Guide to Meaningful Public Consultations: Collaborative Regulation from Foundations to Sustainable Practices

29.08.2025About this Guide

This Guide was jointly developed by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and Ofcom, the UK’s independent communications regulator.

The Guide is a new tool in the portfolio of tools for national regulators and regulatory associations to support evidence-based decision-making. It provides practical guidance and a blueprint for effectively engaging and conducting regulatory consultations with stakeholders from government, private sector, and civil society and enhancing the outcomes of stakeholder involvement in policy and decision-making processes.

Using a blended approach, the guide draws from insights from 13 interviews with regulators across all regions, various resources on good regulatory practices and experience across the globe. The ITU’s widely recognised expertise in best practices in ICT and digital regulation as the UN specialised agency for telecommunication/ICTs and Ofcom’s decades of national experience enriched this document.

Regulators introducing or expanding public consultation practices, whether into new fields or to revisit core governance principles, have something to gain from both this guide and from broader public engagement.

Introduction

Regulators today recognize the value of sustained public consultations with stakeholders and their important role in making decisions more transparent and evidence-based. Policymakers and regulators in the telecommunications/ICT sector who prioritize public engagement in the regulatory process achieve more effective outcomes and long-term market confidence.

Good, sustainable digital policies and regulation are not designed in a silo. Established regulatory good practices recommend the systematic use of public consultations in regulatory decision-making. The Best Practice Guidelines of the Global Symposium for Regulators and the G5 Benchmark, which assesses the level of national digital governance, recognize meaningful public engagement as a pillar of good governance – a principle also supported by other international organisations (OECD, 2022).

The regulatory process is becoming increasingly open and collaborative. Today, regulators are more responsive and engaged with their stakeholders, adopting evidence-based approaches and considering innovative, out-of-the-box regulatory solutions. Examples include regulatory sandboxes, which allow businesses to test emerging technologies or pilot innovative services as regulators fine tune the appropriate regulations to support further investment and innovation.

At the same time, this evolving regulatory practice must adapt to the rapid pace of technology innovation. Particularly as policymakers and regulators take on the regulatory aspects of digital transformation, new stakeholders enter the picture, and the scope of regulatory impact assessments broaden. Policymakers and regulators, in some particularly innovative sectors, face a clean slate for new regulatory approaches: the opportunity for co-regulation and public engagement is even greater in these settings.

This guide highlights the benefits of public consultations in regulatory decision-making, demonstrating their value in enhancing transparency, accountability and market confidence. It also offers examples of good practice to illustrate not just why public consultations matter but how they can be done.

What is a public consultation, and why is it important?

Public consultations are one of the oldest and most used instruments used by governments and regulators to engage with market stakeholders. Versatile and scalable, consultations take many forms and can be used across traditional and emerging policy areas.

Enquiries, hearings, information and awareness campaigns and roadshows – consultations come in multiple shapes and forms. In the fast-paced, digital environment, consultations provide evidence and stakeholder feedback to support policymakers to make the effective, trusted decisions at the right time and mindful of their short and longer-term impact on the economy, society, and government.

| Defining a public consultationVarious definitions exist, most of them however are fairly similar.

Public consultations:

The objective of public consultations may vary, ranging from

In this Guide, public consultations are defined as a process or event for gathering stakeholder input (including from various parts of government, other public bodies, private sector, civil society and international organisations) to 1) define the scope of policy or regulatory interventions, 2) collect information, views and ideas to inform regulatory decisions, policy formulation or implementation strategies and/or 3) shape or refine legal, policy, or regulatory instruments. Policy and regulation being closely intertwined, the following analysis and guidance can apply to both. |

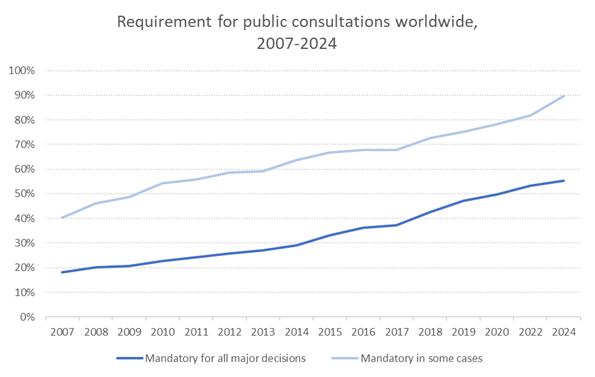

Back in 2007, 35 countries (or 18 per cent of countries worldwide) had already made them mandatory before all major regulatory decisions for the telecommunication/ICT sector. Since then, consultations have been gaining momentum across regions and entering all stages of the policy cycle for both telecommunication and digital markets issues.

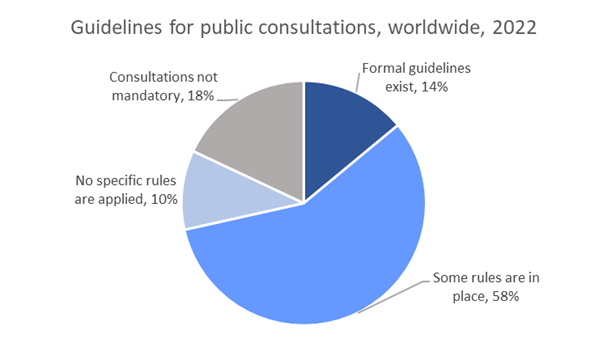

Although 82 per cent of countries worldwide required regulators to apply them in 2022 (see figure below, right), practices across countries significantly vary in how they are conducted, how often they occur, and how they are integrated into their outcomes in policies and regulatory decisions. ICT regulators have different regulatory requirements and apply some of the foundational principles of public consultations differently, resulting in a mixed practice. While ICT regulators in the majority of countries, or 53 per cent, are mandated to carry out public consultations for all major regulatory decisions, consultations are discretionary and only applied for some decisions in 29 per cent of countries[1]. Even when countries require consultations ahead of all major decisions, the same requirement may be differently applied across countries and government institutions.

Global trends in public consultation practice

Source: ITU

Although public consultations are mandatory for all major decisions of ICT regulators in most countries in 2024, only one in seven countries had formal guidelines to ensure they are effectively used for gathering stakeholder feedback. In some 60 per cent of countries, however, these guidelines either do not exist or are incomplete, making the consultation process less structured and predictable. Even where some guidance is available, inconsistent application can lead to uneven practices in conducting consultations and incorporating feedback into decision-making, reducing their overall effectiveness.

Global trends in public consultation practice

Source: ITU

GOALS

The various stakeholders have distinct motivations and opportunities in the consultation process; they all contribute, however, towards enhanced policy- and decision-making and more positive policy outcomes.

- For governments and public bodies such as regulators: ensure policy direction and individual regulatory policies are informed by public interest and attend to the most important and pressing issues of society and the economy. It is a mechanism to expand policymakers’ horizons and to explore emerging issues and areas in which public bodies might have more limited expertise.

- For telecom/ICT service providers: feed into the decision-making process with their views and raise the visibility of their challenges and expectations from the new policy.

- For other digital services providers: provide broader context to the policy and its potential interplay with other policies, trends, or markets.

- For consumers and civil society: advocate for consumers’ interest and perspectives within the analysis of a policy or regulatory issue.

| From global best practices‘Policy and regulation should be consultation and collaboration based. In the same way digital cuts across economic sectors, markets and geographies, regulatory decision making should include the expectations, ideas and expertise of all market stakeholders, market players, academia, civil society, consumer associations, data scientists, end-users, and relevant government agencies from different sectors.’ |

While not a guaranteed solution, consultations provide a public space for discussion and bargaining. In turn, this can increase the likelihood of viable solutions and sustainable compromise.

PRINCIPLES

Public consultations are built on foundational principles underpinning their objectives, process and outcomes. While there may be additional principles relevant to individual consultations or specific national contexts, the following guiding principles emerged as established good practices and insights from the regulators interviewed, as an essential part for enabling meaningful outcomes in their consultation processes.

- Due diligence, transparency, and accountability

Public consultations play an important role in effective governance by promoting transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making. They serve as a mechanism for ensuring that decisions reflect market realities for service providers and for consumers alike; provide proportional interventions where justified; and respond to immediate problems while providing long-term, sustainable solutions. - Participation, representation, and inclusion of relevant constituencies

Consultations provide an opportunity to communicate on policy priorities and projects beyond the public sector and in turn, allow feedback of parties affected directly or indirectly by a new policy or regulation. Typically, actual or potential market actors are the most active in the process. When broader citizen groups are either targeted by or beneficiaries of a new policy, consultations also allow policymakers to document and evidence the potential public benefit of a policy decision. - Common good

Decisions forged through consultation are more likely to be balanced and made in consideration of the interests of all stakeholders and serving broader development or growth objectives. Consultations also allow aligning stakeholder interests and objectives to high-level policy directions. - Evidence-informed decision-making

Each consultation is an opportunity to collect evidence and test hypotheses on new policy issues and what policy options are available and their pros and cons. This can help policymakers develop and refine a risk-based approach to regulation. Through the consultation process, policymakers can collect a substantial amount of evidence, which then needs to be validated, weighed, and integrated in the policy outcome. - Outcome-based process

Stakeholder engagement can raise important considerations, calling for a refinement or revision of draft policy proposals. Consultations, when done effectively, are positioned at a time in the policy cycle where change is still possible. Inversely, failing to integrate the findings of a public consultation in the outcome jeopardises the process and might reduce the chances for the new policy to be successfully implemented.

| Risk-based approaches to regulationRisk-based approaches to addressing emerging policy and regulatory issues involve prioritising actions based on the assessment of risks and their potential impact. This method allows policymakers and regulators to allocate resources efficiently, focusing on areas with the highest potential for harm or the greatest opportunity for benefit. By systematically evaluating the likelihood and consequences of various risks, decision-makers can develop targeted strategies that address the most significant threats or vulnerabilities while avoiding unnecessary regulation in areas with minimal risk.

For instance, in the realm of digital technology and cybersecurity, a risk-based approach might involve identifying the most critical infrastructure and data assets, assessing their vulnerabilities, and implementing protective measures where the potential impact of breaches is highest. This ensures that limited resources are directed towards safeguarding essential services and sensitive information. Similarly, in connectivity regulations or when applied to decisions having an environmental impact (e.g. location of mobile towers or data centres), this approach could prioritise interventions in regions or sectors where the risk of ecological damage is most acute. Overall, risk-based approaches provide a balanced, evidence-driven framework for addressing complex and dynamic policy challenges, enhancing resilience, and ensuring that regulatory efforts are both effective and proportionate. |

PROS AND CONS

From a regulator’s point of view, public consultations offer important advantages. They:

- Inform upcoming regulatory policies by integrating perspectives of market actors, ecosystem stakeholders and consumers, including under-represented groups affected by decision-making.

- Build trust in the legal and political system and consensus around upcoming policies.

- Provide space to test new ideas, crowdsource solutions and access the expertise of stakeholders (e.g. industry, investors, civil society).

- Improve governance by broadening the base for regulatory policies and adding transparent due process.

It is worth recognising that consultations may also present challenges and have their limitations. They might:

- Extend the policy process, add cost and workload to the administrative decision-making process and the regulator in charge.

- Reveal conflicts of interest between stakeholders and/or with decision makers, which need to be resolved.

- Fail to engage key stakeholders, resulting in bias in decisions.

- Be overridden by political influences, becoming a token of inclusive decision-making as opposed to a genuine driver of better policies.

- Decrease stakeholder engagement if inputs are not reflected within the regulator’s decision-making.

Blueprint for meaningful public consultations

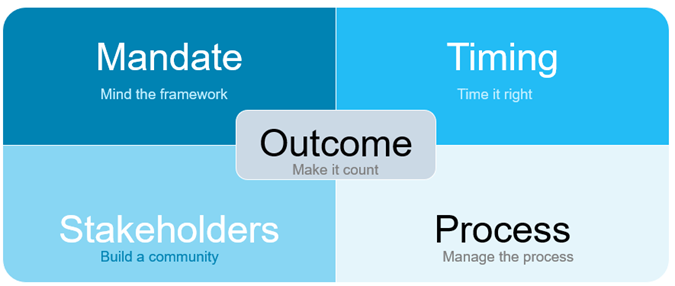

The next sections of this guide offer practical steps and comparative practice for the key pillars of a successful public consultation.

Figure: Pillars of the Blueprint for meaningful public consultations

Source: Guide to Meaningful Public Consultations, ITU and Ofcom (2024)

The Blueprint presented below was designed to support ICT regulators and policymakers looking to improve their public consultation practice to achieve better policy outcomes through structured and inclusive stakeholder engagement. The analysis was informed by global good practices identified by international and regional organisations and by the experience and insights of a dozen ICT regulators.

Each section is paired with hands-on resources to help regulators undertake each step of the process. These resources are not meant as prescriptive tools but more as templates from which regulators can adapt to their need and to their national context.

By the end of this guide, policymakers should be better prepared to conduct a successful public consultation that meets international best practices for inclusive and engaging policy- and rule-making.

PILLAR I: MIND THE FRAMEWORK

Institutional mandates for public consultations are frequently established through legal or policy arrangements. They outline the requirements and procedures for engaging with stakeholders on matters of public interest.

These mandates often specify the scope of consultations, the types of decisions that must be subject to consultation, and the obligations of public bodies, such as regulators, to seek input from the public. Additionally, they may detail the methods for conducting consultations, timelines for engagement, and specific mechanisms for ensuring transparency and accountability throughout the process.

Such mandates serve to institutionalise the practice of public consultation, promote democratic governance, and enhance public trust in decision-making.

In this section…Policymakers will learn about the institutional foundations behind many consultations that several ICT regulators conduct today. It will span legal frameworks, institutional accountability, and common regulatory rules across several different countries. From this, readers can consider what framework(s) apply in their country and would be important to account for before conducting a public consultation. |

Legal frameworks

It is consistent with international best practices for the regulator’s decisions to be subject to a general administrative procedure law. Establishing an administrative procedure framework helps ensure that the regulator abides by a systematic, transparent, and consistent set of procedural rules, including for public consultations as a vehicle for gathering evidence for the regulatory decision-making process, and provides regularity for other stakeholders to understand and anticipate how the consultation process will proceed. Considering country-specific conditions and legal traditions, the administrative procedures law may apply only to the regulator in charge of telecommunications and/or the ICT sector or may be a law applicable to administrative bodies/agencies in general.

Legal mandates for consultations can be found in various instruments:

- In the national Constitution: In some countries, citizens’ participation in government decision-making is fundamental to the functioning of a democratic system of governance as stated in chapter one of the Constitution of Kenya of 2010. Public participation enabled through public consultation is therefore a fundamental constitutional principle.

- In general administrative procedures law: in countries where a unified whole-of-government framework exists, public consultation processes are mandated as part of the standard administrative process and often inscribed in the administrative law, for example in Anguilla, Brazil, Canada, Finland, France, Oman, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.

- In sectoral law: in some countries the requirement to hold public consultations is defined in the ICT sector law, for example the National Information Technology Law of Saudi Arabia, or the legal act establishing the regulatory authority, for example Resolution No 612 (2013) of Anatel Brazil.

- In other regulatory decisions or policies: for example in Egypt, the National Telecom Regulatory Authority (NTRA) launched a Regulatory Frame for Public Consultation, in order to reinforce transparency and create a more effective decision-making mechanism. In Saudi Arabia, two Cabinet Decisions promote the use of this mechanism for public agencies.

- In internal guidelines: some ICT regulators have crafted internal guidelines to structure and inform the public consultation process. Such internal guidelines may be a first step towards the adoption of an official institutional instrument or add additional detail beyond formal, published requirements on the structure of public consultations. Such guidelines exist in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Ofcom, in the United Kingdom, has seven principles for its public consultations.

It is considered good practice to formalise rules for public consultations. This provides stakeholders with predictability and builds trust in a due-process governance framework. However, such formal structures are not the limitation of how public consultations can or should be conducted.

Spotlight on developing organizational guidelines for public consultationsThe steps of the standard process for developing such guidelines are:

|

Rules are nevertheless only useful if they are meaningfully applied to achieve the goals of a public consultation, so countries without formal rules and also regulators looking to expand beyond the legally required minimum can also reap the benefits of a robust consultation process. Using public consultations, even outside of a formal framework, can be an important first step towards codifying the process in legal acts and a useful first experience to inform the specific rules and procedures to be put into place.

Interview insights: IFT, Mexico

|

Common features of consultation guidelines

It is considered good practice that consultation guidelines include core requirements ensuring due process, transparency and accountability as well as meaningful evidence from the consultation as input to the policy or decision-making process.

| Good practice | Risk in the absence of clear rules |

| Clear process for consultations is defined | In its absence, several risks can emerge, impacting the effectiveness, transparency and legitimacy of governance.A lack of clear processes can make it difficult for the public to understand how decisions are made and how their input is considered. It may also lead to policies and regulatory decisions which are less responsive to stakeholder needs and market realities and therefore less effective.

The lack of clear process also makes it more likely for stakeholders to resort to legal challenges to regulatory decisions, thus delaying implementation – in some cases, for several years. The risk for a real or perceived capture reduces trust in government decisions by both industry and consumers, also impacting the international standing of the country regulatory environment. |

| Deadlines are clearly communicated and provide sufficient time to contribute | When deadlines are not defined or they are too short (such as less than 30 days for major decisions), the consultation is unlikely to attract and benefit from the views of a great number of stakeholders.

|

| Diversity and inclusion are key consideration in defining the target stakeholder groups for a consultation and the outreach strategies | In the absence of guidance or rules intended to ensure the diversity of stakeholders targeted or reached by a consultation, the consultation may become self-reinforcing, excluding key stakeholders from the process and failing to reflect the diversity of stakeholder views in the final decision.The views of non-traditional market stakeholders may be pivotal in the discussion on new issues or technologies, but institutional channels may fail to engage them through the conventional means (e.g. announcements on the website of the regulator, the official gazette or formal public hearings. Examples of such stakeholders are regional operators without market footprint in the country, adjacent industries (e.g. digital content producers) or some consumer groups (e.g. persons with disabilities, people with low or no literacy, indigenous, migrant groups, or rural populations).

Failing to include key beneficiaries or stakeholder groups otherwise affected by regulatory decisions can result in policies that are less effective or face significant public opposition. According to the OECD, administrative procedure laws ‘can strengthen the rights of citizens when they are potentially affected by a policy decision (for instance as in Iceland, Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, Poland, Norway). The laws may include prior notice and public hearings where citizens can pose questions and defend their interests. These rights may concern all interested citizens (for instance in Finland), or only those directly affected (for instance in Italy). They may grant the right to objection and appeal after the decision is made but before the decision is implemented (for instance in the Netherlands).’ |

| There is a requirement to publish and respond to stakeholder comments | No obligation to consider/respond to all comments may discourage stakeholders to take part in consultations, failing to inform decision makers of potentially important considerations for their successful implementation.This can defeat the purpose of the consultation and create perceptions among market stakeholders of inefficient governance, disincentivising investment and market innovation. From a consumer standpoint, not ‘listening’ to stakeholder views may result in missing opportunities to enhance and diversify services for consumers and include all as beneficiaries of the decisions at hand. |

| The consultation report specifies if/how stakeholder input was integrated in the final decision and texts | Likewise, a lack of transparency on how stakeholder input was meaningfully considered in the decision-making process can undermine trust in governance structures and regulatory environments. |

| The Guidelines should be publicly accessible to all stakeholders and beneficiaries of regulatory decisions. | While internal guidelines may ensure due-process, transparency and accountability are not guaranteed if the Guidelines are not made public. Keeping them internal crates room, or at least the, perception, for discretionary action. |

| Confidentiality is ensured | On sensitive topics or for certain stakeholders, a guarantee of confidentiality may be a strong incentive to provide open and therefore more useful to the regulator feedback. Stakeholders are more likely to express genuine concerns, share sensitive information, and provide candid opinions without fear of retribution or negative consequences. This is particularly important in situations where stakeholders might be in a position of vulnerability or for some reason would not be inclined to share publicly their views, such as in consultations involving controversial regulatory issues, changes to status quo, asymmetric regulations, or policies affecting marginalised communities.Confidentiality is also essential in consultations involving proprietary or sensitive business information. For instance, when businesses or industry experts are asked to provide input on regulatory changes or economic policies, they may need to share data that is commercially sensitive. Ensuring confidentiality in these cases protects their competitive interests and encourages participation.

Additionally, confidentiality can help protect the personal information of individuals, fostering a safer environment for public engagement and ensuring compliance with data protection laws. Overall, maintaining confidentiality enhances the integrity of the consultation process, leading to more reliable and comprehensive input. |

Institutional responsibility and accountability

The public body in charge to carry out public consultations is usually the one with the decision-making power to adopt the policy or regulation under consideration. In practice, it is often the entity responsible for developing the document that pilots the consultation process or otherwise supports it (e.g., the regulatory authority may engage in a consultation on a policy or their own regulatory decisions).

With regards to how responsibilities over the consultation process are attributed within the regulator, country practices typically show two approaches:

- Executive board members or other leadership positions such as the Director General take ownership and hold the overall responsibility over and is accountable for a consultation process, for example in France, Dominican Republic, Singapore or Brazil.

- Project teams bringing together professionals from various departments and areas of expertise (e.g. legal, technical public affairs, communications) are tasked to carry out the consultation process. This is the case of Canada, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, Bosnia and Herzegovina or Oman[2].

The assignment of responsibility within a regulator and the allocation of sufficient resources (e.g. dedicated staff and budget) can be important for how public consultations are conducted. With high-level engagement, consultations can benefit from resourcing available at those levels and may be supported with greater institutional knowledge across different consultations and constituents. Assigning responsibility to project teams can bring experts closer to the stakeholders engaged in the consultation, but these experts may be less familiar with the procedural steps of a consultation and comparative practice. In either context, clear accountability is critical for ensuring that a consultation is completed and has impact on the policy process.

Organizational guidelines

The legal mandate for public consultations can be general or specific, leaving more or less space to the responsible public body to lead the process and integrate the stakeholder input received in the final decision.

Looking at the global landscape in 2023[3]:

- Public consultations were mandatory in 60 percent of countries worldwide for telecommunication/ICT regulation, although some only carry out consultations on an exceptional or discretionary basis and consistently for all major regulatory decisions.

- In the large majority of these countries (or some 43 percent of all countries), ICT regulators have a legal mandate to carry out public consultations for major regulatory decisions without specific requirements on how to conduct them.

- Less than a fifth of all countries had formal guidelines including core requirements on designing public consultations as a tool to gather feedback from national stakeholders and guide regulatory decision-making.

Cross-sector legal instruments such as public administrative law may establish a baseline for conducting consultations by all public entities. Even when such guidelines exist, it is considered good practice to adopt organisational guidelines based on but tailoring the generic public sector guidance for the regulatory agency’s specific needs and the nature of the consultations they conduct. This helps create predictability for stakeholders in the consultation process, builds trust and legitimacy in the consultation process overall, and preserves institutional memory on the procedural aspects of a public consultation.

Examples of cross-sector consultation frameworks

Examples of ICT regulatory authorities’ guides

|

Regulators commonly use their own guidance or policies to establish a systematic, transparent and consistent set of procedural rules for public consultations. These rules typically detail specific steps in the regulator’s consultation and decision-making process, including: the timeframe for responses; forms and manners for the submission of comments; and evidence and issues of confidentiality, among others. This level of detail can help provide consistency and reduce ‘setup’ costs with each consultation by providing a clear template for future procedural steps.

Common features of consultation guidelinesIt is considered good practice that consultation guidelines include core requirements ensuring due process, transparency, and accountability as well as meaningful evidence from the consultation as input to the policy or decision-making process:

|

PILLAR I: PRACTICAL TIPS FOR SETTING UP A SOUND CONSULTATION FRAMEWORK

How should this guidance be used?

The Step-by-Step Guidance sets out a list of questions, based on and organised according to the five pillars of the Blueprint for meaningful consultations (section 3). Hence, this Guide provides practical hints into the various stages and aspects of public consultations for organisations to consider in a systematic manner and operationalise the Blueprint.

Through a step-by-step approach and guiding questions, this and the similar sections below offer a path to implementing for the first time or enhancing public consultations. It goes without saying that regulators are encouraged to refine, adapt and develop further their approach to ensure it is fit-for-purpose in their context and matches their priorities and aspirations. Regulators should not attempt to follow the steps and apply all questions mechanically because not all practices and considerations may be applicable in their context.

When using the Tool, organizations should consider whether the questions and practices are relevant to their unique policy, regulatory and market environments. Organizations would also need to consider their mandates and the specific goals of the consultations at hand, resource constraints, regulatory requirements and specific use cases. Generally, an organization should consider integrating consultations into broader risk-based approaches to addressing emerging policy and regulatory issues and those with potentially significant impact on markets and consumers. An example of this would be to use a risk-based approach in prioritising action and resources.

| Step | Guiding questions | Decision-making/Action |

| Identify existing legal instruments |

|

|

| Develop organisational guidelines |

|

– Draft and consult on refined guidelines

|

| Adopt/revise and publish guidelines |

|

|

PILLAR II: BUILD A COMMUNITY

When successful, public consultations attract a wide network of diverse stakeholders willing and able to share their views and provide evidence to inform policies and regulatory decisions.

The target stakeholder groups and individual stakeholders for each consultation will depend on the topic at hand, the magnitude of impact of the decision and the resources available to the organisation leading the consultation process.

However, it is important for regulators to maintain relationships with key stakeholders in their regulated markets both within the context of a public consultation and across time to encourage participation and enable stakeholders to engage with confidence and purpose in the consultation process.

Common stakeholders

Regulators hold a unique convening power to bring together different stakeholders within the ICT sector. Within their frequent mandate to promote market competition, regulators have to balance the interests of several stakeholders into a holistic perspective towards long-term sustainability. Regulator stakeholder engagement is a key part of this responsibility and strategically important for regulators in performing their duties.

From our research, three main groups of stakeholders stand out as key counterparts of ICT regulators and policymakers in the public consultation process.

- Public sector bodies

Including ministries, regulatory authorities, national committees or commissions on related or relevant issues (e.g., ICT, digital technologies/digitisation/digital transformation, competition, investment, innovation, environment, finance)

They are natural allies and collectively responsible to engage in developing broad, cross-sectoral policy and its implementation.

Consultations with public sector stakeholders allow to strengthen policy coherence, ensure coordination with entities with close mandates, reduce potential misalignments that can stall implementation, and tap into additional knowledge bases and perspectives to inform the consultation topic.

Local and regional governments and public bodies are often particularly important to include in consultations, as they may have a critical role in the implementation of a regulatory decision. Failing to address their needs and concerns may result in delays and issues for other stakeholders.

| Chapter 10 of the South Africa Communications Act details how ICASA, the independent ICT regulator, and the Competition Commission interact on competition matters within the electronic communications industry. |

- Market actors and private sector

Such as telecom/ICT network operators and service providers, digital platforms, business associations, equipment manufacturers, investors

They are valued for their industry or technical expertise, market potential, experience or influence, and their resources, and the impact that regulation has on their operations is a critical component to evaluating a regulation’s sustainability.

Their views are instrumental to assess the impact of future decisions or policy directions on investment, market dynamics, consumers and ultimately, the achievement of policy goals. What’s more, their buy-in of regulatory policies or the lack thereof can affect the policy’s impact.

Failing to address their needs and concerns may result in enforcement and implementation challenges, shortfalls, and delays. For example, private sector engagement in a consultation can test hypotheses for institutional capacity for compliance, both for the regulator and for business; can equalise informational asymmetries between market actors; and reduce the potential for market actors to later appeal enforcement through judicial review or appeals.

| Regulators commonly cited industry, especially major network operators or service providers, as frequent participants in their consultations. Many regulators, including Indotel in the Dominican Republic, are looking at ways to boost participation from smaller operators and less-active industries whose voices may be valuable in the consultation process. |

Private sector players are key counterparts of regulators in Brazil, Canada, Kenya and examples.

- Consumers and civil society

Including consumer groups, interest groups, academia, communities, and individuals

Consumer associations and community groups can be critical allies for regulators focused on evidencing the potential public benefits of a regulatory decision. Such organisations can provide evidence of consumer harm and frustration with the status quo and the need for regulatory intervention. Community groups can help deepen impact by engaging underserved or underrepresented parts of society within the regulatory process.

Such groups can also bring light to new or emerging regulatory issues, such as the environmental impact of telecommunications and ICTs. As digitalisation takes hold across the world, the environmental sustainability of these systems and services have grown as a concern for consumers.

This constituency of stakeholders may benefit from different or less traditional forms of engagement. Due to limited resourcing and expertise in technical matters, regulators may find multi-channel approaches combining online platforms, townhalls, surveys, and other approaches can be used to address the specific consultation questions to capture consumer concerns and lead to policies that are more representative, equitable, and practical.

To learn more about the various stakeholder outreach strategies, check the Public consultation toolkit below.

| Community groups and representation Including rural populations, women’s groups, indigenous peoples, people with no or low literacy, people with disabilities, and immigrant groups Depending on the consultation topic, some groups of society or geographic regions may be potentially more affected than other of the regulatory decision or policy. Examples of these are network rollout in rural areas, the analogue switch off and elderly groups, and universal access programming and low-income communities.It is best practice to provide populations uniquely affected by such policies or initiatives with the opportunity to share feedback to inform decision-makers of the less generalised and sometimes unintended effects, both positive and negative, and the sentiments of these populations in relation to the topic at hand.

Indigenous peoples play an important role during public consultations in Canada, South Africa and targeting them as a consultation constituency is particularly significant in countries with multi-ethnic societies or where such populations are living in rural and remote areas and facing issues with public representation. Interview insights: In Canada, CRTC ‘Phase II of the review of the state of telecommunications services in Canada’s Far North’ made particular efforts to reach diverse groups – especially rural and Indigenous communities – by offering different means of engagement (e.g., the CRTC Conversations platform), promoting widely and using various methods, and holding the public hearing in an Indigenous cultural centre in Canada’s Far North. The call for comments document was also drafted to be more concise and in plain language. ‘To reach Indigenous communities, a summary document of the consultation was made available in multiple Indigenous languages and the timing of the consultation was deliberately chosen to avoid conflict with inconvenient times of year (e.g., hunting season) for these communities.’ |

Engagement strategies

Regulators and policy makers can employ various strategies for continuing engagement with key stakeholders or stakeholder group so to keep abreast of their needs and concerns. Such strategies require resources (both human and financial) but allow building a deep understanding of the stakeholder environment ahead of and through the consultation process and a better outcome.

On the other hand, engaging with stakeholders on a one-off basis on the occasion of a consultation campaign can also be effective, however the outreach will require a greater effort in a short period of time also removing internal resources from other areas of the consultation process.

- Breadth: inviting multiple or all stakeholder groups to engage with the consultation and aiming to disseminate the information on the process as widely as possible in a generic manner.

- Depth: handpicking key stakeholders and focus on their meaningful engagement with the process while putting less effort into widely publicising and encouraging the participation of all stakeholders and stakeholder groups.

A hybrid approach is also possible whereas the main stakeholders are engaged on an ongoing basis and specific groups potentially affected by a consultation are targeted as part of a campaign.

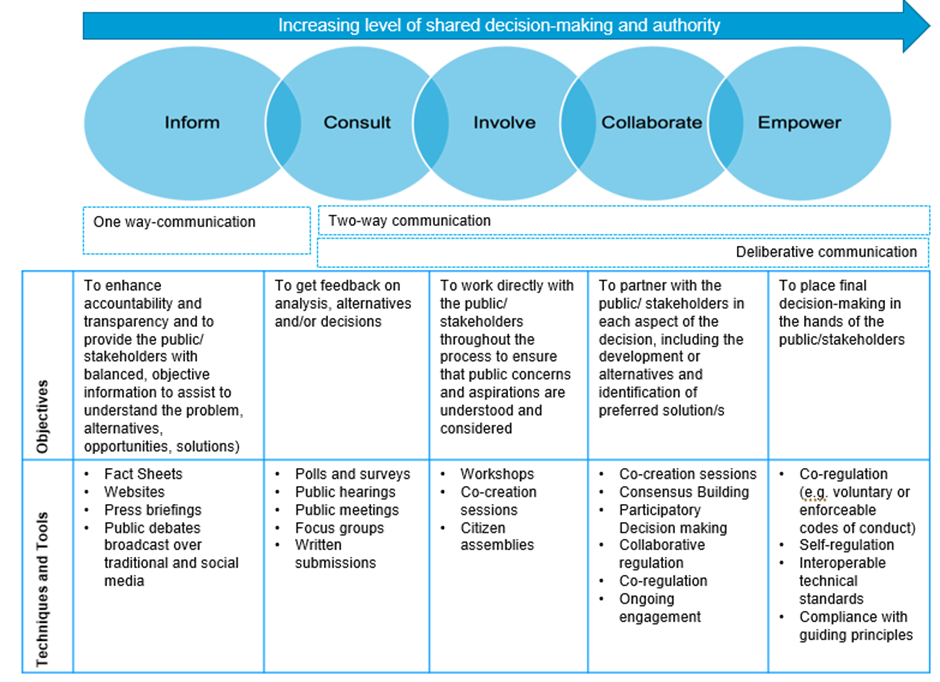

The framework below outlines five levels of shared decision-making achieved through public consultations and the objectives and tools corresponding to each level, indicating increasing levels of power given to stakeholders to influence the policy process.

Public consultation engagement continuum

Source: ITU Policy Acceleration Playbook (unpublished), adapted from IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum.

The framework can assist organisations to decide what type of public participation is desired and what kind of tool or output can derive from that type of participation. It is then up to policymakers and regulators to deploy the tools according to the specific circumstance, ensure their wide dissemination and work through the evidence and feedback received from stakeholders.

Neutrality and convening power of regulators

Regulators, importantly, are typically required to ensure their independence from both private sector interests and political interference in their work. Their neutrality and expert judgement guarantee the fitness for purpose of regulatory policies and pave the way to effective implementation. This feature is a cornerstone to their ability to convene stakeholders and consolidate divergent interests in a holistic approach towards market competition.

In addition to being powerful mechanisms for enhancing representation and informing policies, public consultations are an opportunity for vested interests to contribute to the policy debate. Being mindful of potential or perceived conflicts of interest and drawing a line between lobbying and informing decision-making processes is essential to ensure alignment of the interests of all stakeholders to the overarching policy direction and goals. Regulatory independence supports widespread trust in the decisions it takes to be fair and well-reasoned in consideration of multiple points of view.

Resources for effective stakeholdership

Resources available for the consultation process are a major decision factor in choosing the format, vehicles, and strategies for stakeholder engagement.

Good practices and guidelines for conducting public consultations tend to introduce multiple requirements in terms of the expertise, time, stakeholder relationships and means available to the team in charge. It is important to be realistic when assessing these in order to choose a strategy and build a plan. Laying out an ambitious, complex strategy for a consultation without ensuring adequate resources may quickly prove unrealistic, jeopardising the outcome of the consultation and putting the reputation of the leading organisation at risk.

Resource considerations are particularly topical in the context of organisations in small states or those with small operational teams. In such cases, a simpler, more practical strategy can deliver better results than a resource-intensive plan.

Resource pooling among multiple organisations is a possibility worth exploring and particularly relevant when the consultation topic is of cross-sectoral or cross-disciplinary nature. Experience so far has been limited, however, due to the difficulties of delineating responsibilities and agreeing on collaboration modalities.

PILLAR II: PRACTICAL TIPS FOR BUILDING A COMMUNITY

| Step | Guiding questions | Decision-making/Action |

| Nurture relations with stakeholders and build trust on an ongoing basis | Public consultations must be seen as a key part of the policy process occurring early and with actual influence on the outcome policy

|

|

| Articulate a long-term stakeholder engagement vision |

|

|

| Develop an understanding of the role of stakeholder engagement in the decision-making process |

|

|

| Allocate adequate funding for stakeholder engagement |

|

|

PILLAR III: TIME IT RIGHT

Selecting the optimal moment for stakeholder consultation during the policy process is crucial for ensuring meaningful participation and effective decision-making. Engaging stakeholders at a point where policy options are still open for discussion allows for a diverse range of perspectives to be considered, fostering a more inclusive and representative policy outcome that likely has higher chances for success.

| In this section…The timing of a potential consultation is set against the broader context of the policy thinking cycle and events outside a regulator’s control – like an election – that might affect participation. Consultations are valuable at several points in the policy process, but tailored approaches might be more valuable at certain stages over others. From this section, readers can start to schedule their consultation – how much time it will take, when it will occur, and what major milestones to plan around. |

Engaging with stakeholders can be useful at every stage of the policy process. For example, early consultations can raise awareness about new issues likely to affect consumers, prevent the entrenchment of specific agendas and enable adjustments to be made based on stakeholder feedback, enhancing the legitimacy and acceptance of the policy.

Moreover, regular, timely consultative practices demonstrate a commitment to democratic principles, co-regulation, and transparency in governance, building trust between policymakers and the stakeholders. Ultimately, timely and genuine stakeholder engagement can lead to more innovative solutions and sustainable policies that are better aligned with market needs and expectations of society.

Source: ITU

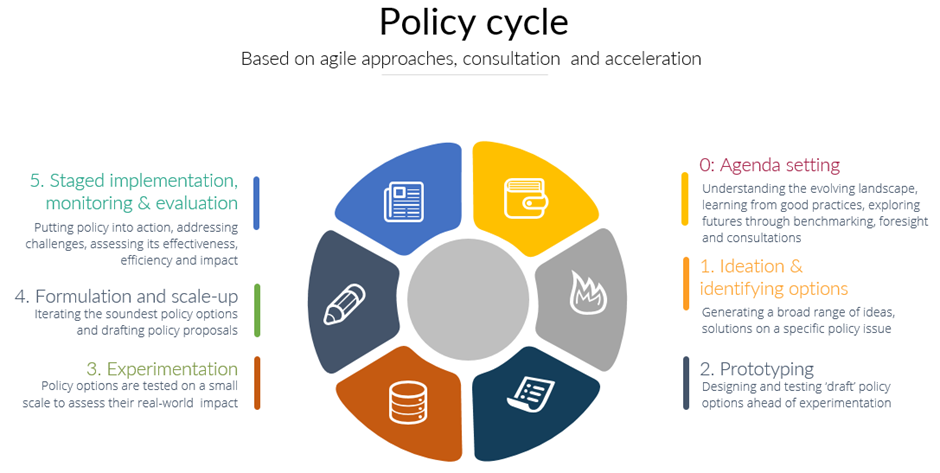

Phases of the policy cycle

Consultations can occur at several stages of the policy cycle. At different stages, different approaches may be more valuable or effective for engaging stakeholders and utilising their expertise. The timing and format of consultations depend on a country’s specific circumstances, the regulator’s preferences and the nature of the consultation topics. For example, earlier and later stages of the policy thinking cycle might benefit from more informal, smaller engagements with stakeholders to encourage more candour in the ideation phase and more detail in the implementation phase while more formal stages are common for key milestones around issuing a draft decision or policy.

Interview insights: IFT, Mexico

|

| Policy cycle phase | Benefits of consultation | Example consultation formats |

| Phase 0: Agenda settingThe inception phase lays the foundation of the policy process, its direction and outcomes. It is focused on identifying priorities and scoping areas for action.

Benchmarking, foresight and consultations at various levels provide the framework for evidence-based policy and decision-making in all staged of the policy process. It looks into the past, present and futures.

|

|

|

| Phase 1: Ideation and Identifying OptionsThe phase involves generating a broad range of ideas and potential solutions to address a specific policy issue.

This phase focuses on creative thinking and exploration, drawing on stakeholder input and expert insights to identify various policy alternatives that can be evaluated in subsequent stages. |

|

|

| Phase 2: PrototypingPrototyping focuses on designing and testing ‘draft’ or preliminary versions of policy options to assess their feasibility, effectiveness and potential impact.

This phase allows policymakers and regulators to experiment with different approaches, gather feedback, and refine solutions before scaling up policies and moving into implementation. |

|

|

| Phase 3: ExperimentationDuring the experimentation phase, the most viable and sound prototyped policy options can be tested on a smaller or time-based scale or in a sandbox to assess their real-world impact and effectiveness.

The success of this approach relies on active participation from both the public and private sectors, indicating an area for natural growth where regulation can be part of an enabling environment. This phase allows for careful observation, data collection and analysis of the impact of new regulatory policies on existing market dynamics and consumers, disruption potential and their interplay with broader policy directions and development goals. |

– Assess the results of the experiment and the broader effects on governments, public bodies, consumers and the broader ecosystem. |

|

| Phase 4: Formulation and scaling upBuilding on the input generated during the previous stages, policymakers, regulators develop detailed plans and strategies for addressing outstanding issues based on further research, analysis and stakeholder input.

This phase includes drafting policy proposals, considering various alternatives, and selecting the most feasible and effective solutions to be presented for approval and implementation. |

|

|

| Phase 5: Implementation, Monitoring and EvaluationOnce a policy proposal becomes an approved policy, priorities shift towards putting it into action through the development of programs, regulations and initiatives.

This phase includes allocating resources, coordinating with relevant stakeholders and executing the plan to achieve the policy’s objectives, while systematically monitoring progress, addressing any challenges that arise and assessing the outcomes of implemented policies. In the mid- to long term, this phase focuses on measuring the effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of the policy, providing insights and feedback that inform future adjustments and improvements. It may also involve a comprehensive analysis of the policy’s overall performance and outcomes to assess whether the policy objectives were met, identify any unintended consequences and gather lessons learned to inform future policymaking and potential policy revisions. |

|

|

Insights from global best practicesThroughout the stages of the policy cycle, ICT regulators and established good practices recommend:

Source: Adapted from Global Symposium for Regulators (GSR) Best Practice Guidelines |

Context and scheduling matters

The timing of a consultation matters not just for when we think about the policy issue and its maturity in the policy cycle but also the consultations potential conflicts and overlaps with other major issues. Some examples:

- Public holidays and major religious events

- Election periods, particularly regional and national elections

- Periods when children are out of school or when the legislature is out of session

Elections: Elections can be critical periods for policy-setting and regulation. If a consultation is planned to happen during an election year, it should not coincide with the periods immediately before, during and after the elections. Depending on the political dynamics of a country, elections may affect policy and regulatory discussions and decisions. Some regulators might have formal restrictions applied on them during election periods to not conduct major, non-emergency external activities, such as a consultation.

Election years may be suitable for carrying out consultations on technical topics; they may however bring additional challenges to more strategic and politically sensitive topics, such as national development strategies, digital transformation agendas or tax policies. For topics that may be prone to political contention or are likely to be affected by a change in government or the distribution of powers, the degree of urgency and importance of the consultation during an election period must be carefully considered.

Not too often: It is also important not carry out consultations too close in time with each other or during periods likely to affect participation (e.g., cultural celebrations, holiday season) so to give sufficient time to stakeholders to engage. Especially if one of the topics is with higher political importance or potentially has greater impact on some stakeholder groups, the risk is to have too few contributions to the other consultation or a lower level of engagement, not allowing for the making the best, most informed decisions.

Regional approach: On issues of trans-border nature, consider timing two or multiple consultations on the same or similar topics with neighbouring countries, and possibly also coordinating on the format, questions and guidelines. This would work towards interoperability among national policies and frameworks from the outset rather than having to engage in regional harmonisation efforts on already adopted national rules.

PILLAR III: PRACTICAL TIPS FOR TIMING CONSULATATIONS

| Step | Guiding questions | Decision-making/Action |

| Time it right |

|

|

PILLAR IV: MANAGE THE PROCESS

This section covers the common ‘process’ steps of a public consultation. It starts by looking at key structural factors for a regulator to prepare itself for consultations within its policy- or rule-making process. Preparation includes staffing, communications, and record keeping. It then moves onto brief examples of different types of public consultation.

| In this section…Policymakers will see how regulators across the globe conduct various kinds of public consultation and the preparations that go into a consultation exercise. With this knowledge, readers can begin comparing their available resources (financial, logistical, and human) against their ambitions and make decisions on what consultation activities to prioritise in terms of desired outputs and communities involved. |

Preparations

Why go through the effort of conducting a consultation without knowing how much it will take and how it will feed into the policy process?

Before setting out a public consultation, regulators need to arrange their own affairs that surround it. In particular, this includes planning activities that are necessary before the start. Some of these relate to the regulatory framework and good administrative practice. Others relate to the internal resourcing requirements.

Resources are an essential starting point. Regulators need to consider the availability of staff time and the prospective financial burden of conducting the consultation. For Ofcom, in the UK, its consultation on network neutrality required the equivalent of ten to twelve full-time employees to run it over the span of the consultation’s lifecycle of several months. In addition, depending on the method of consultation, regulators may incur costs for facility hire, interpretation/translation costs, or travel costs for staff.

Resourcing decisions have implications for budgeting within a regulator. The financial resource available for consultation-related activities will have an important impact on the scale of what a regulator is able to achieve. This may then require planning cycles for a consultation to be months in advance of when the consultation would actually take place. It will also require high-level support for a consultation as part of the policy process. Reports like this and comparative practice illustrate the value that many regulators see in consultations and can be a point of support for early advocates for new or expanded efforts in public consultation for ICT regulation.

Communication planning will be a critical part of the consultation process as well. Regulators will need to consider which channels to use, what information should be made public, when it should be shared, and how this fits within other strategic priorities for the regulator. In addition to formal channels, regulators may want to rely on pre-existing relationships and social media to engage stakeholders in the consultation process. For example, when Indotel in the Dominican Republic looked to revise its amateur radio regulations, it emailed radio clubs within the country to specifically alert them to the upcoming consultation.

Stakeholder outreach strategiesAdapting the format and vehicles of consultations to engage large public audiences effectively involves a strategic approach that ensures inclusivity, accessibility, and meaningful participation. Here are some key strategies:

By employing these strategies, governments can effectively adapt the format and vehicles of consultations to engage large public audiences, ensuring broad, inclusive, and meaningful participation in the policymaking process. |

Information management is also an important part of the process. Among others, Singapore’s IMDA maintains a part of its website dedicated to public consultations. This section lists open, pending, and closed consultations and allows stakeholders to see all relevant information on a consultation, including papers from the regulator, comments and feedback received, and final decisions, in a single place. This is a common practice shared by other regulators interviewed, as well. Countries like Chile, Jordan, Italy, Vanuatu or India keep on record past public consultations, which allows for a more transparent public information. Should regulators consider a similar practice, they need to plan the management of this resource, uploading documents, and keeping it up-to-date with current information on public consultations as they mature.

In addition, regulators should be mindful of their record keeping responsibilities from the beginning. In the UK, Ofcom maintains internal records for audit and record keeping purposes in addition to the statements that it makes publicly available. These records can then be used as evidence of the decision process and in reviewing a consultation’s outcome.

- A regulator’s legal framework may determine a large part of the record keeping requirements. Make sure to seek appropriate legal guidance on what requirements may apply in your country.

These issues – resources, budgets, communication channels, and record keeping – illustrate some of the crucial initial aspects of planning for a public consultation. As regulators’ practice matures, many of these planning steps will become easier to manage and built into the habit of regular consultation. This can help create new efficiencies for regulators to continue consulting with stakeholders but should be part of the timeline for visualising how long the consultation process takes for a regulator.

Initial statement

Most formal consultations start with an initial statement by the regulator. This document sets out the scope of the consultation and guides stakeholders on what issues their participation should be focused. They set out timelines, legal basis of the consultation, and important background information. Many will also set out specific consultation questions to be answered by participants. It might be phrased as an invitation for consultation or ‘call for evidence’ from stakeholders.

How regulators set out this document can determine how other stakeholders engage. Many regulators interviewed stressed the importance of an appropriately defined scope for a public consultation as a key ingredient for its success. A structured and transparent approach enables regulators to collect evidence and build towards a more successful outcome while engaging stakeholders in way that is meaningful both for themselves and for the regulator.

Interview insights: Examples of consultation topics and outcomes

Insights from global best practices Various editions of the GSR Best Practice Guidelines recommend using public consultations:

Source: Adapted from Global Symposium for Regulators (GSR) Best Practice Guidelines |

Time period

One of the largest time blocks in the consultation process is typically the period for receiving inputs. There is some variety in the length and the formality, but many interviewed regulators noted that they have weeks-long consultation periods that are designed in accordance with the mandatory minimums within administrative justice principles within the country.

Most of the regulators we interviewed set time periods around 30 days/four weeks or longer, which is consistent with international best practices[4] – and policymakers should adopt a similar baseline, adapted to local contexts and needs.

- For example, Arcep France announces its public consultations via a communiqué that is available on the Authority’s website. In general, the consultation is fixed for a period of 30 days: this can be shortened in exceptional circumstances, or Arcep can also extend the consultation period at its discretion.

- In the Caribbean, ECTEL’s consultation on spectrum fees for the Ka band was originally set for a two-week period in early December 2021. After receiving requests for an extension from stakeholders, ECTEL extended the consultation for another four weeks to mid-January, with a further two-week period after for replies based on the comments of other stakeholders.

While consultation periods are the formal cornerstone for the regulatory practice, regulators may benefit from not limiting their stakeholder engagement to just this period. By engaging with stakeholders on a regular basis, regulator can help stakeholders anticipate consultation periods and scope to provide timely and comprehensive responses while ensuring that the process does not become a burdensome delay on the regulator’s responsibilities.

Some examples of this good practice can be found in Pillar III, Time it Right.

Means of consultation

How a regulator conducts its consultation offers broad possibilities for creativity and innovative practice along with more traditional formats, based on the regulator’s resourcing and desired inputs.

Most regulators conduct formal, written consultations with structured deadlines and formats based around correspondence between the regulator and its stakeholders. This practice has a number of benefits: the documentation provides a formal record of the evidence provided, how it is incorporated into the consultation’s decision-making process, and the timeline of the consultation. These may be elements critical to administrative law that are relevant to the legal review of regulatory decisions taken as part of a public consultation.

However, beyond this formal practice, a number of regulators took intentional steps to use new formats and approaches to engage new audiences and collect new evidence.

- A roadshow of public workshops in South Africa

- Live streamed hearings in Canada

- Online participation portal in Brazil

- Public news stories in Singapore

- Accessible formats in UK and Canada

- Roundtables in the UK

- Video consultations in the UK

- Social media in France

- Stakeholder meetings (bi-lateral or multi-lateral)

- Focus groups

- Surveys

In South Africa, the regulator held public workshops in multiple cities in the Eastern Cape to collect feedback. Workshops like this allow for more rapid exchange of views between stakeholders and the regulator and can draw in new audiences that may not normally participate in more formal consultation exercises. It can also allow for stakeholders to interact with each other and respond to each other’s contributions within the context of a well-organised workshop.

Interview insights: Arcep France

|

In particular, workshops can enable civil society groups and consumer associations with a subnational focus to potentially find a relevant role within the consultation process. For example, Indotel, from the Dominican Republic, noted that the formality of a written process can create distance between the regulator and stakeholders who are less frequently involved in regulation or administrative processes. Regulators in countries with lower literacy rates or large gaps in education levels may also be able to benefit from this method in engaging with people and communities who might be less confident with a formal, written process – but whose feedback is essential to inform decisions which may affect them.

Canada’s regulator, CRTC, also uses public hearings in its consultation process and did so as part of its consultations on telecommunications services in its northern areas. In addition to running the hearings, the CRTC provides written transcripts of the hearings and also collaborated with the Canadian public affairs channel CPAC to make the hearings available online as livestreams and recordings. This can further enhance engagement – particularly by persons with disabilities who might require assistive technology to participate fully – and also help document the evidence collected in later analysis and review stages, much as with written submissions.

New formats and technologies can help make public consultations more inclusive. Much as the CRTC used livestreams for its public hearings, Ofcom in the UK provided transcribed videos and videos in British Sign Language (BSL) to enable participation by the Deaf community within its consultation the introduction of a video relay service for emergency services. In addition, it permitted individuals to submit videos in BSL as part of the consultation.

Technological innovation can also enhance the consultation process for stakeholders. In Brazil, Anatel operates Participa Anatel, a public engagement hub on the regulator’s website, in accordance with its formal structures and consultation procedures. Anatel also uploads the recordings of public consultation sessions on their YouTube channel. CRTC Canada also introduced a dedicated consultation platform, CRTC Conversations. Through these online portals, stakeholders can read relevant information and make their own submission to a consultation.

In addition to the formal process, regulators may benefit from more informal structures such as roundtables and bilateral engagements with invited stakeholders. For some regulators, this can be part of business as usual and a part of their holistic approach to the consultation process.

Such activities enable the exchange of views between the regulator and stakeholders, add clarity to the process (before and after submissions from either the regulator or the affected stakeholder), and build long-term relationships. For ECTEL, the multi-country Eastern Caribbean regulator (covering the Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), this responsiveness was critical to their management of consultations and providing extensions to meet stakeholder demands.

However, in these, regulators need to ensure that no stakeholder receives an informational advantage by participating in a roundtable or bilateral meeting.

Another form of stakeholder engagement conducted by a number of regulators was through public media such as newspapers. In Singapore, Myanmar, the Dominican Republic, among others, regulators regularly engage with media outlets to announce consultations and further encourage participation from those who might not regularly engage with the regulator or visit its website.

Some regulators also promote ongoing engagement in consultations. In Mexico, the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT) allows stakeholders to subscribe on their website to email alerts regarding public consultations, as a complementary channel to timely inform interested stakeholders about new opportunities to engage.

These examples demonstrate the diversity of possible methods for regulators in engaging with stakeholders through public consultations. The formal written procedure, based on the correspondence between the regulator and stakeholders, is a baseline practice and the most popular format for consultations. However, many regulators are exploring new methods that enable them to enhance their consultation process, appeal to new audiences, and collect new evidence that better informs the decisions they ultimately take.

PILLAR IV: PRACTICAL TIPS FOR DESIGNING, LAUNCHING AND CONDUCTING A CONSULTATION CAMPAIGN

| Step |

|

|

| Define the topic |

|

|

| Get a formal green light |

|

|

| Prepare a consultation strategy and a roadmap, defining objectives, roles and responsibilities, consultation formats, vehicles and channels, and a timeline | ||

| Identify partners/co-leads (if applicable) |

|

|

| Define the format of the consultation (e.g. questions, draft regulation, polling) |

|

|

|

What are those for which we are able to allocate sufficient human and financial resource? |

Pick a single format of a combination of vehicles mindful of the specificities of the topic and the resources available |

|

Do we want/ can we engage simultaneously with all stakeholders, through all channels, or shall we stagger the process [into individual sprints]? |

Analyse how you can make best use of the various channels, also considering new ways or adapting existing scenarios to the topic/constituencies |

| Define a timeline (for stakeholder consultation and the full process) |

Is the timeline clearly established? Does it follows international standards? Is there a second round of consultations included? |

Define the main milestones of the consultation (e.g. publishing consultation document, public hearings/townhalls, social media campaign, closure of consultation, finalising and publishing final outcome) and define a timeline considering the requirements defined above |

| Form an internal team |

Who takes ownership of the process (e.g. management roles, departments, subject matter experts)? |

Provide staff with training on designing, carrying out and M&E of public consultations |

| Allocate resources |

How to make the case to management of the need of sufficient resources to ensure the planned activities are successfully carried out (e.g. reaching out to key audiences, getting external expertise) |

To the extent possible, plan a campaign for the following budget year and include in the annual budget provisions for the funds required for the consultation |

| Prepare a consultation document |

Are multiple languages required? Can we support translations? |

Consider the use of multiple languages to communicate with stakeholders and receive input |

| Launch consultation |

|

|

| Manage activities during the consultation window |

|

|

| Close consultation or extend deadline for submissions |

|

|

PILLAR V: MAKE IT COUNT

A successful consultation is determined by the quality of the results in a regulator’s decision-making process. This starts with the integration of consultation feedback and evidence into the policy or regulation developed. Beyond that, a successful, sustainable consultation practice goes beyond this to consider steps of closure such as how the consultation report contributes to a culture of stakeholder collaboration on regulatory and policy issues and evidence-based decision-making. Open and regular feedback loops engage the stakeholder community around the regulator, also encouraging participation in future consultations and other regulatory activities.

This section talks about analysing evidence collected, publishing the results of the public consultation, and developing a feedback process between regulator and its stakeholders to encourage a positive and sustainable consultation practice.

| In this section…After engaging stakeholders and collecting their inputs, policymakers have to analyse and incorporate these inputs as part of the final stages for a policy or regulatory decision. Beyond the context of a single consultation, regulators can undertake certain activities to develop long-term relationships with stakeholders and develop a participatory culture. The comparative analysis of regulatory practices outlines the steps that follow a consultation, including how stakeholder inputs are incorporated, information is disseminated, and feedback loops are closed to encourage ongoing engagement. |

Analysis of the collected evidence and informing decisions

Incorporating feedback from public consultations allows regulators to better align their decisions with the realities and concerns of stakeholders, ensuring that regulations are effective and relevant. This approach also strengthens the legitimacy and credibility of the regulator, helping to fulfil its mandate of serving the public interest and maintaining trust.

Conducting a thorough analysis of stakeholder input and meaningfully incorporating it in draft regulations or policies require time and resources. Indeed, some regulators noted that the size of the team dedicated to a consultation depends on the quantity of responses (including their length and technical nature). Although it is difficult to accurately foresee the amount of input received, the human resources needed for the analysis should be accounted for in the regulator’s planning stages.

Feedback from stakeholders can help inform the decision ultimately made. For example, industry participants can help give greater detail to any potential market impacts of a decision taken and a stronger cost-benefit analysis conducted by the regulator. Another example would be consumer groups and civil society organisations informing and evidencing where consumer harm might exist in a particular part of the market. These are ways that a regulator can bring in the feedback from a public consultation to inform and evidence a regulator’s decision that make it more reputable and trustworthy from among all stakeholders.

In addition to the value of integrating stakeholder perspectives and contributions into the regulator’s ultimate decision, a number of regulators have the practice to reply to comments received and make replies publicly available. For example, in Mexico, the regulator has rules that require the publication of a Considerations Report that includes stakeholder submissions submitted in time and the regulator’s response to it. This means that the regulator has to commit not only to analysing comments, but to communicating its position on individual issues as well.

- CST, Saudi Arabia: Immediately after the end of the time specified for receiving the comments, CST analyses all the responses from all participants in the consultation and responds to every set of comments received, and then begins updating the regulatory document with the relevant input and completing the approval process. In addition, and after the end of the consultation, CST also publishes a report to the public on the results of the public consultation on its Regulatory Platform (see an example of the report).

| Keeping recordsDocumenting public consultations and following due process to integrate stakeholder input significantly enhances evidence-based decision-making and regulation.

As a matter of good practice, organizations are encouraged to document the various phases of a consultation from its inception and design to its implementation to the decision-making process and outcomes it enables.

By rigorously documenting and following due process in public consultations, policymakers can create a robust framework for evidence-based decision-making. This approach not only improves the quality and relevance of regulations but also fosters greater public trust and engagement in the policymaking process. |

Publishing comments and confidentiality

A number of regulators publish not just their ultimate decision but also the comments received from all stakeholders as part of the consultation. Regulators noted the transparency that this permits but also flagged the need to handle informational sensitivity with their publications.

The confidentiality of stakeholders’ responses was a key issue mentioned by several regulators.

- In France, Arcep ‘publishes the totality of responses that are sent, with the exclusion of pieces of information covered by business confidentiality.’

- Similarly, CRTC asks stakeholders submitting business confidential information in a consultation response to submit a second version without such information to be included in the final publication of results.

- In the UK, Ofcom adds a [scissor icon] to the published versions of submissions received to indicate where confidential information has been redacted.

Interview insights: Arcep France

|

In addition to inputs received, a number of regulators also published reports and studies that they commissioned that were relevant to their decision-making process. In Canada, CRTC published its public opinion research report as part of its review of the state of telecommunications in its Far North. In the UK, Ofcom publishes much of its consumer survey data that informs its regulatory decisions, such as pricing trackers.

Publication

After an initial statement, consultation period, and analysis, regulators publish the final results of their consultation. These consultation statements come in a variety of formats. When regulators are able to add detail and make more comprehensive final reports, this lends credibility to the consultation and to the regulator’s decision-making process.