided and multisided digital platforms (e.g. Facebook, Google) have emerged and grown rapidly. Their appeal to customers is based on offering innovative services which appear to cost them nothing (or very little). Purely in terms of price this is true, but the business model of digital platforms relies on customer data (albeit often anonymized and aggregated) to create value that can be monetized on another side of the platform (e.g. to advertisers or content providers). Digital platforms thus act as a marketplace, bringing together and reducing transaction costs between distinct groups of customers.

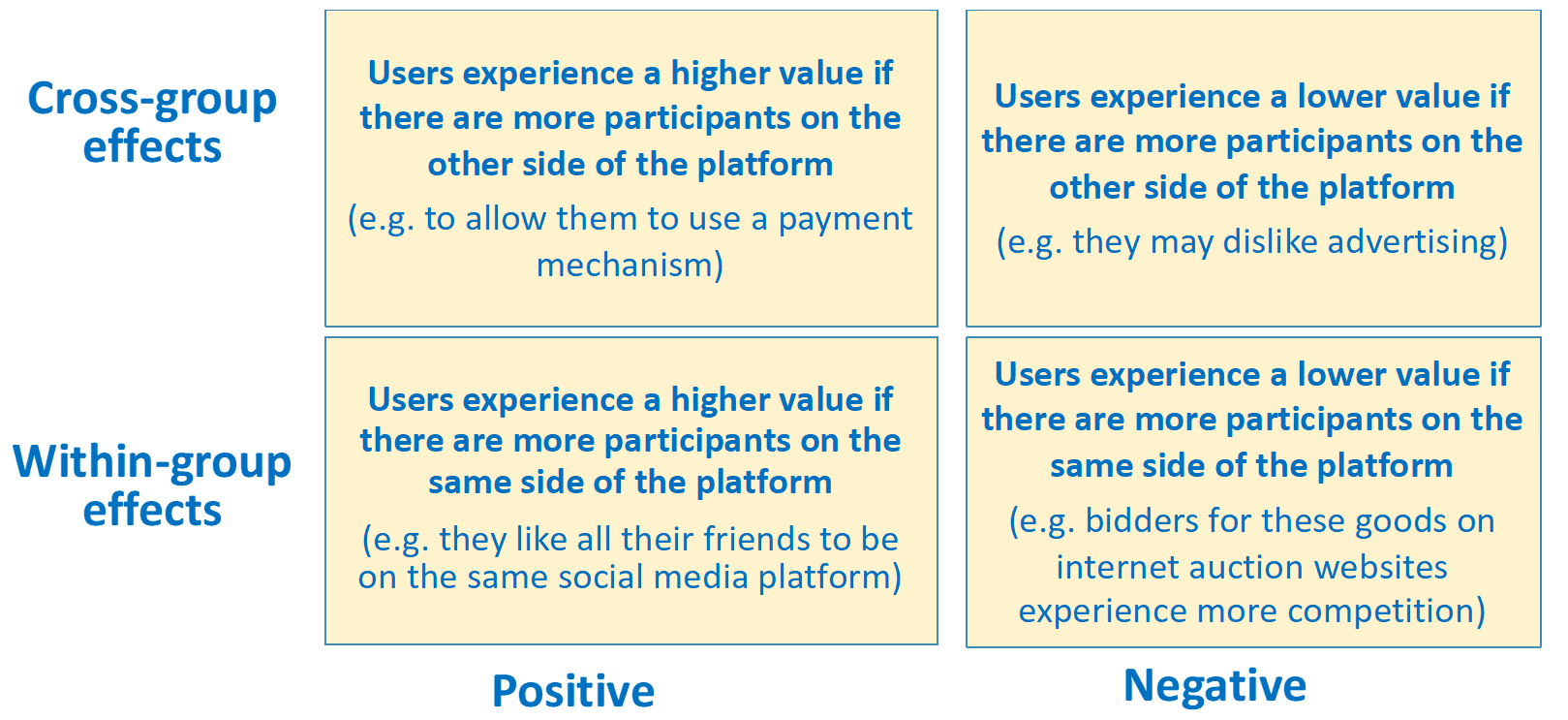

There are strong network externality effects at play.[4] Network effects describe the impact that an additional user of a service has on the value of that service to others. These externalities can be on one side of the platform or across the platform; they can be positive or negative. If the platform is transactional (i.e. where it enables transactions between customers on either side of the platform) this strengthens externalities.

Figure 2.1. The network effects of digital platforms

Source: ITU 2018a.

Overall, strongly positive cross-group externality effects for digital platforms have led to:

- A race for scale. Scale is critical to enhance service and to lower costs. There are strong first-mover advantages, and established platforms frequently acquire start-up rivals to protect their predominant position.

- A concentration of market power. It is difficult for smaller platforms to compete as they have higher costs and cannot readily match the consumer value of more ubiquitous platforms.

- Transnational and global markets. The more global a platform’s reach the greater the network externality effects.

- The fracturing of traditional telecommunication network regulation. Operating outside of the traditional regulated space, and across national boundaries, digital platforms nevertheless compete with and, in some cases, undermine telecommunication network service providers (e.g. OTT service providers have greatly impacted the traditional revenues of telecommunication network providers).

Each of these outcomes could be problematic for economic regulation. They have led to a situation in which:

- Digital platforms are borderless: too large and too wide to regulate;

- Market concentration is excessive: competition is so limited that there are de facto monopolies;

- Consumer data funds the system in non-transparent and potentially harmful ways;

- Digital platforms are not making a consistent and proportionate contribution to the national infrastructure that they depend upon.

But consumers do not generally complain. They like the services offered and the low or zero price. Even if consumers have concerns about how their personal data is being used, they are willing to accept (generally without reading) whatever terms and conditions the platform providers impose. This is where regulation must step in: to provide safeguards, monitor operations, and enforce sanctions if needed.[5]

Net neutrality is one area of regulation that has received a lot of publicity. The term “net neutrality” refers to the equal treatment of all data packets, regardless of application, user or price. The key principles have been summarized (FCC 2015) as:

- No blocking: network operators may not block access to legal content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices;

- No throttling: network operators may not impair or degrade lawful Internet traffic on the basis of content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices;

- No paid prioritization: network operators may not favour some lawful Internet traffic over other lawful traffic in exchange for consideration of any kind – in other words, no “fast lanes”. This rule also bans ISPs from prioritizing content and services of their affiliates.

The ongoing challenge for telecommunication network operators is to provide sufficient bandwidth to support all the applications that the Internet offers and users demand. They are severely constrained in the end-user price that they can set, so they may seek payment from the other side of the market. However, the market power of digital platforms is now so great that the network operator may be unable to extract further revenue. Thus, starved of money on both sides of the market, it may seek instead to block content or throttle demand or prioritize paid traffic simply to cover its costs.

Although the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) later reversed its decision (FCC 2018), the principles that it espoused in 2015 continue to guide regulators elsewhere. For example, the equivalent European Regulation (EU 2015) requires that , “Providers of internet access services shall treat all traffic equally, when providing internet access services, without discrimination, restriction or interference, and irrespective of the sender and receiver, the content accessed or distributed, the applications or services used or provided, or the terminal equipment used,” although this does not prevent implementation of “reasonable traffic management measures.” [6]

In effect, net neutrality principles have been established not as ex-ante regulation, but as a guide for ex-post intervention on a case-by-case basis as required. One article[7] explains that:

“Broadband access providers and internet content providers are in a symbiotic relationship – each feeds off the other, requiring the other to help it generate revenues and profits. In economic terms, the presence of increasingly powerful internet content providers is providing the necessary countervailing buyer power to curb the dominance of incumbent access providers in national markets, while the demands of a two-sided market mean that the content providers cannot afford to exploit their economic power to the detriment of the organisations that connect them with the very end-users that are the source of that power. The future role of the regulator is going to be much more one of monitoring agreements rather than intervening to set prices or determine quality of service levels. Net neutrality rules are therefore primarily guidelines for ex-post resolution of disputes – which is exactly what the FCC’s Open Internet Order suggested.”

In Europe, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications issued guidelines to national regulators on the implementation of the net neutrality rules (BEREC 2016) and has subsequently reported each year on the application of the guidelines, with particular emphasis on emerging 5G technologies in relation to net neutrality.

Key findings

- The regulation of traditional networks will continue – although network operators may be small vis-à-vis digital platform providers, they still control access to the customer – but regulation needs to focus on infrastructure access so as to continue being relevant and effective.

- Regulators should be wary of authorizing digital platform providers to construct network infrastructure to avoid leverage dominance into the market for network access, but ways should be sought to ensure that digital platforms contribute to the costs of deploying and maintaining access infrastructure.

- Regulation should increasingly be conducted ex post, focused on monitoring agreements and resolving disputes between telecommunication network providers and digital platforms, based on clear principles such as those of net neutrality.

- NRAs must collaborate with one another and with competition authorities to ensure consistent and effective regulation of digital platforms. In these matters the regional/international bodies such as the ITU and Regional Regulatory Associations[8] will play a lead role to ensure coordinated, concurrent regulation. NRAs in developing countries might also build on the work of others that have taken a lead on platform and content regulation, e.g. on the approach to digital platform regulation taken by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) in Australia[9] and the work on regulation of OTT services in India.[10]

The regulation of markets

Historical approach

Economic regulation has traditionally been based on a market analysis procedure that comprises three parts:[11]

- The definition of markets. From a regulatory perspective markets are defined on the basis of demand and supply substitutability, with the boundaries of a market based on behavioural responses to a small but significant non-transitory increase in prices (SSNIP) by a hypothetical monopolist providing a single focal product in that market. Markets have by default generally been defined on a national level (occasionally with regional variants).

- The assessment of dominance or significant market power (SMP). Although many economic factors are involved in creating or sustaining a dominant market position, much legislation and most regulatory practice has focused on an assessment of market share (usually revenue-based) as this is the most easily quantified and validated measure. Regulators sometimes assess a range of other relevant factors, such as market concentration, access to finance, economies of scope, technological advantage, and the prospect of countervailing buying power.

- The imposition of proportionate remedies. Remedies are imposed ex ante on SMP suppliers in order to prevent them engaging in anticompetitive practices that, absent regulation, they might reasonably be expected to practise. The remedies that are chosen should be the least intrusive remedies that adequately address the specific competition concerns identified. The major categories of commonly imposed remedy are:

- An obligation to supply

- Non-discrimination

- Transparency (e.g. publication of reference offers)

- Cost-based pricing.

Ex-post remedies are also available if and when specific anticompetitive practices are identified (e.g. predatory pricing, exclusionary behaviour, tying and bundling).[12] The market analysis process to be followed is similar to that for ex-ante regulation: the aim is to impose proportionate remedies on SMP suppliers. However, ex-post regulation requires the regulator to prove that some behaviour has had anticompetitive effect or intention, and then to impose remedies that will remove and recompense for any harm caused.

Moldova provides a good example of market analysis, which shows how the NRA was able to build on the solid foundations laid down in its first round of market analysis so that subsequent updates followed a streamlined but robust process.[13]

Recent developments

The rise of digital platforms and the consequent increase in competition from service providers independent from telecommunication network operators, has radically altered the landscape in which regulators attempt market analysis. In particular:

- Markets can no longer be presumed to be national in scope; and market analysis is harder for NRAs who cannot demand or easily obtain relevant data from global players.

- Market definition is complicated by the presence of two-sided digital platforms[14] – is there a single market covering both sides of the platform or two different markets?

- The SSNIP test is hard to use in markets where services are often zero-rated, bundled, or have usage-independent prices. Which price should be raised? What constitutes a SSNIP when the base price is zero?

- One dominant player in a market may no longer be an undesirable (or avoidable) state of affairs. One platform with high market share may be the welfare-maximizing market structure reflecting high network effects. An explosion in demand for data leading to large-scale network investment may be, in many cases, incompatible with competitive market models.

- SMP designation (and regulatory remedies) therefore needs to be based on a much broader range of indicators (e.g. service differentiation, congestion, access to data, innovation, barriers to entry, and barriers to expansion.)

- Many behaviours previously considered anticompetitive are now part and parcel of legitimate business models, e.g. some pricing below marginal cost and some tying of services are common features of digital platforms. There will still be genuine concerns about predatory pricing and exclusionary behaviour, but they will be much harder to detect and prove.

Key findings

- Traditional ex-ante regulation based on market definition, dominance, and determination of remedies will continue to be important specifically for the regulation of network infrastructure access.

- More generally, there will be refocusing of competition regulation with a transition to ex-post symmetrical regulation (the same rules applied to all suppliers) with regulatory intervention targeted at specific cases of competitive harm, and with high levels of cross-sectoral regulatory cooperation.

- These changes are necessary because:

- The traditional focus on SMP-based regulation was intended to enable others to compete fairly but digital platforms, access networks, and even entire national broadband networks, may now sometimes be best delivered as virtual monopolies;

- Even where competition exists it is increasingly hard to define markets, determine thresholds for SMP, and determine and apply appropriate remedies;

- Under the current regime, some cross-border operators are too big to fail and/or too large to challenge – they can and do act with regulatory impunity.

- Symmetrical regulation will be based on broad regulatory principles such as fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory access to resources.

- For ex-post regulation to be effective, countries need to establish and adequately resource separate competition authorities (or assign equivalent powers to the NRA).

Interconnection of networks

Historical approach

Any-to-any connectivity was a fundamental requirement in newly liberalized telecommunications markets, ensuring that all users could connect with each other regardless of network operator.[15] Interconnection between competing networks was therefore essential and, because of the imbalance of power between incumbents and new entrants, commercial negotiation could not produce fair, reasonable and procompetitive outcomes.

The principle of regulated interconnection was extended to include wholesale access to any technically or commercially feasible component of an incumbent or SMP operator’s network. The aim was to create a “level playing field” in which new entrants could choose, without prejudice, between building their own infrastructure and renting from the incumbent, through either access or interconnection. Given this regulated access to necessary wholesale inputs, new entrants could replicate the retail offers of the SMP provider.

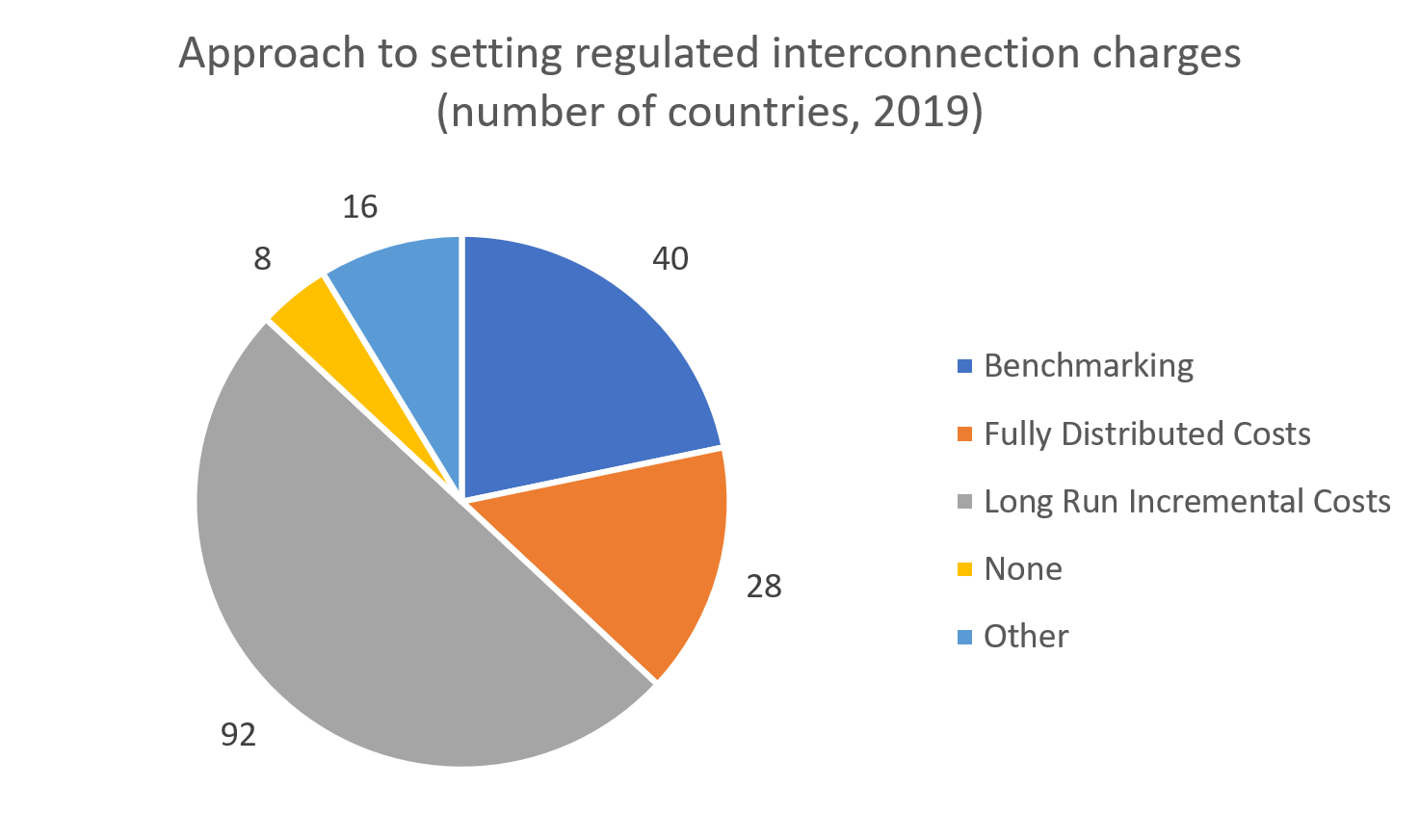

For the entrant’s build-or-buy decision to be neutral, regulated access and interconnection charges had to be cost based. Much thought and effort went into determining the most efficient cost-standard to be used, gradually settling on the use of long run incremental costs with a mark-up for common overheard costs (LRIC+). Most regulators constructed their own cost models bottom-up (i.e. simulations of actual networks based on efficient economic and engineering practices), giving rise to the acronym BU-LRIC+ as the widely adopted cost-standard. However, in some places (most notably the European Union[16]) even lower rates, based on “pure LRIC” were used for call termination. Pure LRIC represents the difference in total costs with and without the supply of the termination service, divided by the number of call termination minutes.

Figure 2.2. How cost-based interconnection prices are set

Source: ITU.

Recent developments

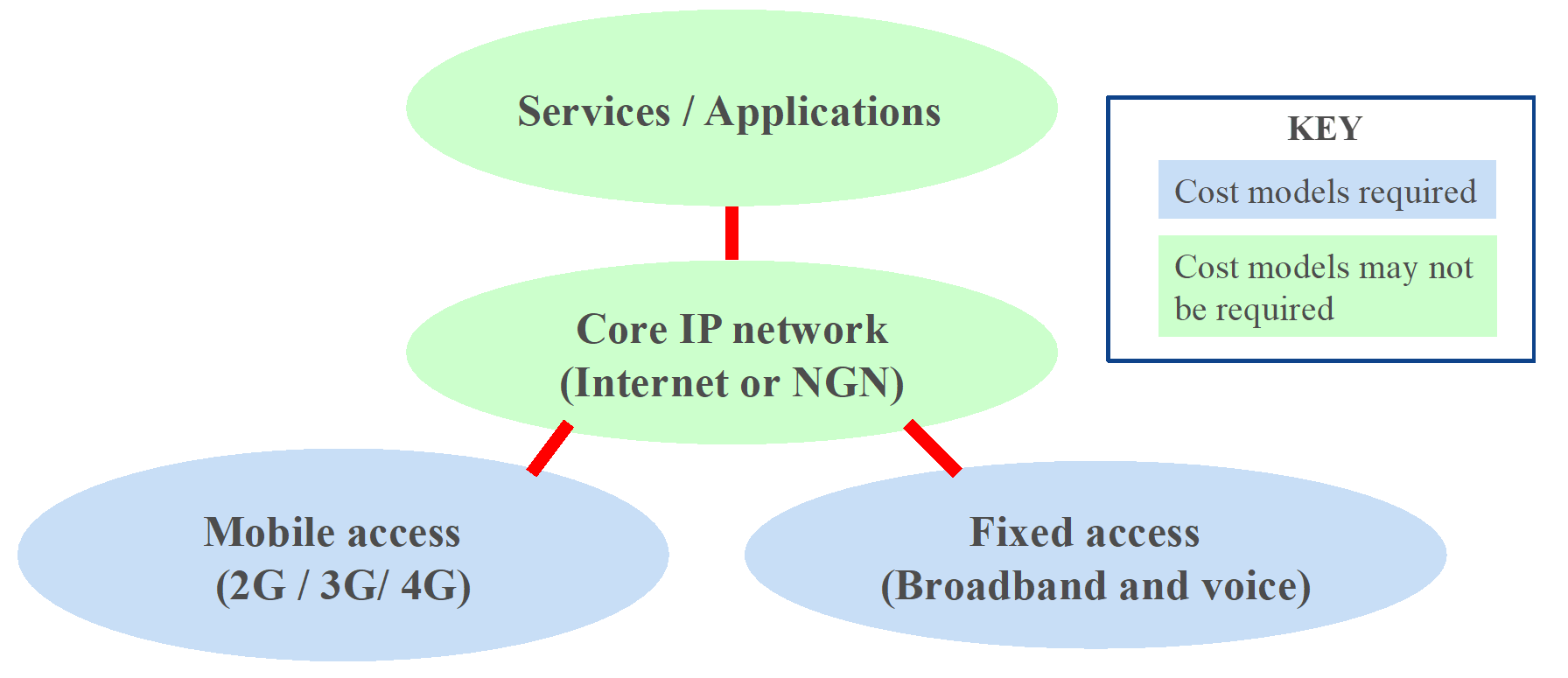

Data-centric networks, based on the Internet Protocol (IP) have radically changed the service supply chain, affecting costs and prices, and requiring a rethink of traditional regulatory practices. The tendency in IP networks is to have fewer network nodes, centralized service functionality, and multiple transmission paths used for the same communication. All of this results in high-fixed and low-variable costs, thus making usage-based charges somewhat theoretical.

The transition to IP networks affects the fundamental requirement for cost-based regulation, especially for interconnection services. The IP world is dominated by data traffic: voice is a diminishing and insignificant part of the overall network capacity, so cost-based voice termination is of marginal significance.[17] Regulatory cost models for the core IP network may not be needed at all; as competition thrives, there is potentially less SMP and less need for ex-ante regulation.

As the need for regulated cost-based interconnection is reducing, so the need for regulated cost-based access is increasing. Application providers require open access to digital infrastructure, as it is only through that infrastructure that they can reach their customers. In many cases, especially for bandwidth-intensive applications such as video, they require access to high-capacity infrastructure. This requires investment on the part of the access provider (e.g. fibre roll-out for fixed networks or 4G/5G mobile technology) that will need to be recovered either directly from the customer or via the application service provider.

Figure 2.3. Regulatory cost models should focus on access prices

Source: ITU, 2019b.

Key findings

- Effective ICT policy and regulation will need to pave the way for the deployment of very high capacity networks (VHCNs) such as fibre, Data Over Cable Service Interface Specification (DOCSIS) cable, and 5G mobile. The timing of the deployment will vary by country.

- There are two basic models for achieving this:

- Whichever model is used, access prices must be regulated so as to reward investment in VHCNs but also to encourage reuse and sharing of passive infrastructure wherever possible (see the “Infrastructure sharing” section below and ITU 2018c) and ensure affordability.

- BU-LRIC+ pricing remains valid, but more emphasis should be placed on access to infrastructure and much less on voice call termination. For example, in the European Union, voice termination charges are now being set on the basis of “Eurorates” – standard cost-based rates applicable across all Member States.[20]

Infrastructure sharing

Historical approach

In the early days of liberalization there was persistent debate about the merits of facilities-based competition and services-based competition. The former prioritized the competitive supply of infrastructure, even if it resulted in less consumer choice in terms of service providers. The cost of duplicating infrastructure was considered to be small relative to the consumer benefits of choice and innovation that would flow from competitive supply models. The United Kingdom and the United States in the 1980s and 1990s were prime examples of countries that gave priority to facilities-based competition.

Even where facilities-based competition was promoted, regulators soon realized that the barrier to market entry was high, and the “ladder of investment” theory was proposed (Cave 2006). The idea was that if various forms of infrastructure access were possible, then investors would be able to choose their entry point and then to increase their investment step-by-step until they became full facilities-based operators. This required access at every technically and commercially feasible point in the network, to provide a full suite of different infrastructure sharing options including passive (civil engineering) assets, active electronics, and radio frequency spectrum.

Recent developments

The need for infrastructure sharing has become greater as the investment required to construct and maintain broadband digital infrastructure has increased. Just as the transformation towards a digital economy was taking shape, the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 curtailed the availability of investment funds; and a similar dynamic is being felt today as the need for 5G mobile and Internet of Things (IoT) investment is juxtaposed with the global recession emerging as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

Infrastructure sharing is therefore likely to be a permanent feature of the telecommunications landscape. There is a global trend towards permitting infrastructure sharing and, in many cases, mandating the sharing of bottleneck elements in the supply chain: local loops, ducts, towers, and sites. A good example is provided by Brunei Darussalam in which all fixed and mobile networks have been merged into a single new entity, to which all service providers have equal access.[21] More usually, there will not be common ownership of assets, but there remains the need for open and non-discriminatory access to shared infrastructure (e.g., to the submarine cable in the Seychelles).

In most jurisdictions, the terms of infrastructure sharing are set through commercial negotiation, but regulators may publish guidelines and may be required to resolve disputes (see section on “Dispute Resolution” below). Best practice principles for infrastructure sharing regulations include:[22]

- The regulatory framework should apply to all sector participants.

- All types of sharing should be permitted as long as competition is not adversely affected.

- All sector participants should have the right to request to the sharing of infrastructure that has been mandated for sharing.

- All sector participants when requested are obliged to negotiate sharing of their (mandated) infrastructure.

- Operators designated as having SMP in a passive or active infrastructure market are required to publish a reference offer approved by the NRA.

- Commercial terms for infrastructure sharing should be transparent, fair/economic and non- discriminatory.

- The approval process for new infrastructure should be timely and effective and should encourage infrastructure sharing.

- Dispute resolution process should be cross-sector, documented, timely, and effective.

- The infrastructure sharing regulatory framework should take into account the national broadband plan, universal access and service fund (UASF) policy, and future technology development.

Key findings

- The digital economy requires a scale of investment and a geographical reach that precludes the possibility of full facilities-based competition. This makes infrastructure sharing a regulatory prerogative.

- Prices for infrastructure sharing are best set through commercial negotiation so that they embed a commercial rate of return on investment; but regulators need to have oversight of the terms and conditions so as to ensure that infrastructure owners do not abuse their dominant market position.

- All service providers, including the digital platforms that most require high-capacity infrastructure, should contribute proportionately to the cost of that infrastructure through the payment of appropriate regulated access prices.[23]

Price regulation

Historical approach

Before market liberalization, governments set all prices for telecommunications services as part of the annual budget.[24] The range of services was limited, prices varied little from year-to-year and were generally high because telecommunication was a revenue source.

After liberalization governments sought to expand the sector through competition and to collect revenue from the sector primarily through “Licensing and authorization” and “Taxation” (see sections below). Price controls were then focused at the wholesale level (see “Interconnection” section) while retail price regulation was relaxed – just how much depended on the extent of competition, but generally the focus was on SMP providers. The key regulatory discipline was forbearance: intervening only where necessary to prevent excessive prices or anti-competitive prices.

Typically, regulators have deployed two standards of retail price regulation:

- Price approvals – in which formal approval from the regulator is needed before going to market. Price approvals are best applied only to significant tariffs of licensees that have a dominant market position for the service in question. Unless there are reasonable grounds to oppose a tariff, the regulator should approve tariffs expeditiously so as not to undermine the proper functioning of the market.

- Price notification – in which tariffs are submitted to regulator for information purposes only. This approach is appropriate where the service provider does not have SMP, where the service in question is of relatively minor significance and for short-term promotional offers.

The tariff regulations in Iran[25] provide a good example of these procedures.

Recent developments

The aim of traditional retail price regulation has been to limit interventions to those situations where suppliers with SMP might otherwise exploit their market position to the detriment of consumers. However, with increasing direct and indirect competition from unregulated digital platforms, retail tariffs of all telecommunication providers, even those with SMP, are severely constrained.

The role of price regulation is therefore changing – it is now more concerned with ensuring fair competition amongst facilities-based service providers rather than protecting end users directly. The regulatory risk is not in overcharging, but in predatory pricing that leads to underfunding of network development. Broadband service pricing is complex (affected by factors such as the average or minimum download and upload capacity, usage caps, and contract duration) and this gives dominant suppliers more opportunities for anti-competitive pricing (e.g. by tying customers to long-term contracts or failing consistently to deliver the advertised upload/download speeds).

Also, in order to meet the challenge of OTT service providers, telecommunication network operators are increasingly using zero-rating, and bundled tariffs (e.g. for “quad-play” combining broadband Internet access, television, fixed-line telephone, and wireless service) and making greater use of price-promotions to circumvent legacy regulatory price controls. Many of these developments are positive for consumers and need not result in regulatory interventions. However, regulators need to check for practices that spill over into anti-competitive behaviour.[26]

Key findings

- Regulators should generally take an active monitoring or “watching brief” attitude to retail price regulation: intervention will be principled but ex post.

- Ex-post regulatory intervention in response to complaint or concern may be sufficient for most situations (e.g. of predatory pricing or margin squeeze).

- Service providers should regularly file data on subscription numbers, service tariffs, and volumes so that the regulator can act quickly where necessary.

- A specific focus should be on entry-level products (especially for Internet access) to ensure affordability, including zero-rating where it does not unduly distort service competition.

- As the costs of supplying Internet access are higher in some countries (e.g. those that have low population density, are islands or are landlocked) (A4AI 2018, s4.2), it is important to adopt policies that help to reduce those costs (e.g. through public investment, targeted subsidies, or tax breaks) so as to improve Internet access and affordability.[27]

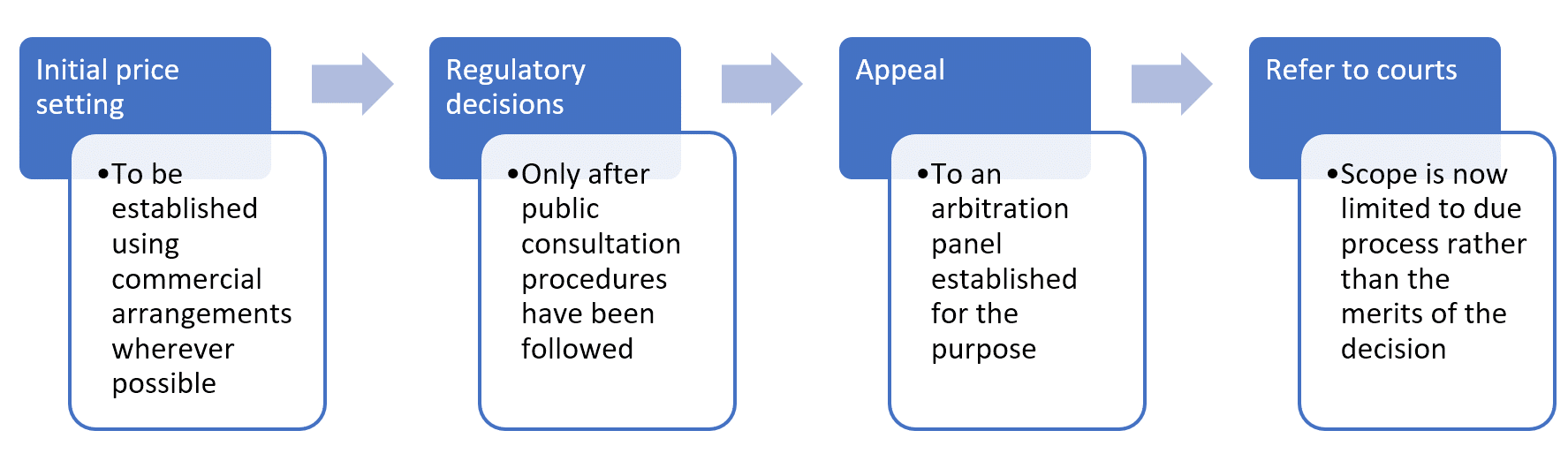

Dispute resolution

This section refers to disputes between operators with a specific focus on interconnection and pricing disputes.[28]

Historical approach

The national ICT regulatory authority often has a statutory responsibility for resolving disputes between licensees, as described in Chapter 1 on “Regulatory governance and independence”.[29] The World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Basic Telecommunications (WTO 1996) requires member countries to establish an independent body for dispute resolution, and typically those responsibilities are invested in the regulator. Generally, rather than imposing outcomes that might be subject to legal challenge, regulators have sought to mediate in disputes between operators to achieve an outcome acceptable to all parties.

The main reasons for adopting alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are to avoid the high costs, uncertain outcomes, and delays inherent in court proceeding. In some cases where a decision taken by the regulator gives rise to a dispute, the effective final arbiter is an independent body (e.g. the ICT Appeals panel in Papua New Guinea or the Communications and Multimedia Appeals Tribunal in Kenya).[30] However, in some cases the stipulated process is so similar to a formal court that there are few if any savings in terms of cost, time, and regulatory certainty.

While alternative dispute resolution can be preferable to formal legal proceedings, it is far better to avoid disputes altogether. Transparent processes (e.g. public consultations), reasoned statements and the use of external advisors have helped to resolve many disputes.

Figure 2.4. How to mitigate the risk of interconnection/pricing disputes

Recent developments

The telecommunication sector is highly litigious: there are many high-value disputes, but relatively few of them enter into any form of formal dispute resolution. A recent study by Queen Mary University of London (QMUL 2016) found that disputes within the telecom sector were of higher frequency and greater value than in other sectors, and that telecommunication companies have a tendency to prefer litigation rather than arbitration for resolving disputes. A recent case in the Netherlands demonstrates the tendency to use litigation in cases concerning competition and access pricing. The case saw the highest court in the Netherlands overthrow a decision of the national regulatory authority that had determined joint dominance and required cost-based access to the two main fixed network operators.[31]

Despite the proclivity for litigation, arbitration has several key features that make it particularly suitable for dispute resolution in the telecommunication sector:

- Enforceability – the parties agree from the outset to accept whatever is the outcome of arbitration;

- Avoiding foreign jurisdictions – this is especially useful for disputes involving international businesses, such as digital platforms;

- Access to expert decision-makers – with arbitration the decisions will generally be made by a panel deemed acceptable to the parties and comprising the requisite legal, economic, and technical expertise;

- Confidentiality – in some cases, even the fact that there was a dispute may be deemed confidential; in others, the outcome may be published without all the details being made public.

As a result of these features, 82 per cent of industry respondents in the Queen Mary University survey believe that there will be an increase in the use of international arbitration in the years ahead (QMUL 2016, 25).

Regulators have recognized that they have a key role to play in encouraging greater use of arbitration. For example, in the United Kingdom only disputes involving an SMP operator will normally be heard by the regulator, Ofcom, with all other disputes referred for alternative dispute resolution. Ofcom will formally open a dispute only after its scope has been agreed and the parties submit statements indicating that best endeavours have already been used to resolve the dispute through commercial negotiation.

Key findings

- A formal process of arbitration should be set up as an alternative to litigation, covering matters related to competition, interconnection, access, and tariffs. In some countries disputes may be referred directly to the arbitrator, although others may prefer that disputes are first submitted to the communications regulator. In both cases the arbitrator should hear appeals against decisions reached by the communications regulator.

- Arbitration procedures are especially important in developing countries where the expertise of the courts (and, indeed, of the regulator itself) may be less than that of the operators or service providers who are party to the dispute.

- In larger and more developed markets it may be preferable to use a national arbitration procedure, which means that the arbitration will itself be subject to national legislation and gives the ability for parties to challenge the decision in local courts if necessary. If national arbitration is pursued, international companies such as digital platform entities should be required to participate in the arbitration process as a condition of having access to national populations.

- In smaller and developing countries, international arbitration is likely to be preferable and will be more easily agreed upon by international companies. In these cases, care should be taken to ensure that the “seat” of the arbitration is in a country that has ratified the New York Convention, an international treaty providing reciprocity of enforcement of arbitration awards.

Licensing and authorization

Historical approach

Licensing has been widely adopted in the telecommunications industry as a rational means of selecting suppliers for a market with high barriers to entry but which, behind those barriers, was prospectively competitive.[32] Licensing a limited number of suppliers enables governments to attract private-sector investment in infrastructure and services. Licences provided the regulatory certainty needed for investment, while also providing a vehicle to enact public policy goals (e.g. on network coverage, quality of service, or price).

However, in some countries licensing came to be seen more as a means for the government to raise revenue, so the number of licences proliferated and/or the price of licences soared (e.g. one-off fees and royalty payments). A wide variety of licence types (and fees) may appear to work for the government in terms of revenue collection, but it restricts convergence and distorts competition within the industry. In such circumstances industry costs soar and industry structure tends to become overly complicated and fragmented.

Recent developments

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition that complex licensing rules and excessive fees have dragged down the sector and threaten the entire digital economy. This is not just a matter of licensing fees diverting potential infrastructure investment; it is the imposition of a suboptimal and static market structure on an industry that is characterized by dynamism and economies of scale and scope. As a recent GSMA report (GSMA 2016, 8) concludes, “effective regulation requires a holistic approach that addresses the diversity of all the relevant platforms” and “should enable, not discourage, the realization of economies of scale and scope that represent real savings for consumers”.

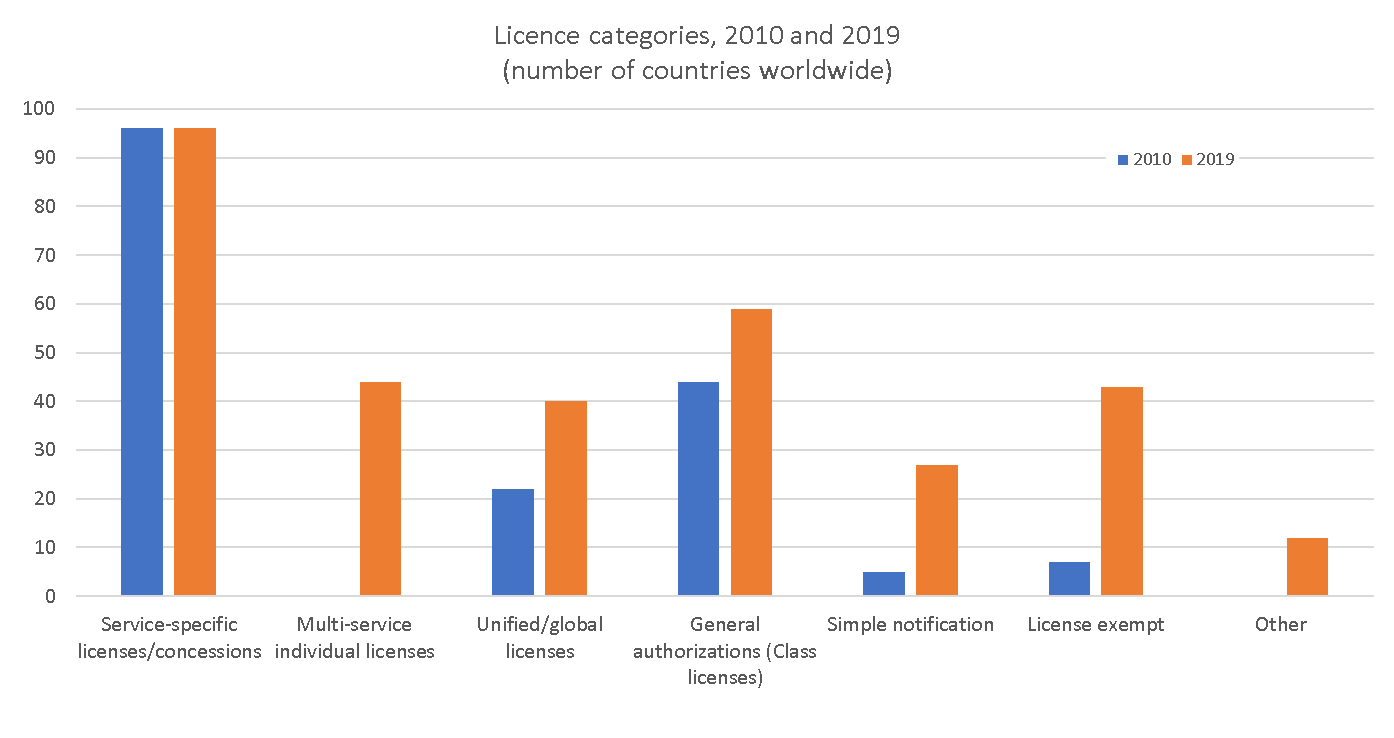

Such considerations have resulted in a trend towards open competition (where no licence is required) or general authorization (where a limited set of rules apply equally to all service providers within the class). As Figure 2.5 shows, most countries continue to have some service-specific licences, but they have greatly increased the number of multiservice and unified licences, and in some circumstances removed the need for licensing entirely with the creation of licence-exempt categories.[33] The other parallel trend is the simplification of the process of obtaining such an authorization (sometimes called a class licence) – often it involves little more than a simple registration procedure, without any licence fee. The ITU’s Global ICT Regulatory Outlook 2020 report (ITU 2020b, 26)[34] concludes that having a general authorization regime is one of the golden rules for unlocking the power of broadband.

But there are exceptions, especially for facilities-based licences. Convergence has driven the ICT sector towards a small number of network operators, with some countries and territories returning to a network monopoly to maximize economies of scale and scope and ensure national social and economic inclusion.[35]

Figure 2.5. The trend towards unified licences/general authorization

Source: ITU.

Key findings

- The objective of licensing is to ensure the effective, efficient delivery of ICT services.

- The optimal licensing structure and the terms and conditions of licences will vary by country; but the objective should never be revenue maximization.

- General authorization is to be preferred and fees should be negligible, set to cover administrative costs only, so as not to deter investment and innovation but also to enhance affordability for consumers.

- Where individual facilities-based licences are issued, the number of licences should be limited to avoid unnecessary duplication of investment, but they should be subject to conditions that provide for open access to key infrastructure on fair and reasonable terms[36] so as to create a healthy, competitive services market.

- Licensees should also be allowed to share infrastructure and to merge, subject only to competition policy considerations.

Mergers and acquisitions

Historical approach

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are an integral part of a properly functioning competitive market. Routes for existing players to exit the market gracefully are just as important as overcoming barriers to market entry.

M&A activity is only challenged by regulators if it would result in a substantial lessening of competition (SLC): typically, this may occur when an SMP supplier acquires a rival, or two smaller rivals merge to form a putative SMP supplier. However, the SLC test is speculative and difficult to apply because it involves assessing future market competitiveness under two future scenarios – with and without the merger – and then determining whether the difference is significant.

Good practice involves all mergers that pass certain threshold criteria being submitted for approval by the competent authority (e.g. national competition authority if it exists, working in collaboration with the ICT regulator). For example, in the United Kingdom, a merger usually qualifies for investigation by the Competitions and Markets Authority (CMA) if the business being taken over has a turnover in the United Kingdom of over GBP 70 million (about USD 86 million) or the combined business has greater than 25 per cent market share. Such threshold criteria are in place to avoid having to untangle a deal later – which is much more onerous process than simply preventing a merger or acquisition in the first place.

Recent developments

Mergers of licensed network operators have become commonplace as companies seek to achieve scale, provide universal coverage, and enable investment in 4G/5G and fibre networks. This gives rise to concerns about concentration, oligopolistic markets, and joint dominance.

Major digital platforms (such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon) have frequently acquired smaller rivals (such as YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram) in order to protect their market dominance.[37] The price paid is often excessive compared to market capitalization. Major platforms, Amazon in particular, is vertically integrating both forwards and backwards along the supply (or value) chain, so that it competes with suppliers and customers and exploits central dominance in new markets. Over time these activities have ossified digital markets, creating a “kill zone” around the big firms in which no new entrants can survive.

The SLC no longer functions well in determining whether regulators should intervene in M&A activity.[38] In general, the M&A activities of digital platform providers do easily pass the SLC test (they have only an incremental impact on the acquirer’s market share) but they nevertheless ensure that no embryonic company can ever gain the scale necessary to rival the network effects of the acquirer. New approaches are needed. In particular, such approaches need to look at market power not just in terms of revenues and subscribers, but also in terms of access to consumer data and the algorithms necessary to analyse and use that data, including potentially for anti-competitive purposes.

Key findings

- The legal framework should be modernized to give more scope for preventing and permitting M&A (as, for example, has recently occurred in Germany[39]).

- Resource the regulatory body appropriately, both in the number and the skills of staff, in order to address new types of M&A analysis.

- If M&A approval is subject to conditions, those conditions must be met before the merger or acquisition is undertaken.

- Enhance competition authority powers to move beyond fines (which are easily absorbed as the cost of doing business) and imposing a greater array of conditions (which are not easily ignored).

- Ensure that analysis of M&A involves multiple agencies across all affected economic sectors so that regulatory decision reflect the full impact of M&A on markets and consumers.

- The default outcome of a competition enquiry (triggered by relevant threshold criteria being met) should be to block M&A unless it can be proved to be in long-term consumer interests.

Taxation

Historical approach

Corporate taxes are designed so that all companies pay a fair contribution for the public services that they rely on (just as residents do through income and consumption taxes). Historically, corporate taxes have tended to be based on profit.

The tax burden on telecommunication companies, especially mobile network operators, is often much higher, especially in developing countries. Sector-specific taxes include excise taxes, higher-than-normal value-added tax (VAT), licence fees, spectrum fees, and universal service obligations. In a study of taxes in the mobile sector in 2017, the GSM Association found that mobile taxes on consumers and industry accounted for 22 per cent of market revenue and almost a third of these payments are in sector-specific taxes (GSMA 2019, 5). The full extent of ICT taxation is captured in Figure 2.6.

The rationale for these taxes is often that the mobile network operators are better at collecting revenue which is taxable than the government is at collecting taxes directly. This is probably true in many developing countries; however, it also has the unintended consequence of contributing to Internet access being unaffordable for many users across the world, and hence some of the economic and social benefits of the digital economy being lost. An ITU report (ITU 2015, 5) concluded taxation policy needs to be “based on country-specific policy trade-offs between revenue generation and the potential negative impact on the development of the digital sector as well as the telecommunication/ICT market environment”. However, as recently as 2019, the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development (2019, 63) reported that: “while greater recognition has been paid to the issues of affordability of ICT goods and services, and the role that taxation plays in improving affordability, in some cases, there have been notable increases in sector-specific taxes that have impacted adoption and use of connectivity services”.

Figure 2.6. Types of taxes applied to the ICT sector, world percentage, 2019

| Range of Taxes | |||||||||||

| Type of taxes | Content Services | Incoming int’l voice services | Int’l Data Services | Int’l Mobile Roaming | Internet Services | Nat. Data Services | Nat. Mobile Roaming | Nat. Voice Services | OTT Content Services | Outgoing Int’l Voice services (IDD) | Pre-paid mobile top-up cards |

| VAT | 0% – 27% | 0% – 27% | 0 % – 27% | 0% – 27% | 0% – 25% | 0% – 25% | 0% – 27% | 0% – 27% | 0% – 27% | 0% – 27% | 0% – 27% |

| Sector Specific | 0.1% – 17% | 0.1% – 15% | 0.1% – 13% | 0.1% – 49.77% | 0.1% – 40% | 0.1% – 40% | 0.1% – 26% | 0.1% – 49.77% | 1.5% – 13% | 0% – 40% | 0.1% – 49.77% |

| Sales | 3% – 35% | 0% – 27% | 1.5% – 27% | 4% – 27% | 3% – 35% | 1.5% – 35% | 3% – 27% | 1.5% – 35% | 5% – 25% | 3% – 27% | 3.65% -35% |

| Import Duties | 5% – 40.55% | 5% – 40.55% | 5% – 40.55% | 5% – 15% | 5% – 40.55% | 5% – 15% | 5% – 15% | 5% – 15% | 7.7% – 15% | 5% – 15% | 5% – 25% |

Note: Int’l refers to international and nat. to national.

Source: ITU.

Recent developments

Arguably, a mobile communications or Internet tax premium was justified when these were luxury services enjoyed only by the well-off. Taxes collected this way could be considered redistributive. But it makes little sense now that the emphasis is on achieving ubiquitous, affordable access.

As traffic and revenues move to OTT service providers and applications provided over digital platforms, taxes on traditional, usually mobile, services distort the market while broader ICT taxes and fees limit Internet affordability and deepen digital inequality. End-user surcharges for OTT services, such as have been adopted in several African countries, are self-defeating because taxing users tends to reduce the affordability of Internet access and suppress demand, which results in lower GDP and lower tax revenues overall.

Transnational digital platforms often pay much lower levels of tax than national firms – they use base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) practices that enable tax to be paid in low-tax jurisdictions rather than where economic activity occurs. Multilateral (e.g. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)) and unilateral (e.g. France, India) efforts are being made to establish fairer tax rules for digital platforms so that taxes are based on revenues generated in-country or based on profits proportional to the platform’s revenues in each country.[40] Other important features are simplicity and predictability.

As stated in the Global ICT Regulatory Outlook (ITU 2018b), taxation of the digital economy is a challenge faced globally and various approaches are being established. Governments should collaborate closely on digital services taxation matters at regional and international level, and should not compromise long-term, national economic benefits by targeting short-term revenue. In addition, it is relevant to establish effective mechanisms for collaborative regulation, given that taxation decisions fall to finance ministries and tax authorities rather that ICT authorities, for example, working together with all parties before making decisions.

Key findings

- Taxation of digital platforms and services based on their revenues (rather than profits) makes economic sense because of substantial network externality effects and because revenues are not subject to internal transfer pricing policies.

- Tax levels should not be such as to render universal access to digital services unaffordable: revenue-based taxes should be mitigated where, for instance, the service provider invests in the country (e.g. deploying infrastructure, covering rural and isolated areas, and creating jobs).

- At national level, governments should promote policies that (ITU 2018b):

- encourage balanced and harmonized taxes;

- avoid excessive burden to all stakeholders;

- promote both innovation and effective competition among all sector players in the digital ecosystem; and,

- consider affordability as a priority.

Endnotes

- ICT regulators or their counterparts elsewhere in government (e.g. ministries or competition authorities) ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The specific competition and regulation challenges of microstates”. ↑

- See Chapter 4 on “Consumer affairs”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Explanation of externalities on digital platforms”. ↑

- See Chapter 4 on “Consumer affairs” and Chapter 5 on “Data protection and trust”. ↑

- See EU 2015, 8 (Article 3). ↑

- See Rogerson, Holmes, and Seixas 2016, 9. ↑

- See the ITU website available here. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “ACCC review of digital platform regulation”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “OTT regulation in India”. ↑

- For a full description see Blackman and Srivastava 2011, 32ff; and ITU 2016. ↑

- For a full description see Blackman and Srivastava 2011, 38ff. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Market analysis in Moldova”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Approach to market definition in a digital platform environment. ↑

- For a full description see Blackman and Srivastava 2011, 119ff. ↑

- The historical development of interconnection rates in the European Union is described in Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The decline and fall of mobile termination rates in Europe”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “How the growth in data affects interconnection charges”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Red Compartida”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “European Electronic Communications Code”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “The decline and fall of mobile termination rates in Europe”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “A single integrated wholesale broadband network in Brunei”. ↑

- Adapted from ITU 2018b, 59, based on guidelines prepared by the ITU for the Communications Regulators’ Association of Southern Africa (CRASA) in 2016. ↑

- See, for example, Digicel 2019. ↑

- For a full description see Blackman and Srivastava 2011, 150ff. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Price approval and notification procedures in Iran”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “How to regulate price bundles”. ↑

- The UN Broadband Commission’s “1 for 2” target is 1GB at less than 2 per cent of monthly gross national income per capita (see Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development 2019, 34). ↑

- For disputes between operators (or service providers) and end users, see Chapter 4 on “Consumer affairs”. ↑

- For a full description see Blackman and Srivastava 2011, 147ff, and Bruce and others 2004. ↑

- There will always be an opportunity to appeal to the courts on matters of law and on whether the tribunal failed to properly determine its own jurisdiction. ↑

- The case is detailed in Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Court overturns Dutch regulator’s decision on joint dominance”. ↑

- For a full description of licensing and authorization, see Blackman and Srivastava 2011, 63ff. For a discussion of licence categories and types of licence, see Chapter 1 on “Regulatory governance and independence”. ↑

- In 2019, in addition to the figures shown in Figure 2.5, 116 countries report having a licence-exempt regime for wireless broadband devices. ↑

- Other golden rules include open competition in services and international gateways, infrastructure sharing, SMP-based regulation and foreign participation/ownership. ↑

- For example, see the Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “A single integrated wholesale broadband network in Brunei”. ↑

- See, for example, Digital Regulation Platform thematic sections on “Red Compartida, Mexico” and “A single integrated wholesale broadband network in Brunei”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “M&A activity of the main digital platform providers”. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Vodafone/TPG operational merger – SLC test no longer works well” for a recent case study. ↑

- See Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Germany adjusts its approach to M&A regulation”. ↑

- These trends are explored further in Digital Regulation Platform thematic section on “Unilateral and bilateral approaches to resolving BEPS”. ↑

References

A4AI (Alliance for Affordable Internet). 2018. 2018 Affordability Report. Washington, DC: A4AI. https://a4ai.org/affordability-report/report/2018/#executive_summary.

BEREC (Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications). 2016. Guidelines on the Implementation by National Regulators of European Net Neutrality Rules. Brussels: BEREC. https://berec.europa.eu/eng/document_register/subject_matter/berec/regulatory_best_practices/guidelines/6160-berec-guidelines-on-the-implementation-by-national-regulators-of-european-net-neutrality-rules

Blackman, Colin and Lara Srivastava, eds. 2011. Telecommunications Regulation Handbook: Tenth Anniversary Edition. Washington, DC: World Bank and Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. https://www.itu.int/pub/D-PREF-TRH.1-2011.

Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development. 2019. State of Broadband Report 2019. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/pol/S-POL-BROADBAND.20-2019-PDF-E.pdf.

Bruce, Robert R., Rory Macmillan, Timothy St. J. Ellam, Hank Intven, and Theresa Miedema. 2004. Dispute Resolution in the Telecommunications Sector. Discussion Paper. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and Washington, DC: World Bank. https://www.itu.int/ITU-D/treg/publications/ITU_WB_Dispute_Res-E.pdf.

Cave, Martin. 2006. “Encouraging Infrastructure Competition via the Ladder of Investment”. Telecommunications Policy 30 (3-4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2005.09.001.

Digicel. 2019. “OTTs and Network Infrastructure”. A contribution to ITU-D Study Groups, Question 3/1 and Question 4/1 joint session on the Economic Impact of OTTs on National Telecommunication/ICT Markets, October 2019. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/oth/07/1a/D071A0000030001PDFE.pdf.

EU (European Union). 2015. Regulation 2015/2120 of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down measures concerning open internet access, 25 November 2015. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015R2120&from=en.

FCC (Federal Communications Commission). 2015. Open Internet Order 15-24. https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-releases-open-internet-order.

FCC (Federal Communications Commission). 2018. Restoring Internet Freedom Order. https://www.fcc.gov/restoring-internet-freedom.

GSMA. 2019. Rethinking taxation to improve connectivity. London: GSM Association. https://www.gsma.com/publicpolicy/resources/rethinking-mobile-taxation-to-improve-connectivity.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2015. The Impact of Taxation on the Digital Economy. GSR15 Discussion Paper. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Conferences/GSR/Documents/GSR2015/Discussion_papers_and_Presentations/GSR16_Discussion-Paper_Taxation_Latest_web.pdf.

ITU (International Telecommunications Union). 2016. Principles for Market Definition and Identification of Operators with Significant Market Power. ITU-T Recommendation D.261, October. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-D.261-201610-I/en.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2018a. “Competition Analysis in Digital Application Environment”, Session 11, Regulating Two-sided Markets”. ITU Asia-Pacific Centre of Excellence, September 2018.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2018b. Global ICT Regulatory Outlook 2018. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Regulatory-Market/Pages/Outlook/2018.aspx.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2018c. GSR -18 Best Practice Guidelines on New Regulatory Frontiers to Achieve Digital Transformation. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/net4/ITU-D/CDS/GSR/2018/documents/Guidelines/GSR-18_BPG_Final-E.PDF.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2019a. ICT Infrastructure Business Planning Toolkit. Geneva: ITU. http://handle.itu.int/11.1002/pub/813e6d7f-en.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2019b. “Costing and Pricing Methodologies in the Digital Economy”. ITU, Regional Economic Dialogue on Information and Communications Technologies in Europe and CIS, Odessa, October 2019.

ITU, 2020a. Economic Impact of OTTs on National Telecommunication/ICT Markets. ITU-D Study Group 1 report, February. Geneva: ITU.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2020b. Global ICT Regulatory Outlook 2020: Pointing the Way Forward to Collaborative Regulation. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/pub/D-PREF-BB.REG_OUT01.

QMUL (Queen Mary University of London). 2016. Pre-empting and Resolving Technology, Media and Telecoms Disputes. International Dispute Resolution Survey. London: Queen Mary University of London. http://www.arbitration.qmul.ac.uk/media/arbitration/docs/Fixing_Tech_report_online_singles.pdf.

Rogerson, David, Pedro Seixas and Jim Holmes, Net Neutrality, Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, November 2016. https://telsoc.org/journal/ajtde-v4-n4/a79.

WTO (World Trade Organisation). 1996. Telecommunications Services: Reference Paper. Negotiating Group on Basic Telecommunications, World Trade Organization, April 24, 1996, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/telecom_e/tel23_e.htm.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022