Overview of national spectrum licensing

25.04.2025

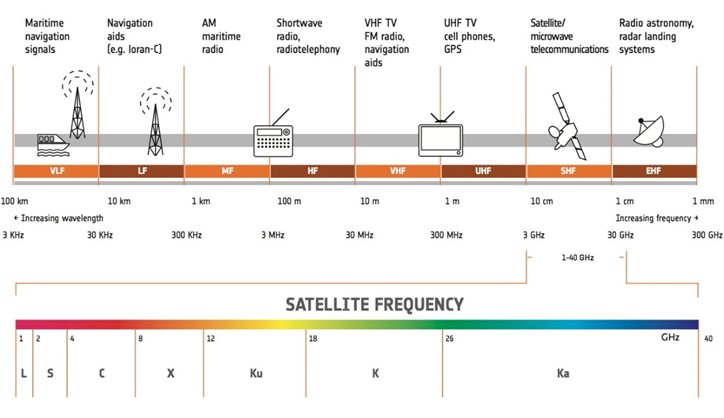

Source: ESA 2013.

As a limited natural resource, national administrations manage and assign the use of spectrum within their countries. In order to support the wide variety of different telecommunications services, as well as to mitigate possible unwanted interference, regulators issue national tables of frequency allocations and establish licensing frameworks that govern how spectrum will be awarded in the country. Regulators also intervene to mitigate disputes in cases of harmful interference along national borders. This process includes working with neighboring countries to coordinate spectrum allocations, in accordance with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations (RR), as well as possible regional agreements (e.g., the Eastern Caribbean Telecommunications Authority (ECTEL), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Asia Pacific Telecommunity (APT), European Union (EU), etc.). Mindful that there are competing demands for spectrum, the regulator’s key role is to make spectrum available across different services to meet the evolving market demands for expansion of connectivity and access to new applications, taking into account the decisions made at the international and regional levels.

Types of spectrum licenses

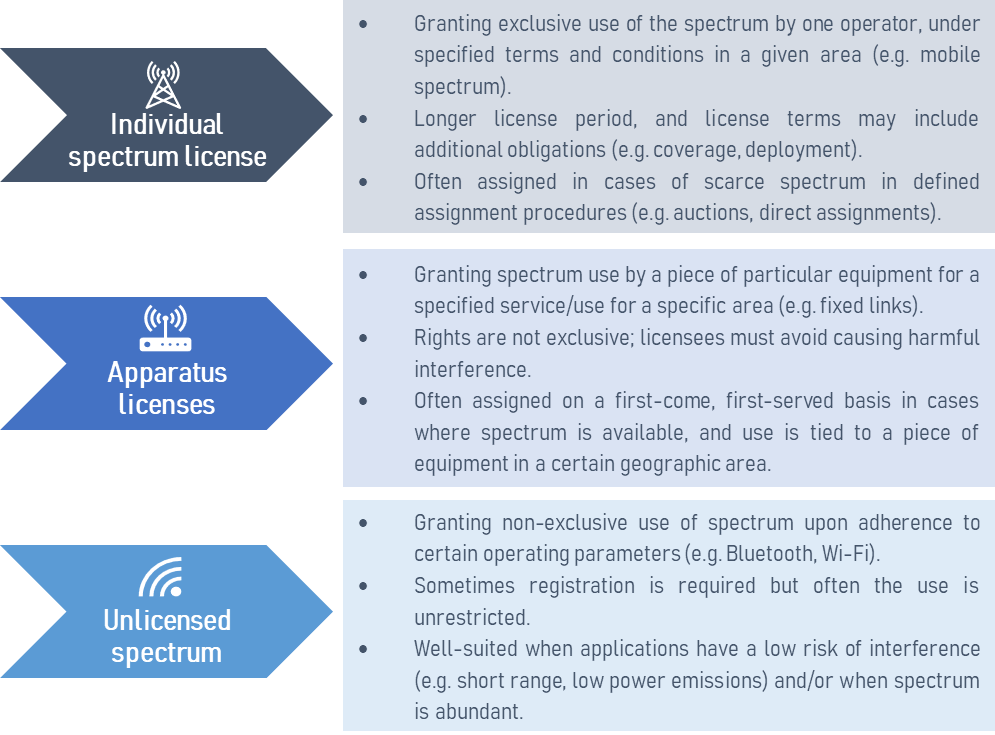

Regulators decide on the licensing mechanism to apply to spectrum by considering a band’s availability, proposed usage, and risk of harmful interference. Generally, spectrum is authorized through one of the following mechanisms:

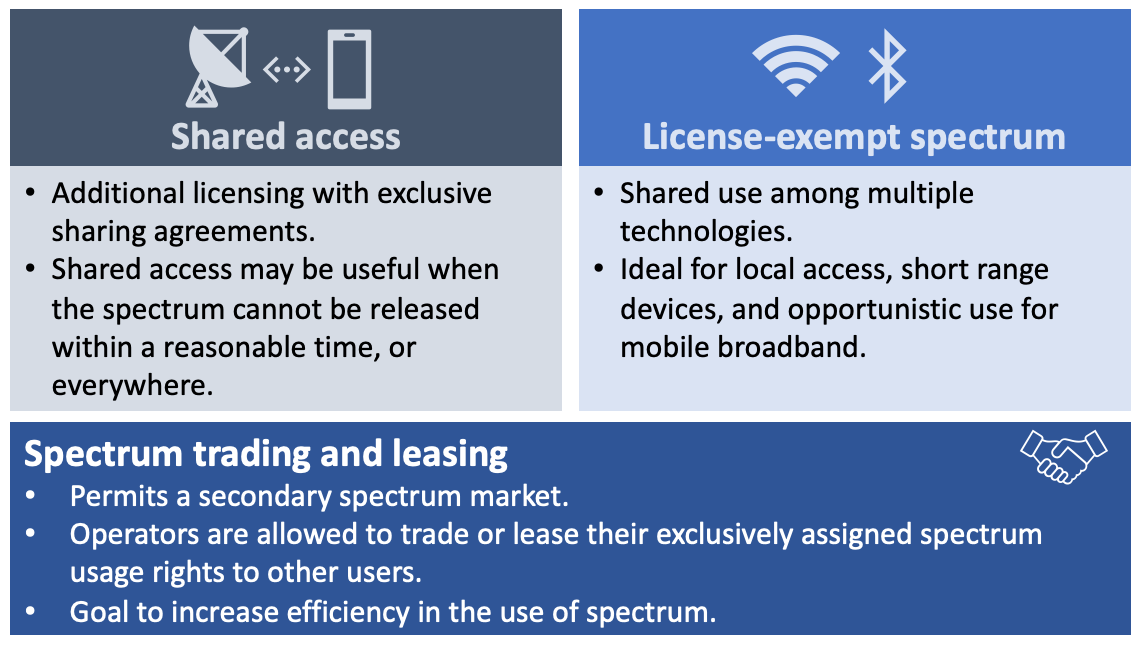

Individual spectrum, apparatus licenses, and unlicensed spectrum also could fall under a shared access framework, as part of either an unlicensed or licensed regime. In both cases, use is shared with other types of services or users in the band under requirements of non-interference.

An overarching principle that should be applied to all license types is the concept of technological neutrality. Allowing spectrum to be used by any technology permits operators to evolve as technology and the market advances and to continue to use spectrum efficiently to meet customer demand. This has been widely accepted among regulators worldwide. 61.7% of countries have introduced the concept of technology neutrality in all spectrum licenses, and roughly three fourths have incorporated neutrality in all or some licenses (ITU 2022).

Satellite systems

To gain access to spectrum, satellite operators must navigate a regulatory process governed by both national authorities and ITU. The ITU allocates spectrum globally and coordinates orbital slots to prevent harmful interference. Operators submit an application to their national regulator detailing the satellite’s technical characteristics, intended frequency bands, and coverage area. This application must align with the country’s spectrum allocation plans and comply with ITU regulations. Regulators review the proposal for compatibility with existing users and national priorities. Successful applicants often pay spectrum licensing fees and must demonstrate how their system ensures efficient use of frequencies. Coordination with other spectrum users, both domestically and internationally, is essential to finalize the licensing process and mitigate interference risks.

Equipment type approval

A foundational component of any regulator’s licensing framework is equipment type approval, or homologation. This process ensures that any device that will use spectrum adheres to agreed technical standards, which the regulator assumes will be upheld when licensing the band. Making sure a piece of equipment is operating according to technical standards is important for spectrum use across all bands, but especially so in cases where different applications are using the same spectrum band, like in shared access bands, and in case of the use of license-exempt bands.

Type approval and conformity marksDevices that use radiofrequencies (RF) are usually required to obtain type approval before its use is allowed in a specific country. Given that these devices emit radiofrequency, they are required to be tested for compliance with regulatory standards to avoid possible harmful interference. Some types of devices requiring type approval include user devices such as mobile phones, Bluetooth headsets, Wi-Fi routers, among others; and network equipment such as transmitters, antennas, switches, among others.Type approval procedures vary across different countries, but they generally require a demonstration that the device complies with the relevant technical requirements. The equipment is submitted to testing, and after its compliance is verified, it is then certified. Some jurisdictions require certain RF devices to be labelled accordingly, also called a conformity mark. For example, devices sold in Europe bear the “CE” mark, those in the United States display the FCC label, and devices in Brazil use the ANATEL mark. Finally, some countries may recognize type approvals from other jurisdictions as sufficient authorization, usually through the implementation of mutual recognition agreements (MRA).

|

Source: USA, FCC, no date, a; USA, FCC, no date, b; EC, no date; Brazil, ANATEL 2020.

Mechanisms for spectrum award

Individual spectrum licenses

Individual spectrum licenses are usually assigned through an administrative assignment or beauty contest approach, an auction approach, or a hybrid approach.

- Administrative assignment: Regulators assign spectrum to the candidates that best meet specified criteria.

- Auction: Whichever operator places the highest bid for a spectrum block wins spectrum, although the auction design may include other criteria. Different auction designs include simultaneous multiple round ascending, clock, combinatorial clock, or sealed bid auctions.

- Hybrid approach: A hybrid approach blends auction and administrative assignments. For example, a regulator may select a short-list of bidders based on administrative criteria and then hold an auction to assign spectrum among the shortlisted candidates.

Spectrum for mobile services is more commonly awarded through auctions, although there are examples of both direct assignment and hybrid approaches. Both administrative and auction approaches to spectrum licensing have advantages and disadvantages (see the table below). The best assignment approach will depend on the regulator’s policy objectives and the market conditions, including demand for the spectrum, level of competition, and the potential risks to investment and quality of service. Some regulators include aspects of both approaches to balance the risks with the benefits of each.

Comparison of spectrum assignment approaches for individual spectrum licenses

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Administrative Assignment | Inexpensive and easy to organize | Chosen bids may not necessarily be the ones that would make the best use of spectrum |

| Ability to set targeted criteria (e.g. coverage or deployment requirements) according to policy objectives | Appropriate penalties may not be defined in case of failed /unmet commitments | |

| Power to set license fees considering operators’ financial viability and capacity to invest in network | Less transparent and vulnerable to bias and corruption | |

| Often used when spectrum demand does not exceed supply | Substantial costs to prepare bidding documents may discourage potential bidders | |

| Assignment via Auction | Spectrum generally awarded to bidders who value it most | Poor auction design can lead to inefficient spectrum assignments or limit participation (e.g., high reserve prices) |

| Represents a market-value based assessment of spectrum | Can lead to very high spectrum access prices, slowing operators’ ability to deploy networks due to capital constraints | |

| Targeted criteria (e.g. coverage or deployment requirements) can be set in license terms | Few spectrum blocks available for auction can lead to decreased competition (e.g., incumbent wins only block on offer) | |

| Transparent and legally robust outcome in most cases | More costly and time-consuming to organize | |

| Often used when spectrum demand exceeds supply | Collusion still possible |

Source: TMG.

Regulators usually issue calls for tenders or proposals for individual spectrum licenses, as opposed to awarding spectrum on a rolling basis. This is because (a) the frequency bands may have existing users and spectrum is not available until existing licenses expire, (b) the spectrum may need to be reconfigured before it can be used for a specific service, or (c) coordination may be required such that use between different services is possible.

Apparatus licenses and unlicensed spectrum

In contrast, apparatus licenses are usually issued by direct assignment, on a first-come, first-served basis. Unlike individual spectrum licenses, apparatus licenses generally use spectrum in less-demanded bands. While some coordination may be required, these licenses usually do not carry the same risk of harmful interference as other services. For example, fixed point-to-point links are highly directional and focused in a concentrated geographic area. The risk of interference from the fixed point-to-point service can be mitigated by maintaining a certain distance from other transmitters or receivers and putting in place certain power limits for services operating in the same band (as modelled in Edwin et. al 2018). Unlicensed spectrum does not require an official license for a device to operate, although registration of such device may be required before its use is authorized, which can be submitted at any time.

Trends in new spectrum licensing

While the method of awarding apparatus spectrum and allowing unlicensed spectrum use has been largely constant, individual spectrum licenses have shown some changes in recent years. There have been several mobile spectrum awards that illuminate new trends in new spectrum licensing, especially as regulators gear up for the deployment of 5G networks.

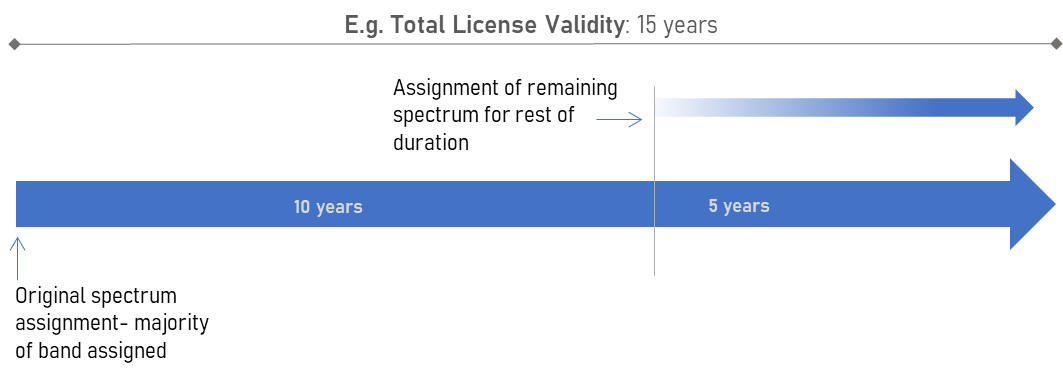

Short-term assignments of unused spectrum

Given the political impetus to promote mobile networks generally, and 5G in recent years, some countries have made unused spectrum in IMT bands available on a shorter-term basis. In Germany and the Slovak Republic, regulators decided to assign the unused spectrum, left unassigned in prior procedures, on a shorter-term basis to align with the existing license terms of the prior assignment, as shown in the example below (New Zealand, MBIE 2019; Slovak Republic, RU 2020).

In Germany, the Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA) is extending usage rights in the 800 MHz, 1 800 MHz, and 2 600 MHz frequency band to align expiry dates with other usage rights and in an effort to avoid regulation-induced spectrum scarcity. This extension also serves as a mechanism for the regulator to implement new coverage obligations, and BNetzA is requiring mobile operators who are granted extensions to meet a series of minimum speed targets in rural communities, roads, and other specified surface areas (BNetzA 2024). The Slovak Republic’s conducted a multiband auction that included 700 MHz spectrum, valid until 2040 and unassigned spectrum in the 900 MHz and 1 800 MHz band, valid until 2025. This simultaneously encouraged the efficient use of spectrum, provides access to in-demand spectrum, and avoids potential delays in network deployment. However, longer-term licenses are still preferable, as they provide more regulatory certainty for operators to invest in new infrastructure and deploy upgrades to their networks.

Trends in license terms

Longer license terms

Many regulators are adopting longer license terms for mobile spectrum, which gives greater regulatory certainty to operators and encourages network investment.

| The preferred approach in the United Kingdom is to issue a license for an indefinite validity, with an initial period, after which time Ofcom will be able to revoke the spectrum under specific spectrum management reasons with notice to the licensee (UK, Ofcom 2005). |

| The EU’s Electronic Communications Code directs member states to offer spectrum rights for at least 20 years (Directive (EU) 2018/1972). Some have interpreted the Code by assigning licenses with a 15-year term with the possibility of a five-year renewal. |

| With the passage of its new ICT Modernization Act, Colombia extended license terms from 10 to 20 years, with the possibility of a renewal of up to 20 years (Law No. 1978 of 25 July 2019, Art. 12). |

| New amendments to Brazil’s telecommunications law allow spectrum licenses to be renewed for up to 20 years and indefinitely, subject to rules to be defined by ANATEL (Law No. 13.879 of 3 October 2019, Art. 167). |

Fulfilling policy objectives

Countries have been increasingly incorporating terms to fulfil other policy objectives in their award of spectrum. Requiring winning bidders to meet certain coverage, deployment, or quality of service metrics is increasingly common in spectrum awards, especially when there is a policy impetus to close the digital divide or deploy 5G networks. Many regulators also include clauses stipulating the date by which the spectrum must be used to uphold the regulatory mandate to promote the efficient use of spectrum. Finally, some regulators take measures to promote market competition by setting aside certain spectrum blocks for new entrants or smaller players, adding requirements to license terms for winning bidders to provide wholesale access to competitors or require national roaming, or establishing spectrum caps in auctions that limit the amount of spectrum one bidder may obtain.

| Germany’s five-year extension of usage rights in the 800 MHz, 1 800 MHz, and 2 600 MHz bands establishes several obligations focused on expanding coverage for rural areas, as well as requirements to promote competition (BNetZa 2024). |

| Albania’s recent 3.5 GHz auction guidelines outline coverage obligations related to population-level service coverage and require operators to begin using licensed spectrum no later than six months following authorization (AKEP 2024) |

| Hong Kong, China’s proposed plan to re-assigning spectrum in the 2 600 MHz band includes spectrum caps to ensure competition and coverage obligations that mandate 90% nationwide coverage within five years of assignment (CEDB 2024) |

| Canada’s 3 800 MHz band auction established a 100 MHz spectrum cap on operators to reserve spectrum for smaller competitors and lower prices for consumers. The licenses also carry “use or lose” deployment obligations to ensure timely rollout, particularly in rural and remote regions (ISED 2023) |

These same considerations have also come into play in direct assignments of mobile spectrum, both when deciding on the award of spectrum and in the terms of the license itself. For example, Singapore’s 5G assignment contained multiple obligations to promote policy objectives.

Singapore

|

When adding obligations to license terms, regulators should monitor licensees’ progress towards meeting obligations and enforce non-compliance. In the absence of planned monitoring and enforcement, license obligations may not be fulfilled. The German Bundesnetzagentur continued to report on the progress that each operator made towards reaching the coverage and speed targets set in its 2015 multi-band auction of spectrum (Germany, BNetzA 2020). In the United Kingdom, the Office of Communications (Ofcom) updated the methodology it uses to measure compliance with 2020 coverage obligations of 900 MHz and 1 800 MHz band licensees, which combines reports from operators’ models and on-the-ground verification (UK, Ofcom 2024). In France, the regulator monitors operators’ progress to meeting specific coverage and quality commitments from a 2018 multiband auction via a quarterly dashboard (France, Arcep 2024). They also monitor national mobile coverage more broadly through its interactive map (https://www.monreseaumobile.fr/).

Key findings

Overview of national spectrum licensing

|

References

Albania. Electronic and Postal Communications Authority (AKEP). 2024. “Granting usage rights in the 3400-3800 MHz frequency band”. https://akep.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Dokumenti-i-tenderit-3400-3800-MHz.pdf.

Belgium. Belgian Institute for Postal services and Telecommunications (IBPT/BIPT). 2020. “Consultation of the BIPT Council of 23 March 2020 regarding the draft decisions concerning the granting of provisional rights of use in the band 3600-3800 MHz”. https://www.ibpt.be/file/cc73d96153bbd5448a56f19d925d05b1379c7f21/24c43e5030619d9b3f355f3df55324abbb327093/Consultation_droits_utilisations_provisoires_5G.pdf.

Brazil. ANATEL. 2020. Act No. 2221, of April 20, 2020. https://www.anatel.gov.br/legislacao/atos-de-certificacao-de-produtos/2020/1404-ato-2221#figura2.

Canada. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED). 2023. “3800 MHz auction – Process and results.” https://www.canada.ca/en/innovation-science-economic-development/news/2023/11/3800-mhz-auction–process-and-results.html.

Czech Republic. Czech Telecommunications Office (CTU). 2020. “Invitation to tender for the award of rights to use radio frequencies for the provision of electronic communications networks in the 700 MHz and 3 440 – 3 600 MHz frequency bands”. https://www.ctu.cz/vyzva-k-uplatneni-pripominek-k-navrhu-textu-vyhlaseni-vyberoveho-rizeni-za-ucelem-udeleni-prav-k-7.

Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 establishing the European Electronic Communications Code. European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L1972&from=EN.

Edwin, E., Tettey Kwabena, D. and Jo, H. 2018. Methods to Evaluate and Mitigate the Interference from Maritime ESIM to Other Services in 27.5-29.5 GHz Band. [Conference paper] Pp. 1058-1063. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8539656.

European Commission (EC). CE marking. [online]. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/ce-marking_en.

European Space Agency (ESA). 2013. Satellite frequency bands. [online]. https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2013/11/Satellite_frequency_bands.

France. Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques, des postes et de la distribution de la presse (Arcep). 2019. 5G: 3.4-3.8 GHz band frequency awards procedure: Arcep invites all players wanting to participate to submit a bid package. [Press release]. December 31. https://en.arcep.fr/news/press-releases/p/n/5g-10.html.

France. Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques, des postes et de la distribution de la presse (Arcep). 2024. The New Deal Mobile Dashboard. [Online]. https://www.arcep.fr/cartes-et-donnees/new-deal-mobile.html#Indoor.

Germany. Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA). 2024. Consultation on extending mobile spectrum usage rights. https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2024/20240513_PKE.html.

Germany. Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA). 2020. Supply requirement from the auction 2015/project 2016. https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/DE/Sachgebiete/Telekommunikation/Unternehmen_Institutionen/Breitband/MobilesBreitband/MobilesBreitband-node.html.

Germany. Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA). 2019. Frequency auction 2019. https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/DE/Sachgebiete/Telekommunikation/Unternehmen_Institutionen/Breitband/MobilesBreitband/Frequenzauktion/2019/Auktion2019.html?nn=268128

Hong Kong, China. Commerce and Economic Development Bureau (CEDB). 2024. “Arrangements for the Frequency Spectrum in the 2.5/2.6 GHz Band upon Expiry of the Existing Assignments for the Provision of Public Mobile Services and the Related Spectrum Utilisation Fee”. https://www.cedb.gov.hk/assets/resources/cedb/consultations-and-publications/cp20240919_e.pdf.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2012. Recommendation ITU-R SM.1047 “National spectrum management” http://www.itu.int/rec/R-REC-SM.1047.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Telecommunication Development Bureau, 2022. DataHub. Geneva, Switzerland: ITU. https://datahub.itu.int/data/?i=100057&s=12593&v=chart.

Law No. 1978 of 25 July 2019. [Ley No. 1978 del 25 julio 2019]. Colombia. https://dapre.presidencia.gov.co/normativa/normativa/LEY%201978%20DEL%2025%20DE%20JULIO%20DE%202019.pdf.

Law No. 13.879 of 3 October 2019. [Lei No. 13.879, de 3 de Outubro de 2019]. Brazil. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2019/lei/L13879.htm.

New Zealand. Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment. 2019. Early Access to 5G radio spectrum. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/10370-early-access-to-5g-radio-spectrum-proactiverelease-pdf.

Singapore. Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA). 2019. “Ahead of the curve: Singapore’s Approach to 5G” [Press Release]. October 17. https://www.imda.gov.sg/-/media/Imda/Files/About/Media-Releases/2019/Annex-A—5G-Policy-and-Use-Cases.pdf.

Slovak Republic. Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications and Postal Services (RU). 2020. Call for Tenders for Granting Individual Licenses for the Use of Frequencies. https://www.teleoff.gov.sk/data/files/49605_call-for-tender.pdf.

United Kingdom. Office of Communications (Ofcom). 2024. Shared Rural Network Coverage Obligations. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/siteassets/resources/documents/spectrum/spectrum-information/mobile-coverage-obligation/shared-rural-network-coverage-obligations.pdf?v=379965.

United Kingdom (UK). Office of Communications (Ofcom). 2005. “Spectrum Framework review: Implementation Plan – Interim Statement”. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/38162/statement.pdf.

United States (USA). Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Equipment Authorization – RF Device. [Online.] https://www.fcc.gov/oet/ea/rfdevice. (a)

United States (USA). Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Logos of the FCC. [Online.] https://www.fcc.gov/general/logos-fcc. (b)

Last updated on: 28.04.2025