Monitoring and evaluation of universal and meaningful connectivity impact

01.09.2025Importance of monitoring and evaluating universal and meaningful connectivity policies and projects

A key consideration for the design and implementation of policies aimed at promoting access for all is ensuring ongoing monitoring and evaluation of whether a policy or individual project is meeting its intended goals. This consideration of accountability should be a foundational design component of universal and meaningful connectivity (UMC) and universal access (UA) approaches, and relies both on clear, measurable objectives and on the ability to measure progress against them. In a sense, this equates UMC and UA policies and plans with many other government policies or programmes, for which policy-makers need to design and implement mechanisms for monitoring effects. In addition to transparently disbursing funds in support of universal access service fund (UASF) targeted projects, it is also particularly important to evaluate whether such spending is an effective and efficient use of collected funds.

As such, two approaches to monitoring and evaluating the impact of UMC policies may be considered: (i) evaluation of the overall policy, and (ii) evaluation of individual UASF-supported projects. In both cases, the establishment of clear goals and/or milestones will lay the groundwork for later impact evaluation.

Evaluating UMC policy impacts

For UMC policies, governments should set specific, attainable goals for the key aspects of the policy. This could include, for example, ensuring Internet connectivity in a minimum number of locations or to a minimum percentage of the population, ensuring access to a certain level of connectivity without exceeding a certain proportion of per capita national income, and ensuring a minimum level of service quality. The inclusion of specific goals or milestones allows a review of the efforts undertaken as a result of the policy. For example, if a UMC policy includes a goal of increasing the percentage of the population with access to a 10 Mbps Internet connection to at least 98 per cent within five years, a subsequent review should be able to evaluate whether that goal was met. If resources permit, an interim or mid-term assessment of the policy’s impact is a particularly useful tool, allowing for course corrections before the target date is reached.

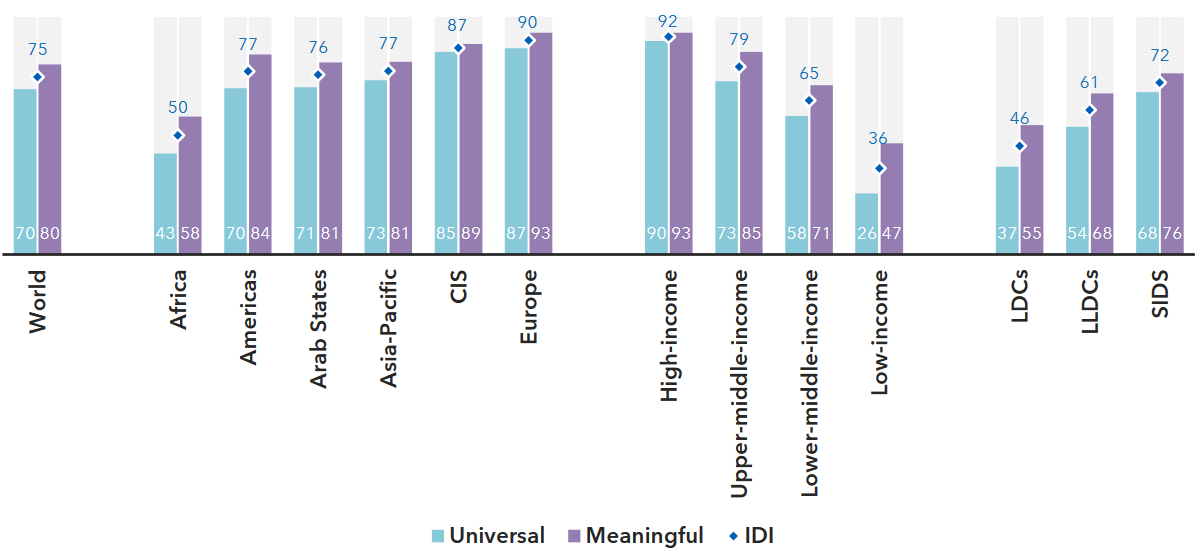

It is also instructive to consider the country’s progress toward achieving universal and meaningful connectivity. Beginning with the 2023 ICT Development Index (IDI), ITU adopted a new methodology that is based on the UMC concept. The IDI, published annually, assigns a universal connectivity score and a meaningful connectivity score to each country, as well as providing overviews by region and income, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Universal and meaningful connectivity pillar scores, by region and income group

Source: ITU 2024.

As noted in the 2024 IDI, the meaningful connectivity pillar is driven by infrastructure indicators, which depend heavily on operator deployment activities and strategies. The universal connectivity pillar, by contrast, depends more on consumer adoption and reflects a persistent usage gap. The IDI also notes that meaningful connectivity scores tend to be higher than universal connectivity scores across all regions, income groups, and development status, though the two scores converge as income increases.

Monitoring universal access funds and projects

A review of successful UASFs demonstrates that certain capacity requirements are necessary to attain UA goals. A UASF carries many of the same functions as a financial institution, including managing large capital assets, evaluating and defining projects for investment opportunities, and providing financing to implementing contractors, whose operations must be overseen and evaluated to ensure the UASF’s resources are well spent. UASFs can and should be evaluated with respect to their own structure and operation as well as with respect to the projects undertaken by the funds. Box 1 provides an overview of fund assessment factors considered in the Universal Service Financing Efficiency Toolkit.

Box 1. Assessing universal access funds

| Assessing universal access funds

The Universal Service Financing Efficiency Toolkit provides guidance on assessing the effectiveness of UASFs. This includes assessing the performance of the fund with regard to several factors:

More information can be found in the Assessing the Fund section of the toolkit. |

Source: ITU Universal Service Financing Efficiency Toolkit.

From a project perspective, UASF-funded projects should be designed to have specific implementation milestones and goals that must be met, and clear criteria against which success can be measured. Traditional voice service-focused UASF-supported projects have often been structured such that payment is disbursed upon successful, timely completion of project milestones, providing recipients with an incentive to meet the stated implementation timeline and goals. This approach is equally applicable to UASF-supported projects for expanding access to the Internet and digital services more broadly. Funding recipients should be able to substantiate that they have met goals that may include not only connectivity, but adoption, price levels, skills and training, variety of services available, or services available to disadvantaged populations.

In line with meeting specific milestones and timelines, UASF-funded projects should include reporting requirements that may incorporate a progress assessment, analysis of any unexpected circumstances, financial statements, and any other relevant analysis, particularly in cases of deviation from initial project plans. As above, such requirements may not markedly differ from reporting requirements for a telephony-focused project but should be tailored to the particular project and its goals. Thus, additional reporting requirements could include, for example, average available broadband speeds, access to particular digital services, or measures to ensure access for people with disabilities. The goals of reporting requirements should be to enable all stakeholders to assess project progress or success, and also to serve as a motivation for the funding recipient to commit appropriate resources to meet the project goals.

As an illustration, the rules governing India’s Universal Service Obligation Fund, Digital Bharat Nidhi (DBN), empower the organization to “monitor, evaluate or verify the work done by Implementers through any competent body including any third-party agencies” (Department of Telecommunication 2024). The predecessor universal service fund agency in India included multiple provisions in its funding agreements intended to guarantee adherence to the project terms and conditions. For example, a 2024 fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) pilot project agreement incorporated inspection, testing, and monitoring provisions empowering the agency or its representative to inspect the infrastructure and conduct performance tests and to conduct investigations to determine whether there has been any breach of the agreement terms (Universal Service Obligation Fund 2024, link to be added). The provider is also required to permit the agency or its representatives access to the network operations centre/network management system. The same agreement requires that subsidy claims must be audited by the provider’s appointed auditors.

Further, the same pilot project incorporates an incentive mechanism based on net addition of new FTTH connections (Universal Service Obligation Fund 2024,link to be added). The incentive relies upon verification of additional connections, serving as an additional mechanism by which project progress can be monitored.

In Kenya, the regulator’s draft universal service fund strategic plan for 2022-2026 details a monitoring and evaluation framework to track key performance indicators (KPIs) associated with milestones and deliverables. KPIs include metrics related to coverage, quality of service, device adoption, baseline coverage, the number of community networks established, and the number of new technologies leveraged to enhance coverage, among others. Further, the regulator established strategic objectives that outline high-level goals for the rollout of telecommunications infrastructure. The objectives and KPIs are used to formulate the fund’s budget and are assessed quarterly for compliance with planned implementation goals (Communications Authority of Kenya 2022). Chile’s universal service fund also incorporates provisions into project contracts that link subsidy disbursal to project completion, while also publishing information regarding the projects supported by the fund.

A further consideration with respect to project monitoring and evaluation is whether the responsibilities and obligations established by regulatory frameworks result in appropriate oversight activities. For example, a 2023 GSMA study of Sub-Saharan Africa indicates a wide discrepancy between regulatory authorities and service providers regarding the presence of a monitoring and evaluation mechanism for assessing the performance of funds disbursed from universal service funds (GSMA 2023). The survey found that while 78 per cent of surveyed authorities indicated the presence of a monitoring and evaluation system, only 11 per cent of service providers responded that such a system was in place. There may be varied reasons for the discrepancy, including reporting difficulties, inactive or inefficient UASF administration, or simply failure of one or both parties to follow through with reporting and review obligations.

UMC policy and project monitoring is a key policy element for increasing the likelihood of success. While the concept dates back to the earliest UA policy approaches, it can and should be applied to modern UMC and digital service needs.

Last updated on: 09.09.2025