Access for All: Value Creation and Demand

01.09.2025Introduction

The broadband ecosystem consists of two key components – supply and demand. On the demand side, value creation is essential to universal service initiatives. This aligns with the Broadband Commission’s observation that there has been a fundamental shift from supply-driven communications access to demand-driven communication (Broadband Commission 2023). While many communities and individuals around the world recognize the value and importance of connectivity, others may need additional support, such as incentives, education, or expanded opportunities to access online services. By understanding the dynamics that impact broadband demand and value creation, policymakers and other government stakeholders can create effective strategies to advance universal service goals and ensure that broadband benefits are experienced by all.

This article explores the critical role of these factors in universal service, and offers a series of examples and good practices to keep demand and value creation at the centre of effective policy measures.

Demand as a universal service driver

To achieve universal and meaningful connectivity (UMC) targets, policymakers need to consider the role of demand as a driver for achieving universal service. The Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development (Broadband Commission) defines meaningful connectivity as a level of service that allows users to have a “safe, satisfying, enriching and productive online experience at an affordable cost,” while universal connectivity means connectivity for all (Broadband Commission 2024a). Under this framework, this section will discuss several factors that lead to low broadband demand, as well as the impact of low demand on universal service goals and the role of anchor institutions in meeting these goals.

Factors leading to low demand

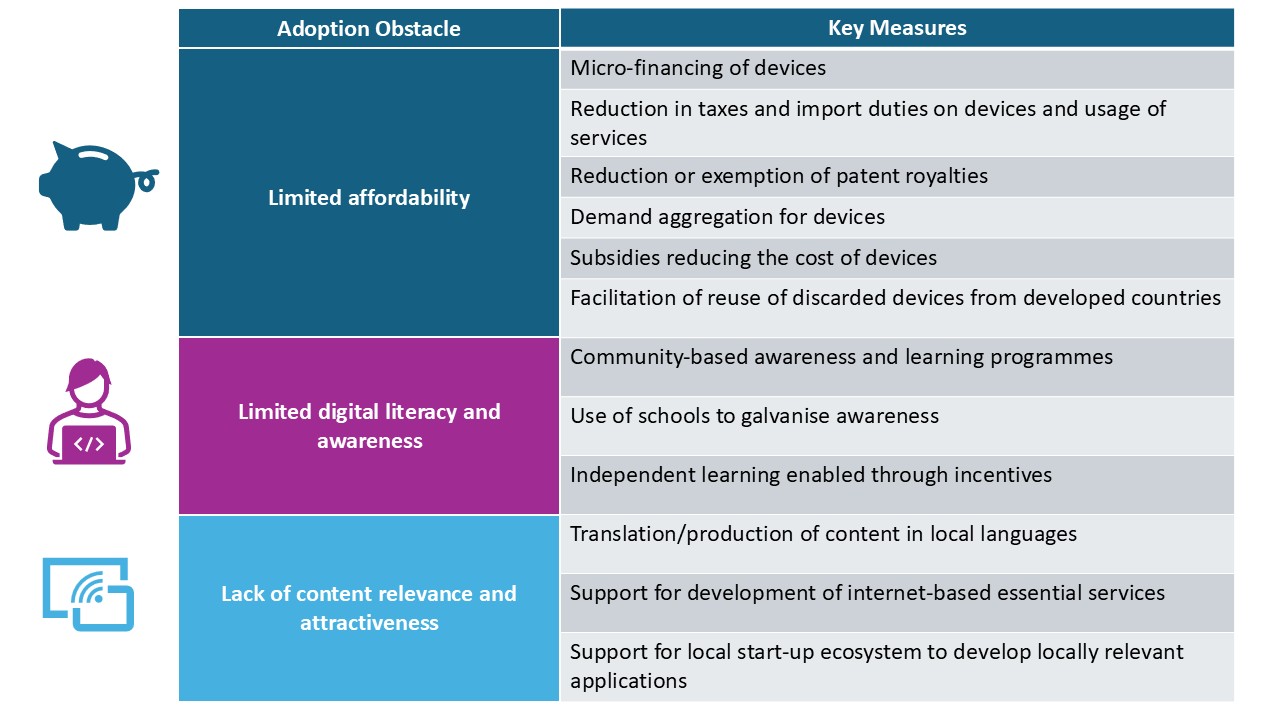

While many parts of the world lack high-speed, affordable broadband infrastructure, many individuals have access to broadband but do not use it – this is known as the adoption gap. Several factors lead to the adoption gap as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Primary adoption obstacles and key measures to overcome them

Source: Broadband Commission; TMG.

Source: Broadband Commission; TMG.

Limited broadband adoption is significantly influenced by the three key pillars identified in Figure 1: limited affordability, limited digital literacy and awareness, and lack of content relevance and awareness. While mobile broadband services have become more affordable in most regions, the cost of connectivity services continues to account for a disproportionate share of income. [the article on Access and Affordability]. According to ITU data, not knowing how to use the internet (i.e., digital literacy) is the second most-common reason that individuals with connectivity are not online. This is especially true for individuals over the age of 75 – in Canada, 78.6% of survey respondents over 75 listed not knowing how to use the internet as their top reason for not being online (ITU 2022). A comparatively low level of locally relevant content also decreases demand for broadband services – users will have less interest in content that is not relevant to their context or available in accessible languages. According to the internet Society Foundation, 82% of online content in 2023 was published in only 10 languages (Internet Society Foundation 2023). The comparative lack of content and applications in the nearly 7,000 other languages used around the world limit users’ ability to engage with educational, social media, e-commerce, and other online platforms, contributing to a lower level of demand for broadband service.

These challenges are disproportionately experienced by particular societal and economic demographic groups, including older adults, women (particularly in developing nations), and people living in rural areas (ITU 2021). In addition, factors such as cultural norms and concerns over privacy and security of online activity can also dampen interest in using or subscribing to broadband connectivity and online services (ITU 2022).

Impact of low demand on universal service goals

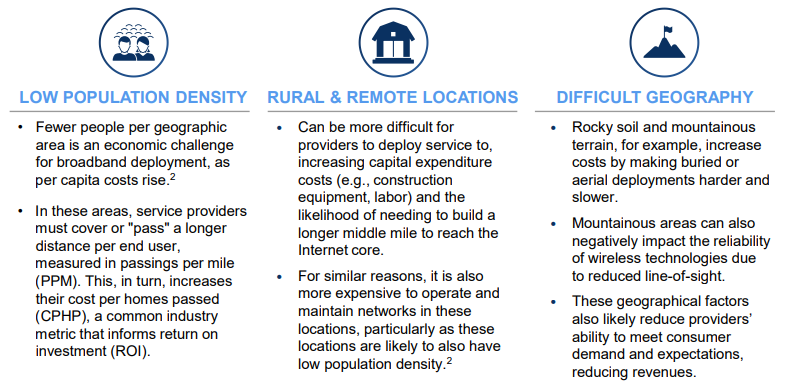

Low broadband demand is a limiting factor to policymakers’ ambitions of universal service, and it is important to consider how low demand influences issues related to access and affordability. First, low demand leads to higher infrastructure deployment and maintenance costs per subscriber for operators, which decreases revenues and weakens their overall business case (Broadband Commission 2021). This can perpetuate the digital divide, as operators choose to make investments in network infrastructure in areas that are deemed more economically viable – those areas in which a larger proportion of the population is likely to subscribe to broadband service. This is even more evident in areas with low population density, rural areas, and places with unique geography. These areas are disproportionately impacted by the adoption gap due in large part to lack of an attractive business case for privately-owned network and service providers, as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Characteristics of unserved and underserved areas

Source: National Telecommunications and Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce.

As shown in Figure 2, Providing service to remote or hard-to-reach areas faces significant capital investment challenges. These areas often have populations with lower broadband service demand levels due to factors such as income levels, digital literacy, or perceived need, creating a cycle where high infrastructure costs meet low market demand. It is therefore essential for policymakers to pursue measures that encourage individuals to adopt – and maintain – broadband connectivity, interrupting the high infrastructure cost-low demand cycle.

Role of anchor institutions

Globally, countries are increasingly recognizing the role of anchor institutions in fostering demand and creating value for broadband services. These institutions, which include primary and secondary schools, higher education institutions, libraries, community centres, government offices, and hospitals, provide connectivity to populations that use or work within such institutions. There are many documented benefits of providing service to anchor institutions, such as:

- stimulating economic growth;

- promoting individualized learning;

- reducing the cost of health care; and

- expanding community services (Benton Institute for Broadband and Society 2016).

Many anchor institutions play a role in addressing broadband access and the adoption gap within local communities beyond the walls or boundaries of the institution itself. Anchor institutions can lower the initial barriers to connectivity and expose users to the array of services available online, potentially serving as an on-ramp to the internet and generating additional demand. Further, the presence of anchor institutions requiring connectivity in a remote or rural community drive the buildout of network infrastructure to that community, lowering the marginal cost of providing connectivity to nearby homes or businesses and creating a more favourable economic case for offering service within the community.

Recognizing these benefits, policymakers have supported efforts to expand connectivity at anchor institutions. For example, the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) partnered with Liquid Telecom to provide internet access to 46 libraries across 29 counties (Liquid Intelligent Technologies 2016). Notably, internet access in the connected libraries was free for children under age 14 and capped at no more than USD 0.14 per visit for adults. More broadly, CA has partnered with Kenya’s library system to transform libraries into e-resource centres with connectivity, devices, and software for persons with disabilities in increase inclusivity and has also implemented a project to improve internet connectivity in nearly 900 public secondary schools (CA 2024).

The value of connectivity via anchor institutions is valued such that public officials have taken action to ensure connectivity even when such institutions are unavailable. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Jakarta, Indonesia launched a program to provide free Wi-Fi to densely populated residential areas. The program allowed residents to continue using essential government services, educational platforms, and communications applications during a period of closures for anchor institutions such as schools, libraries, and government buildings (Association for Progressive Communications 2024).

Policymakers should continue to embrace and expand the use of anchor institutions as foundational components of strategies to increase broadband demand and adoption. Specific policy measures – as well as global examples of the impact of anchor institutions’ broadband initiatives – will be explored later in this module.

Strategies to increase demand through value creation

As discussed, many people opt not to utilize connectivity services – as of 2024, there are 3.1 billion people with mobile internet coverage who do not use it (GSMA 2024b). While reasons for not subscribing to broadband may vary, policymakers worldwide pursue actions to encourage take-up and demonstrate value by addressing key barriers to adoption including affordability, digital literacy, and the perceived value of connectivity technologies to consumers. This section will detail various factors, policies, and programs that have the potential to promote take-up while also driving economic growth, fostering access to online services, and addressing the digital divide.

End-user subsidies

The cost of internet access remains one of the largest barriers to universal connectivity goals. While numerous ideas exist on how to decrease broadband costs, as further detailed in [the article on Access and Affordability], it is important to consider the impact of cost on demand and value creation. In many countries, the high cost of internet access is a top reason for low service adoption – even when the service is readily available. In Brazil, 29% of individuals not using the internet named cost as their biggest demand inhibitor; in Zimbabwe, that number was 40.1% (ITU 2022). Countries have addressed these challenges via user-access subsidies, tariffs on broadband rates, or other programs to lower the cost of the service, as well as through subsidies and reducing taxes on end-user devices.

Colombia presents an example of the benefit of end-user subsidies on demand. Before 2016, users were subject to a 16% value-added tax (VAT) on mobile data, SIM cards, and devices. This contributed to a mobile penetration rate that was lower than many of Colombia’s Latin American peers – below 30 per cent in 2014 and 66 per cent in 2016 (GSMA 2016; GSMA 2017, 13). This, in part, led the government to enact a series of tax reforms. These reforms led to the elimination of VAT on mobile devices and computers that were below certain cost thresholds. These reforms have been credited with increases in device ownership rates and demand for Internet and data consumption (A4AI 2020). By 2023, mobile connectivity penetration was estimated at 71 per cent and smartphone adoption at 76 per cent (GSMA 2023, 9).

Despite the demonstrated impact of end-user subsidies on device ownership rates and internet demand, it is important to recognize that subsidized services and devices may remain too expensive for some consumers. In these cases, governments can explore other measures—such as collaborations with the private sector—to provide customers with alternative solutions for device financing and targeted offers for underserved populations.

Digital literacy

To address low digital literacy levels, many countries have prioritized efforts to educate citizens on internet-based tools, activities, and overall benefits to combat digital skills gaps. These efforts have the potential to drive multiple facets of demand: increasing the perceived relevance and value of broadband connectivity. In Saudi Arabia, digital inclusion strategies are a key component of the country’s strategic vision for 2030. Specifically, two initiatives in the country’s development strategy are focused on digital awareness and outreach:

- Digital service awareness: launching a public awareness campaign to increase the adoption of digital government services; and

- Digital service reach: leveraging training institutions to share knowledge of digital government platforms and non-digitally literate citizens on how to use them (Government of Saudi Arabia 2024).

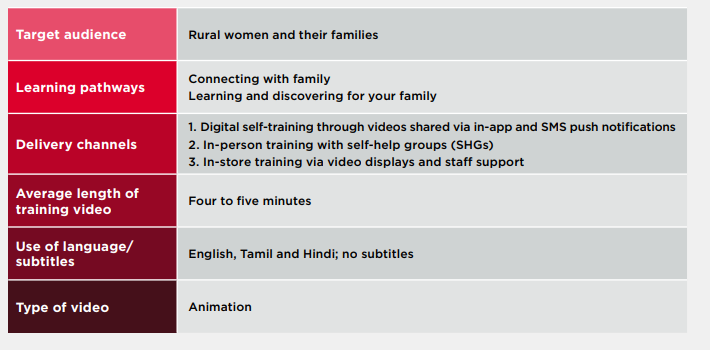

There are also examples of the private sector playing a role in digital outreach and education. In 2019, the GSMA launched a program to trial digital skills training in low- and middle-income countries in partnership with mobile operators Reliance Jio in India and MTN in Ghana (GSMA 2024a). The characteristics of the trial programme in India are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Characteristics of India digital skills pilot programme

Source: GSMA

Source: GSMA

As shown in Figure 3, effective digital training and education programs are targeted, intentional, and accessible through synchronous and asynchronous means. Similar design principles were followed during the GSMA’s trial with MTN – in Ghana, the program targeted urban and peri-urban youth through in-person, two-to-three-minute training videos on staying connected and entertained as well as skill development for business. Notably, the two trials demonstrated success and satisfaction from participants – in India, 66% of participants reported acquiring new skills from the training videos, and 58% of participants reported an increased usage of the internet; in Ghana, these numbers were 81% and 60%, respectively (GSMA 2024a). Combined, these examples suggest that policymakers should consider the value of both public and private sector initiatives to expand digital education and awareness programs.

Supporting anchor institutions

As detailed above, anchor institutions play an important role in providing connectivity to communities and promoting broadband demand. These institutions serve as community hubs and can serve as individuals’ introduction to the internet and available online content and services. As such, providing adequate resources to anchor institutions increases their ability to not only execute their core missions, but also drive network deployment and enable efforts to raise awareness about the benefits of broadband. Specific strategies to best enable anchor institutions to increase exposure to broadband benefits will vary by multiple factors including institution type, community, and available resources. However, examples can include:

- ensuring adequate middle-mile connectivity to anchor institutions, streamlining the distribution of last-mile connectivity;

- enabling citizen access to government services, demonstrating benefits of accessing services online;

- training citizen-facing staff on service use and on provision of training to community members; and

- planning and budgeting for ongoing connectivity, equipment maintenance and upgrades, and updated training.

In Romania, the Biblionet programme helped transform libraries into designated community hubs for 21st century services. The programme – which was carried out from 2009-2014 – provided internet access to over 80% of libraries and allowed 600,000 users to connect to the internet for the first time. It also trained thousands of librarians on how to provide services to citizens using the new technology and operationalised an on-going training program to continue developing the skills of local librarians (European Commission 2016). Through these efforts, the program demonstrated tangible results for several different communities in Romania; in the agriculture sector, over 90,000 farmers were able to file applications for subsidies that totalled USD 115 million of aid. For citizens more broadly, the program trained over 10,000 citizens and 90 librarians about financial literacy fundamentals (Fried, Popova, Dąbrowska, and Chiranov 2014).

The Biblionet Program is a prime example of the impact of anchor institutions – by providing connectivity services to communities, anchor institutions can showcase the benefits of the internet, help promote universal service goals, and help encourage citizens to sign up for broadband at home.

E-government

E-government initiatives, which involve the provision of government services online, are another potential tool to boost broadband demand. As governments continue to revolutionise their digital platforms for services such as permit applications, tax filings, license renewals, and more, citizens, businesses, and other stakeholders are incentivized to use the internet to access government services online.

Additionally, e-government services can also play a role in fostering digital literacy and education efforts. By providing training tools such as videos, guides, and in-person assistance, e-government efforts can help empower citizens with the skills necessary to utilize other digital platforms and tools.

The government of Estonia has released a series of e-government services through its “e-Estonia” initiative to drive digitalisation and improve digital skills. e-Estonia offers digital identification, secure electronic voting, simple online tax forms, and a digital assistant that guides citizens through online processes and services (e-Estonia 2021). As a result of Estonia’s focus on digital transformation, including the e-Estonia initiative, 93% of Estonia’s population uses the internet and Estonia has the 38th highest percentage of internet users in the world (World Bank 2023). Brazil’s Strategy for Digital Transformation offers another example of using e-government services to increase broadband demand. In 2022, the Brazilian government launched an initiative to digitise 68 public services through the creation of a central portal for citizen services. The portal allows Brazilians to access a wide array of government services including driver’s license renewal, applications for welfare benefits, and tax payments (ITU 2023).

The role of e-government services in generating demand is not limited to individual end users. If government agencies transition business-related services to an online platform, businesses may be incentivised to employ online services to establish and continue operations. In the case of a complete transition to an online platform, regulatory agencies would effectively mandate that businesses obtain or have access to an internet connection in order to continue operations.

Both examples illustrate the role of e-government services as a driver of broadband demand. As governments continue to adapt their services, it is important that policymakers consider the myriad benefits associated with moving essential services online. These services can reduce costs, eliminate inefficiencies, and demonstrate the importance of connectivity to citizens who may not be interested in getting online.

Content

Consumer interests also play a key role in increasing broadband demand. Content – whether it be through streaming services, social media, or other channels – has a significant and positive impact on broadband adoption (Viard, Economides 2014). Further, the availability of local language content is another driver of broadband demand, making online content more accessible to users who are more comfortable – or perhaps only comfortable – in a language other than widespread languages such as English, French, or Spanish, making it inaccessible to many parts of the world where rural, low-income, or other disadvantaged groups are more prevalent (Web Technology Surveys 2021). This indicates a significant opportunity to increase the amount of content available in other languages to meet the needs of – and therefore drive demand among – populations in which other languages are dominant. In India, 98 percent of internet users have accessed content in Indic languages and 57 percent of internet users indicated a preference for accessing content in Indic languages in urban India (KANTAR and IAMAI, 2024).

In addition to local language content, the impact of streaming services on broadband demand is also notable (Srinan and Bohlin 2013). Streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime have helped to increase broadband connectivity. In markets without an existing video streaming service, a new service launch is associated with a 13.9% increase in broadband adoption – and in markets with only a single streaming video platform, the introduction of a second service resulted in a 7% increase in broadband adoption. These increases continue as more platforms are made available, albeit with diminishing returns and potential impacts dependent on the level of economic development within the market (Katz, Jung, Callorda 2024). In addition, a consumer benefit increase due to expanded video streaming offerings has been observed – 48% in an average country after 10 years. Notably, these two trends – the availability of local language content and the presence of streaming video services – continue to overlap, as many streaming platforms have expanded offerings of local language content in recent years.

Lastly, social media platforms, video sharing applications, and messaging services can create a network effect that increases broadband demand. On platforms such as Facebook that encourage their users to add their friends, family members, and connections, offline users may be encouraged by peers to join the platform. The same is true for messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram, where direct connections can influence offline users to join the platform – and importantly, to subscribe to the internet connection needed to use it.

Support for small and medium enterprises

In addition to targeting end users, policymakers may consider the potential to stimulate demand for broadband services among small and medium enterprises (SMEs). While the number of SMEs and their potential demand for broadband connectivity will vary widely across countries, regions, and between rural, suburban, and urban contexts, there is a potential opportunity to implement policies or programmes that provide SMEs with skills and knowledge that generate a lasting demand for broadband connectivity.

Policies that target increased SME demand for broadband service in some ways mirror policies targeting individual users or specific populations. For example, policies that result in increased digital skills, advisory services tailored to business needs, and knowledge exchanges may better prepare small businesses to leverage online services to operate or market their businesses more effectively (Henderson 2020). These could take the form of training, workshops, business advisory services, and demonstration centres. In an approach that is analogous to end-user subsidies, financial support to SMEs in the form of subsidies, tax benefits, or other financial incentives may enable small businesses to overcome financial barriers to obtaining and leveraging broadband connectivity related to the conduct of their business. In addition, as discussed above, e-government services may also encourage SMEs – and larger businesses – to conduct certain transactions online, such as business licensing or registration or tax payment.

Policies and programmes intended to generate demand for connectivity among SMEs may draw upon resources from ministries, regulators, and other stakeholders across multiple sectors. For example, a programme that includes a component to drive broadband adoption among small manufacturers could be supported by resources from ministries responsible for both digital connectivity and industry or manufacturing. The potential for collaboration between government ministries or agencies may increase the array of options available for driving broadband demand by SMEs.

Key issues for considerations

As illustrated throughout this module, there are many different policy actions, programs, and initiatives being used around the world to drive broadband demand. Many of these programs are focused on the consumer level, as content platforms, end-user subsidies, and digital education can directly influence an individual’s desire to get online. Further, the perceived value of broadband – which can be shaped by the availability of relevant, interesting, and productive internet applications and content – can directly influence an individual’s decision to subscribe to broadband services. On the other hand, there are numerous institutionally focused action items such as launching e-government initiatives and supporting anchor institutions that represent specific opportunities for policymakers to create opportunities for broadband value creation.

Content platforms such as streaming services, social media, and messaging services play a role in driving broadband demand. These platforms provide users with unique content experiences that are only available online. Services that offer local language and locally relevant content have the potential to increase demand even further.

E-government platforms and services are another way to increase broadband demand among consumers. By digitalising government services, governments can streamline their bureaucratic processes while also providing citizens with a demonstrated reason to get online. However, e-government platforms should also be implemented alongside efforts to educate the public on how to benefit from these services.

These platforms can be used for digital identification, taxes, applications, and permits, and should be considered as a way to reduce red tape and improve efficiencies. Policymakers should consider implement educational efforts through anchor institutions to inform communities on how to use the newly introduced services. These educational efforts also help improve general digital skills, providing an opportunity for governments to leverage anchor institutions to increase broadband demand and digital literacy.

Digital education is a key component to increasing demand and demonstrating the value of broadband services. Raising awareness about the benefits of broadband and how to use it in a safe and productive manner requires policymakers to invest in dedicated programs and campaigns. These programs should be tailored with specific demographics in mind and should offer in-person and asynchronous components to allow targeted individuals to learn digital skills at their own pace. Further, policymakers can leverage anchor institutions and the private sector to advance these efforts, working together with a range of stakeholders to develop digital skills programmes that are tailored to the local context.

Key Findings: Increasing demand for broadband through value creation and targeted initiatives

|

References

Alliance for Affordable Internet. 2020. Eliminating luxury taxation on ICT essentials. Washington DC: A4AI. https://a4ai.org/research/eliminating-luxury-taxation-on-ict-essentials/. https://www.ampereanalysis.com/insight/more-than-half-of-netflixs-content-spending-now-outside-of-north-america.

Association for Progressive Communications (APC). 2024. Free and Public WiFi Initiatives in Africa, Asia and the Pacific. Johannesburg: APC. https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/free-and-public-wifi-initiatives-in-africa–asia–and-the-pacific_final.pdf.

https://www.benton.org/publications/connecting-anchor-institutions-broadband-action-planBroadband Commission for Digital Development. 2021. 21st Century Financing Models for Bridging Broadband Connectivity Gaps. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://broadbandcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2021/11/21st-Century-Financing-Models-Broadband-Commission.pdf.

Broadband Commission for Digital Development. 2023. The State of Broadband: Digital connectivity, a transformative opportunity. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://broadbandcommission.org/publication/state-of-broadband-2023/.

Broadband Commission for Digital Development. 2024a. What is Universal Connectivity?. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.broadbandcommission.org/universal-connectivity/#:~:text=The%20Broadband%20Commission%20published%20the,2030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development.

Broadband Commission for Digital Development. 2024b. The State of Broadband: Leveraging AI for Universal Connectivity, Part One. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://broadbandcommission.org/publication/state-of-broadband-2024/.

Communications Authority of Kenya (CA). Accessed November 2024. Universal Access Overview. https://www.ca.go.ke/universal-access-overview.

e-Estonia. 2021. Estonia – a European and global leader in the digitalisation of public services. Tallinn: e-Estonia. https://e-estonia.com/estonia-a-european-and-global-leader-in-the-digitalisation-of-public-services/.

European Commission. 2016. Biblionet – Global Libraries Romania. Brussels: European Commission. https://epale.ec.europa.eu/ro/blog/biblionet-biblioteci-globale-romania.

GSMA. 2016. Digital Inclusion and Mobile Sector Taxation in Colombia Reforming sector-specific taxes and regulatory fees to drive affordability and investment. London: GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/about-us/regions/latin-america/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Taxation-Colombia-Full-Report_ENG.pdf.

GSMA. 2017. Country overview: Colombia. London: GSMA. https://data.gsmaintelligence.com/api-web/v2/research-file-download?id=28999732&file=Country%20overview%20Colombia.pdf.

GSMA. 2023. The Mobile Economy in Latin America 2024. London: GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-economy/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/The-Mobile-Economy-Latin-America-2024.pdf.

GSMA. 2024a. A needs-based approach to mobile digital skills training: Learnings from India and Ghana. London: GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/A-needs-based-approach-to-mobile-digital-skills-training.pdf.

GSMA. 2024b. The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2024. London: GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/The-State-of-Mobile-Internet-Connectivity-Report-2024.pdf

Henderson, Dylan. 2020. Demand-side broadband policy in the context of digital transformation: An examination of SME digital advisory policies in Wales. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7397941/.

International Telecommunications Union. 2022. Individuals not using the Internet, by type of reason. Geneva: ITU. https://datahub.itu.int/data/?i=100006.

International Telecommunications Union. 2023. The State of Broadband 2023. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/pol/S-POL-BROADBAND.28-2023-PDF-E.pdf.

Internet Society Foundation. 2023. A more inclusive Internet for who? Non-English speakers in digital spaces. https://www.isocfoundation.org/2023/02/a-more-inclusive-internet-for-who-non-english-speakers-in-digital-spaces/.

KANTAR and IAMAI. 2024. Internet in India 2024. https://www.iamai.in/guest-checkout/NzY1Ng==.

Liquid Intelligent Technologies. 2016. Liquid Intelligent Technologies Kenya moves national libraries online to offer free internet to public. https://liquid.tech/about-us/news/liquid_intelligent_technologies_kenya_moves_national_libraries_online_to_offer_free_internet_to_public/.

National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Economics of Broadband Networks. Washington: NTIA. https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/Economics%20of%20Broadband%20Networks%20PDF.pdf.

Raul Katz, Juan Jung, and Fernando Callorda. 2024. The role of Video on Demand in stimulating broadband adoption. Telecommunications Policy. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S030859612400048X.

Sandra Fried, Desislava Popova, Małgorzata Dąbrowska, and Marcel G. Chiranov. 2014. A Tale of Public Libraries in Bulgaria, Poland, and Romania: The Case of Three Gates Foundation Grants. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/92036/bitstreams/300472/data.pdf.

Srinuan, Chalita and Erik Bohlin. 2013. Analysis of fixed broadband access and use in Thailand: Drivers and barriers. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308596113000438.

V. Brian Viard, Nicholas Economides. 2014. The Effect of Content on Global Internet Adoption and the Global “Digital Divide”. New York: Management Science. https://neconomides.stern.nyu.edu/networks/The_Effect_of_Content_on_Global_Internet_Adoption.pdf

Web Technology Surveys. 2021. Usage statistics of content languages for websites. https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language.

World Bank. 2023. Individuals using the Internet (% of population). Washington: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?end=2023&most_recent_value_desc=true&start=1960&view=chart&year_high_desc=true.

Last updated on: 09.09.2025