Policies to promote inclusion

01.09.2025Cross-sectoral policies: digital skills and literacy

Universal access (UA) policies – and more recently, universal and meaningful connectivity (UMC) policies – have evolved to extend beyond the information and communications technology (ICT) sector itself, more broadly including cross-sectoral approaches that can leverage ICT benefits across multiple economic segments. The ideas of empowering users and leading to positive impact are arguably the ultimate goals of cross-sectoral policies intended to improve and expand the use of ICTs to achieve broader development goals.

Perhaps the most prominent example of cross-sectoral thinking is demonstrated by the inclusion of digital skills in UMC policies and plans, as well as the inclusion of such ICT skill-building in plans and policies in other sectors. ITU has identified the benefits of building digital skills in the context of everyday life and in the context of work (ITU 2024a):

- Skills for life, or skills required to fully participate in the digital society and digital economy. Basic skills allow individuals to access news and information; communicate with friends and family; join new communities; access government, health, financial, and other electronic services; learn new skills; and play games, among other benefits. Individuals with basic skills are also better equipped to protect themselves from scams, misinformation, and other digital harms.

- Skills for work, or skills that improve opportunities for success in work. These include:

- General digital skills: Skills expected by many professions that allow people to be productive in a variety of work settings.

- Domain-specific skills: Skills needed for particular sectors (e.g., healthcare, tourism, or agriculture) and for particular jobs (e.g., accounting, data entry, or customer support).

- Advanced digital skills: Skills needed to be an IT professional, including programming, database management, cybersecurity, data analysis, and digital design.

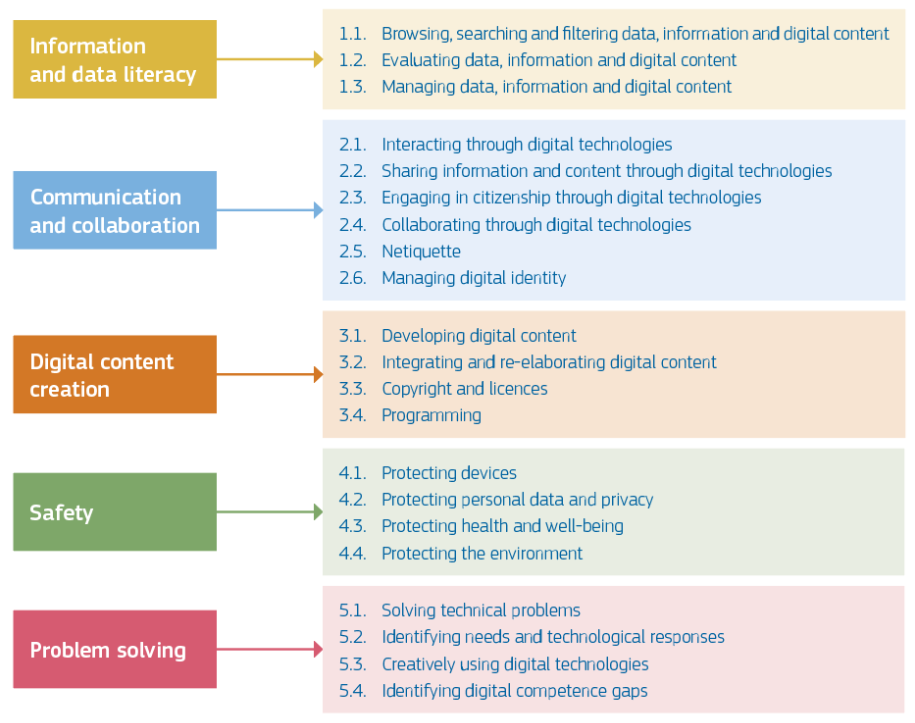

In its 2024 Digital Skills Toolkit, the ITU refers to the European Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp), noting that it is research-based, has evolved through extensive stakeholder involvement, and has gained wide popularity around the world (ITU 2024a). DigComp incorporates a broad consideration of digital skills, including areas of competence that extend well beyond the use of particular software or technology tools (Figure 1).

Figure 1. DigComp conceptual model

Source: European Commission, 2022.

These definitions and frameworks are useful as reference points for policy-makers determining the digital skills and cross-sectoral components of UMC plans. The application of high-level conceptual models avoid the adoption of digital skills approaches that are narrowly defined or quickly outdated due to technological change. Instead, broader considerations allow for the incorporation of new technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), and emerging online concerns, such as addressing misinformation and disinformation.

While digital skills may be most applicable to the different stages of educational and professional development indicated, they can be introduced and taught at different developmental points.

Uruguay’s Plan Ceibal (Basic Informatic Educative Connectivity for Online Learning), was created in 2007 to foster inclusion and equal opportunity while supporting educational policies with technology. Beyond supplying students with computers and connectivity, the initiative also provides programmes, educational resources, and teacher training intended to better incorporate technology into the educational process. An outgrowth of Plan Ceibal, Jóvenes a Programar enables advanced skills by providing training in software testing and common programming languages to Uruguayans between the ages of 18 and 30 who successfully complete their secondary education. The goal of Jóvenes a Programar is to expand inclusion in the technology industry, while encouraging students to apply computational and logical thinking to new areas. Recent iterations of the Jóvenes a Programar focused on issues such as addressing the gender gap in the IT industry, increasing women’s access to ICTs, and facilitating ICT access to residents of Uruguay’s rural interior.

In some cases, technology-enabled activities are used to encourage ICT-related skills such as logical thinking, reasoning, and sequencing at the pre-school level. See, for example, Singapore’s various programmes to increase exposure to digital skills through the educational system.

As highlighted in the ITU’s Digital Skills Toolkit, advanced skills can be provided through a wide range of trainers, including employers, technical and vocational schools, bootcamps and other commercial training programmes, and makerspaces (ITU 2024). In some cases, training is sponsored by a government, but provided through technical schools, vocational schools, or universities.

It is noteworthy that such initiatives often do not fall under the umbrella of a UA policy, even though they address digital skills needs. The use of a cross-sectoral component such as digital skill-building creates beneficial ripple effects across entire economies, expanding economic opportunities and strengthening communications regardless of the industrial sector, geographic location, or population group. Beyond access to ICTs, ensuring that their potential benefits can be leveraged across multiple sectors magnifies their impact and should be a key component of a modern UA policy or programme that may, in turn, take into account coordination with ministries and agencies outside the ICT sector.

The potential of improved digital skills development cannot be understated. As the Broadband Commission notes, closing the broadband coverage gap in Africa by 2030 would mean that millions of citizens will access the Internet for the first time. It will be critical to help these new users to understand the value of the Internet and how to use it, as well as to build their digital resilience (Broadband Commission 2019).

Promoting local content and content industries

Another key consideration of modern UA policies is driving demand for connectivity through the promotion of relevant content. Beyond providing the connection for users to access content, a forward-looking UA policy should also consider the need to bring the newly connected online and make it relevant for them to take advantage of the connection.

While the Internet hosts a tremendous amount of public and private content, connectivity demand is driven by the availability of content that is relevant to users. This includes ensuring that content is available in relevant languages and is tailored to local needs and interests.

The importance of locally relevant content has remained a consistent component of policies to promote inclusion. The Broadband Commission states that the availability of locally generated content is key to promoting Internet use (Broadband Commission for Digital Development 2024). Further, multiple global efforts are underway to improve and expand the availability of online content and services in a wider range of languages. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is leading a United Nations effort rooted in a General Assembly resolution proclaiming 2022-2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (IDIL 2022-2032). The IDIL 2022-2023 Action Plan includes multiple activities that focus on or include components related to improving digital literacy in indigenous languages, including capacity building in media information and literacy, digital and online activism and advocacy, and digital skills related to content production (UNESCO 2022). The Coalition on Digital Impact (CODI) is a group of more than 15 organizations with a stated mission to ensure that every person can navigate the Internet in their own language. CODI is working with policy-makers, industry, and non-profit organizations to reduce language, literacy, and cultural barriers to Internet access; enable universal acceptance of domains and scripts online; and advance policies that promote access (CODI 2025).

The role of a UA policy in this context is to support efforts that enable local content creation. In one example of such an approach, Nigeria’s 2020-2025 National Broadband Plan includes efforts to bring more Nigerian businesses online through free .ng domain name registrations for two years, and through multiple digital literacy and awareness approaches intended to spur demand (Government of Nigeria 2020). Both types of efforts foster increased local content availability. The free domain name registration initiative is intended to promote local content development as well as job creation and expanded online business opportunities for Nigerian companies through a reduction in the cost of establishing a new online business or online presence. Notably, the policy does not direct funds to particular businesses or industries, but rather seeks to provide a universal benefit to all Nigerian businesses seeking to register a domain name, allowing them to direct their resources toward other aspects of developing their business. Responsibility for the implementation of such initiatives is spread among various government agencies, with Ministry of Communications and Digital Economy participation included in all of the digital literacy activities, while the domain name registration programme is assigned to Nigeria’s Internet registry association, the IT development agency, and the corporate affairs commission. As is seen in this case, approaches to expanding digital literacy and content creation involve a range of stakeholders.

In recent years, numerous countries have included local content provisions in digital development strategies, digital economy plans, national broadband plans, and digital transformation strategies, among other instruments. Vietnam’s National Digital Transformation Program includes digital content development among the sectors to be developed in support of the national digital economy (Government of Vietnam 2020). As described in the program, digital content development should include digital communications products, digital advertisements, and the promotion of a diverse and appealing digital content ecosystem. The program also references the importance of creating a fair and equal competitive environment for Vietnamese digital content enterprises.

Similarly, Nigeria’s digital literacy-related efforts also include development of educational, vocational, and entrepreneurial content in local languages. Nigeria’s plan also envisions development and implementation of an enhanced national digital virtual e-library that provides a range of digital resources and includes translation of foreign-language material to local languages.

In conjunction with the development of local-language content, there may be a need to consider how to deliver such content to populations lacking traditional literacy and numeracy. A UNESCO-sponsored literature review identified eight key design themes that have been incorporated into digital solutions for users with low literacy and digital skill levels (Zelezny-Green and others 2018):

- use of voice/speech-based computing interface;

- substantial incorporation of graphics;

- use of relationship-based and non-linear user interfaces;

- local or locally relevant content is important for interactive technology adoption by people with low literacy or digital skill levels;

- integration of social/sharing elements to bolster the adoption and spread of technologies;

- designs targeted to people with more education/higher literacy are sometimes useful for people with lower education or literacy levels;

- participatory design methodologies, including codesigning solutions, work best when creating digital solutions for low-literate and low-skilled populations; and

- digital solutions designed for more than one user, especially when a user with more skills/higher literacy is helping someone less proficient with technology, can help lower barriers.

Such considerations can be incorporated into the components of UA or related policies that address emphasizing local or relevant content in order to ensure that it is accessible to the widest range of potential users.

Additional approaches to local content development can include efforts to increase the online availability of government services and information. As a major producer of information that is both locally relevant and presented in the local language, national, state, and local governments are ideally suited to play a role in the implementation of UA policies that create new or expanded online resources that provide useful information to citizens.

Overall, UA policies should consider the potential benefit of increased availability of local and locally relevant content in terms of increasing Internet usage. In crafting goals or action items intended to increase the availability of local content, policy-makers should consider the roles of both the private sector and the public sector in order to maximize the impact of such efforts.

Gender inclusion and accessibility policies

Recognizing that lack of Internet access or usage is not uniform across populations, policy-makers should consider how UA policies and universal access and service funds (UASFs) can be employed to assist those groups with comparatively lower levels of access and usage. In particular, research has identified a need to improve connectivity and digital services access for women and for people with disabilities (PWDs).

Based on 2024 ITU estimates, there was a five per cent difference in Internet penetration between men and women worldwide, although the number varies across regions and income levels (ITU 2024b). Notably, while the global gender parity score has continued to increase over the last five years, LDCs are an exception. Considering only those countries, gender parity decreased over the same period, from 0.74 to 0.70. Gender parity has been achieved in the Americas, Europe, and the CIS region. In the Asia-Pacific region, progress is fast, as the score improved from 0.89 in 2019 to 0.95 in 2024. In the Arab States, on the other hand, the gender parity score has not improved, remaining at 0.86 during the same period. Finally, there is progress in Africa, but the region is still far behind the other regions.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) notes that the gender gap, sometimes known as the digital gender divide, has multiple root causes, including barriers to access, affordability, education, and lack of technology literacy (OECD 2018). While these aspects are relevant to the digital divide across groups, the OECD also notes the relevance of gender biases and socio-cultural norms leading to gender-based digital exclusion. These can include comparatively higher domestic work and childcare obligations and negative social perceptions of Internet use by women and girls.

Organizations including the Broadband Commission and the World Wide Web Foundation have proposed policy approaches to close the gender gap. Among the four recommendations presented by the Broadband Commission’s Working Group on the Digital Gender Divide was the integration of a gender perspective in strategies, policies, plans, and budgets (Broadband Commission 2017b). This recommendation grows from the recognition that gender-related policies, strategies, and action plans often fail to acknowledge the importance of ICTs and broadband as enabling tools, while broadband strategies, policies, and plans often fail to include a gender dimension. To that end, the working group suggested three primary action items to address this disconnect:

- establishing gender equality targets for Internet and broadband access and use;

- assessing strategies, policies, plans, and budgets for gender equality considerations; and,

- consulting and involving women as well as relevant local communities and experts.

Such approaches are particularly salient for the development or revision of UA policies, increasing the likelihood of addressing the gender gap alongside improving overall connectivity and access.

The World Wide Web Foundation has also identified universal access and access funds (UASFs) as an “untapped resource” for addressing the gender digital divide (Thakur and Potter 2018). To that end, the organization has proposed four key recommendations to improve the efficiency and efficacy of UASFs, namely, to address the gender gap:

- Invest at least 50 per cent of funds in projects targeting women’s Internet access and use.

- Make project design and implementation more gender responsive.

- Increase transparency of fund financing, disbursements, and operations.

- Improve diversity in UASF governance and increase awareness of gender issues within the UASF.

A recent example of this approach is Colombia’s 2023-2026 National Digital Strategy, which includes a section on using ICTs as a tool for closing the gender gap and promoting the inclusive and equitable use of digital technologies (MinTIC 2024, 44). The plan underscores the importance of improving both women’s access to and adoption of ICTs, and notes the need to address the socio-cultural norms and beliefs that discourage women from using ICTs or pursuing ICT-related careers.

Ghana’s government has introduced and supported programmes intended to advance women’s use of technology and Internet-enabled services. Ghana’s UASF, the Ghana Investment Fund for Electronic Communications (GIFEC), is tasked with facilitating the implementation of universal access to electronic communication and the provision of Internet points of presence in underserved and unserved communities, facilitating capacity-building programmes, and promoting ICT inclusion in unserved and underserved communities, and the deployment of ICT equipment to educational, vocational and other training institutions. GIFEC’s efforts have included a commitment to train 2,000 girls in coding in commemoration of International Girls in ICT Day 2020 (April 23, 2020), in association with Cisco, followed by the July 2024 launch of the “Girls in ICT Trust” nonprofit, which aims to provide comprehensive ICT training and support to more than 9,000 young women annually across all of Ghana’s regions. GIFEC has also supported the Digital for Inclusion (D4i) joint initiative with other national and international stakeholders to expand Ghana’s digital economy, financial inclusion, and economic opportunities for underserved and financially excluded populations. D4i set specific targets of reaching 60 per cent of women in targeted areas.

In addition to the gender gap, there are also access disparities that affect PWDs. While ICTs play a significant role in overcoming barriers faced by PWDs in terms of participating actively in society, technological progress does not guarantee equal access to new and improved technologies. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) notes that UASFs are a valuable resource that can be used to fund programmes to assist PWDs in the Caribbean (Bleeker 2019), a view that is equally valid in other regions.

Among various action items that more broadly suggest operational improvements to universal service funds, ECLAC proposes several action items to close access gaps for PWDs. These include:

- enable funding to be disbursed to civil society and non-governmental organizations working with PWDs and other marginalized groups;

- include a stronger mandate for PWDs, including an obligation to have annual targets to meet fund objectives;

- increase engagement with PWDs at each stage of a project’s lifespan, including the identification, appraisal, and allocation process;

- increase representation of PWDs in UASFs; and

- invest a fixed percentage of funds in projects to increase access to technology for PWDs.

It is noteworthy that there is significant overlap between the World Wide Web Foundation’s recommendations for addressing the gender gap and ECLAC’s recommendations to improve access for PWDs, and that the D4i initiative in Ghana includes not only targets for reaching women, but also for reaching 10 percent of PWDs in targeted areas. These may point to common approaches to addressing access gaps among other marginalized populations.

“Towards building inclusive digital communities”

The ITU toolkit and self-assessment for ICT accessibility implementation is addressed to every stakeholder involved in the digital transformation process, from policy-makers, regulators, and ICT leaders in the private sector, to members of academia, end-user organizations, industry, and entrepreneurs. This resource provides all these stakeholders and other interested parties the information needed to guarantee that everyone addresses the necessary policy-making, regulatory and strategic implementation components from their respective fields. It enables stakeholders to effectively assess and track their progress in the implementation of digital inclusion initiatives by providing back to back tailored expert advice in line with global commitments on inclusion set by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals.

References

Bleeker. 2019. Using Universal Service Funds to Increase Access to Technology for Persons with Disabilities in the Caribbean. Studies and Perspectives series, ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean, No. 79(LC/TS.2019/59-LC/CAR/TS.2019/2). Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/events/files/series_79_lcarts2019_2.pdf.

Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development. 2017a. Working Group on Education: Digital skills for Life and Work. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://broadbandcommission.org/Documents/publications/WG-Education-Report2017.pdf.

Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development. 2017b. Working Group on the Digital Gender Divide: Recommendations for Action: Bridging the Gender Gap in Internet and Broadband Access and Use. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.broadbandcommission.org/Documents/publications/WG-Gender-Digital-Divide-Report2017.pdf.

Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development. 2019. Connecting Africa Through Broadband A Strategy for Doubling Connectivity by 2021 and Reaching Universal Access by 2030. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.broadbandcommission.org/Documents/working-groups/DigitalMoonshotforAfrica_Report.pdfCoalition on Digital Impact (CODI). Accessed 2025. https://www.codi.global/.

Government of Nigeria. 2020. Nigerian National Broadband Plan 2020-2025. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Communications and Digital Economy. https://www.ncc.gov.ng/docman-main/legal-regulatory/legal-other/880-nigerian-national-broadband-plan-2020-2025/file.

Government of Vietnam. 2020. Decision No. 749/QD-TTg of the Prime Minister: Approving the “National Digital Transformation Program to 2025, with a vision to 2030.” https://chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=200163.

Intel. 2011. The Benefits of Applying Universal Service Funds to Support ICT/Broadband Programs. Santa Clara: Intel Corporation. https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/white-papers/usf-support-ict-broadband-programs-paper.pdf.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2024. Digital Skills Toolkit. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Digital-Inclusion/Documents/ITU%20Digital%20Skills%20Toolkit.pdf.

ITU. 2024a. Digital Skills Toolkit. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. https://academy.itu.int/sites/default/files/media2/file/2401045_1f_Digital%20Skills%20Toolkit_compressed_0.pdf.

ITU. 2024b. Facts and Figures 2024: The gender digital divide. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2024/11/10/ff24-the-gender-digital-divide/.

MinTIC. 2024. Estrategia Nacional Digital de Colombia 2023-2026.. Bogota: Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. https://www.mintic.gov.co/portal/715/articles-334120_recurso_1.pdf.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2018. Bridging the digital gender divide: Include, upskill, innovate. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. http://www.oecd.org/internet/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf.

Thakur, D., and L. Potter, 2018. Universal Service and Access Funds: An Untapped Resource to Close the Gender Digital Divide. Washington DC: World Wide Web Foundation. http://webfoundation.org/docs/2018/03/Using-USAFs-to-Close-the-Gender-Digital-Divide-in-Africa.pdf.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2022. Global Action Plan of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, (IDIL2022-2032); abridged version. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000383844.

Zelezny-Green, Ronda, Steven Vosloo, Gráinne Conole. 2018. Digital Inclusion for Low-skilled and Low-literate People. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. https://bit.ly/2RUrQz7.

Last updated on: 09.09.2025