Overview of national spectrum licensing

06.10.2020

Source: ESA 2013.

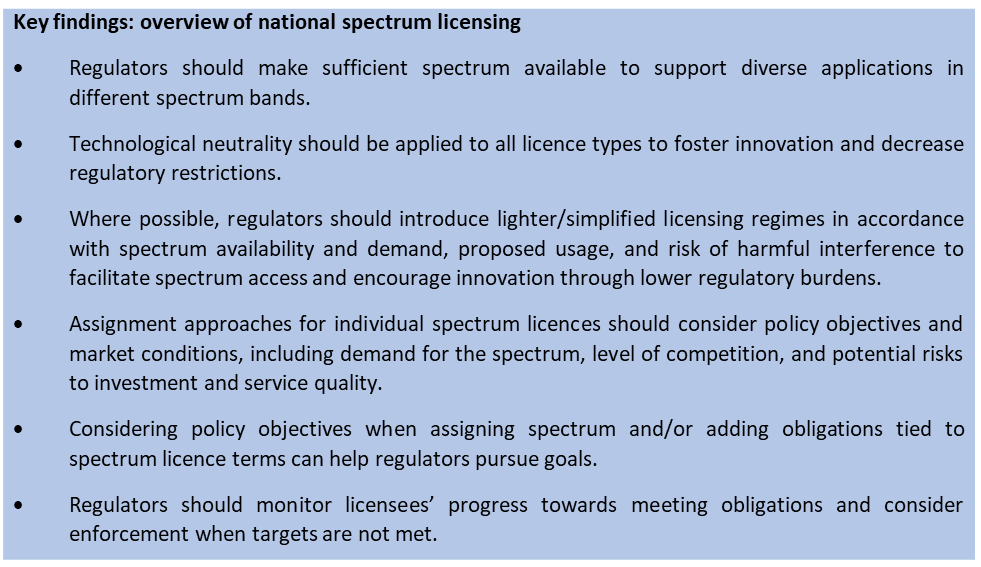

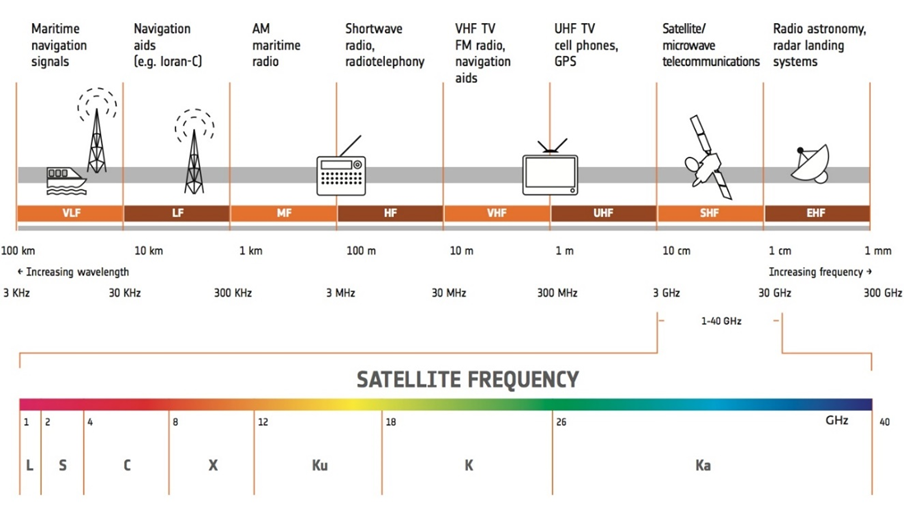

As a limited natural recourse, national administrations manage and assign the use of spectrum. In order to support the wide variety of different telecommunication services, as well as to mitigate possible harmful interference, regulators issue national tables of frequency allocations and establish licensing frameworks that govern how spectrum will be awarded in the country. Regulators also intervene to mitigate disputes in cases of harmful interference along national borders. This process includes working with neighbouring countries on cross-border frequency coordination, recording frequency assignments in the Master International Frequency Register (MIFR) in accordance with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations (RR), as well as possible regional agreements (e.g. the Eastern Caribbean Telecommunications Authority (ECTEL), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Asia Pacific Telecommunity (APT), Arab Spectrum Management Group (ASMG), African Telecommunications Union (ATU), European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT), Inter-American Telecommunication Commission (CITEL), Regional Commonwealth in the Field of Communications (RCC), and so on). Mindful that there are competing demands for spectrum, the regulator’s key role is to make spectrum available across different services which, among others, includes meeting the evolving market demands for expansion of connectivity and access to new applications, taking into account the decisions made at the international and regional levels.

Types of spectrum licences

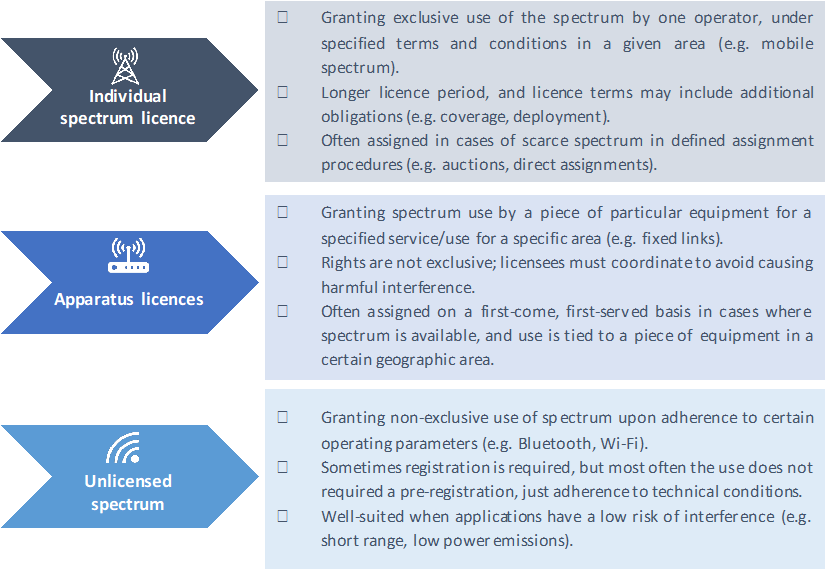

Regulators decide on the licensing mechanism to apply to spectrum by considering a band’s availability, proposed usage, and risk of harmful interference. Generally, spectrum is authorized through one of the following mechanisms:

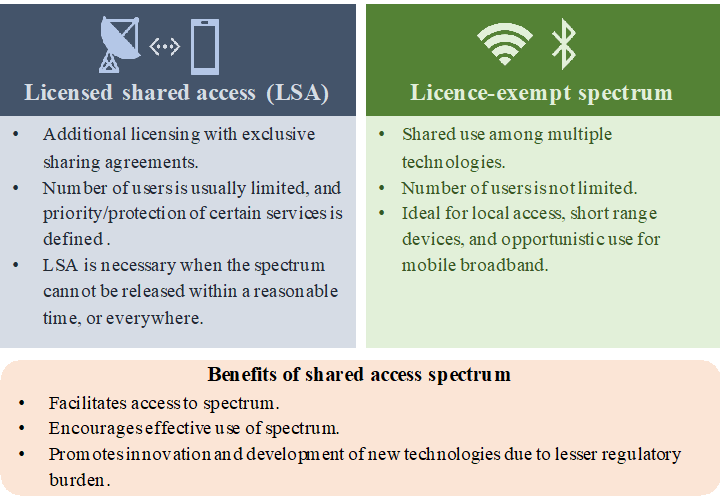

Individual spectrum, and apparatus licences could also fall under a shared access framework, as part of either an unlicensed or licensed regime. In both cases, use is shared with other types of services or users in the band under requirements of non-interference.

An overarching principle that should be applied to all licence types is the concept of technological neutrality. Allowing spectrum to be used by any technology permits operators to evolve as technology and the market advances and to continue to use spectrum efficiently to meet customer demand. This has been widely accepted among regulators worldwide. Roughly three-quarters of countries have introduced the concept of technology neutrality in all spectrum licences and almost 90 per cent had incorporated neutrality in all or some licences (ITU 2019).

Mechanisms for spectrum award

Individual spectrum licences

Individual spectrum licences are usually assigned through an administrative assignment or beauty contest approach, an auction approach, or a hybrid approach.

- Administrative assignment: Regulators assign spectrum to the candidates that best meet specified criteria.

- Auction: Whichever operator places the highest bid for a spectrum block wins the spectrum, although the auction design may include other criteria. Different auction designs include simultaneous multiple round ascending, clock, combinatorial clock, or sealed bid auctions.

- Hybrid approach: A hybrid approach blends auction and administrative assignments. For example, a regulator may select a shortlist of bidders based on administrative criteria and then hold an auction to assign spectrum among the shortlisted candidates.

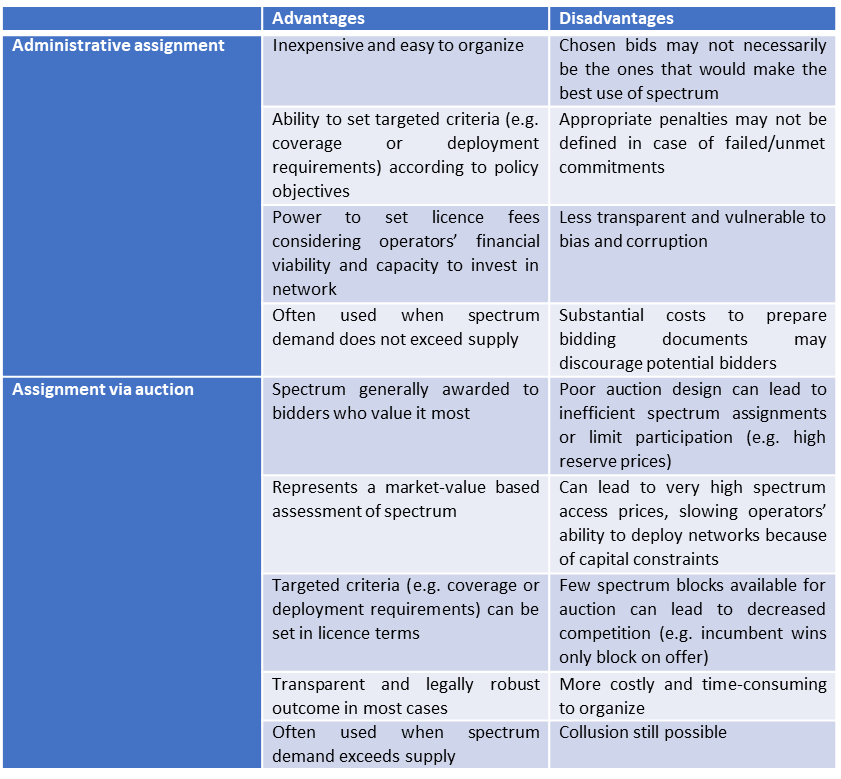

Spectrum for mobile services are more commonly awarded through auctions, although there are examples of both direct assignment and hybrid approaches. Both administrative and auction approaches to spectrum licensing have advantages and disadvantages (see table below). The best assignment approach will depend on the regulator’s policy objectives and the market conditions, including demand for the spectrum, level of competition, and the potential risks to investment and quality of service. Some regulators include aspects of both approaches to balance the risks with the benefits of each.

Comparison of spectrum assignment approaches for individual spectrum licences

Regulators usually issue calls for tenders or proposals for individual spectrum licences, as opposed to awarding spectrum on a rolling basis. This is because the frequency bands may have existing users and spectrum is not available until existing licences expire, the spectrum may need to be reconfigured before it can be used for a specific service, or coordination may be required such that use between different services is possible.

Apparatus licences and unlicensed spectrum

In contrast, apparatus licences are usually issued by direct assignment, on a first-come, first-served basis. Unlike individual spectrum licences, apparatus licences generally use spectrum in less-demanded bands. While some coordination may be required, these licences usually do not carry the same risk of harmful interference with other services. For example, fixed point-to-point links are highly directional and focused in a concentrated geographic area. The risk of interference from the fixed point-to-point service can be mitigated by maintaining a certain distance from other transmitters or receivers and putting in place certain power limits for services operating in the same band (as modelled in Edwin and others 2018). Unlicensed spectrum does not require an official licence, nevertheless, equipment must comply with specific technical conditions to ensure sharing and compatibility with other services. Registration may be required before use is authorized, which can be submitted at any time.

Other examples in spectrum licensing

While the method of awarding apparatus spectrum and allowing unlicensed spectrum use has been largely constant, individual spectrum licences have shown some changes in recent years. There have been several mobile spectrum awards that illuminate new trends in new spectrum licensing, especially as regulators gear up for the deployment of 5G networks.

Short-term assignments of unused spectrum

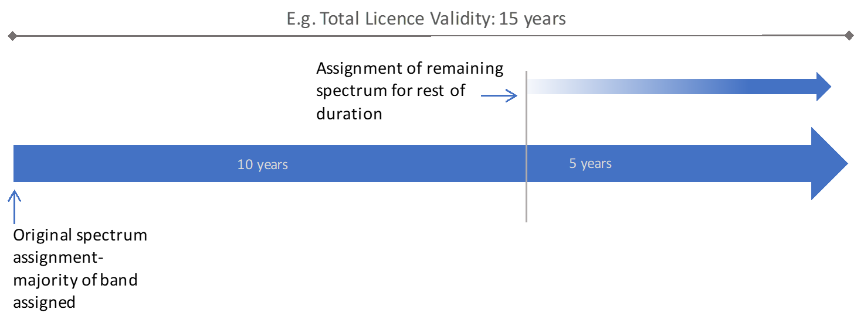

Given the political impetus to promote mobile networks generally, and 5G in recent years, some countries have made unused spectrum in IMT bands available on a shorter-term basis. In New Zealand and the Slovak Republic, regulators decided to assign the unused spectrum, left unassigned in prior procedures, on a shorter-term basis to align with the existing licence terms of the prior assignment, as illustrated below (MBIE 2019; RU 2020).

In Belgium, the Belgian Institute for Postal Services and Telecommunications (BIPT) has proposed to issue 5G spectrum temporarily to avoid 5G deployment delays because of political negotiations in assigning the spectrum on a longer-term basis. The Slovak Republic’s multiband auction include 700 MHz spectrum, valid until 2040 and unassigned spectrum in the 900 MHz and 1800 MHz band, valid until 2025. This simultaneously encourages the efficient use of spectrum, provides access to in-demand spectrum, and avoids potential delays in network deployment. However, longer-term licences are still preferable as they provide more regulatory certainty for operators to invest in new infrastructure and deploy upgrades to their networks.

Trends in licence terms

Longer licence terms

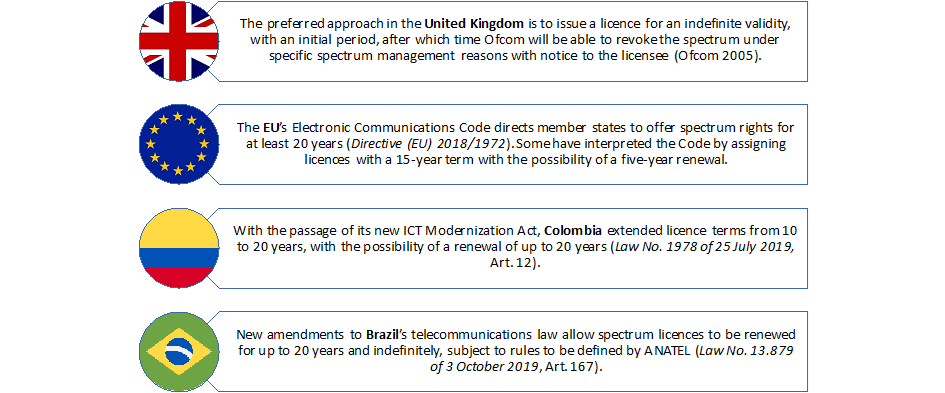

Many regulators are adopting longer licence terms for mobile spectrum, which gives greater regulatory certainty to operators and encourages network investment.

Fulfilling policy objectives

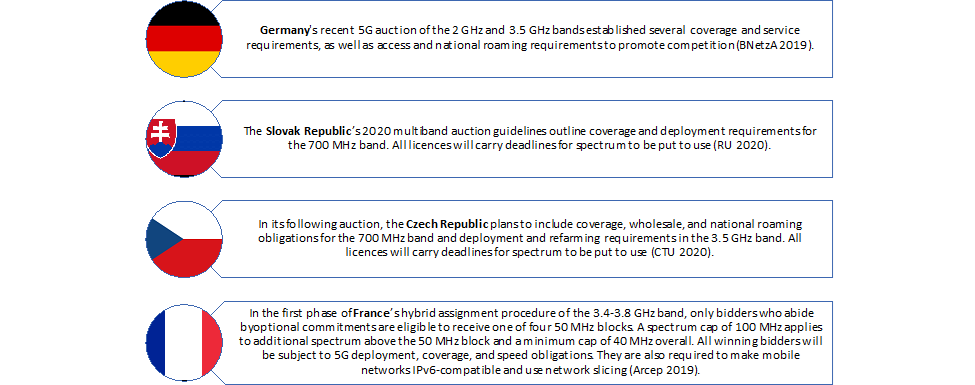

Countries have been increasingly incorporating terms to fulfil other policy objectives in their award of spectrum. Requiring winning bidders to meet certain coverage, deployment, or quality of service metrics is increasingly common in spectrum awards, especially when there is a policy impetus to close the digital divide or deploy 5G networks. Many regulators also include clauses stipulating the date by which the spectrum must be used to uphold the regulatory mandate to promote the efficient use of spectrum. Finally, some regulators take measures to promote market competition by setting aside certain spectrum blocks for new entrants or smaller players, adding requirements to licence terms for winning bidders to provide wholesale access to competitors or require national roaming, or establishing spectrum caps in auctions that limit the amount of spectrum one bidder may obtain.

These same considerations have also come into play in direct assignments of mobile spectrum, both when deciding on the award of spectrum and in the terms of the licence itself. For example, Singapore’s 5G assignment contains multiple obligations to promote policy objectives.

When adding obligations to licence terms, regulators should monitor licensees’ progress towards meeting obligations and enforce non-compliance. In the absence of planned monitoring and enforcement, licence obligations may not be fulfilled. The German Bundesnetzagentur recently reported on the progress that each operator has made towards reaching the coverage and speed targets set in its 2015 multiband auction of spectrum. In the United Kingdom, the Office of Communications (Ofcom) published the methodology it will use to measure compliance with 2020 coverage obligations of 900 MHz and 1 800 MHz band licensees, which will combine reports from operators’ models and on-the-ground verification (Ofcom 2020). In France, the regulator monitors operators’ progress to meeting specific coverage and quality commitments from a 2018 multiband auction via a quarterly dashboard. They also monitor national mobile coverage more broadly through its interactive map.

Equipment type approval

A foundational component of any regulator’s licensing framework is equipment type approval, or homologation. This process ensures that any device that will use spectrum adheres to agreed technical standards, which the regulator assumes will be upheld when licensing the band. Making sure a piece of equipment is operating according to technical standards is important for spectrum use across all bands, but especially so in cases where different applications are using the same spectrum band, like in shared access bands, and in case of the use of licence-exempt bands.

References

Arcep (Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques, des postes et de la distribution de la presse). 2019. “5G: 3.4-3.8 GHz Band Frequency Awards Procedure: Arcep Invites all Players Wanting to Participate to Submit a Bid Package.” Press release. December 31, 2019. https://en.arcep.fr/news/press-releases/p/n/5g-10.html.

BIPT (Belgian Institute for Postal services and Telecommunications). 2020. Consultation of the BIPT Council of 23 March 2020 Regarding the Draft Decisions Concerning the Granting of Provisional Rights of Use in the Band 3600-3800 MHz. https://www.ibpt.be/file/cc73d96153bbd5448a56f19d925d05b1379c7f21/24c43e5030619d9b3f355f3df55324abbb327093/Consultation_droits_utilisations_provisoires_5G.pdf.

BNetzA (Bundesnetzagentur). 2019. Frequency Auction 2019. https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/DE/Sachgebiete/Telekommunikation/Unternehmen_Institutionen/Breitband/MobilesBreitband/Frequenzauktion/2019/Auktion2019.html?nn=268128.

CTU (Czech Telecommunications Office). 2020. Invitation to Tender for the Award of Rights to Use Radio Frequencies for the Provision of Electronic Communications Networks in the 700 MHz and 3 440-3 600 MHz Frequency Bands. https://www.ctu.cz/vyzva-k-uplatneni-pripominek-k-navrhu-textu-vyhlaseni-vyberoveho-rizeni-za-ucelem-udeleni-prav-k-7..

Edwin, E., D. Tettey Kwabena and H. Jo. 2018. “Methods to Evaluate and Mitigate the Interference from Maritime ESIM to Other Services in 27.5-29.5 GHz Band.” Paper presented at the 2018 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8539656.

IMDA (Infocomm Media Development Authority). 2019. “Ahead of the Curve: Singapore’s Approach to 5G.” Press Release. October 17, 2019. https://www.imda.gov.sg/-/media/Imda/Files/About/Media-Releases/2019/Annex-A—5G-Policy-and-Use-Cases.pdf.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2019. World Telecommunication/ICT Regulatory Survey. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Regulatory-Market/Pages/RegulatorySurvey.aspx.

MBIE (Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment). 2019. Early Access to 5G Radio Spectrum. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/10370-early-access-to-5g-radio-spectrum-proactiverelease-pdf.

Ofcom (Office of Communications). 2020. 2020 Coverage Obligations: Notice of Compliance Verification Methodology. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/192919/notice-of-compliance-verification-methodology.pdf.

Ofcom (Office of Communications). 2005. Spectrum Framework Review: Implementation Plan: Interim Statement. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/38162/statement.pdf.

RU (Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications and Postal Services). 2020. Call for Tenders for Granting Individual Licenses for the Use of Frequencies. https://www.teleoff.gov.sk/data/files/49605_call-for-tender.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022