National digital transformation strategy – mapping the digital journey

06.07.2023Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated digital transformation across the globe. The lockdown situation pushed much of the world online, and the use of digital technologies became indispensable to guarantee the continuity of public, private, and social life. This acceleration has amplified processes that have been under way for decades, resulting in the pervasive impact of digital technologies on many domains: from the individual level (engaging in online learning, working, and shopping) to entire nations (shifting towards digital economies, governance, society), from companies (chasing new business models, new services, new ways to deliver) to entire industries (moving to process automation, exploring benefits of artificial intelligence), from local authorities to national governments (offering more transparent and efficient governance, digital public services).

While digital transformation is a global trend and the world becomes increasingly digital (some estimate that 70 per cent of the new economic value globally will be created on digitally-enabled platforms over the next decade[1] and the global digital transformation market is expected to grow more than twice by 2025[2]), not everyone is affected in the same way. Digital transformation is not happening at the same pace and level of intensity in all countries: some countries are advancing more rapidly, while others are still in the early stages of adoption. The scope of digital transformation efforts varies from country to country, depending on factors such as economic, political and social context, as well as the level of digital connectivity, skills, regulatory maturity or others. Yet in 2022, 2.7 billion people remain offline. Universal and meaningful connectivity remains a distant prospect for least developed countries (LDCs), where only 36 per cent of the population used the Internet in 2022, compared with 66 per cent globally.[3]

Realizing the opportunities of digital and the risks of being left behind in the digital transformation race, governments worldwide are increasingly putting digital transformation at the front and centre of their policy agendas to drive social development and economic prosperity. According to the latest ITU data, half of all countries worldwide[4] have adopted digital strategies covering multiple economic sectors. The development of digital policy, legal and governance frameworks across and within regions is, however, markedly uneven. Only nine countries – fewer than 5 per cent of countries worldwide – are currently equipped with mature national frameworks for digital markets geared at transformational development of digital economies and societies.[5] Additionally, 30 per cent of countries globally have made progress in establishing advanced national digital policy, legal and governance frameworks. As a result, four distinct groups of countries can be identified, each at a different stage of digital development, and with varying levels of maturity in their national digital transformation strategies: countries with limited readiness, transitioning, advanced and leading countries.

The purpose of this article is to provide guidance to policy-makers, regulators, and entities dealing with digital transformation. It outlines the necessary steps and essential elements to be considered when developing a national digital transformation strategy by examining what needs to be achieved, why it is important, and how to do it.

Importance of having a national digital transformation strategy

Digital transformation offers huge potential. Econometric evidence suggests that digital transformation has positive impacts on economic growth and market outcomes.[6] From a governance perspective, digital transformation holds the potential to enhance transparency and accountability, limit bureaucracy, corruption, tax avoidance, and facilitate citizens’ interaction with their governments. For a society, it holds a promise to improve the provision of health and education services, facilitate social inclusion and communication, and improve well-being. Finally, digital transformation may positively impact environmental sustainability by smarter waste management and handling, pollution prevention and control, and sustainable resource management.[7]

Nevertheless, digital transformation can also result in negative effects, like workforce disruption, cybersecurity and data privacy issues, marginalizing even more populations that are offline or digitally illiterate, as well as contributing to negative effects on environmental sustainability (e.g. increasing volumes of e-waste, energy consumption, mining and extraction of natural resources needed for hardware products). This means digital transformation will not automatically guarantee success or automatically bring expected results.

Furthermore, national digital transformation is a complex process involving multiple stakeholders and their interests, covering various domains such as health care, education, transportation, energy, environment, governance and others. It involves significant investment, the need to address complex ethical and legal issues, and demands continuous adaptation to remain relevant in the ever-changing digital landscape. Navigating through the process is likely to be challenging, requiring the use of appropriate tools, and comprehensive and coordinated approaches.

A well-defined national digital transformation strategy (DTS) can serve as a guide – providing a decision-making framework, helping to prioritize national objectives, and guiding resource allocation towards desired outcomes. It can also help navigate uncertainties, even during changing and challenging times, and strengthen stakeholder coordination and collaboration. Furthermore, it is widely recognized that digital transformation is essential for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development[8] and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). When used properly, digital tools and technologies can act as a catalyst for advancing implementation of the SDGs. Aligning national digital transformation strategies with the SDGs encourages countries to apply a more balanced approach towards digital transformation, i.e. looking at different dimensions of digital impact.

In developing a well-defined national DTS, the following characteristics should be considered:

- Coherent – aligned with related domestic and international strategies and/or policies;

- Comprehensive, holistic – covers multiple sectors;

- Inclusive, empowering and human-centered – aims at closing all digital gaps (regional, gender, age, social groups) and ensuring that everyone can benefit from digital technology;

- Collaborative – engages all relevant stakeholders, including different parts and levels of government, non-governmental stakeholders and civil society, and establishes shared vision and values;

- Data-driven and evidence-based – assesses key digital trends, evaluates existing digital baselines, and existing policies, identifies opportunities and challenges of this digital journey;

- Ambitious but feasible – provides a clear strategic vision;

- Measurable – specifies concrete expected results and outcomes;

- Agile – has thorough monitoring and evaluation.

Developing a national digital transformation strategy

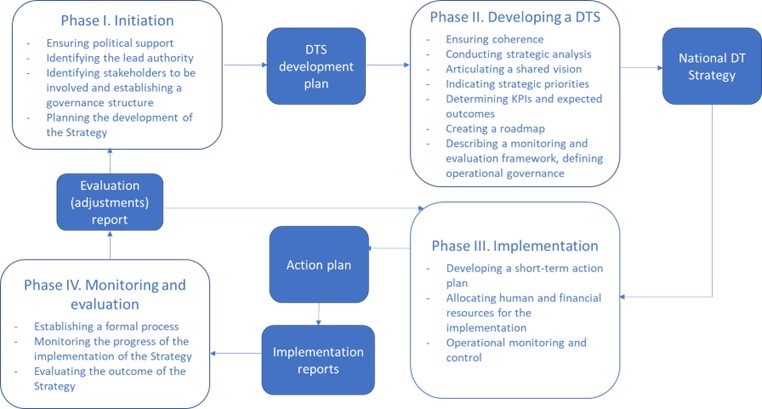

There is no unique universal strategic plan for digital transformation. It must be tailored to each country’s specific setting, including its political, social, and economic context, its leadership, culture, the overall complexity of the ecosystem, and other factors. A DTS will represent a unique mix of experiences, ideas, tools and available resources. However, the development of a DTS will always be a cycle, represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The cycle of DTS development

The following sections will review the four main phases of developing digital transformation strategies, putting emphasis on the most important elements in each phase.

Phase I. Preparation and initiation

The purpose of this phase is to develop an initial understanding among key decision-makers, leaders, and stakeholders about the importance of the overall strategic planning effort and main planning tasks. The purpose of this phase is to organize and guide efforts aimed at creating a national digital transformation strategy.

1.1. Ensure political will and political support at the highest level

Digital transformation is a journey that begins with firm commitment and a vision at the highest level. Political will[9] is crucial from the initial stages of a DTS formulation and is one of the essential prerequisites of DTS development and its implementation. It is needed to prioritize digital transformation on a national agenda, mobilize resources, and establish a clear vision for digital transformation. It is equally important for implementation of the strategy when political leaders demonstrate their commitment to the strategy by allocating the necessary resources, removing structural and organizational barriers, and promoting cultural changes.

Political support, on the other hand, refers to the broader political environment. It includes the level of public awareness and understanding of the issue, and the degree of consensus established among political parties and interest groups. When the benefits of digitalization are demonstrated as essential (a necessity) rather than optional (a luxury), it helps in shaping public narrative around digital transformation.

Therefore, the initial task for a government is to ensure political will and broader political support. This can be a challenging task – formal or informal engagement of political leaders might be beneficial, or sometimes, necessary. See Box 1.

| Box 1. Political will and support

An agreement between German political parties on national priorities was signed in 2021. The Coalition Agreement includes several provisions related to digital transformation, such as expanding digital infrastructure, increasing digitalization of public administrations and procedures, and promoting digital innovation, science and research. In 2021, four political parties in the Netherlands formed a coalition and signed an agreement, addressing national priorities, including several commitments related to digital transformation, such as investing in digital infrastructure and innovation, fostering digital skills and education, promoting the ethical use of data and digital technologies, working towards a safe and reliable digital environment. There has also been strong political support for digital transformation in Saudi Arabia. The Crown Prince and Prime Minister, Mohammed bin Salman, has been a vocal advocate for digital transformation and has emphasized its importance in the country’s Vision 2030, which aims to diversify the Saudi economy and reduce its dependence on oil. Source: Mehr Fortschritt wagen – Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit (spd.de), Coalition agreement ‘Looking out for each other, looking ahead to the future’ | Publication | Government.nl, Saudi Arabia Excels Digitally and Achieves Third Place in the world and Classifies as “Very Advanced” Country Among (198) Countries | Digital Government Authority (dga.gov.sa) |

1.2. Establish strategic governance that supports effective collaboration

A well-designed strategic governance framework that ensures intra-governmental and inter-sectoral coordination and collaboration – and establishes clear processes, roles and responsibilities of all involved parties – is fundamental for the successful formulation of a national DTS.

For the purpose of this article, strategic governance refers to a governance framework specifically designed to coordinate the processes of DTS drafting/formulation. Operational governance refers to a governance framework, focusing on the implementation of a national DTS.

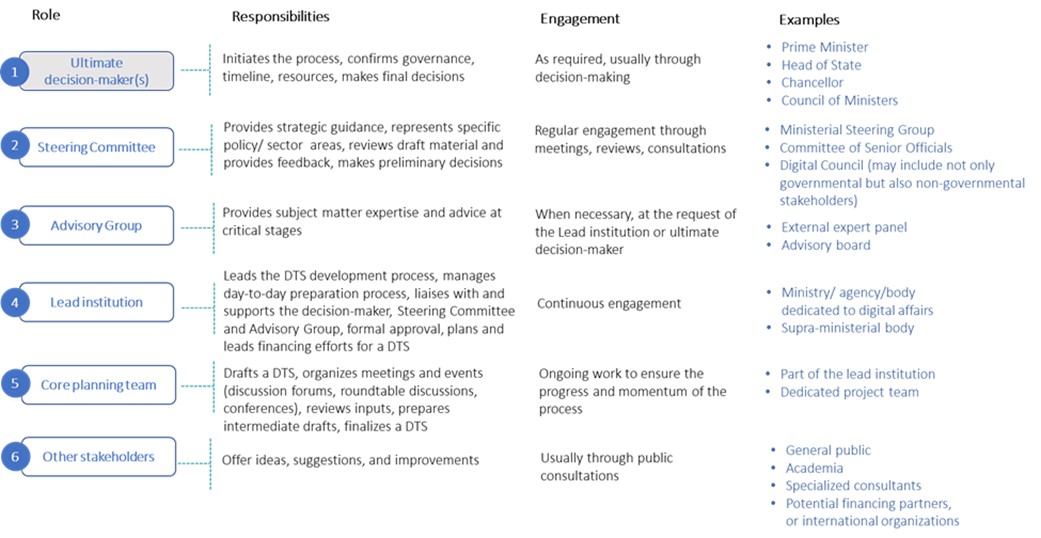

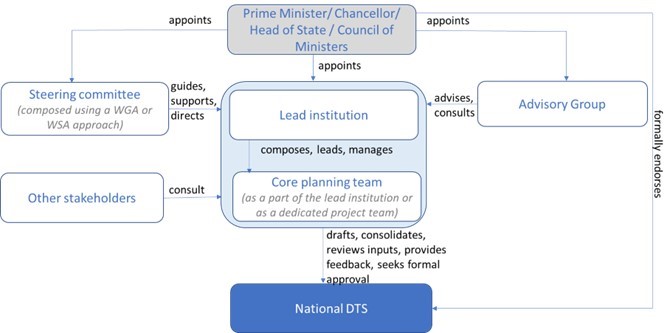

There is no universal (or one-size-fits-all) approach. While each country has its own specificities, it is important, however, to identify the main governance bodies and their roles and responsibilities in the process of DTS preparation. Different roles result in different degrees of engagement. Figure 2 lists potential governance roles and responsibilities, while Figure 3 is an illustrative example of possible interactions between different stakeholders.

Figure 2. Strategic governance roles and responsibilities

|

Figure 3. Example governance structure and possible interactions between stakeholders

1.2.1. Select the leading institution or body – identify the digital strategy lead

The development of a national DTS should be led by a competent authority with the political support, legitimacy and the mandate needed to lead and coordinate a comprehensive DTS.[10] The authority should have adequate financial resources and human capabilities to drive the DTS development process. Strong leadership ensures that DTS formulation is coordinated and integrated across multiple sectors and is properly prioritized in political agendas. Throughout changing political cycles, it ensures that national strategic directions, including digital transformation, remain stable.

Good practice also suggests that the lead institution should be neutral throughout the development process to overcome any inherent bias and avoid intra-governmental competition for resources. Therefore, it is recommended that this body (or a division of a lead institution) would be different from the one(s) that will be responsible for the implementation of the DTS, while strategic monitoring and evaluation usually would fall under the responsibility of the lead institution (see section Phase IV).

International experience suggests[11] that an increasing number of countries are allocating the responsibility for developing their digital transformation strategies to a ministry or agency dedicated to digital affairs or to a supra-ministerial body (e.g. directly linked to the Chancellery, the Prime Minister’s Office or to the Head of State or the Presidency). See Box 2.

Box 2. Leading institutions in selected countries

Source: ITU research. |

The lead institution in turn may appoint a dedicated team responsible and accountable for drafting a DTS (the core planning/coordination team).

1.2.2. Identify main stakeholders, establish key governance bodies

To be properly grounded in the national context, a DTS requires bringing multiple stakeholders together, engaging in some form of collaborative governance to support, guide and advise the lead institution in the development of a DTS. The goal of such collaborative governance is to foster a sense of ownership, a collaborative culture, and partnership among stakeholders to achieve better outcomes.

Collaborative governance structures can range from informal networks to more formalized structures, such as task forces, advisory boards, or co-management arrangements. Practice shows that often countries form a steering (or coordination) committee and/ or an advisory group (or board). Advisory groups, such as industry or expert panels, typically do not have decision-making power. Conversely, a steering committee, in addition to its strategic guidance, support, coordination responsibilities, may be involved in decision-making (or at least has a right to take some preliminary/interim decisions). However, in setting the governance structure for DTS development, the first task is to identify the main stakeholders. In doing so two main approaches may be followed:

- The use of a whole-of-government approach (WGA) – to accelerate progress on the digital journey, drive digitalization of governmental services, and better coordinate the development and implementation of national digital transformation initiatives. WGA refers to the joint efforts of ministries, public administrations and public agencies in order to deliver a common DTS and/or its implementation.

- The use of a whole-of-society approach (WSA),[12] which extends the WGA approach by placing additional emphasis on the roles of the private sector, academia, civil society and political decision-makers.[13] The level of openness, transparency and inclusiveness of the strategy’s design and development will determine the level of collective willingness to support its effective implementation.[14]

If WGA is the chosen approach, all ministries – as well as the sector-specific regulators, responsible for different sectors/industries (e.g. ICT, finance, energy, transport regulators), authorities and agencies with digital core mandates, such as data protection, cybersecurity, spectrum, as well as competition authorities, consumer protection authorities – should be considered as the main group of stakeholders, to ensure the breadth and depth of collaborative governance. This list is non-exhaustive and depends on a country’s institutional set-up. In this case, additional consultations with other stakeholders are strongly recommended (in any suitable form, e.g. roundtable discussions, workshops, traditional public or online consultations). If WSA is the choice – in addition to governmental stakeholders, representatives of the private sector (both large industry groups and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)), academia (universities, research institutions), and civil society (various associations or some individuals, visionaries, philanthropists) should be directly involved, i.e. be represented in governance bodies. Public consultations to ensure broader engagement and general acceptance of the DTS are also highly recommended.

Additionally, some ad hoc consultative advisory groups may be considered to review draft documents. The government or the lead institution may seek advice and guidance from external reviewers, including academia, specialized consultants, potential financing partners, or international organizations.

International experience shows[15] that WGA is the dominant approach, usually accompanied by consultations (rather than direct participation) with non-governmental stakeholders. Nevertheless, the WSA approach is gaining traction. See Boxes 3 and 4 below for examples of these approaches.

| Box 3. WGA in Germany

All federal ministries and the Chancellor, coordinated by the Federal Ministry for Digital Affairs and Transport (BMDV), have joined forces to deliver the Digital Strategy (2022). Besides describing the aspirational state and expected outcomes in three main strategic pillars – 1) connected and digitally sovereign society; 2) innovative economy, work, science and research; and 3) digital government – the strategy also lays out 18 digital lighthouse projects with tangible and measurable objectives, as well as mandatory to-do lists for all areas. Each department of the Federal Government is responsible for at least one digital lighthouse project. The projects are expected to be implemented by 2025 and mark a significant milestone in Germany’s digital journey. Implementation of the Digital Strategy will be monitored by a joint committee, made up of all departments of the Federal Government. Source: Digitalstrategie Deutschland | Digitalstrategie Deutschland (digitalstrategie-deutschland.de) |

| Box 4. WSA in Denmark

In 2021, the Danish Government established the Danish Government Digitisation Partnership to make recommendations for a new national digital strategy. The partnership brought together 28 members from Danish businesses, research communities, civil society, and local government. The work of the Digitisation Partnership resulted in 46 specific recommendations across seven areas. The Digitisation Partnership pointed to specific actions that harness the opportunities of digital and can contribute to Danish economic growth and social well-being. It also addressed some of the most pressing challenges, like the green transition, or increasing international competition. Building on these recommendations, in May 2022 the Danish Government launched the National Digital Strategy. The strategy marks Denmark’s first digital strategy spanning both the public and private sectors. Historically, digital development in Denmark has been the result of strong collaboration as well as broad political and general support. Previous strategies for digital development have included initiatives such as mandatory digital communication with the public sector and the introduction of digital self-service solutions for almost all administrative public services. These initiatives are now an integrated part of everyday life in Denmark. Source: Denmark’s long-term vision for digital development (openaccessgovernment.org) |

1.3. Prepare a plan for DTS formulation

In the final step of the initiation phase, the lead institution should prepare a plan for developing the national DTS. It should identify main steps, timelines, and human and financial resource requirements. It should also specify how and when relevant stakeholders will be expected to participate in the development process to contribute input and feedback. Once the plan is prepared, it should be approved by a steering committee and/or a government (an ultimate decision-maker) in accordance with the determined governance processes.

In setting a plan, a country will need to decide on a consultation process appropriate to its needs, context, and budget. As in the case of any public consultation, it is important to ensure transparency, inclusiveness and responsiveness of the process. Countries may consider using a variety of methods (e.g. online surveys, focus groups, public hearings, other) to ensure a wide range of inputs and, most importantly, that feedback is taken into account. The entire document can be made available for consultations, or only selected elements of a DTS, for example, the vision or the draft strategic priorities and actions, and at different stages of development, to stimulate broader engagement. Different formats should be considered for stakeholder engagement including roundtable discussions, workshops and conferences. In Canada, the government not only conducted the public consultation of the digital strategy through website and other digital platforms, but also organized 30 roundtable discussions with Canadians across the country in four months. The leaders reached out to a broad cross-section of society representatives including business leaders, innovators and entrepreneurs, academia, women, youth, local administrations, and citizens.[16]

Phase I in a nutshell: Preparation and initiation

|

Phase II. Strategy formulation

2.1. Map the existing documents to ensure coherence

To ensure coherence, the development of a national DTS should consider existing strategies and policies relevant to digital transformation. This can be achieved in part by a thorough mapping of strategic documents. In addition, a new DTS may require changes in some existing national documents or necessitate the issuance of additional documents to support a new DTS and ensure coherence.

To ensure coherence of a DTS, it needs to be aligned with higher-level national (e.g. national development plan, county’s long-term vision) and supra-national strategies (e.g. EU’s Digital Decade programme,[17] Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa,[18] Arab Digital Economy Vision,[19] ASEAN Digital Masterplan 2025[20] and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development[21]). Importantly, the question of how a DTS helps in achieving overall national, regional and/or international development goals needs to be addressed. Box 5 presents a sample of regional goals for digital transformation.

| Box 5. Regional goals of digital transformation

The EU Digital Decade sets out digital ambitions for the next decade. The EU aims to empower its businesses and people in a human-centred, sustainable and more prosperous digital future.[22] The main goals can be summarized as follows:

The vision for the Arab Digital Economy[23] is to transform the Arab world into a digitally-enabled economy and advance the region towards a sustainable, inclusive and secure digital future to enable an innovative, empowered and integrated Arab community. The strategy establishes 20 objectives structured across five dimensions:

The Digital Agenda for Latin America and the Caribbean (the eLAC2024 Agenda)[24] sets out policy priorities and strategic actions to foster digital transformation at the regional level and contains 31 objectives organized into four pillars:

Source: Adapted from the EU Digital Decade, the Arab Digital Economy Vision, and the Digital Agenda for Latin America and the Caribbean. |

A DTS should also ensure consistency with existing (or forthcoming) national strategic documents on key areas to be covered by a DTS (such as R&D, skills, education, innovation and others) in order to avoid overlaps or conflicting approaches, and to identify possible synergies. Existing documents related to digital transformation (including, but not limited to, ICT strategies, broadband development plans, universal service policies, sectoral digitalization policies and strategies, e-government development plans, data management and cybersecurity-related policies, and others) need to be mapped to position the DTS within the overall legislative structure.

In Saudi Arabia, digital transformation is integrated into the overreaching strategy/blueprint of the country. In Australia and Germany, the DTS serves as an umbrella strategy that provides the overarching framework for digital policy in their country. Boxes 6 and 7 illustrate strategic document mapping processes in Saudi Arabia and Australia.

| Box 6. Mapping DT documents in Saudi Arabia

Digital transformation is one of the key pillars for realizing Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. There are a few strategic documents aimed at fostering national digital transformation.

Source: Adapted from Overview – Vision 2030, Smart Government Strategy in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (my.gov.sa) |

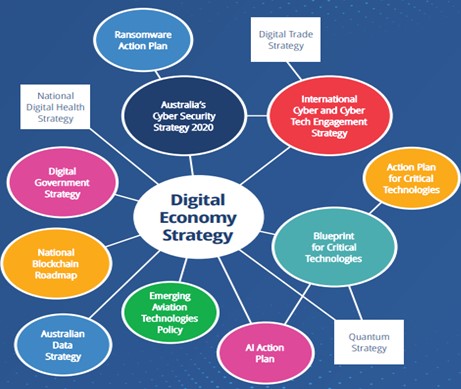

| Box 7. Mapping DT documents in Australia

Australia’s core overarching strategy for national digital transformation, the Digital Economy Strategy was launched in 2021 and updated in 2022. The Strategy sets the vision for the country to become a top 10 digital economy and society by 2030. The government takes a whole-of-government approach by bringing together policies and programmes across government to ensure a clear and coordinated path towards reaching the goal of being a top 10. Other strategic documents, such as the Cyber Security Strategy, Digital Government Strategy, AI Action Plan and others, are aligned with the Digital Economy Strategy.

Source: https://digitaleconomy.pmc.gov.au/2022-update/foreword |

Mapping existing strategic documents will also help to cross-check the strategic governance framework, i.e. which institutions shall take part in DTS preparation and its implementation, and whether existing institutional arrangements can adequately support the process or need to be augmented or adjusted. Document mapping will be one of the initial tasks for the leading institution and core planning team.

2.2. Conduct a strategic analysis – digital maturity and digital landscape evaluation

Carrying out a strategic analysis is the next step in the strategy formulation. Strategic analysis brings important information about the development of the digital ecosystem inside and outside the country and reveals possible opportunities and challenges that need to be considered in strategic decision-making.

The strategic analysis should encompass both – a digital landscape analysis and digital maturity assessment. A digital landscape analysis is more about analysing the external factors that can impact the national digital transformation process, and providing insights into opportunities and challenges. A digital maturity assessment focuses on evaluating the current state of the internal digital capabilities and readiness, helping to identify country’s strengths and weaknesses.

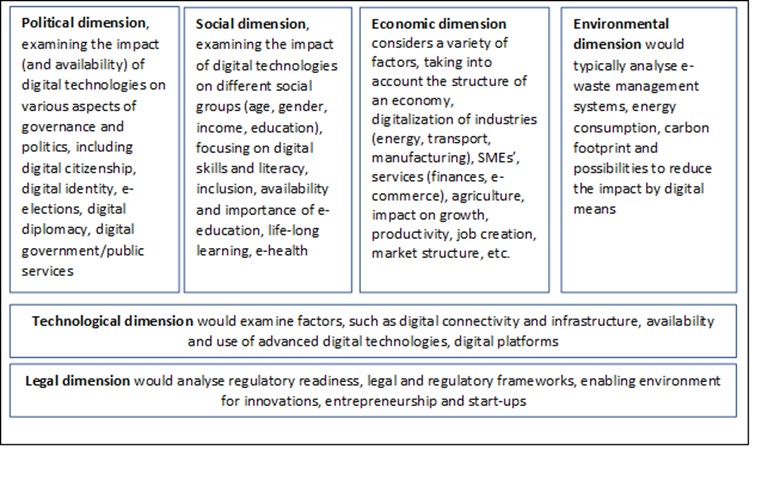

When conducting strategic analysis, it is important to adopt a well-rounded approach that considers multiple dimensions of digital impact, including political, economic, social, and environmental. PEST/PESTEL[25] tools are often applied (see Box 8). Additionally, gap analysis (identifying gaps between current and expected situations) and SWOT analysis (aiming at identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) are commonly used to identify strategic priorities and directions as well as possible quick wins to ensure digital acceleration. International benchmarking of selected indicators is also a widely adopted practice.

Box 8. PESTEL analysis

An international perspective can be valuable not only for the purpose of comparison but also for gaining insights into future developments. As part of their strategic analysis, countries may consider general regional and global digital transformation trends and their possible impact to a particular country, such as the rise of digital first policies, increased migration to cloud services, growth of big data hubs, accelerated adoption of artificial intelligence and machine learning capabilities, wider application of automation solutions, growing use of digital technologies and products with lower environmental footprint and higher energy and material efficiency. Box 9 provides a number of country approaches to strategic analysis.

| Box 9. Strategic analysis in Australia, the United Kingdom, Brazil and the Netherlands

Australia[26] conducted its strategic digital maturity analysis, first, by benchmarking the country’s achievements against selected countries. It also reviewed recent digital trends and how these are changing economic and social activities. Australia ranks well internationally on many aspects of digitalization, however, there are challenges still to be met, including increasing adoption of digital technologies across the economy, particularly by SMEs; maintaining and growing a skilled workforce; and stimulating greater development and adoption of digital technologies to meet Australia’s specific needs and others. Based on these conclusions, the country formulated its strategic vision for 2030. United Kingdom[27] also carried out an analysis/ review of its digital state of play in key areas – digital infrastructure, data-driven economy and its competitiveness, digital skills and talents, dynamics of digital innovations, start-ups and investments – and concluded, that the country is starting its digital journey with critical building blocks already in place and therefore aiming to maintain and strengthen its position in upcoming years. The Digital Transformation Strategy of Brazil[28] identifies five areas that are main enablers for its national digital transformation: i) infrastructure and access to ICTs; These enablers directly impact: 1) digital transformation of the economy (data-driven economy, connected devices, new business models), and 2) digital transformation of government (citizenship in the digital world and efficiency on provision of government services). In each of above-mentioned seven thematic axes the country conducted a diagnostic analysis, based on which it describes the aspirational state in each of them. The Dutch Government ordered a study “Foresight of Digital Economy 2030”[29] to analyse the most important trends and developments leading to 2030. The study provides an overview of the main opportunities and risks of digitalization. The new Dutch Digital Economy Strategy[30] (launched in 2022) sets the country’s strategic vision and strategic objectives based on the results of this study. It also considers the achievements of former digitalization strategies. Source: Digital Economy Strategy (apo.org.au), UK’s Digital Strategy – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk), Brazilian Strategy for Digital Transformation – Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (www.gov.br), Nederlandse Digitaliseringsstrategie | Nederland Digitaal |

Different instruments and frameworks to evaluate a country’s digital maturity and analyse the digital landscape have been developed by different organizations. The use of these is encouraged, while some adjustment may be beneficial. ITU’s G5 Benchmark,[31] the ICT Regulatory Tracker and the unified framework are unique tools that allow countries to assess the state of readiness of national policy; legal and governance frameworks for digital transformation may also serve as references in defining core regulatory readiness elements for the digital transformation. In addition, ITU developed the Digital Development Dashboard[32] that provides an overview of the state of digital development around the world and the Wheel of Digital Transformation, a conceptual framework geared to users, technologies and data and which provides a 6-step approach to digital transformation to assist countries on their digital journey.[33] Frameworks from other organizations are also available.[34]

2.3. Articulate a clear, ambitious, but feasible vision

The main purpose of a vision is to set out a broad direction, a course for future development. The vision therefore needs to be clear, meaningful and tangible. On one hand, a vision has to inspire, on the other hand, it also needs to be feasible. Therefore, it is important to find the right balance between achievable and ambitious when setting a vision. In general, a vision statement should consider these characteristics:

- Aspirational and ambitious. How the country will look in the future.

- Achievable. A vision should not be impossible. It should be challenging, but feasible.

- General. It should be broad enough to encompass all strategic objectives, like an umbrella.

- Meaningful. Sending a clear message to citizens, partners, and stakeholders.

The analysis of various DTSs reveals, that in setting their visions, less digitally mature countries tend to be more ambitious, whereas countries with a higher level of digital maturity mainly focus on maintaining or moderately advancing their current positions and improving their economic and social resilience. Box 10 provides examples of vision statements.

| Box 10. Vision (and mission) statements of selected countries

Netherlands –– the ambition is a resilient, entrepreneurial, innovative and sustainable Dutch digital economy, in which everyone in the country can participate. The government’s role is to ensure that everyone can benefit from the opportunities that digitization offers. Ireland – to be a digital leader at the heart of European and global digital developments. Kenya – improve Kenya’s and Africa’s ability to leapfrog economic growth. Viet Nam – to become a digital society by 2030, to overcome the status of a lower middle-income country by 2025, become an upper-middle-income country by 2030, and a high-income country by 2045. Republic of Korea – to become a best practice country in digital innovation and take a leap forward as a leading country in the digital era. Australia –to be a top 10 digital economy and society by 2030. Denmark – to be a digital frontrunner. Singapore – a digital-first Singapore is one where a Digital Government, Digital Economy and Digital Society harness technology to effect transformation in health, transport, urban living, government services and businesses (Smart Nation). |

2.4. Set clear priorities and strategic objectives

The strategic priorities (strategic pillars) grounded in the political, social, economic and environmental context are overarching objectives that will help to fulfil the vision (and the mission) in the long term. The strategic pillars, identified throughout a strategic analysis, hold up the vision. Remove a pillar, and the vision is at risk of collapse.

Practice shows that countries tend to focus on three to five strategic pillars when formulating their DTS. Some countries, like Singapore, Germany and Viet Nam identify three broad strategic pillars, such as the development of a digital government, digital economy and digital society. Other countries, like the Netherlands, Uruguay or Kenya, identify five, but more specific strategic pillars (see Box 11).

Box 11. Strategic pillars in Kenya’s, Uruguay’s and Dutch DTS

| The Kenya Digital Economy Blueprint | Uruguay’s Digital Agenda 2025 | Digital Economy Strategy of the Netherlands |

| The Blueprint establishes a five-pillar framework to realize a successful and sustainable digital economy in Kenya. The five pillars and underlying objectives include:

Digital government: improve government services to citizens and increase government revenue, productivity and cost reduction through digitized and streamlined processes. Digital business: adopt secure, affordable, open and efficient digital payment systems and financial services that protect consumers and encourage cross-border trade. Infrastructure: connect every Kenyan, business and government or public facility with broadband, as well as improve critical broadband infrastructure, such as the national fibre-optic backbone, undersea fibre cables and data centres. Innovation-driven entrepreneurship: increase the contribution of digital products and services to the Kenyan economy, and develop a sustainable support system for innovation through industry/academia research collaboration and access to funding. Digital skills and values: increase the number of graduates trained in advanced digital skills. |

Uruguay’s Digital Agenda 2025 is structured into the lowing five main priority areas:

Inclusive digital society: ensure digital citizenship and foster greater integration of all groups of the society by digital means. Boosting competitiveness and innovation in strategic sectors: create new employment strategies, simplify businesses interactions with public institutions, foster digital transformation in productive sectors through the incorporation of digital technologies throughout the whole value chain. Transparency, efficiency and governance of the public sector: efficiently employ data as an asset, digitally enhance public organizations, promote public innovations. Enhancing the ICT infrastructure, connectivity and cybersecurity at a national level: ensure global quality connectivity, increase cybersecurity, enable government as a platform for digital services and data. Regulatory framework enabling the national digital policy: ensure legal certainty and enabling environment for digital transformation. |

Dutch Digital Economy Strategy is also based on five strategic pillars:

Accelerating the digitalization of SMEs: with the objectives by 2030 to have i) at least 95% of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with a basic level of digitalization; and ii) at least 75% of SMEs using advanced digital technologies such as cloud, artificial intelligence and big data. Stimulating digital innovations and skills: with the aims to i) strengthen the country’s knowledge and innovation base in key digital technologies such as AI, blockchain, quantum, 5/6 G through public-private partnerships; and ii) have 1 million digitally skilled inhabitants by 2030 through the integration of digitization into education and requalification programmes. Creating the right regulatory and legal framework for well-functioning digital markets and services: through i) effective and dynamic regulation of digital markets; ii) ensuring fair competition in digital markets; and iii) legal protection of consumers in the digital environment. Maintaining and strengthening a secure, reliable and high-quality digital infrastructure: i) full connectivity to 1 Gbps broadband networks throughout the country, including 19 000 households currently in white spots; and ii) full coverage of 5G or equivalent technology in populated areas of the Netherlands. Strengthening cybersecurity: improving cyber resilience of businesses, determining cybersecurity requirements for digital products and services, and educating citizens. |

| Source: Kenya-Digital-Economy-2019.pdf (ict.go.ke) | Source: Uruguay Digital Agenda 2025 | Uruguay Digital (www.gub.uy) | Source: EZK Strategie Digitale Economie (brandam.nl) |

Each of the strategic priorities usually has its strategic objectives, i.e. steps that need to be taken to make progress in that specific strategic pillar. Ideally, each strategic objective contributes to at least one strategic pillar. When establishing objectives, it is advisable, when possible, to use the widely known SMART approach[35] – meaning that objectives have to be formulated in a Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound manner (see Box 12 as an illustrative example):

- Specific – target a specific area for improvement and focus on the change that is expected;

- Measurable – quantify or at least suggest an indicator of progress;

- Achievable – can realistically be achieved, given available resources;

- Relevant – focus on important areas, aligned with the strategic priority;

- Time-bound – specify when it can be achieved.

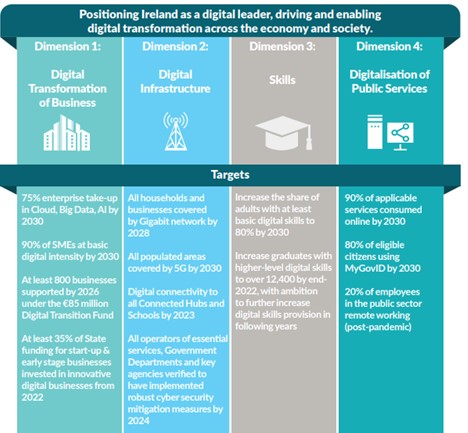

| Box 12. Digital Ireland Framework

The Digital Ireland Framework seeks to position Ireland as a digital leader, driving and enabling digital transformation across the economy and society. It is set out across four core dimensions, which are in line with the four cardinal points of the EU’s Digital Compass: Digital Transformation of Business; Digital Infrastructure; Skills; and Digitalisation of Public Services. Every dimension contains two to four clearly defined targets.

Source: gov.ie – Harnessing Digital – The Digital Ireland Framework (www.gov.ie) |

When designing a digital transformation strategy, it is important to focus on issues that have the greatest potential to unlock digital value and not overhaul everything at once. The first step is to identify those digital enablers – such as core digital infrastructure, cybersecurity, skills – that facilitate digital transformation across all economic and social areas. The second step is to identify and select a number of economic and social areas that will deliver the greatest economic and societal benefits from digitalization. It is important to establish clear prioritization so that resources are directed first to the most impactful and strategically important areas, while areas of a secondary focus will be addressed in later phases.

Box 13 below summarizes some of the most common enablers addressed in DTSs around the world.

Box 13. Key enablers of DT

|

Another approach to prioritize national strategic objectives is to set some guiding principles and values as criteria for guiding decisions and setting priorities. This approach was chosen by countries such as Denmark and Mexico. Both countries set five guiding principles that are being applied when choosing and prioritizing initiatives, activities, and work under their DTS (see Box 14 below).

| Box 14. Guiding principles

Denmark’s National Strategy for Digitalisation 1. Digital solutions must benefit everyone, drive growth and support competitiveness and productivity. 2. Digital development must focus on security, responsibility and ethics. 3. Digital progress must be made in collaboration between the public and private sectors. 4. Public data is a common good that must contribute to growth and innovation. 5. Denmark must shape digital development globally. Mexico’s National Digital Strategy 2021-2024: austerity (achieving high quality services with the maximum use of resources and reduction of expenses), fight against corruption, efficiency in digital processes, information security, and technological sovereignty. Source: National Strategy for Digitalisation (digst.dk), México tiene su Estrategia Digital Nacional 2021-2024 | Foro Jurídico (forojuridico.mx) |

A different approach in setting national priorities is applied by Switzerland. The Digital Switzerland Strategy 2023[44] is structured around five domains, which are aligned with the EU’s Digital Compass. These are long-term priorities; however, each year the Federal Council will set specific focus themes to make digital transformation efforts more targeted. Digitalization-friendly legislation, digitalization of the health-care system, and digital sovereignty are the focus themes set for 2023.

The prioritization of national digital transformation objectives should take into account the availability of financial resources, i.e. a country should consider the resources it currently has or will make available in the future for the implementation of the DTS. An estimate of required investments should be made and compared with available or planned resources. For example, the Danish Government is set to invest DKK 2 billion in the digital economy and society over the next five years.[45] The Republic of Korea plans to invest KRW 58.2 trillion, with the government’s spending of KRW 44.8 trillion by 2025 to implement its “Digital New Deal” strategy.[46] Prioritization helps to ensure that resources are directed towards the most important areas, and allows for a more focused approach to digital transformation efforts.

2.5. Determine strategic metrics (KPIs) and expected outcomes

Strategic objectives need to be measurable. It’s important to set key performance indicators (KPIs) to monitor progress over time. A DTS will require strategic long-term KPIs, whereas short-term implementation plans will demand operational KPIs. Strategic KPIs are more about monitoring progress or trends toward a stated destination, operational KPIs are about how planned tasks and activities are being performed. Ideally, strategic and operational KPIs will be aligned – connecting activities with overall achievements. At a minimum, strategic objectives should be (directly or indirectly) linked to the operational objectives. Both (strategic and operational) KPIs needs to be reviewed on a regular basis.

There are different types of KPIs to choose from: financial, outcome, qualitative, quantitative, leading, lagging and others. When choosing, it is important to:

- Define specific KPIs that align with the strategic objectives.

- Focus on a limited set of metrics that are most relevant to achieving these objectives.

- Ensure that the metrics are insightful and accurate data for the measurements is/will be available.

- Gain stakeholders’ acceptance of the metrics.

- Ensure that relevant data is collected regularly and establish who will be responsible for this task.

Strategic KPIs may be established for the whole strategy (e.g. Australia, see Box 15) and/or per strategic area or objectives (e.g. as in Germany and the Netherlands). Alternatively, or in addition, the outcomes expected at the end of a certain time-frame should be listed.

| Box 15. KPI Framework in Australia

Australia’s Digital Economy strategy defines six most important measures of success (strategic KPIs):

In addition to the key strategic KPIs, each objective in the strategy has its own expected outcome(s) by 2030, and some interim results (by 2025) are listed as well. This makes the strategy specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When defining strategic KPIs, it is also important to align them with internationally or regionally determined or recommended KPIs. This would ensure a proper strategic alignment, as discussed earlier. The EU Digital Decade Policy Programme, which sets the EU-level targets to be reached by 2030, covers connectivity, digital skills and digitalization of business and public authorities (see Box 16). In consultation with all stakeholders, the European Commission proposes[47] KPIs that would be key in monitoring progress towards the achievement of the digital targets laid down in the Programme. The results will feed into the annual State of the Digital Decade Report. When setting their national KPIs, many EU countries would refer to these commonly agreed KPIs. Some countries would stick to these strategic KPIs only, while others would use them in addition to their own.

| Box 16. Some suggested KPIs for the EU Digital Decade Policy Programme

The EC suggested a number of KPIs be used to measure the progress towards the EU digital targets, including: Digital skills, measured as the percentage of individuals aged between 16-74 with these skills; ICT specialists, measured as the number of individuals aged between 15-74 who are employed as ICT specialists; Gigabit connectivity, measured as the percentage of households covered by fixed very high capacity networks; 5G coverage, measured as the percentage of populated areas covered by at least one 5G network using the 3.4-3.8 GHz spectrum band; SMEs with at least a basic level of digital intensity, measured as the percentage of SMEs using at least four of 12 selected digital technologies; Cloud computing, measured as the percentage of enterprises using at least one of the determined cloud computing services;

Source: 2030 Digital Decade policy programme – key performance indicators (europa.eu) |

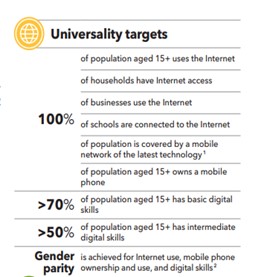

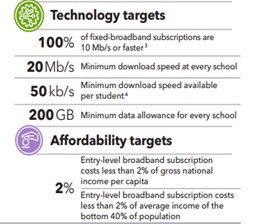

If regional KPIs are absent or do not fully support national strategic priorities, another option could be to align national strategic KPIs with internationally set targets and their metrics. For example, the 15 aspirational targets for universal and meaningful digital connectivity to be achieved by 2030, developed by ITU, the Office of the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology and their partners,[48] could serve as a basis in determining national connectivity KPIs (see Box 17).

| Box 17. Achieving universal and meaningful digital connectivity. Aspirational targets for 2030

|

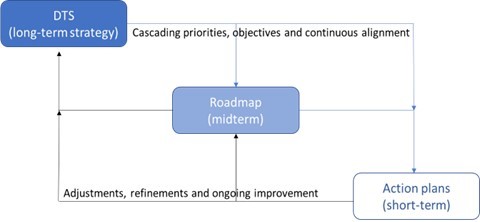

2.6. Create a roadmap

The purpose of a roadmap is to ensure that the strategy is translated into actionable steps. While the initial stage of a DTS focuses on defining the overall direction, vision, and long-term priorities and goals, a roadmap provides a detailed plan for achieving these objectives. Essentially, it breaks down the strategic objectives into more manageable and actionable tasks (see Boxes 18 and 19 for examples). It typically includes specific milestones, timelines, and tasks, initiatives with identified owners, time-frames and required resources. Since a DTS is usually focused on long-term goals, roadmaps are more likely to be mid-term oriented as they require more detailed information.

| Box 18. Actions, initiatives and milestones in Germany’s Digital Strategy

While formulating its Digital Strategy, Germany identified 24 action areas grouped into three strategic pillars (connected society, innovative economy, digital government). In each of the areas, the anticipated results, planned actions and interim expected outcome (by 2025) are listed. For example, in the area of Digital infrastructure, the objective by 2030 is “to provide nationwide, energy- and resource-efficient fibre-optic connections to the home and the latest mobile communications standard wherever people live, work and travel – also in rural areas”. Actions to reach it include:

The benchmarks for 2025:

In addition to such actions and expected outcomes in every of 24 action areas, Germany lists 18 so-called lighthouse projects, which the government aims to implement by 2025. Each ministry is responsible for at least one project. Projects aim at improving availability of mobility data, inclusive digital modelling of smart cities, improving applicability of digital identities, creating electronic patients records, national online training platforms, digital justice, digital donations, and others. Project implementation will be monitored on a regular basis by a council made from all ministries. Source: Digitalstrategie Deutschland (digitalstrategie-deutschland.de) |

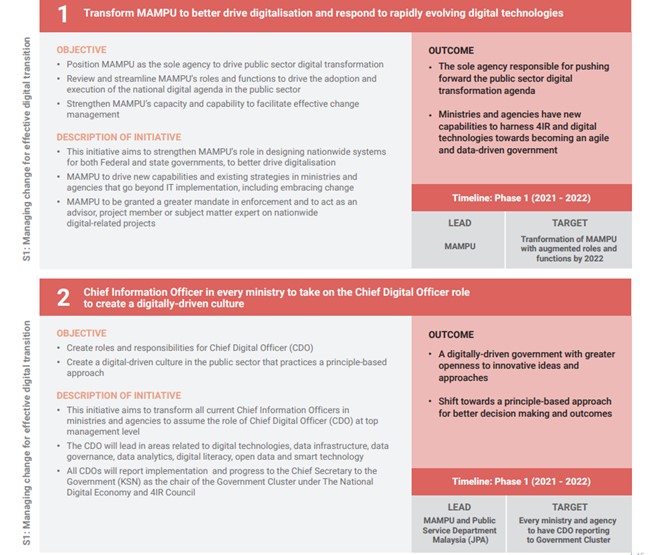

| Box 19. Extract from Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint – actions and initiatives

In 2021 after consulting various stakeholders, including governmental and non-governmental organizations, the Malaysian Government released the Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint. Known as “MyDIGITAL”, the Blueprint outlines efforts and initiatives to transform Malaysia into a digitally enabled and technology-driven high-income nation, and a regional leader in the digital economy. By 2030, the government aims to create 500 000 new jobs, achieve a 30 per cent uplift in productivity across all sectors, and have 875 000 SMEs adopted e-commerce, to have 100 per cent digitally literate public servants. To achieve these milestones, Malaysia has set up the “Digital Economy and Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) Council”, chaired by the Prime Minister, to lead at the highest level the development of the Blueprint, its implementation and monitoring. The Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit (MAMPU) also has an important role to play. It is a governmental agency tasked to lead the acceleration of the digital transformation of Malaysia’s public sector (one of the six core priorities of the Blueprint).

|

2.7. Ensure strategic monitoring and evaluation, define operational governance

As digital transformation is not a one-time exercise, but a continuous process, digital transformation planning is also about continuous monitoring, revision, adjustment and flexibility to adapt. Therefore, introducing an appropriate monitoring and evaluation framework – which sets guidelines on how, when and by whom DTS implementation will be monitored and reviewed – should be considered by governments. A well-designed DTS will have a defined monitoring and evaluation framework (see section Phase IV).

Good practice suggests that in order to smooth the transition from strategy planning to its implementation, it is beneficial to carry out the processes of drafting a strategy and defining a governance model for the strategy’s implementation in parallel.[49] Having a predefined operational governance model and explicit explanations or clear identification of the responsible entity for coordinating and overseeing the implementation of a DTS are valuable elements to include in the DTS document. This could be an institution with the responsibility to develop a DTS (e.g. Mexico, Brazil, Switzerland), a specialized cross-governmental committee (e.g. Ireland, Germany) or several designated bodies (the UAE). The implementation of individual tasks, objectives, or groups of objectives is usually scattered between different ministries or institutions according to their core mandate (see Box 20).

| Box 20. Coordination of DTS implementation

The implementation of Mexico’s National Digital Strategy is coordinated by the National Digital Strategy Office, housed in the Office of the President, however, implementation is carried out by various government agencies and private sector organizations. In Brazil, the Ministry of Economy Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication develops and coordinates the implementation of the Digital Transformation Strategy, while implementation of the strategy is executed by various ministries and agencies. The DTI Division of the Federal Chancellery in Switzerland is accountable for the ongoing development of the Digital Switzerland Strategy, while individual ministries, agencies and non-governmental bodies are responsible for implementing specific measures and reporting progress to the DTI Division on a regular basis. In Ireland, DTS implementation is driven via cross-government coordination structures, reporting to the Cabinet Committee on Economic Recovery and Investment. This includes regular engagement between the Senior Officials Group on Digital Issues and the Digital Regulators Group (consisting of the Commission for Communications Regulation (ComReg), the Data Protection Commission (DPC), the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (CCPC), and the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI). The development of the strategy is led by the Department of the Taoiseach. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Higher Committee for Government Digital Transformation was formed to supervise and guide strategic coordination of the development of the digital ecosystem for the UAE Government, where the coordination of implementation of the country’s Digital Government Strategy 2025 is in the hands of the Telecommunications and Digital Government Regulatory Authority (TDRA). The TDRA is responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Strategy across the country’s various sectors and ensuring that all stakeholders are working towards the common goal of achieving the digital transformation objectives. In addition, the UAE Digital Economy Strategy was approved by the UAE Cabinet in April 2022, and the Council for Digital Economy, chaired by the Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence, Digital Economy, and Teleworking Applications, was formed to overview the implementation. Source: Salud Digital | Gobierno de México presenta la Estrategia Digital Nacional 2021-2024, Transformação Digital — Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação (www.gov.br), Switzerland Strategy – Digital Switzerland Strategy 2023, gov.ie – Harnessing Digital – The Digital Ireland Framework (www.gov.ie), News (uaecabinet.ae), Digital economy – The Official Portal of the UAE Government |

| Phase II in a nutshell: Strategy formulation

• Map the existing documents to ensure coherence. The DTS should also ensure consistency with existing (or forthcoming) national strategic documents on key areas to be covered by the DTS in order to avoid overlaps or conflicting approaches, and to identify possible synergies. • Conduct a strategic analysis, including both a digital maturity and digital landscape evaluation to identify strengths and weaknesses. PEST/PESTEL tools can be used, as well as a gap analysis or SWOT analysis, or international benchmarking of selected indicators. ITU’s G5 Benchmark, ICT Regulatory Tracker, unified framework, the Digital Development Dashboard, and the Wheel of Digital Transformation can assist countries in their digital journey. Frameworks from other organizations are available as well. • Articulate a clear, ambitious, but feasible vision. A vision statement should be aspirational and ambitious; achievable; general; and meaningful. • Set clear priorities and strategic objectives grounded in the political, social, economic and environmental context. When establishing objectives, a SMART approach can help establish goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. • Determine strategic metrics (key performance indicators) and expected outcomes. There are different types of KPIs to choose from: financial, outcome, qualitative, quantitative, leading, lagging and others. Strategic KPIs should be aligned with internationally or regionally determined KPIs. • Create a roadmap to ensure that the strategy is translated into actionable steps. A roadmap can include specific milestones, timelines, and tasks, initiatives with identified owners, time-frames and required resources. • Ensure strategic monitoring and evaluation, and define operational governance. An appropriate monitoring and evaluation framework – which sets guidelines on how, when and by whom DTS implementation will be monitored and reviewed – should be considered. |

Phase III. Ensuring implementation – making the strategy implementable

The implementation phase holds fundamental importance within the overall lifecycle of a DTS. A systematic approach to implementation, backed by sufficient human and financial resources, plays a crucial role in ensuring the success of the strategy. The transition from planning phase to implementation phase is usually considered when the strategy is legally endorsed, and responsible bodies for strategy implementation are determined.

3.1. Translate strategy into operational reality: short-term plans

After the strategy is developed, it needs to be translated into a well-worked-out short-term implementation plan. If at the strategy level (especially in long-term strategies), the roadmap is more to indicate the milestones towards the aspirational situation, the short-term (usually on annual basis) implementation plans provide an effective basis for management control of implementation (see Figure 4). The short-term implementation plan translates strategic actions into sub-actions, implementable during this short-term planning period, and links them to departmental and individual goals. For example, Germany’s Digital Strategy was broken down into 134 tasks allocated to individual departments of the Government. The Netherlands prepares annual plans for its DTS implementation (see Box 21).

| Figure 4. Cascading principle of strategic documents

|

It is good practice to start preparing the accompanying action plan concurrently with the development of a DTS, as it eliminates time lags between the drafting of the strategy and developing corresponding actions for its implementation.

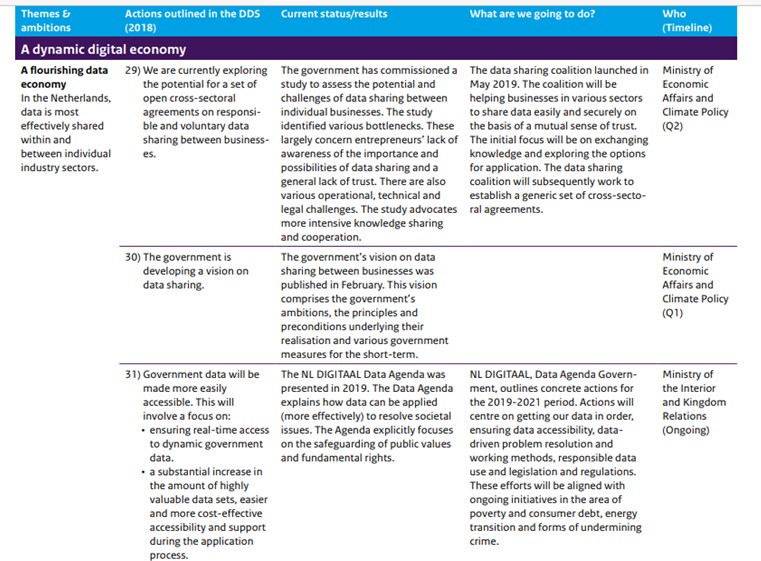

| Box 21. Extract from Dutch short-term plan

|

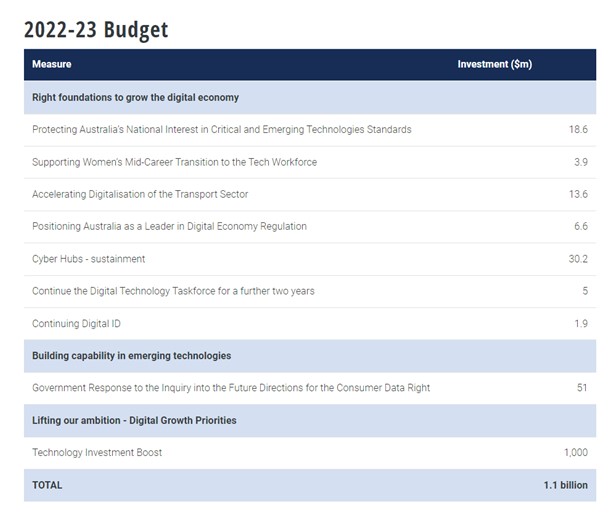

3.2. Ensure proper funding, secure commitments, create incentives

Appropriate resources (both financial and human) are the key to effective implementation. Implementation can only be driven forward when the budget is made available. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate, plan and allocate the financial resources necessary for strategy implementation. Some countries announce financial allocations for every funding period (i.e. annually, biannually, or through rolling budgets that cover multiple years, depending on the specific country’s practice). For example, Australia, specifies total investment for 2022-2023, as well as per strategic priority, and action line (see Box 22).[50] Other countries do not create a consolidated DTS budget, however, they make sure that institutions or bodies implementing one or another initiative or task of the DTS receive the proper funding.

| Box 22. Australia’s financial allocations to its Digital Economy Strategy

|

Usually, these budgets reflect the government’s financial commitments. However, the participation of other stakeholders, in particular, the private sector is critical. For example, the vast majority of connectivity investments, an estimated 75 per cent, will be from the private sector.[51] Therefore, governments also have an important role to play in bringing together all stakeholders to form impact-oriented partnerships for DTS implementation. A range of financial instruments and mechanisms exist – including state aid, venture capital, public-private co–financing mechanisms, and results-based financing – to mobilize and direct financial resources toward DTS implementation. Economic and fiscal incentives also have a crucial role to play.

Germany and the Netherlands are planning state aid mechanisms to cover their “white” broadband connectivity zones. In 2022, Australia introduced a few tax incentives for small businesses to smooth their transition into digital. By encouraging businesses with less than AUD 50 million annual revenue to invest in digital technologies, the initiative allows them to deduct an additional 20 per cent of the cost incurred on business expenses that support their digital adoption, such as portable payment devices, cybersecurity systems, or subscriptions to cloud-based services.[52] Small businesses also can benefit from an extra 20 per cent deduction for eligible expenditure on external training of employees.[53] In addition, the Australian Government recently introduced draft legislation to establish a Digital Games Tax Offset, to boost the growth of its digital games sector. A 30 per cent refundable tax offset will be available to eligible game developers that spend a minimum of AUD 500 000 on qualifying Australian development expenditure.[54]

Governments may consider not only financial or economic incentives, but also regulatory holidays, regulatory sandboxes, and other incentive-based, fair and transparent regulatory policies to foster stakeholders’ participation in digital transformation (as in Kenya’s case, see Box 23).

| Box 23. Regulatory incentives for mobile money in Kenya

When M-Pesa (mobile payment system) first emerged in Kenya, the Central Bank of Kenya took a hands-off approach to regulation.[55] Besides requiring users to register, the Central Bank of Kenya imposed few restrictions on the service. When combined with the rise of cheap mobile devices and a growing demand for financial services, this regulatory flexibility helped mobile payment apps spread rapidly across the country.[56] Today, almost 80 per cent of Kenyans use mobile money services.[57] Source: E-MONEY REGULATION (centralbank.go.ke), 9780821389911.pdf (worldbank.org) |

Financing resources as well as allocation mechanisms and schemes will differ significantly from country to country. It is clear, however, that mobilizing financial and knowledge resources from both public and private partners will remain critical for the successful implementation of digital plans. A coordinated and collaborative approach is needed – one that includes governments, businesses and development institutions working together in taking advantage of the benefits of digital.[58] As the ITU report “Financing universal access to digital technologies and services”[59] summarizes, pooling, collaboration and cooperation will be central to financing universal access to digital technologies and services and national digital transformations. The economic cost of exclusion is higher than the cost of closing the infrastructure, affordability, gender and other gaps that persist as the world becomes increasingly digitalized.

3.3. Train, educate, and build capacities

All digital transformation strategies acknowledge the significance of digital skills and education as a foundation for achieving strategic objectives. It is equally crucial for the government and public sector to possess adequate internal digital skills to effectively drive the national digital transformation process. Given the persistent shortage of digital talent worldwide, and the aging public sector workforce, governments need to take a proactive role in creating a pipeline of skills and competencies.[60] Digital Academies are being launched to keep up with this task (UK, Canada, Singapore, Saudi Arabia and many others, see also Box 24). They also play an important role in shaping digital culture in the public sector; such training, therefore, should extend beyond tech skills and foster the leadership and soft skills needed to support the culture change underpinning digital transformation.[61]

At the regional level, the Arab Federation for Digital Economy initiated the Arab Digital University as an integrated digital platform for education and vocational training that serves as a tool for spreading science and knowledge across emerging economies, covering the Middle East and North Africa, and West African countries.[62] At a global level, the ITU Academy provides access to training resources on a broad range of topics and is open to all who are interested in developing their capacities and skills in the field of ICT and digital developments.[63]

| Box 24. Building national digital capacities

The Ministry of Communications and Information Technology has announced the launch of the Saudi Digital Academy (SDA) as one of the key national initiatives aimed at developing the digital capabilities of Saudi youth in the field of modern and advanced technologies in partnership with the private sector, as well as applying best international experiences. The Danish Government Digital Academy was established to provide civil servants with the skills and tools necessary to manage in a public administration that is increasingly digital. Digital Lithuania Academy is an online learning platform that aims to guide the country’s public sector through the digital transformation. It seeks to immerse public servants in digital practices relevant to their work, and upgrade their professional profiles through a highly personalized learning pathway. By becoming increasingly tech-savvy, public servants have the chance to vastly increase their efficiency, find innovative ways of working, and deliver better public services to citizens. Source: MCIT and SAP Launch Training Program to Develop National Digital Capabilities | Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government Digital Academy (digst.dk), Digital Lithuania Academy – Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (oecd-opsi.org) |

3.4. Communicate

Once a DTS (and related documents, like action plans, budgets) is developed, it is essential to effectively communicate it. The purpose is to provide a clear understanding of the strategy’s purpose and significance. When all stakeholders comprehend the rationale behind, they are more likely to be supportive. Equally important is to ensure that stakeholders understand how the strategy is implemented. This necessitates making the progress of implementation transparent and visible.

Communication can be carried out through a wide range of communication means, such as official documents, websites, and publicity meetings. Two-way communication practices – such as roundtable discussions, conferences, and workshops – appear to be most effective, and provide an opportunity to get broader reactions and views on the strategy and its implementation. Extensive listening and feedback to comments received is a way of building stakeholders’ commitment to the strategy.

Visibility and effective communication not only help to transparently share values, purpose and progress, but also keep the spirit of collaboration and engagement. An increasing number of countries have dedicated websites and communication channels for their DTS, e.g. Switzerland,[64] Germany,[65] Australia.[66]

| Phase III in a nutshell: Ensuring implementation – making the strategy implementable

• Translate strategy into operational reality through short-term plans, which include adjustments, refinements and ongoing improvement to the DTS. • Ensure proper funding, secure commitments, and create incentives. A range of financial instruments and mechanisms exist – including state aid, venture capital, public-private co-financing mechanisms, and results-based financing – to mobilize and direct financial resources toward DTS implementation. Economic and fiscal incentives also have a crucial role to play. • Train, educate, and build capacities. All DTSs acknowledge the significance of digital skills and education as a foundation for achieving strategic objectives. Governments need to take a proactive role in creating a pipeline of skills and competencies. Digital academies are being launched to keep up with this task. • Communicate: provide a clear understanding of the strategy’s purpose and significance. Two-way communication practices (roundtable discussions, conferences, workshops, etc.) provide an opportunity to get broader reactions and views on the strategy and its implementation. |

Phase IV. Monitoring and evaluation

As stated in section 2.7, it is essential to establish a formal monitoring and evaluation framework. During the monitoring phase, the focus is on assessing if/to what extent the implementation of a DTS aligns with the initial plan. In the evaluation phase, the assessment of the strategy’s relevance shall be made and, if needed, the necessary adjustments determined.

As international experience reveals, monitoring and evaluation of government policies more generally lag behind in a vast majority of countries – in only one-third of countries ministries or regulatory agencies conduct ex-post policy reviews,[67] and still fewer, one in eight, conduct rolling policy reviews.[68] Without systematic application of basic policy review instruments, keeping implementation on track becomes a challenge, and accountability suffers, to the detriment of users, particularly those experiencing digital divides.[69]

In setting their monitoring and evaluation frameworks, countries have to clearly define: i) what indicators are being monitored, and how often; ii) who is responsible for data provision and accuracy; and iii) who is responsible for data consolidation and reporting. Equally important are establishing a clear schedule for evaluation activities; incorporating evaluation results into the planning cycle;[70] and clearly defining roles and responsibilities.

The institution with the responsibility of developing a DTS will usually be responsible for its strategic monitoring, evaluation and initiation of its update (see Box 25). To ensure deeper stakeholder engagement, some advisory bodies may be considered.

| Box 25. Reviews of national DTS

The Government of the Netherlands has updated its national digitalization strategy each year since 2018, when the initial Dutch Digitalization Strategy was launched. All updates review the results of the past year and reflect on new and upcoming trends. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy is set to drive the process. An overarching long-term digital strategy “Harnessing Digital – The Digital Ireland Framework” was published on 1 February 2022, the first progress report was already issued at the end of 2022, reporting on advancements in all strategic areas. The Department of the Taoiseach was leading the development of the strategy and is responsible for its monitoring and evaluation. Germany intends to analyse the impact of the Digital Strategy and present it to the public at the end of the legislative period in 2025.The Federal Ministry of Digital Affairs and Transport is to lead the process. The Federal Chancellery’s Digital Transformation and ICT Steering Division (DTI) is responsible for the ongoing development, coordination, communication and monitoring of the Digital Switzerland strategy. It reports annually to the Federal Council on the progress of the strategy and draws up proposals for new focus themes in close cooperation with the departments. The European Commission will prepare annual progress evaluations in the State of the Digital Decade Report to keep track of regional achievements towards EU strategic objectives, set in the EU Digital Decade. Source: About NL Digital | Nederland Digitaal, gov.ie – Harnessing Digital – The Digital Ireland Framework (www.gov.ie), Digitalstrategie Deutschland | Digitalstrategie Deutschland (digitalstrategie-deutschland.de), Switzerland Strategy – Digital Switzerland Strategy 2023, Europe’s Digital Decade: digital targets for 2030 (europa.eu) |

| Phase IV in a nutshell: Monitoring and evaluation

• Establish a formal monitoring and evaluation framework. Countries have to clearly define: i) what indicators are being monitored, and how often; ii) who is responsible for data provision and accuracy; and iii) who is responsible for data consolidation and reporting. • Establish a clear schedule for evaluation activities. • Incorporate evaluation results into the planning cycle. • Clearly define roles and responsibilities. |

Conclusion

While every country’s digital transformation journey is unique, it may be easier with a guide – a comprehensive DTS – the key elements of which are a clear strategic vision for the country’s digital transformation, clear priorities and objectives, measurable targets, sufficient financial and human resources, and a thorough monitoring and evaluation mechanism.

Digital transformation strategies may have different priorities, but in general they all aim to achieve They aim at digitalization of businesses, societies and governments. In addition, they all focuses on key enablers – infrastructure, skills and education, cybersecurity and trust, research and innovations, policy and regulations.

Alignment with sustainability plans is also gaining traction, with growing recognition of the interdependence of digital and green transformation. Digital solutions have a critical role to play in helping transition to a more sustainable economy and society. The green transformation can shape the future of digital technologies, with reduced resource usage, waste, and greenhouse gas emissions.[71] Sustainability is being gradually integrated in national DTSs as a cross-cutting component to harness digital transformation as a positive and exponential force for progressing environmentally and socially sustainable development.

Currently, four broad groups of countries can be identified, each in different stage of digital development, defining their transformation priorities accordingly.

- Limited readiness countries are currently in the primary stage of digital development, with limited digital initiatives or programmes, and have yet to plan their digital transformation.

- Transitioning countries that are focusing on strengthening their digital foundations: i) their digital infrastructures and connectivity; ii) digital skills to enable more people to contribute to and benefit from digital transformation; iii) enabling regulations and policies; and iv) digital government – as a catalyst for further digital development.

- Advanced countries focus more on consolidating digital technologies and industry know-how to accelerate digital transformation. They also aim at fully-fledged digital inclusion, advanced state of privacy, online safety and cybersecurity.

- Leading countries have reached the state of digital development, when they are testing and introducing new technologies everywhere, continuously learning, experimenting, innovating and progressively evolving into smart and sustainable nations.

The answer as to which digital strategies will succeed and which may fail is complex, but clues could be found in these elements: the strategy itself; governance and institutional framework; leadership, human and financial capacities; and commitments and strength of stakeholders’ partnership. Other elements include acceptance, in general, of key cultural changes – collaboration, experimentation and innovation, and continuous learning.

Digital transformation is driven on a tough road. It requires smart strategies, smart implementation, and the right (outcome-oriented, collaborative) mindset. While governments can act as stewards of digital transformation, all parts of society must collaborate for the greatest chance of success.[72].

Endnotes

- Shaping the Future of Digital Economy and New Value Creation > Platforms | World Economic Forum (weforum.org) ↑

- The World’s Digital Transformation Industry 2020-2025: (globenewswire.com) ↑

- ITU Facts and Figures: Focus on Least Developed Countries ↑

- A total of 94 countries have overarching, cross-sectoral digital policies or strategies, according to analysis based on the G5 Benchmark 2021. (Broadband plans and universal policies are not counted here.) ↑

- ITU Global Digital Regulatory Outlook, 2023 (GIRO). ↑