Cross-border collaboration in the digital environment

30.09.2020The digital environment is global in nature. For example, Internet users in most jurisdictions can typically view websites and content from anywhere in the world, subject to copyright or other limitations. Global e-commerce enables buyers in one country to purchase goods and services from sellers in another country. With online communications, people can video conference, call, and message for free or at relatively low cost, regardless of location or borders. Billions of these transactions occur daily, involving every sector. This, in turn, raise issues for governments in terms of how to address a host of cross-border issues, including data privacy and consumer protection, as well as public safety and national security, among others.

Governments are finding that, in an increasingly digital world, national laws and policies must often be harmonized on a regional or international basis in order to ensure that their citizens and businesses can access global markets and to fully realize the benefits of a digital economy. Establishing workable international standards and frameworks can promote regulatory harmonization, enable industry players to leverage economies of scale to better deliver new technologies and services around the world, and avoid a patchwork of regulations that may be contradictory from one country to the next. This approach expands on the institutional collaboration model to encompass collaboration at the global level. Three key areas of international harmonization are highlighted below, namely cross-border data flows, technical standards for equipment and devices, and taxation of digital services.

International frameworks to promote cross-border data flows

The digital economy provides multiple economic opportunities, and cross-border data flows remain a critical component of today’s digital trade, as they have a significant impact on economic growth. For instance, the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that, over the past decade, global data flows accounted for USD 2.8 trillion, “exerting a larger impact on growth than traditional goods flows” (McKinsey 2016). In its Visual Networking Index (VNI), Cisco predicted that global IP traffic – serving as a proxy for data flows – would grow from 122.4 exabytes per month in 2017 to 396 exabytes per month by 2022, a three-fold increase in just five years (Cisco 2018). Thus, the economic impact of data flows will continue to soar over the coming years as broadband penetration increases and the number of connected devices expands, spurred by the Internet of Things (IoT).

Although much of these cross-border data flows involves non-personal data (i.e. data that does not contain personally identifiable information, such as name, gender, or contact information), the transfer of personal data between jurisdictions poses major challenges in terms of protecting citizens’ information and rights to privacy. Countries are responding to cross-border transfers of personal data in a variety of ways. Some countries have few to no restrictions on how personal data may be transferred overseas whereas others adopt strict conditions, with some severely restricting cross-border transfers by imposing data localization obligations that prohibit personal data from being transferred outside of the country. While protecting personal data privacy is an important policy goal, restrictive regimes can hinder the development of the digital economy and reduce GDP, especially for developing countries seeking to gain access to foreign markets and investment. Data localization mandates can particularly impact financial and communications services, two key industries in the digital environment.

At the core of digital transformation strategies, harmonized data protection frameworks and international cooperation instruments constitute essential mechanisms to streamline data flows, reducing the cost associated with data trade. These regulatory developments influence regulation at the national level, helping countries adopt best practices and operate in a harmonized manner at the regional and international levels.

The APEC CBPR system

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), a regional economic forum composed of 21 member states focused on ensuring cross-border trade, initially adopted the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system in 2011. The CBPR seeks to balance the flow of data and information across borders while effectively protecting personal information. Under the CBPR, companies located in signatory countries can become certified by an independent third party, called an Accountability Agent, which evaluates and certifies the companies’ privacy policies and practices.

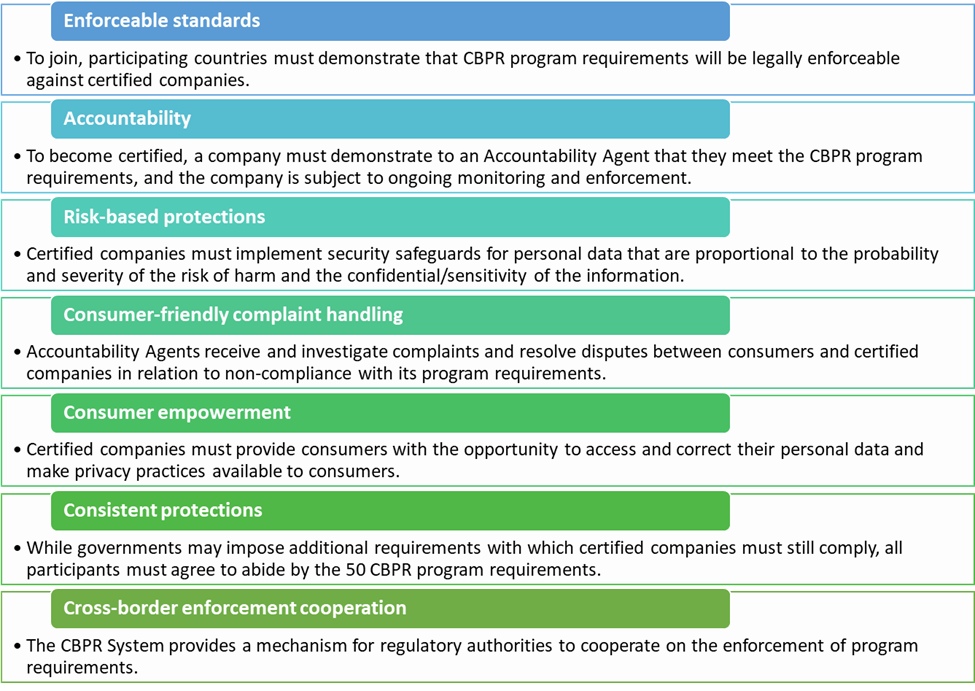

CBPR requirements for certified companies and participating countries

Source: APEC.

CBPR-certified companies must follow the baseline set of rules established in the APEC Privacy Framework. This framework is intended to promote a flexible approach to information privacy protection across member economies, while avoiding the creation of unnecessary barriers to information flows. To date, nine jurisdictions have joined the CBPR system including Australia; Canada; Japan; Republic of Korea; Mexico; the Philippines; Singapore; and the United States.

APEC continues to focus on facilitating technological and policy exchanges among member countries, particularly in promoting cooperation to develop the digital economy. The 2017 APEC Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap built on previous initiatives and serves as a framework to guide member states on key areas and actions, including to promote “coherence and cooperation of regulatory approaches affecting the Internet and digital economy,” and to facilitate the “free flow of information and data for the development of the Internet and Digital Economy, while respecting applicable domestic laws and regulations,” as presented in the box below.

APEC Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap: cooperation as a key focus area

“Promoting coherence and cooperation of regulatory approaches affecting the Internet and Digital Economy: A core problem facing both large enterprises and MSMEs is how to address legal and procedural uncertainties and to ensure compliance with an alphabet soup of general and sector-specific laws and regulations, as well as codes of practice and legal judgments. To accelerate the growth of the Internet and Digital Economy, member economies should promote mutual understanding and strengthen cooperation in approaches to regulation, including international and technical standards, while respecting each economy’s choice of policies which are consistent with domestic situations and international legal obligations.”

Source: APEC 2017.

Convention 108 + and the GDPR

Another important international instrument aimed at protecting the rights and privacy of individuals and their personal data treatment is the Council of Europe 1981 Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data and its 2018 amending protocol (Convention 108 +) (Council of Europe 2018). This treaty was the first international binding instrument on data protection, requiring the signatories to incorporate its principles in their national frameworks, as well as its sanctions and remedies. The 1981 convention formed the basis for international data protection frameworks in over forty European countries, and influenced the now-repealed Directive 95/46/EC; it also helped to shape policy and legislation beyond Europe’s borders in numerous countries around the world. In 2018, the amending protocol was released to harmonize the convention with various international data protection instruments, including the European Union (EU) data protection package, and particularly, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

According to Convention 108 +, a transborder data transfer occurs when personal data is disclosed or made available to a recipient subject to other country’s jurisdiction or to an international organization. The treaty’s provisions on transborder flow are aimed at facilitating the free flow of information and ensuring that data processed within the jurisdiction of a party, and which is subsequently transferred to a state that is not a party to the convention, is always processed with adequate levels of protection.

Convention 108 + also provides for cooperation and mutual assistance between parties via their supervisory authorities responsible for ensuring compliance with the provisions of the convention. These supervisory authorities must cooperate with one another to the extent necessary for the performance of their duties and exercise of their powers (article 17 of Convention 108). This mutual assistance can involve different practices, from sharing information and documentation of their law and administrative procedures, to sharing confidential information, including personal data. Particularly, in order to organize their cooperation duties, the convention requires parties to form a network of supervisory authorities. As of May 2020, 55 states have ratified/acceded to the convention.

Another significant development in terms of harmonized data protection frameworks and international cooperation mechanism is the GDPR (Regulation (EU) 2016/679). This EU instrument aims to procure a consistent and high level of protection of natural persons, removing the obstacles to personal data flows within the EU. To meet these goals, the protection level of the rights and freedoms of natural persons regarding the processing of such data must be equivalent in all Member States. Additionally, consistent application and monitoring of the data processing rules, as well as equivalent sanctions, should be ensured throughout the EU. For enforcement, the GDPR relies on independent national data protection authorities (DPAs) and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), composed of the representatives of the national data protection authorities and the European Data Protection Supervisor. Particularly, the EDPB fosters consistent application of data protection rules throughout the EU and promotes cooperation between data protection authorities in compliance with the GDPR.

The GDPR provides for the effective cooperation between the supervisory authorities of different Member States as well as with third countries and international organizations (articles 50, 60 and 61). For instance, the GDPR states that supervisory authorities must provide each other with relevant information and mutual assistance in order to implement and apply the GDPR in a consistent manner. They must also put in place measures for effective cooperation with one another. Mutual assistance must include, in particular, information requests and supervisory measures, such as inspections and investigations.

Today, the GDPR is a reference point for data protection regulation and has influenced many other regulatory frameworks around the world. This trend has enabled the convergence of data protection standards at the international level, facilitating data trade flows (EC 2020).

Adoption of international technical standards for type approval of equipment

Numerous ICT/telecommunication regulators have incorporated rules, standards, and specifications for products and systems deployed and used in their territories. These rules can be adopted to protect public health and safety, promote the efficient and effective use of spectrum, and to achieve adequate levels of electromagnetic compatibility (EMC). That is the case, for example, in the EU (EU Radio Equipment Directive).

Equipment and system users as well as national regulators require evidence that devices and systems conform to the applicable standards and rules and that they can interoperate with each other as required. The process to obtain evidence of compliance with these standards and rules is called conformity assessment (ITU 2015). When risks associated with nonconformity are low, a supplier declaration of conformity may be enough to demonstrate compliance. On the contrary, when nonconformity risks are considerable, regulators might require further assurance that the equipment conforms to applicable standards and rules. A product certification can provide such certainty to users and regulators (ITU 2015).

According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), type approval is a special kind of certification. It means the equipment is certified to meet certain requirements for its type, whatever that may be, which can include rules on applicable standards, testing, labelling, and record-keeping obligations to supply products (ITU 2015).

Type approval or certificate of conformity processes (also called homologation processes in some jurisdictions) are a key element of, and facilitator for, the effective deployment of new technologies. To support expanded connectivity needs for the next decade, governments will adopt policies and strategies that best ensure that their countries can benefit from the far-reaching impacts of the digital economy, and increase social and economic welfare across all sectors. By adopting streamlining policies and reducing unnecessary regulatory burdens, local regulators encourage not only innovation and investment, but also the deployment of necessary infrastructure and devices that provide consumers and the marketplace easier and faster access to new technologies.

In line with this, countries can focus on supporting ongoing industry development of international standards for flexible, interoperable, and secure solutions and allow market forces to shape standardization efforts to the greatest extent possible. The global standardization efforts conducted through the Third-Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), for example, successfully enables the commercialization of new technologies without governmental intervention. Additionally, in terms of IoT, industry associations, such as the Wi-Fi Alliance, the Bluetooth Special Interest Group, the Thread Group, and the Homeplug Alliance, are developing and promoting specifications and interoperability programs for IoT connectivity technologies. These types of efforts increase effectiveness and allow broad interoperability by reducing fragmentation.

Mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) are another common mechanism among many countries and regions. Many jurisdictions use these types of instruments, allowing parties to share resources and facilitate the flow of products across parties to MRAs. These instruments are based on the solid qualifications of the parties involved, a compatible operational approach, and do not require a harmonized technical or administrative framework (ITU 2014). According to the EU, parties to MRAs are at a similar stage of technical development and have comparable approaches on type approval or conformity assessment requirements, ensuring a proper level of protection in terms of health and safety, among other criteria. In line with this, these agreements involve the recognition of certificates, marks, and reports released by the other MRAs party, based on its own legal framework (European Commission 2016).

EU perspective on MRAs

“MRAs are not based on the necessity to mutually accept other party’s standards or technical regulations, or to consider the legislation of the two parties as equivalent. They involve only the mutual acceptance of the reports, certificates, and marks that are delivered in the partner country in accordance with its own legislation. However, MRAs can pave the way towards a harmonised system of standardisation and certification by the parties.”

Source: European Commission 2016

Finally, although global standards help to reduce the duplication of testing across national borders, many countries have also adopted local standards that ultimately result in restriction of trade. Countries that implement restrictive standards include China, India, Republic of Korea, and Vietnam (Ferracane and van der Marel 2018).

Multilateral negotiations on digital taxation

As governments around the world have included digital taxation in their national agendas, multilateral organizations are advancing their goals to consolidate unified mechanisms that address tax challenges in a digitalized economy.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is leading the way by working with more than 135 countries and jurisdictions on the implementation of an inclusive framework to address tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). According to the OECD, BEPS arises from gaps in and unarticulated tax rules across multiple jurisdictions that do not appropriately consider how multinational companies operate in a global economy. These gaps can particularly harm developing countries that rely heavily on corporate income taxes. To address these shortfalls, the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS developed 15 actions to help countries counter harmful tax practices. These actions address issues, such as the nexus (i.e. presence in a particular jurisdiction) and profit allocation (i.e. portion of profits that should be taxed) rules as well as mechanisms to reduce incentives to multinational companies that shift income to low-tax jurisdictions. The OECD is also examining transparency rules and conflict resolution between jurisdictions, among other matters.

References

APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. 2017. APEC Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap. 2017/CSOM/006. Singapore: APEC. http://mddb.apec.org/Documents/2017/SOM/CSOM/17_csom_006.pdf.

Council of Europe. 2018. Convention 108 +: Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/108/signatures.

European Commission. 2016. The ‘Blue Guide’ on the Implementation of EU Products Rules 2016. Commission Notice. C/2016/1958. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.C_.2016.272.01.0001.01.ENG.

European Commission. 2020. Data Protection as a Pillar of Citizens’ Empowerment and the EU’s Approach to the Digital Transition – Two Years of Application of the General Data Protection Regulation. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. COM/2020/264 final. Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0264&from=EN.

Ferracane, Martina F., and Erik van der Marel. 2018. Do Data Policy Restrictions Inhibit Trade in Services? Brussels: ECIPE. https://ecipe.org/publications/do-data-policy-restrictions-inhibit-trade-in-services/.

McKinsey. 2016. Digital Globalization: The New Era of Global Flows. McKinsey Global Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/digital-globalization-the-new-era-of-global-flows#.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2014. Establishing Conformity and Interoperability Regimes: Basic Guidelines. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Technology/Documents/ConformanceInteroperability/CI_BasicGuidelines_February2014_E.pdf.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2015. Establishing Conformity and Interoperability Regimes: Complete Guidelines. Geneva: ITU. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Technology/Documents/ConformanceInteroperability/publications/Establishing_Conformity_and_interoperability_Regimes-E.pdf.

Last updated on: 19.01.2022