Collaborative governance

25.08.2025Importance of collaborative regulation

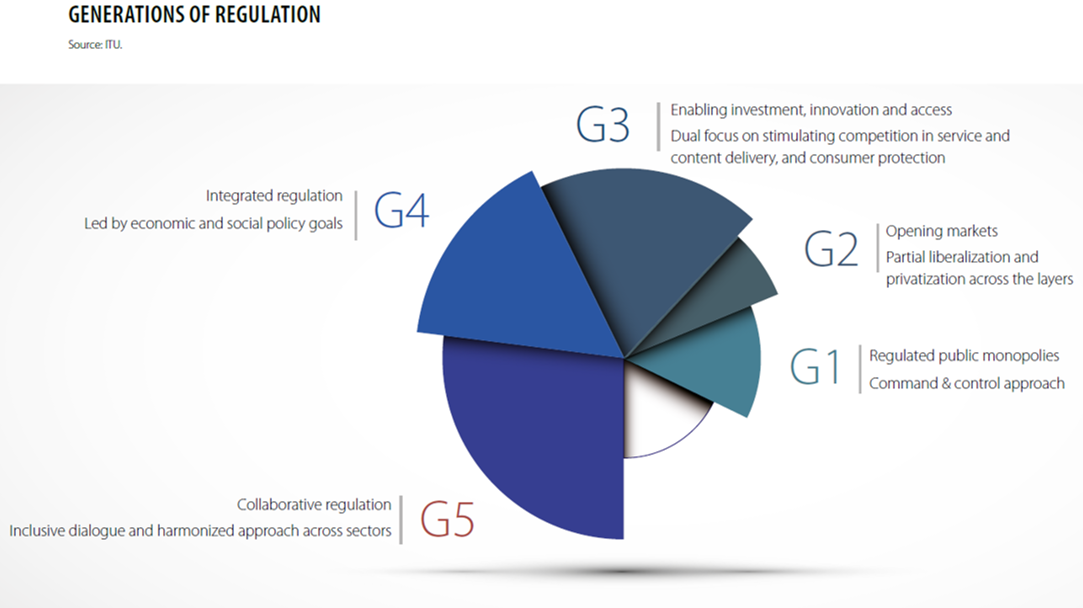

Over the last several years, ITU has developed a comprehensive model for tracking the maturity of telecommunications markets – the Generations of Regulation Model. The model presents a framework for considering how policy and regulation have evolved over recent decades, from a narrower telecommunications focus to a broader ICT focus and ultimately to collaborative digital governance (Figure 1) (ITU 2023a). As presented by ITU, fifth-generation (G5) regulation is framed under the premise ‘collaboration across sectors, cooperation across borders, and engagement across the board.’

Figure 1. Generations of regulation

Source: ITU

Leading G5 regulation is the desired destination point for ICT regulation worldwide. It highlights the increased importance of more flexible and collaborative regulatory frameworks capable of addressing the broad impacts of the digital economy across sectors. Further, it enables stakeholders to create and implement appropriate regulatory frameworks as digital technologies and services continue to evolve.

ITU research and observation points to the need for continued development and implementation of collaborative regulation for the benefit of all stakeholders. This is supported by four key observations (ITU 2023b):

- Digital transformation has placed ICTs at the foundation for every economic sector and as a necessity for business performance and national growth.

- A combination of enabling frameworks and appropriate networks and services are critical to leveraging ICTs to transform sectors and activities, including education, health care, environmental management, agriculture, trade, and entrepreneurship.

- Silo-style ICT sector regulation is not viable in the digital world. G5 regulation reflects the interplay between digital infrastructure, services, and content across industries and borders, while also harmonizing rules and ensuring consistent implementation of policy and regulatory frameworks.

- Collaborative regulation considers sustainability and long-term gains, with leading countries engaged in connecting marginalized and underserved populations. These considerations require more innovative, more collaborative policymaking and regulation.

Key characteristics of countries that have embraced G5 regulation include (ITU 2023c):

- innovative, open, incentive-based, cross-sector;

- navigates towards broad, inclusive, meaningful connectivity;

- centered on people, sustainability, and long-term gains, not on profit-taking;

- fosters vibrant markets and fast-evolving technologies, products, and services that bring social and economic value;

- finds market solutions to challenges as new technologies and business models test existing regulatory paradigms;

- builds consensus that protects consumers while encouraging market growth and innovation;

- features an expanded leadership role for the ICT regulator in driving cross-sector collaboration; and

- lends itself to connecting marginalized individuals, persons with disabilities, those communities of low-income or challenged by educational impoverishment, and remote or isolated populations lacking infrastructure.

ITU tools including the G5 Benchmark and the ICT Regulatory Tracker – and the Unified Framework combining the two tools that was introduced in the Global Digital Regulatory Outlook 2023 – provide insightful data for taking a holistic view of the enabling environment for digital transformation (ITU 2023d). The Unified Framework provides a set of benchmarks that can be used to take stock of the readiness of countries for digital transformation and their policy, regulatory and governance capacity.

Intragovernmental collaboration

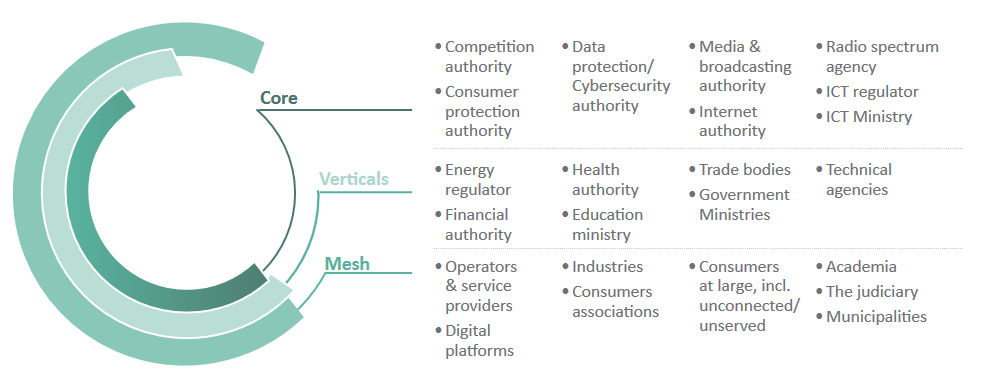

The Intragovernmental Collaboration section focuses on intragovernmental regulatory collaboration – collaboration between and within government agencies. This primarily focuses on the agencies tasked with implementing and enforcing regulatory frameworks, including sector regulators and horizontal regulators, but also taking account of the roles of policymakers and other government leadership. ICTs are a foundational component of a wide range of economic sectors, leading to an increased need for collaboration between ICT sector regulators and the regulatory and policymaking agencies that govern other sectors.

Importance and drivers of intragovernmental collaboration

To make intergovernmental collaboration effective, it is important to consider the underlying drivers that motivate it. Notably, intragovernmental collaboration is crucial in an increasingly digital economy because regulatory authorities—and teams within these authorities—have varied and complementary areas of competence. Bringing these experts and their collective experience together to address both existing and anticipated challenges and developments can result in not only better solutions for government, businesses, and consumers, but also improve the likelihood that the regulatory agencies are working toward common goals.

The need for intragovernmental collaboration is driven by rapid evolution in the ICT sector itself as well as how ICTs are used across the economy. Previously discrete services or regulatory frameworks are increasingly overlapping or affecting each other, creating novel questions of policy, regulation, and enforcement. This ICT sector evolution continues to drive organizational restructuring within regulatory agencies, which itself drives a need for collaboration as new teams are developed and as regulators determine how best to address narrow questions and larger sectoral governance questions. Further, there are periodic intersections of vertical (i.e., sector-specific) and horizontal (i.e., economy-wide) regulations. Matters related to competition within the ICT sector are a frequent example of this intersection.

Approaches to intragovernmental collaboration

Regulators frequently use both formal and informal methods to establish, support, and maintain intragovernmental collaborations. Intragovernmental Collaboration introduces these approaches following a statement of ITU core design principles for collaborative regulation that are relevant to both cases.

- Formal intragovernmental collaborations are established through written agreements, such as a memorandum of understanding (MOU) or memorandum of agreement (MOA), which generally include common components. These establish the problem to be addressed or the goals of the collaboration, identify the participants and their responsibilities, set a duration for the arrangement, and reference any relevant legal frameworks. Critically, such agreements also set out the processes or mechanisms by which the participating agencies will collaborate.

- Informal collaborations are established outside of typical bureaucratic structures and can instead take the form of communities of practice, working groups, training sessions, or other less-formal arrangements to create opportunities for collaboration on issues of shared importance. However, these models can also be limited by a lack of resources and clear decision-making authority.

- Hybrid collaboration models combine elements of both formal and informal approaches, allowing agencies to benefit from the structure and accountability of formal agreements while leveraging the flexibility and responsiveness of informal mechanisms. In practice, this often means operating under a formal framework while relying on regular informal interactions—such as working groups or joint task forces—to coordinate activities, share knowledge, and adapt to emerging needs.

The section is supplemented by two thematic deep dives. Common elements of collaboration agreements between agencies incorporates a more-focused review of common elements of intragovernmental collaboration agreements, presenting real-world examples of language employed to achieve particular goals. These include introduction and background information, objectives, and information on the relevant issue or challenge, as well as common general provisions. Collaboration between competition and ICT authorities examines a common collaborative relationship found in numerous countries. In particular, it discusses the need for collaboration between ICT sector regulators with competition-related obligations or powers and horizontal competition authorities to maximize clarity with regard to competition regulation.

External collaboration

Subsequent sections complement the discussion of intragovernmental collaboration by presenting discussions of external collaborative regulation approaches, namely cross-border collaboration and public/private collaboration.

Cross-border collaboration

The Cross-Border Collaboration section begins by considering different approaches to cross-border collaboration – bilateral agreements, multilateral agreements, and engagement with international bodies. This section provides brief overviews of each approach, including key characteristics and examples. These are followed by a discussion of treaties, MOUs, and multilateral organizations – key mechanisms for implementing cross-border collaborative regulatory efforts.

This section continues with a discussion of methods for establishing cross-border collaboration. Taking an approach similar to the discussion in Intragovernmental Collaboration, this section addresses key steps in establishing a collaborative regulatory arrangement, including identification of objectives, enumerating responsibilities and commitments, obtaining appropriate approval for the collaborative activity, and supporting the collaborative activities.

The discussion of cross-border collaboration concludes with consideration of success factors as well as strengths and challenges of cross-border collaborative efforts.

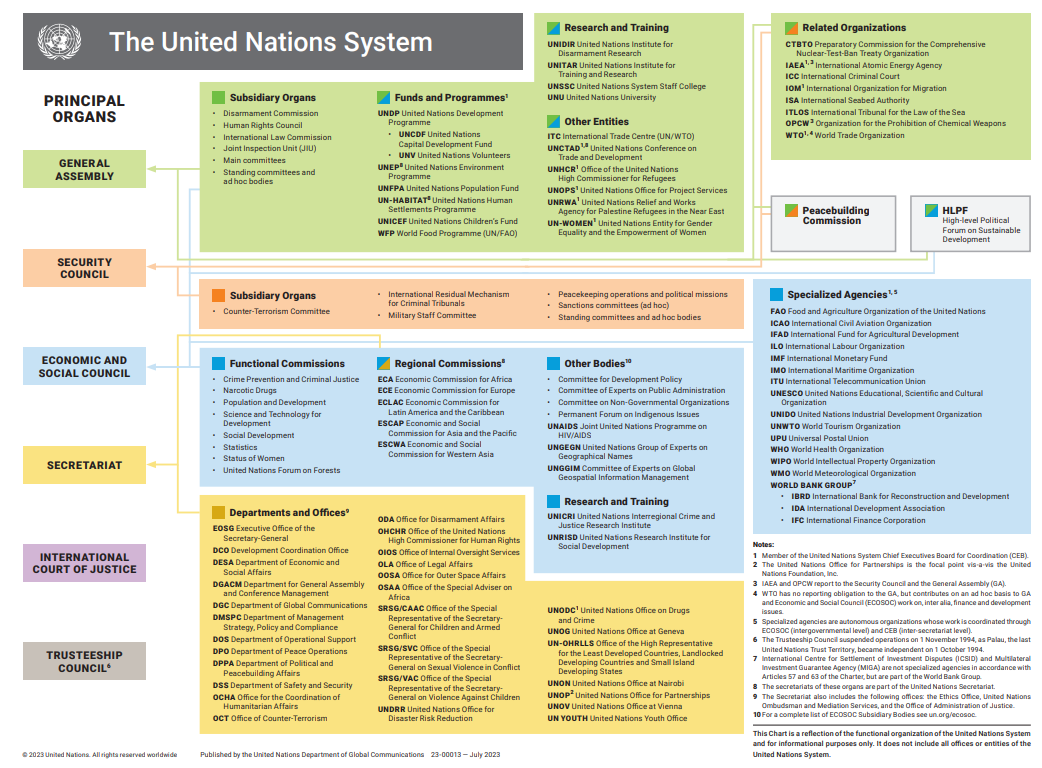

International organization collaboration

The International Organization Collaboration section focuses on collaboration involving international organizations. In particular, it addresses the role of international multilateral organizations, the United Nations system, and donor agencies such as the World Bank Group and regional development banks, highlighting the collaborative opportunities and resources provided. This section also highlights the roles of standards bodies, private sector associations, and non-governmental organizations.

Public/private collaboration

The Stakeholder Engagement section focuses on regulatory collaborations between the public and private sectors, which can provide benefits to stakeholders in both sectors. Public/private collaborations can help to encourage innovation, facilitate deployment of emerging technologies, incentivize investment, and increase buy-in among private-sector stakeholders.

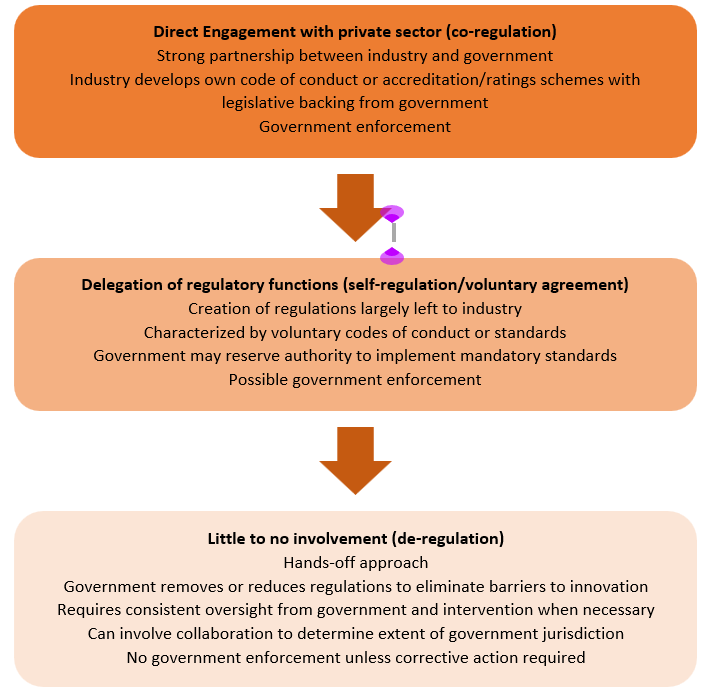

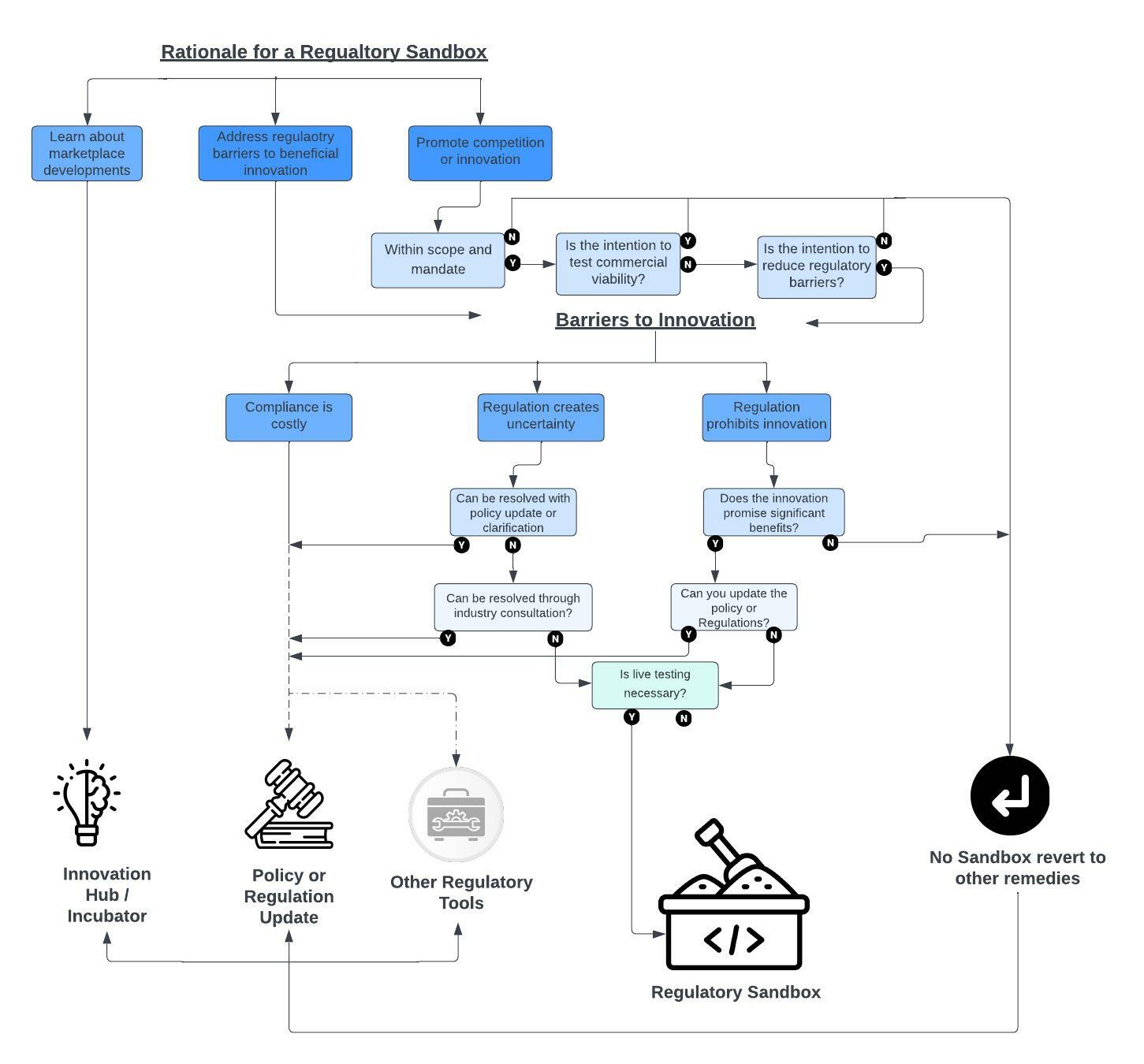

The discussion of stakeholder engagement and public/private collaboration begins with descriptions of key collaborative approaches, including de-regulation, self-regulation, and co-regulation. Each of these has benefits and drawbacks and is marked by differing levels of engagement and enforceability by the regulator. The section also discusses mechanisms for implementing collaboration between regulators and the private sector. These include:

- industry codes of practice,

- public consultations,

- regulatory sandboxes, and

- partnerships with other institutions.

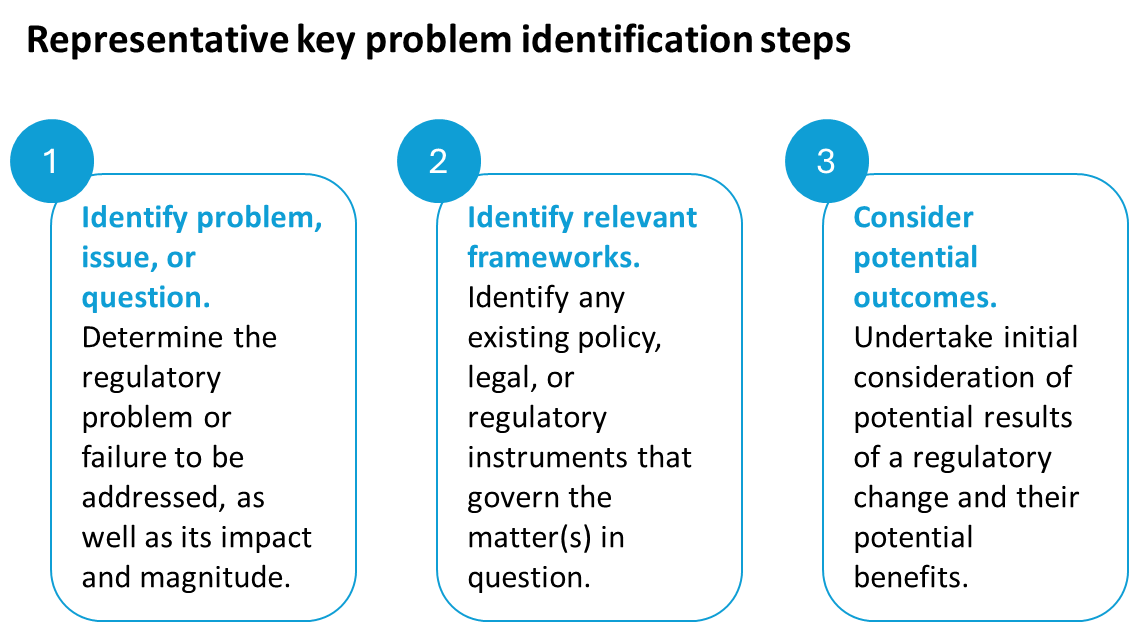

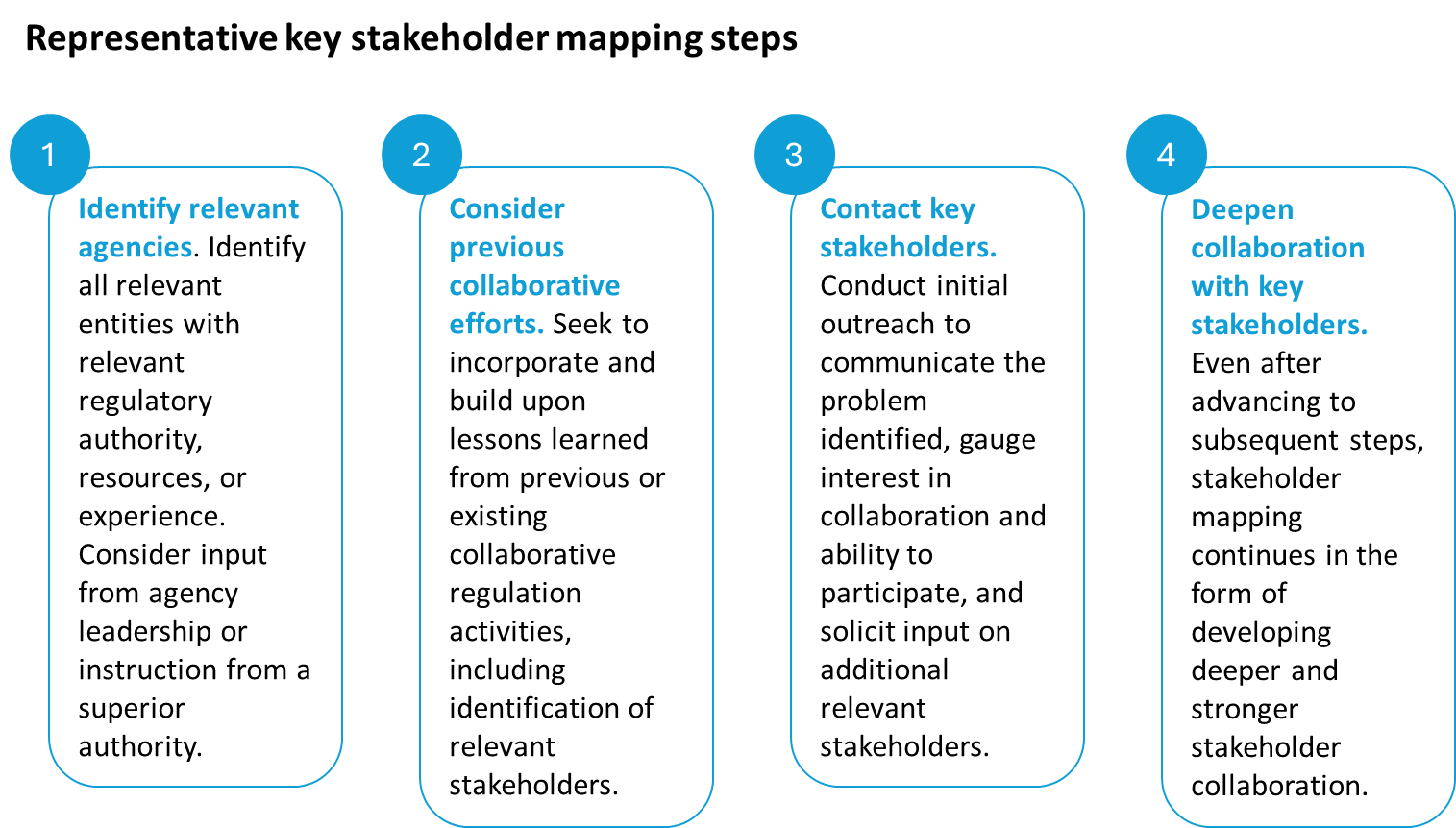

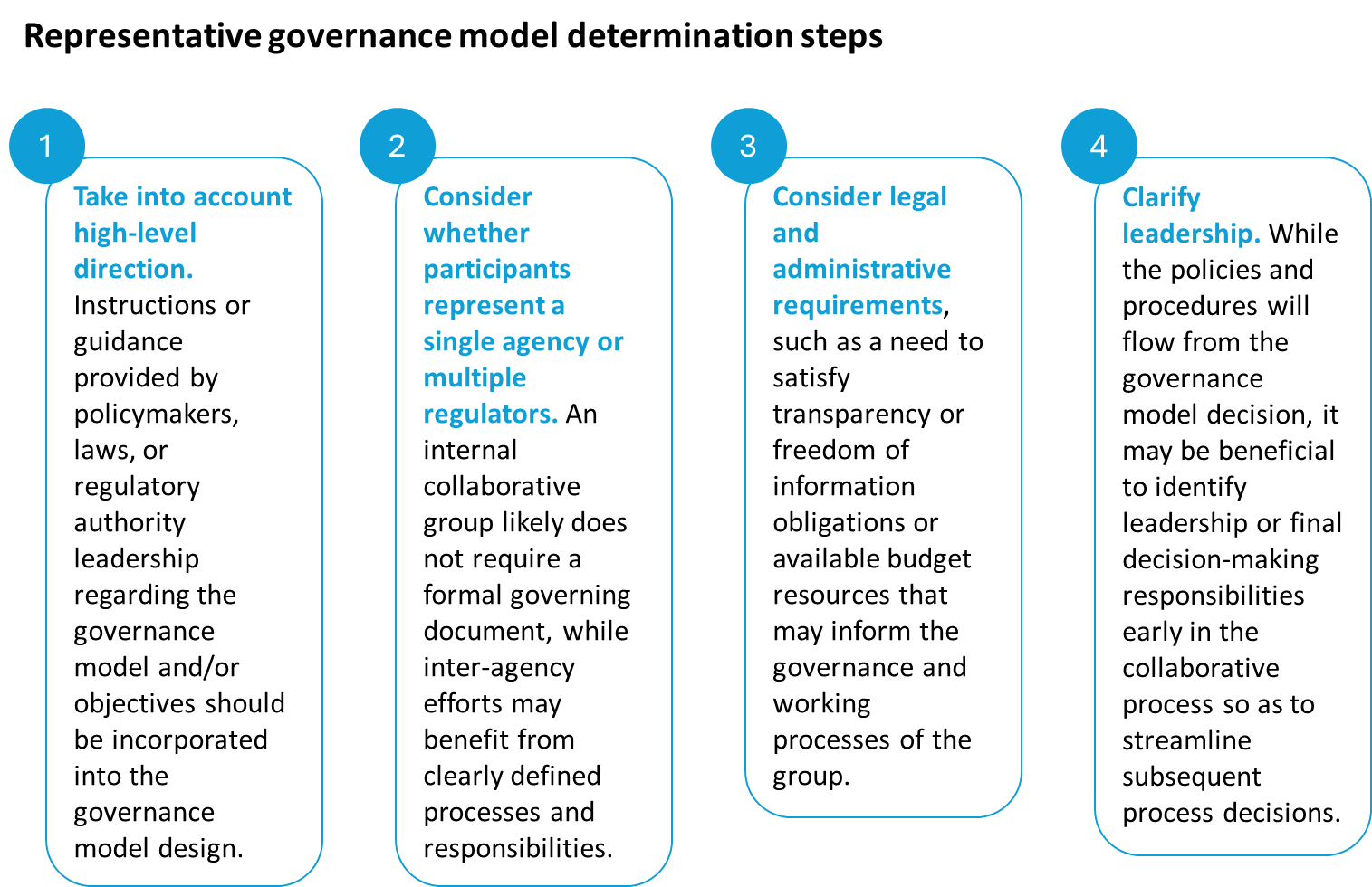

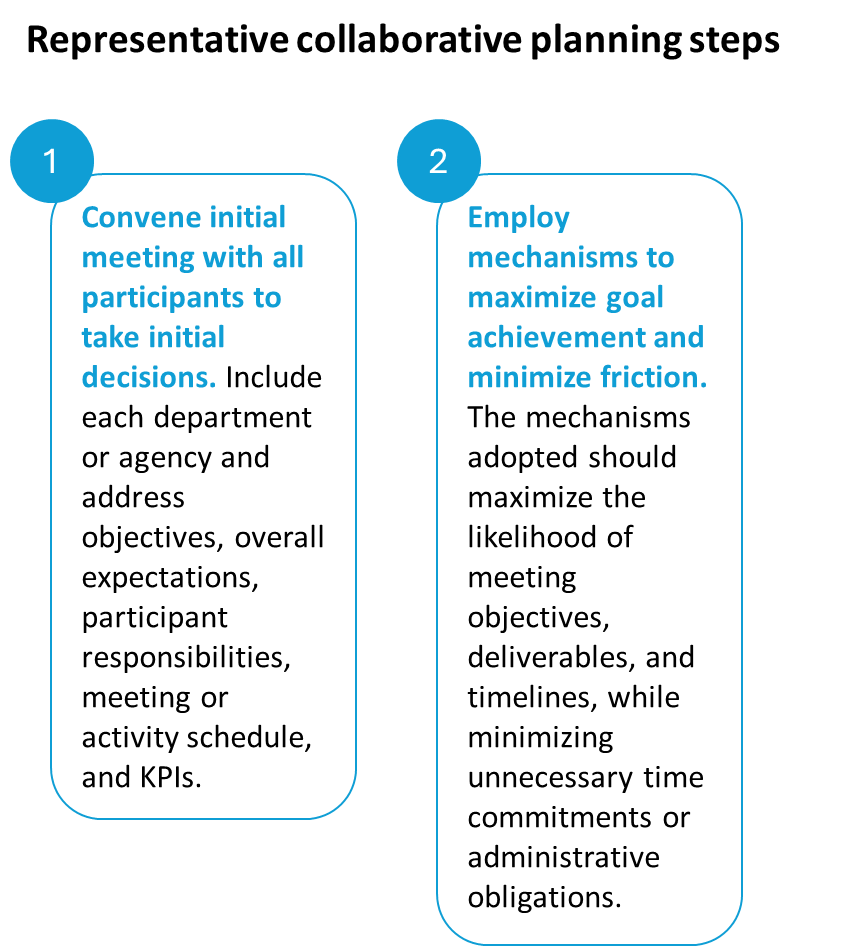

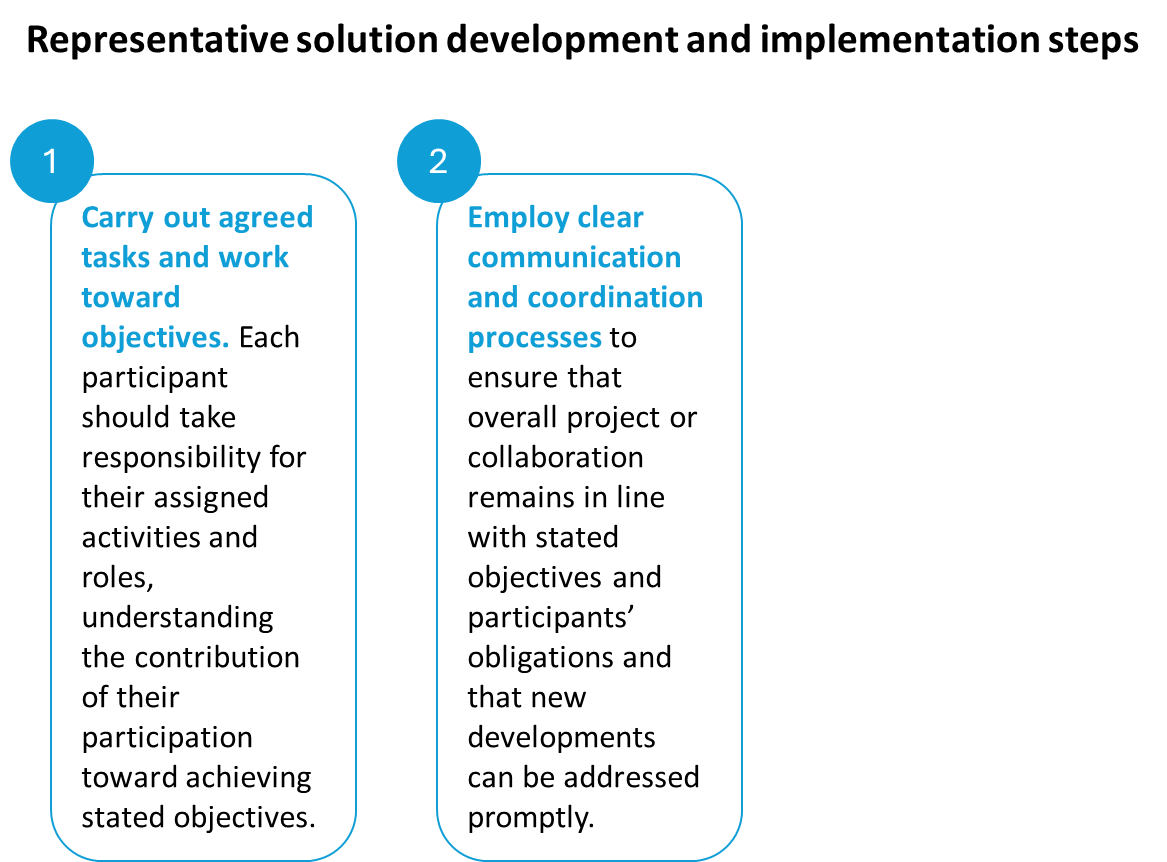

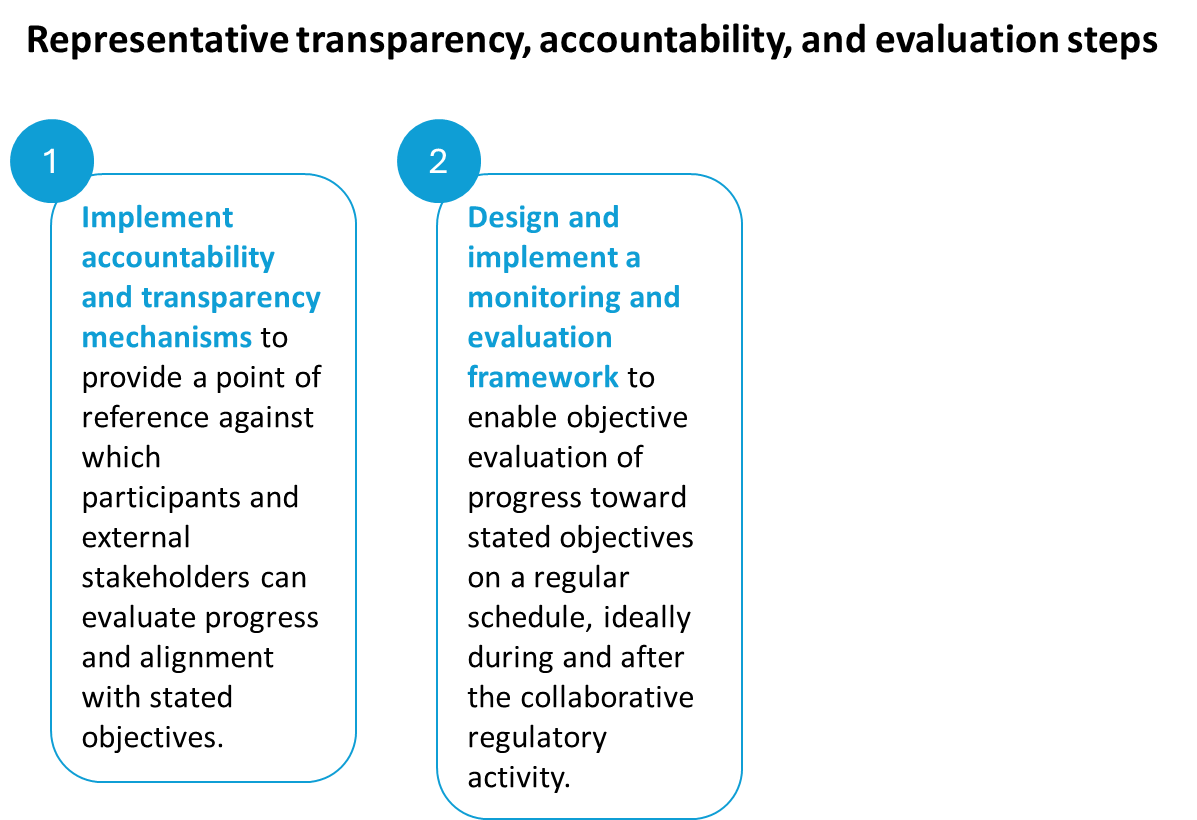

Practical Implementation Steps and Indicators of Success

The final section focuses on practical steps for implementing collaborative governance as well as considerations for evaluating the success of collaborative activities and engagements. The intent of this section is to provide concrete recommendations and topics for consideration as policymakers and regulators consider and design collaborative governance approaches.

The article explores these themes through four main pillars of collaboration:

- Intragovernmental Collaboration: This section focuses on the foundational need for cooperation within a country’s government. It examines the drivers for collaboration, such as technological convergence and the overlapping mandates of sector-specific and economy-wide regulators (e.g., ICT and competition authorities). It details the formal and informal mechanisms, such as Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) and joint task forces, that enable agencies to work together effectively, avoid regulatory gaps, and create coherent national digital policies.

- Cross-Border and International Collaboration: Recognizing that digital markets are global, this section expands the focus to cooperation between countries. It analyzes the role of bilateral and multilateral agreements, regional regulatory associations, and international organizations in harmonizing policies, sharing best practices, and addressing trans-national challenges like cross-border data flows and cybersecurity.

- Stakeholder Engagement: This section delves into the critical partnership between the public and private sectors. It outlines the spectrum of collaborative approaches, from co-regulation and self-regulation (e.g., industry codes of practice) to more hands-off models. It also examines the tools regulators can use to foster innovation and gather evidence, such as public consultations and regulatory sandboxes.

- Practical Implementation and Success Indicators: The final section provides an actionable roadmap for regulators. It outlines practical steps for establishing and managing collaborative initiatives and provides a framework for measuring their success. The focus is on tangible outcomes, such as policy impact, robust stakeholder engagement, and the production of valuable public resources.

By exploring these pillars, this article offers a comprehensive guide for regulators seeking to transition to a G5 model of governance, equipping them with the principles, tools, and best practices needed to build a sustainable and inclusive digital future.

Introduction

In an increasingly complex digital ecosystem, governments must collaborate internally to effectively deliver progress on key policy goals. This is true both within the information and communication technologies (ICT) sector and in the various sectors it enables and affects across the economy. Intragovernmental collaboration—or the coordinated effort between various agencies, departments, offices, and regulators to carry out national policy objectives—is an important avenue by which governments implement collaborative governance principles.

Such collaboration should result in regulations that are evidence-driven, outcome-based, and developed to avoid regulatory blind spots. Collaborative regulatory efforts should include building consensus for implementation, ensuring political buy-in, and developing policy coherence across sectors.

Importance and drivers of intragovernmental collaboration

Intragovernmental collaboration encompasses efforts to coordinate between different regulatory entities (e.g., the ICT regulator and the financial services regulator) as well as collaboration within individual regulatory agencies. As the ICT sector continues to evolve – and as an increasing number of sectors rely on ICT networks and services to provide products and services – regulatory staff with different areas of focus and expertise will increasingly benefit from cross-collaboration and coordinated regulatory approaches.

Importance

Inter-agency and internal collaboration are both particularly important for the efficient and effective regulation of services that enable the digital economy and digital platforms. As the range of services and products that are offered online across economies continues to expand, multiple regulatory authorities may have relevant mandates. For example, telehealth services may be subject to regulatory oversight by regulators responsible for ICT, healthcare, and data protection. Similarly, as services that appear similar to end users are delivered by different networks, such as voice communications over broadband connections versus traditional copper wire, different teams within regulatory authorities may address similar issues. In both cases, there is a need for collaboration and coordination to reduce uncertainty and ensure widespread understanding of regulatory roles and positions.

Some regulators have explicitly identified internal collaboration as a central value or principle. For example, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) notes that collaboration is one of the five core values around which all regulatory activities are centered. ICASA’s description of collaboration in its 2023-2024 performance plan centers on internal collaboration, noting that the regulator:

- eradicates silos by developing a mindset that aligns its work with its organizational vision and strategy, and

- creates internal synergies to fast-track organizational performance (ICASA 2023).

Diverse areas of competence

The mandate and powers of a regulatory agency, regardless of sector, are defined by the law or similar instrument by which it is established. For example, the Malaysia Communications and Multimedia Commission’s (MCMC) powers, as defined in legislation, include advising the minister on national policy objectives related to communications and multimedia activities, implementing and enforcing provisions of the communications and multimedia law as well as considering and suggesting reforms to the law, regulating all communications and multimedia activities not included in the law, and supervising and monitoring communications and multimedia activities, among others (Malaysia Government 1998).

Regulatory authorities in different sectors should have defined responsibilities and powers and should be able to provide guidance to each other and to policymakers and other stakeholders within their designated areas of competence. As new technologies, services, policies, and regulatory questions arise, there should be a clear understanding of the regulatory expertise that is relevant and the roles of the different agencies in designing and enforcing policies and regulations.

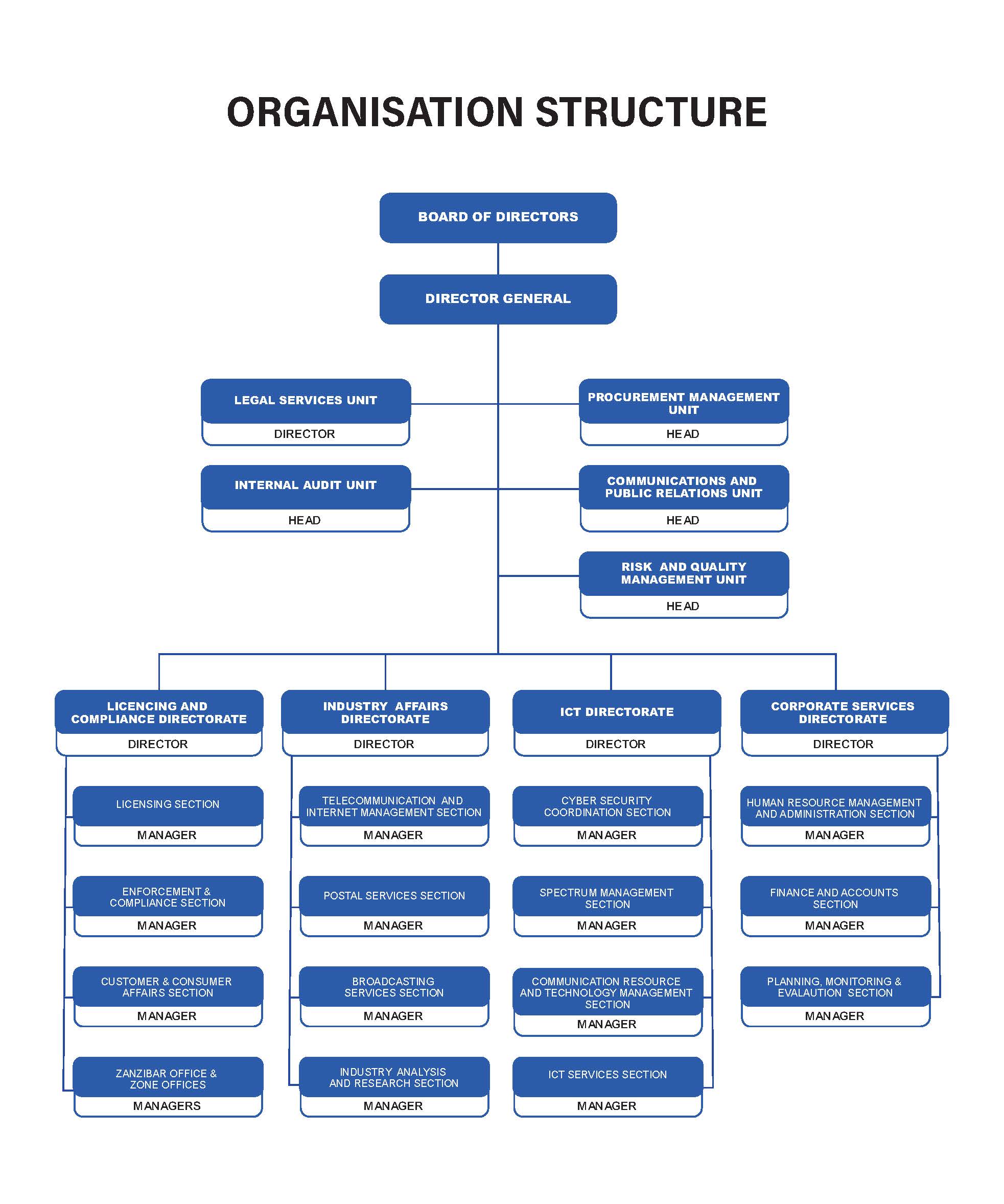

Regulatory authorities each have an internal structure and governance mechanism designed to meet their needs. Many regulators also have an executive board providing strategic direction and operational oversight. Regulators are typically comprised of departments and staff with a wide range of expertise to provide informed oversight and guidance of a complex and dynamic sector. In the case of an ICT sector regulator, these may include, for example, experts focused on the technical characteristics of different types of services and technologies (including fixed, wireless, and satellite communications), broadcasting, spectrum management, international engagement, licensing, and competition, reflecting the mandate of the authority (as illustrated in Figure 1, for example). New areas of expertise have been added to traditional mandates, ranging from online platforms to emerging technologies applications to cybersecurity.

Figure 2. Organizational structure, Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority

Source: TCRA 2022

Regulation of the ICT sector necessarily requires participation by multiple types of expert staff. For example, implementing a policy decision to award new spectrum for use by terrestrial mobile services could involve inputs and actions from experts on wireless technologies, spectrum management, licensing, quality of service, and competition, at a minimum. Regulatory bodies benefit from clear mechanisms by which different departments and experts can coordinate activities to accomplish goals established by policymakers, legal frameworks, or the regulatory agency’s leadership.

In addition, collaboration between diverse expert groups – and frameworks that enable such collaboration – better position the regulator to address novel challenges posed by an evolving sector. As indicated by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) in 2021, an agency framework that enables the agile formation of multidisciplinary teams improves collaboration and the agency’s readiness to respond and pivot to both internal and external changes (ACMA 2021). Such multidisciplinary teams were incorporated into two priorities for ACMA, with the organization also noting that streamlining the use of multidisciplinary teams can grow employee capabilities at all levels.

Improved communication and internal decision support

The adoption of collaboration approaches, such as cross-functional teams, can be valuable tools for organizations – including regulators – to both maximize collective progress toward organizational goals and to improve internal communication. Cross-functional teams are those that include representatives of a variety of departments, areas of expertise, and functions within an organization or across multiple organizations, working collaboratively to address common goals or challenges. In the case of an ICT regulator, as noted above, there may be a need for multiple experts or divisions to participate in the process of awarding new spectrum for a service. However, the same situation applies to multiple areas of regulatory responsibility.

While the composition and operation of cross-functional teams are too varied to result in universal characteristics, there are potential benefits that accrue from collaborative activities across departments or areas of expertise. For example, building lines of communication between different regulators, departments, or teams can reduce the potential for siloing of knowledge and decision-making. Further, regulatory activities or decisions that incorporate inputs from participants across multiple departments or functions reduces the potential for decision-making that results in unexpected or unintended consequences. Similarly, such cross-pollination of information and ideas increases opportunities for multiple constituencies within an organization to ensure that their expertise is incorporated into plans and decisions, thereby increasing buy-in or support for organizational decisions among team members.

Drivers

Multiple factors can lead to regulators adopting, revising, and strengthening collaboration mechanisms. These include ongoing technological developments and convergence as well as more pragmatic organizational factors, such as the merger of multiple entities into a multisector or converged regulator.

Some of the main drivers of internal collaboration are:

- Technological convergence

- Organizational restructuring

- The choice of regulatory approaches (horizontal vs vertical)

Technological convergence

As ICTs have evolved, an increasing number of services are delivered over competing broadband network technologies. Voice communications are now available through broadband-enabled technologies. Content once delivered by terrestrial and satellite television is similarly available through a wide array of providers in both linear and nonlinear formats. This evolution is reflected in the transition from single-sector regulatory authorities to multisector and converged authorities that can simplify administration, licensing, and oversight processes in the ICT sector while also keeping pace with technological advances (ACMA 2021).

Such advances in technology and services have resulted in a growing number of regulators developing competencies in matters that are particularly relevant to online services. These may include cybersecurity, privacy and data protection, artificial intelligence (AI), and online safety. The ability of ICT regulators to develop such frameworks and competencies depends on the relevant legal frameworks, including the laws that establish the regulators themselves. As regulators develop new areas of competence and begin exercising new enforcement powers, additional cross-functional collaborations may be beneficial or necessary.

Given the blurring of distinctions between previously discrete services, it is beneficial for regulatory staff to collaborate and share knowledge regarding technological, market, and regulatory developments that are relevant to multiple agencies or departments. This could be accomplished through the development of cross-functional or specialist teams that address key issues across the organizational structure of the regulator. For example, in preparation for being charged with responsibility for online safety, the United Kingdom’s Ofcom noted that it had developed a program across the organization to ensure readiness for its new responsibilities (Ofcom 2022).

Organizational restructuring

As noted in the ITU/World Bank Digital Regulation Platform module addressing regulator structure and mandate, by 2025 more than 70 per cent of ICT regulators had evolved from sector-specific regulators to converged regulators (ITU 2020). Such restructuring decisions – for example, the merger of South Africa’s telecommunications and broadcasting regulators into ICASA in 2000 or the integration of Saudi Arabia’s telecommunications and space regulators into the Communications, Space, and Technology Commission (CST) in 2022 – may both be driven by and require new collaborative approaches between previously separate regulators.

The roles of technological convergence and organizational restructuring in driving internal collaboration are closely related. As noted by CST, the transfer of responsibility for space regulation to the former telecommunications regulator was a recognition of the importance of the integration of communications, space, and technology matters (CST 2023).

However, the integration of two or more regulators into a converged entity necessitates new organizational structures. To more effectively govern a converging and rapidly changing ICT sector, the converged regulator’s structure should incorporate collaborative mechanisms that leverage the skills of different groups of experts. Thus, a merger or reorganization of the ICT sector regulator provides an important opportunity to reconsider internal structures and organization and to implement new or revised collaborative approaches such as new divisions, cross-functional teams, or committees.

Such reorganizations are not limited only to cases of regulatory mergers. The 2022 changes to the structure of the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to reorganize the International Bureau into a new Space Bureau and a standalone Office of International Affairs were undertaken in response to a changing communications sector and an interest in ensuring agency-wide access to international affairs experience (FCC 2022). In announcing the planned change, FCC highlighted that the separation was intended to allow relevant staff to focus on international communications regulation and licensing and to make their expertise available to any of the seven FCC bureaus that have an international affairs dimension. In parallel, the establishment of the new Space Bureau was a response to technological change, seeking to elevate the significance of satellite programs and policy within the agency to a level that “reflects the importance of the emerging space economy” and to acknowledge the role of satellite communications in meeting domestic communication policy goals. The FCC restructuring thus enabled an enhanced collaboration ability for the agency’s international affairs experts and reflected a changed ICT sector.

Horizontal vs. vertical regulatory approaches

National policy and legislative frameworks frequently include a combination of vertical (or sector-specific) and horizontal (or economy-wide) regulatory agencies. Inter-agency collaboration between vertical and horizontal regulators, such as between an ICT regulator and a consumer protection authority, becomes necessary when a sector-specific regulator has some level of oversight over the same matter addressed by a horizontal regulator.

For example, if an ICT sector regulator has competition-related obligations or powers and a horizontal competition authority is also in place, both authorities will benefit from clarity regarding each regulator’s responsibilities and whether and how they will address competition matters in the ICT sector. This case is discussed further in Deep dive: Collaboration between competition and ICT authorities.

Such collaboration between vertical and horizontal regulators can arise across several issue areas, including privacy, consumer protection, cybersecurity, and safety, among others.

Intragovernmental collaboration mechanisms

Citing the need to address the risks presented by emerging technologies, many government regulators initiate collaboration as a means to deal with novel challenges and coordinate regulatory roles and minimize overlap between agencies. Collaborative efforts among and within regulators have focused on building frameworks around emerging technologies, addressing specific issues (e.g., misinformation, online safety, cybercrime), and modernizing government infrastructure and best practices.

While individual regulators maintain the statutory power to impact regulation and directly enforce their recommendations, collaborative bodies formed by intragovernmental partnerships often lack this decision-making authority. However, they can provide valuable input that influences members’ regulatory actions, as well as offer concrete guidance through working papers, responses to consultations, research conducted in joint sessions, or resources accessible to the public.

Intragovernmental collaboration mechanisms can broadly be classified into two categories:

- formal collaborations among government agencies, and

- informal and project-based collaborations.

Although there are no ”one-size-fits-all” approaches to collaboration, regulators frequently use both formal and informal methods to establish, support, and maintain intragovernmental collaborations. As discussed below in Strengths and Challenges, these approaches offer unique strengths and limitations that should be considered when evaluating opportunities for collaborative governance.

Formal collaborations among government agencies

Formal intragovernmental collaborations are established through written instruments that outline roles, responsibilities, resource allocations, and goals. These instruments can be presented in varying formats and with different levels of specificity, including:

- memoranda of understanding,

- policies or strategies, and

- executive orders or decrees.

Typically, formal intragovernmental collaboration agreements take the form of a memorandum of understanding (MOU), which is used by agencies around the world to enumerate interagency collaborative endeavors. Common elements of collaboration agreements between agencies provides more detailed examples of common components of inter-agency collaboration agreements such as MOUs.

A critical component of MOUs and similar agreements is a clear description of how the participating agencies will work together to effectively oversee and regulate relevant sectors and activities. Even in cases where legislation clearly delineates the roles of, for example, a communications regulator and a competition authority concerning competition in the ICT sector, a formal agreement may describe the processes by which the regulators will consult each other about investigations, merger reviews, market definition, and other matters of common interest. Such arrangements are found, for example, in the memorandum of agreement between ICASA and South Africa’s Competition Commission (Competition Commission of South Africa 2019).

Box 1. Inter-agency ICT collaborative regulation agreements

| Examples of inter-agency collaborative regulation agreements in the ICT sector

Australia: Australian Communications and Media Authority/Office of the Australian Information Commissioner Australia: Australian Communications and Media Authority/Australian Space Agency Brazil: National Telecommunications Agency/Administrative Council for Economic Defense Indonesia: Ministry of Communication and Information/National Consumer Protection Agency Kenya: Competition Authority of Kenya/Central Bank of Kenya Paraguay: National Telecommunications Commission/National Competition Commission South Africa: ICASA/Competition Commission South Africa: ICASA/Film and Publications Board United Kingdom: Information Commissioner/Ofcom United States: Federal Communications Commission/National Telecommunications and Information Administration |

Formal collaborations can also be established through legislative texts and executive orders that define agency roles, responsibilities, and jurisdictions for ongoing collaboration. These can include, for example:

- Policies and strategies, intended to establish national or sectoral priorities and areas of focus. One such example is Pakistan’s Cyber Security Strategy for the Telecom Sector, which notes a need to standardize cybersecurity regulations and frameworks across agencies to avoid duplication and contradiction. The strategy aims to “achieve a unified and standardized cyber security framework across all the sectors” (PTA 2023).

- Executive orders or decrees, such as the U.S. executive order on safe AI development, which tasks the FCC with coordinating with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration to create opportunities for sharing spectrum between government and non-government spectrum operations (The White House 2023).[1]

No matter the origin, these collaborations create clear governance and communication protocols that improve coordination and foster transparency. However, the formal structure can also introduce bureaucratic hurdles that limit flexibility and adaptability in rapidly changing regulatory environments.

In addition to collaboration agreements such as MOUs, government ministries and agencies may engage in more limited formal collaborations intended to achieve particular policy or sector goals (see Table 1 for additional examples).

Table 1. Additional formal collaboration examples

| Country | Participating Entities | Summary |

| Egypt | Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research | A five-year cooperation protocol was announced in 2020 to implement 11 joint projects intended to update educational infrastructure and meet educational priorities |

| Saudi Arabia | CST, General Commission for Audiovisual Media, Water and Electricity Regulatory Authority, Capital Market Authority, Saudi Central Bank, Saudi Data and AI Authority, Public Transport Authority, General Authority for Competition | The National Regulatory Committee facilitates collaboration on ICT and digital issues. 2024 plan included engaging academia and the private sector. |

Informal and project-based collaborations

Informal collaborations are established outside of typical bureaucratic structures and leverage already-existing networks within government to drive impact. They can be fostered through approaches such as communities of practice, working groups, training sessions, and co-located offices to create opportunities for collaboration on issues of shared importance (GAO 2023). Since they are not enshrined in formal agreements, these types of collaborations can also be limited by a lack of resources and decision-making authority, and may be more easily affected by a change in management of the regulator or staff turnover. More specific examples are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Informal collaboration examples

| Country | Description |

| Kenya | The Communications Authority has informal collaboration arrangements with the Consumer Protection Authority and several ministries, including those overseeing health, education, the environment, and economic development. |

| Singapore | The Community of Practice for Competition and Economic Regulations (COPCOMER) has included Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore, Civil Service College, Energy Market Authority, Infocomm Media Development Authority of Singapore, Land Transport Authority, Monetary Authority of Singapore, Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Public Service Division, Singapore Police Force, Singapore Tourism Board, Ministry of Transport |

| United Kingdom | Since 2013 the UK Competition Network (UKCN) has brought together the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and numerous sector regulators, including Ofcom, to strengthen their relationships. To do so, agencies engage in strategic dialogues, cooperate in how to enforce competition law in their fields, and share best practices. |

While these collaborations are not necessarily the result of official cooperative agreements, thorough planning and assessment processes remain critical inputs. Like more formal arrangements, informal collaborations should consider whether it would be practical for regulators to work together or if such arrangements would create undue administrative burdens or workloads. Additionally, when assessing possible collaborations, participants can examine the distribution of available resources between potential collaborators to determine if and how much additional support would be needed. (New York Division of Local Government Services 2008).

Communities of practice

One type of less-formal collaborative mechanism is the community of practice, which can be defined as “A gathering of individuals motivated by the desire to cross organizational boundaries, to relate to one another, and to build a body of actionable knowledge through coordination and collaboration” (World Bank Group 2021). Participants in a community of practice collaborate regularly to exchange information, learn together, develop their skills, and advance general knowledge on the particular topic or issue. Communities of practice are employed in numerous contexts and issue areas, including but not limited to the ICT sector.

As noted in Table 2, Singapore’s Community of Practice for Competition and Economic Regulations (COPCOMER) has included participation by authorities responsible for aviation, energy, communications, transportation, banking, trade, and law enforcement, among others (CCCS 2020). COPCOMER facilitates regular activities, including an annual Regulators’ Tea to discuss competition and regulatory issues, bi-annual half-day seminars, regular newsletters, and training sessions.

Small committees or working groups

Perhaps the most traditional form of informal intragovernmental collaboration is the development of small committees or working groups to address particular matters. These may be established either within a single regulatory authority or between multiple regulatory bodies. In both cases, the underlying objective is to leverage the unique expertise or skills of the participating departments or agencies to address one or more issues relevant to all participants.

In France, Le pôle numérique Arcep-Arcom (the Arcep-Arcom Digital Hub) was established by the regulators responsible for electronic communications (Arcep) and audiovisual and digital communications (Arcom) to conduct technical and economic analysis of the digital markets within each regulator’s remit (Arcep 2023).[2] The Digital Hub is also responsible for convening a monthly committee to protect minors from pornography. In the case of the Arcep-Arcom collaboration, the two agencies signed a formal agreement that governs their cooperation, although this is not always the case (Arcep 2020). Table 3 presents further examples of small committees and working groups.

Table 3. Additional examples of small committees or working groups

| Country | Participants | Basis | Area of focus |

| Australia | Digital Transformation Agency, Department of Industry, Science, and Resources | Unstated | Standards for responsible use of AI within government agencies |

| Egypt | National Telecommunications Regulatory Authority, Central Bank of Egypt | MOU | Enable and expand digital payments |

| Kenya | Communications Authority of Kenya, Central Bank | MOU | Regulation of mobile financial services |

| Nigeria | Nigerian Communications Commission, Central Bank of Nigeria | MOU | Payment systems and financial inclusion |

Larger committees or working groups

In some cases, governments or regulators opt to form multi-agency or multi-department committees or working groups that seek to leverage the expertise of a wider range of regulators or policymakers.

One such approach is to convene a committee or working group intended to focus on one or more specific issues. Such collaborative activities, particularly when established among multiple regulatory authorities, have a public role that includes key outputs and advocacy. The various issues relevant to digital platforms have led to the creation of new issue-focused groups in recent years.

Often explicitly outlined when collaborations are formed, particularly in the case of formal collaborative agreements, the objectives of some groups can include more narrowly tailored areas of focus than others. France’s Digital Hub, as noted, is responsible for convening a broader monthly committee meeting focused on protecting minors from pornography online alongside its cross-agency initiatives. These can be contrasted with Australia’s Digital Platform Regulators Forum (DP-REG), which has a broad scope addressing matters including competition, consumer protection, privacy, and online safety. Outputs such as interagency working papers and submissions to consultations are common among small committees as well as larger collaborative bodies.

As these groups continue to engage in collaborative regulatory activities, the individual regulators will likely build greater familiarity with the various aspects of regulation that affect a particular sector – particularly those traditionally addressed by counterpart regulators – through shared access to information, infrastructure, and staffing. These shared resources enable the participating regulators to gain greater clarity over issues facing their jurisdictions, resulting in more efficient regulatory responses and alignment with other agencies’ actions, when appropriate.

Collaboration can also focus on ensuring the availability of key inputs to enable appropriate sector regulation and development. For example, ICT sector regulators rely upon statistics gathered from multiple stakeholders to develop an accurate view of the sector. Such efforts can include this type of issue-focused cooperation between ICT regulators and national statistical offices, as is the case with Trinidad and Tobago’s National Digital Inclusion Survey, undertaken by the Telecommunications Authority of Trinidad and Tobago (TATT) and the Central Statistical Office (CSO) in 2021 to measure the state of the country’s digital divide and inform universal service projects and other initiatives (Government of Trinidad and Tobago 2021). Similarly, regulatory agencies may collaborate in monitoring and data collection to ensure safe operation of ICT infrastructure, as in the case of a longstanding memorandum of understanding between the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) and the Tanzania Atomic Energy Commission to work together on electromagnetic radiation issues (TCRA 2023).

Training sessions

Workshops and training sessions represent another type of informal collaborative mechanism that can be valuable to regulatory authorities, providing opportunities to learn from each other as well as external experts. Training sessions can be conducted in a wide range of formats on nearly any topic, providing participants with opportunities to learn, exchange information, and engage in exercises and simulations, as well as network with counterparts in other departments or regulatory agencies.

For example, Saudi Arabia’s CST has organized multiple training sessions that bring together a range of stakeholders to learn and exchange information on digital regulatory matters. In 2023, the Advanced Digital Regulatory Program, conducted with ITU, involved the participation of more than 50 specialists representing regulatory authorities as well as service providers (CST 2023). The program was intended to leverage international best practices and experiences, develop national cadres, and enhance the efficiency of the Saudi regulatory environment.

Similarly, in 2021 the World Bank and the Government of Nigeria organized a training session for Nigerian government and regulatory stakeholders on Innovative Business Models for Closing the Internet Access Gap (Voice of Nigeria 2021). The training, based on a World Bank-published report, included several international experts providing information and leading discussions on topics including new technology trends and the different components of the broadband value chain.

Training sessions, particularly those organized by international organizations, can also be structured to include participants from multiple countries across a region or worldwide, further expanding opportunities to learn from regulatory counterparts and to share lessons learned.

Approaches to intragovernmental collaboration

Intragovernmental collaboration can take multiple forms (as summarized in Table 4), each of which will be addressed below.

Table 4. Types of intragovernmental collaboration

| Type of Intragovernmental Collaboration | Example |

| Bilateral or multilateral interagency collaboration | ICT regulator and competition authority |

| National network of regulators/regulatory fora | Digital regulator forum |

| Regulator-Ministry collaboration | National representation in international fora |

| National-local collaboration | Communications infrastructure right of way coordination |

Bilateral or multilateral interagency collaboration

National regulators frequently collaborate on issues in which all participants have a level of responsibility or there is actual or potential overlap. In the case of ICT regulators, collaborative arrangements may exist with authorities responsible for topics including competition, financial services, privacy, and consumer protection, among others. ICT regulators and competition authorities, in particular, frequently enter into collaborative arrangements to clarify responsibilities for addressing competition concerns in the ICT sector. Collaboration between these two types of regulatory authorities is the subject of Deep dive: Collaboration between competition and ICT authorities.

When developing or reviewing collaborative regulatory approaches, it is useful to keep in mind key rationales and principles for such collaboration. These create the appropriate conditions for resource-pooling, avoiding blind spots, consensus-building and buy-in, and policy coherence (Box 2).

Box 2. Collaborative regulation design principles

| ITU core design principles for collaborative regulation (GSR-19)

1. Policy and regulation should be holistic, employing approaches such as cross-sectoral collaboration, co-regulation, and self-regulation. 2. Policy and regulation should be consultation- and collaboration-based. 3. Policy and regulation should be evidence-based. 4. Policy and regulation should be outcome-based. 5. Policy and regulation should be incentive-based. 6. Policy and regulation should be adaptive, balanced, and fit for purpose. 7. Policy and regulation should focus on building trust and engagement. Source: Global Symposium for Regulators (GSR) 2019 Best Practice Guidelines |

National regulatory or policymaker networks

In addition to issue-focused collaborative activities, governments may choose to establish more general, collaborative mechanisms that encompass a larger universe of regulatory authorities. One such example is found in Saudi Arabia, where the National Committee for Digital Transformation established the National Regulatory Committee (NRC). This committee was initially comprised of the regulators responsible for communications, audiovisual media, water and electricity, capital markets and banking, data and AI, public transportation, and competition (CITC 2021).

India’s Joint Committee of Regulators (JCoR) is a collaborative initiative led by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) and described as “a collaborative initiative by TRAI to study regulatory implications in the digital world and to collaboratively work on regulations” (TRAI 2024). The JCoR is comprised of representatives from TRAI, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), and the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, with representatives of the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) and the Ministry of Home Affairs as special invitees. To date, JCoR has focused on issues related to unsolicited commercial communication (UCC).

In the Netherlands, the Digital Regulation Cooperation Platform (SDT) was established in 2021 by four regulators that each deal with digital services: the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM), the Dutch Data Protection Authority (AP), and the Dutch Media Authority (CvdM) (ACM 2024). Member regulators seek to respond to developments in a manner that ensures alignment on topics that can include AI, algorithms and data processing, online design, personalization, manipulation, and deception. The SDT’s objectives are to:

- understand and discuss digital society opportunities and risks, taking advantage of opportunities and addressing risks;

- keep in mind various public interests;

- invest collectively in knowledge and expertise; and

- ensure efficient and effective enforcement of compliance with rules and regulations, including both Dutch and European frameworks.

Notable outcomes within two years of establishing the SDT were the publication of basic principles for effective transparency in online information (ACM 2023a) and basic principles for online marketing to children (ACM 2023b).

Similarly, the UK Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) was established in 2020 to streamline collaboration on digital matters between the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), and Ofcom (DRCF 2024a). As described by DRCF, the forum “supports cooperation and coordination between members and enables coherent, informed and responsive regulation of the UK digital economy.” DRCF activities are governed by terms of reference that set out several characteristics and guiding elements, including its purpose, goals and objectives, membership, budget, and roles and responsibilities (DRCF 2022). Recent DRCF publications have addressed topics including generative AI, immersive technologies, age assurance technologies, harmful design, and quantum technologies. In addition, DRCF publishes transparency and accountability documents, including annual reports and workplans. In June 2023, DRCF established an international regulatory network, the International Network for Digital Regulation Cooperation (INDRC) to foster discussion between regulators across digital regimes and to gather insights into how overseas jurisdictions are approaching domestic regulatory coherence and cohesion.

Documents enabling transparency and accountability, such as those published by the UK DRCF, provide valuable information that allows stakeholders and other interested parties to evaluate the benefits provided by its activities. Additional examples of regulatory networks are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Additional examples of regulatory or policymaker networks

| Country | Committee/Group | Participating Regulators | Basis | Activities and Focus |

| Australia | Digital Platform Regulators Forum (DP-REG) | Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), eSafety Commissioner, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) | Terms of Reference | Streamline regulation, with a particular focus on the intersection of ICT issues related to competition, consumer protection, privacy, online safety, and data issues. |

| Canada | Canada Digital Regulators Forum (CDRF) | Competition Bureau, Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada | Terms of Reference | Exchange best practices, conduct research, and collaborate on matters of common interest, such as artificial intelligence and data portability |

| South Africa | Digital Regulators Forum | FPB, ICASA, Financial Sector Conduct Authority, .ZA Domain Name Authority | Unstated | Understand and respect each other’s regulatory powers and work together in line with global digital collaborative regulatory approaches |

Many groups mentioned here share similar overarching goals. Common themes include a focus on streamlining regulatory approaches, promoting collaboration between different regulators, and improving the sharing of information and best practices. While groups tend to share fundamental principles, differences between these groups center on their attention to specific issues and the types of outputs produced.

Collaboration between regulators and ministries

Recognizing the importance of establishing policy and implementing legal and regulatory frameworks, ministries and regulators both play key roles in the development, evolution, and operation of the ICT sector and other aspects of a country’s economy. While the policymaker and regulator are frequently distinct entities and have complementary roles, it is not uncommon for the two to collaborate. In fact, such interactions may be mandated by law and is not only desirable but essential to ensure alignment of policy vision and its effective implementation.

Regulators may be explicitly tasked with providing advice and counsel to a ministry or government, such as in the case of TRAI India. The legislation establishing TRAI lists the regulator’s functions, beginning with making recommendations to the licensor (currently the Department of Telecommunications, DoT) on a wide range of matters, including licensing, competition, equipment, and spectrum management (TRAI 1997). India’s legal and regulatory framework is characterized by frequent communications between DoT and TRAI, with TRAI consultations incorporating the text of DoT requests and indicating any relevant past communications between the two bodies. As noted above, Malaysia’s MCMC is also charged with advising the minister on national policy objectives, among other duties (Malaysia Government 1998).

Coordination between ministries and regulators can also focus on specific issues. For example, in early 2024, Singapore’s Ministry of Communications and Information (now known as the Ministry of Digital Development and Information) announced that both the ministry and the regulator, the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) have been taking steps to improve online safety for citizens, particularly Singaporean youths. While the ministry worked with technology companies to launch an online safety toolkit, IMDA was preparing to introduce new materials to support parents in guiding children’s online activities (Ministry of Communications and Information 2024).

An important consideration when considering collaboration between an independent ICT sector regulator and a ministry or policymaker, however, is that collaboration or coordination must be carried out in line with the legal framework and should not endanger the independence of the regulator.

Collaboration between national and local authorities

In addition to collaboration between entities at the national level, such as sector regulators or government ministries, the continued development and operation of the ICT sector depends upon coordination between the national regulator and local regulatory authorities. For example, national regulatory authorities may establish regulations that govern the operation of wireless communications towers, while a sub-national authority has authority over the placement, size, or appearance of such infrastructure. Similarly, a ministry may develop and fund a national program to expand fiber-optic cable infrastructure, while permission to undertake road construction or erect overhead lines must be granted by a city council. Coordination and collaboration between entities at the national and local levels is thus an important consideration for the continued development of not only ICT infrastructure, but also for the numerous services and sectors that rely upon connectivity.

In Rwanda, the approval process for new base station infrastructure includes direct coordination between a national regulator – the Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Agency (RURA) – and local authorities. RURA, Rwanda’s independent regulator for utilities including telecommunications, is responsible for ensuring that telecommunication infrastructures do not create adverse impacts on nearby people or environments. In carrying out this responsibility, RURA published guidelines establishing procedures to be followed by operators and service providers in the rollout of base stations, towers, and masts (RURA 2011). The guidelines include notes on the steps for obtaining permits for site building and installation of wireless communication infrastructure. As part of the process, RURA requests zoning clearance and site authorization from the relevant local authority, sharing documents already received from the applicant as well as RURA’s own confirmation that the proposed facility meets RURA’s requirements. Rwanda’s base station permitting process thus explicitly includes a step in which the national regulator coordinates with local authorities to advance the permitting process.

Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada (ISED) has incorporated coordination with local authorities into its requirements applicable to entities that plan to install or modify an antenna system (ISED 2022). The relevant ISED client procedures circular instructs interested parties to contact the local land-use authority to determine local requirements and to follow local authority public consultation processes, if applicable. In the event that the local authority does not have a public consultation process, ISED outlines a default process to be followed.

GSMA, an organization comprised of mobile operators and other mobile sector stakeholders worldwide, has advocated for the development of standardized infrastructure deployment regulations to reduce barriers to meeting coverage needs (GSMA 2018). While GSMA’s recommendations do not explicitly call for collaboration between national and local authorities, the organization suggests responsibilities to be divided between authorities at each level. At a high level, GSMA suggests that the national authority define and provide standardized national procedures for permitting, site modification, notification and consultation, health and safety requirements, and also take steps to maximize access to sites and infrastructure for mobile network infrastructure deployment, while local authorities are encouraged to implement efficient permitting processes, defer to national agencies on policy and technical matters, and follow national health and safety requirements. While stakeholders may differ on the appropriate role for authorities at each level, GSMA’s suggestions demonstrate the range of topics to be addressed in a potential collaborative arrangement between national and local entities.

A level of coordination or collaboration between national and local authorities, such as the arrangements present in Rwanda and Canada, is an important consideration in the ongoing development of broadband infrastructure and the expansion of coverage to reach unserved and underserved populations. A lack of coordination or the presence of unclear or conflicting national and local requirements can inhibit broadband access improvements.

Strengths and Challenges

Collaboration between regulators has become increasingly necessary, especially as the ICT sector has emerged as a key enabler of sectors and activities across entire national economies. Emerging technologies continuously present new issues for regulators to tackle, often blurring jurisdictional lines in the process. Through careful consideration of the type of collaboration desired, intragovernmental collaborations can yield vital contributions to domestic and global ICT regulations.

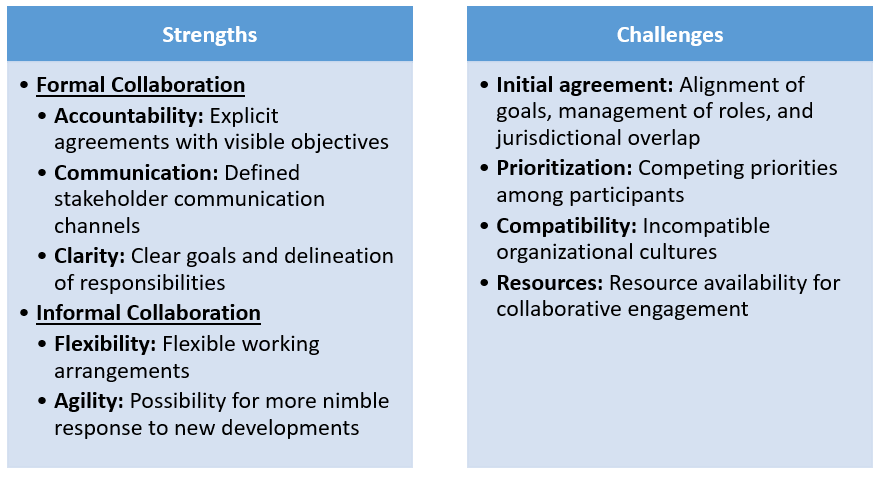

Intragovernmental collaboration activities present both strengths and challenges for regulators and stakeholders. The characteristics in Figure 3 represent examples of potential benefits and obstacles to be considered as regulators and policymakers consider the implementation of collaborative arrangements.

Figure 3. Strengths and challenges of intragovernmental collaboration

Both formal and informal collaborations can provide advantages for regulatory authorities and sector stakeholders. Formal collaborations, based on explicit agreements with support from all participants or a legislative mandate, are characterized by accountability, communication, and clarity. The inclusion of clear objectives can ensure that participating authorities work toward the same goals. Informal arrangements, on the other hand, offer more flexibility to reach solutions and to adjust the parameters of the collaboration as appropriate and as agreed by participants. Such flexibility – as compared to more formal arrangements – may reduce bureaucratic delays and allow more nimble responses to new sector developments, an important consideration for evolving technologies, services, and market conditions.

Both formal and informal collaborations can provide advantages for regulatory authorities and sector stakeholders. Formal collaborations, based on explicit agreements with support from all participants or a legislative mandate, are characterized by accountability, communication, and clarity. The inclusion of clear objectives can ensure that participating authorities work toward the same goals. Informal arrangements, on the other hand, offer more flexibility to reach solutions and to adjust the parameters of the collaboration as appropriate and as agreed by participants. Such flexibility – as compared to more formal arrangements – may reduce bureaucratic delays and allow more nimble responses to new sector developments, an important consideration for evolving technologies, services, and market conditions.

However, in order to secure the benefits of collaborative regulatory activities, stakeholders must take steps to avoid or mitigate certain challenges. Perhaps foremost among the potential obstacles to collaborative regulation is that stakeholders must reach an initial agreement on the parameters of the collaboration. These are likely to include, for example, establishing the stakeholders’ common goals or objectives, identifying and addressing areas of jurisdictional overlap or concurrent regulation, and deciding upon the roles and responsibilities of each participant. Inherent in reaching such an agreement is the need to satisfy each stakeholder’s priorities. For example, competition regulators may focus on different aspects of an issue than a regulator focused more on expanding public access to a service, while both have an interest in ensuring a clear regulatory framework to address anti-competitive behaviors. In some cases, the institutional cultures present in participating entities may influence how effectively they work with one another. Thus, building trust between regulatory entities should be a priority for collaborative activities involving disparate organizational cultures or areas of focus (Waardenburg 2019). Additional issues may arise from funding or resource-related shortcomings on the part of one or more participating entities. Individual regulators or agencies may not have adequate capacity to engage in collaborative efforts, a concern that may be exacerbated in the case of informal collaborative arrangements without dedicated funding.

By considering potential challenges in the earliest stages of planning a collaborative regulatory engagement, regulators and policymakers can maximize the chances that all affected stakeholders will benefit. Ideally, such efforts will result in regulatory frameworks that minimize regulatory blind spots.

Cross-border inter-agency collaboration

In our interconnected world, cross-border collaboration on ICT-related issues is increasingly important to ensure the successful development and implementation of emerging technologies. Considering issues such as spectrum management, cross-border data flows, and artificial intelligence, regulatory agencies often need or seek to work with neighboring countries to foster efficient policy outcomes. This section covers a wide range of approaches to and mechanisms for cross-border collaboration and includes a series of examples to highlight best practices from regulators around the world.

Bilateral regulatory agreements

As discussed in Intragovernmental Collaboration, MOUs are often used by regulators to align agencies on the roles, responsibilities, resource allocations, and goals needed to accomplish a specific policy objective. However, MOUs can also be established between regulators in two or more countries seeking to coordinate on one or more issues of shared importance. The structure of bilateral MOUs is similar to the structure of intragovernmental agreements – they should clearly enumerate how participating governments or agencies will work together to effectively oversee, regulate, and share information on relevant sectors and activities. However, unlike intragovernmental MOUs, these bilateral agreements can focus on higher-level commitments related to knowledge sharing and future coordination in regulation and policymaking.

For example, in 2002, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) and the Lesotho Telecommunications Authority (LTA) signed an MOU to resolve disagreements related to frequency interference, interconnection, and cross-border connectivity (ICASA 2002). The MOU provided a series of cooperative mechanisms to address unique challenges faced by the two regulators with respect to “no-man’s land services” and radio transmission spillover along the border. It also created a forum to bring together regulatory authorities and operators to (a) resolve on-going spillover coverage and frequency interference concerns and (b) create rules and procedures to preemptively avoid these situations moving forward. While this MOU is unique due to the geographic proximity of the two countries, it serves as an example of the ICT-focused challenges that can be addressed through cooperative mechanisms like a bilateral MOU.

In 2021, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) signed an MOU to develop a “global approach” to addressing robocalls, robotexts, and inaccurate spoofing of caller ID (FCC 2021). The document provides a list of objectives, information regarding each agency’s responsibilities and obligations, and procedures related to mutual assistance throughout the duration of the agreement. Both agencies agreed to share complaints and investigatory resources and committed to exchanging knowledge and expertise related to the scope of the MOU.

A more recent example of this type of MOU was signed by Latvia and Ukraine in October 2023. Latvia’s Ministry of Transportation signed a 10-point agreement with Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation to assist with the immediate restoration of broadband internet, support Ukrainian development of ICT infrastructure, and help integrate Ukraine’s ICT sector into European Union infrastructure (Labs of Latvia 2023). The MOU includes commitments to develop an action plan and joint roadmap to carry out the MOU, a timeline for joint events and working meetings of various ICT experts, and a series of procedures for information sharing about best practices.

Bilateral MOUs are a common tool employed by governments or counterpart regulatory agencies (e.g., ICT sector regulators in multiple countries) to address ICT-sector issues. Additional examples are provided in Table 6.

Table 6. Examples of bilateral MOUs in the ICT sector

| Countries | Purpose |

| Senegal and Mauritania | Strengthen measures to reduce cross-border interference and improve telecommunication services in regions along the border between the two countries. |

| Ghana and Togo | Abolish roaming charges between the two countries to decrease the price of mobile services for consumers. |

| Djibouti and South Sudan | Facilitate fiber interconnection through an agreement to connect the South Sudanese capital of Juba to Djibouti. |

| Libya and Egypt | Foster information exchange, technical training, and skills development between regulators regarding fiber optic networks and digital skills. |

As illustrated through the above examples, MOUs can be a useful tool for regulatory agencies seeking to formalize collaborative actions or shared positions with a counterpart in another country on issues of mutual importance.

Multilateral regulatory agreements

Multilateral agreements are formal agreements established between regulatory agencies in three or more countries. These agreements can be broader in scope and can take longer – sometimes years – to negotiate. They emphasize collective action, shared objectives, and close cooperation on issues of global importance. These arrangements can take multiple forms, including regional regulatory associations, digital regulation networks, or regional economic communities.

Once agreed upon, multilateral agreements can take on many different forms. They can result in the creation of a new organization or body, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) or BRICS, or can manifest through a specific agreement or partnership, such as the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Singapore, Chile, and New Zealand. Multilateral organizations such as APEC tend to focus on a broad range of policy priorities relevant to member countries, while multilateral partnerships are often limited in scope and prioritize in-depth discussions related to a pressing public policy issue.

Regional regulatory associations

While multilateral agreements can be negotiated at the global level, they can also take on a more regional focus. Countries frequently collaborate via associations of regulators to advance progress on ICT-related policy issues of regional importance (Table 7). These collaborations can be especially useful for issues such as spectrum management, where regional coordination is essential to ensure efficient outcomes.

Table 7. Examples of regional regulatory associations

| Region | Organization name | Key ICT tracks |

| Africa | West African Telecommunications Regulators Assembly (WATRA) | Promote universal access to broadband and affordability to support the digital economy in West Africa. |

| Arab States | Arab Regulators Network of telecommunications and information technologies (AREGNET) | Facilitate capacity building between members and support ICT sector development in the Arab world. |

| Asia-Pacific | South Asian Telecommunication Regulators’ Council (SATRC) | Address regulatory issues and challenges of common concern in the region to promote harmonious technological development and implementation. |

| Europe | Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) | Improve consistency of EU telecommunications rules and provide advice to European institutions through best practices. |

| Americas | Latin American Forum of Telecom Regulators (REGULATEL) | Foster flexible and efficient cooperative channels to address strategic issues facing the sector in Latin America. |

Outlined below is the full list of active Regional Regulatory Associations by region:

- Africa: Assemblée des régulateurs des télécommunications de l’Afrique Centrale (ARTAC), the Communication Regulators’ Association of Southern Africa (CRASA), and the West African Telecommunication Regulators Assembly (WATRA).

- Arab States: Arab Regulators Network of Telecommunications and Information Technologies (AREGNET) and the Euro-Mediterranean Telecom Regulators (EMERG).

- Asia and Pacific: South Asian Telecommunication Regulators’ Council (SATRC).

- Europe and CIS: Association of Communications and Telecommunications Regulators of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (ARCTEL-CPLP), the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC), the Eastern Partnership Electronic Communications Regulators Network (EaPeReg), the Réseau Francophone de la Régulation des Télécommunications (FRATEL), the Independent Regulators Group (IRG), and the Regional Commonwealth in the Field of Communications (RCC).

- The Americas: Telecommunications Regional Technical Commission, Central America (COMTELCA), the Eastern Caribbean Telecommunications Authority (ECTEL), the Organisation of Caribbean Utility Regulators (OOCUR), and the Latin American Forum of Telecom Regulators (REGULATEL).

In general, regional regulatory associations can serve as important fora for the harmonization of ICT regulatory regimes across member countries. They can also support capacity-building, information-sharing, and strategic planning for future technological developments.

Digital Regulation Network

In 2023, the ITU launched the Digital Regulation Network (DRN) to accelerate global digital transformation. Composed of representatives from various regional regulatory associations, DRN is a new forum for ICT regulators to collaborate on digital policy, regulation, and governance across sectors and borders. DRN initiatives are focused on three primary areas:

- Thought leadership: Serves as a forum for discussions on key regulatory challenges and a venue for strategizing on emerging issues.

- Capacity development: Creates knowledge transfer programs between regional associations and supports institutional capacity-building efforts within regional associations.

- Regulatory experimentation and innovation: Co-designs regulatory and policy frameworks for emerging technologies and promotes cross-sectoral approaches to regulation.

Regulators can engage through their respective regulatory associations by attending meetings, workshops, and training sessions, as well as by participating in visits and knowledge exchange forums to collaborate with other regulatory associations on pressing digital issues.

Regional Economic Communities (RECs)

Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are regional groups that work to foster collaboration between peer countries. RECs in Africa are considered the “pillars” of the African Union (AU) and are designed to facilitate regional economic integration throughout the continent.

Table 8. Sample REC and regional regulatory association ICT programmes

| Regional Economic Community | Sample ICT programmes |

| Arab Maghreb Union (UMA) | Broadband Optical Fibre Telecommunication Network Initiative (Diplo 2022) |

| Caribbean Community (CARICOM) | Data Protection and Privacy Rules (CARICOM 2020) |

| Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) | Enhancement of Governance and Enabling Environment in the ICT sector (EGEE-ICT) in the Eastern Africa, Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean region (EA-SA-IO) (COMESA 2021) |

| East African Community (EAC) | One Network Area (ONA) and the East Africa Regional Digital Integration Project (EA-RDIP) (EAC 2024) |

| Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) | Drafting of convergent regional commitments in the field of telecommunications/ICTs (UN Economic Commission for Africa 2019) |

| Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) | ECOWAS Digital Observatory (ECOWAS 2002) |

| Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) | Initiative to elevate the production and utilization of quality statistics (IGAD 2019) |

| Pacific Alliance | Development of the digital economy, digital connectivity, digital government, and digital ecosystems (Pacific Alliance 2025). |

| Southern African Development Community (SADC) | Regional Infrastructure Development Master Plan (SADC 2012) |

| South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) | Action Plan on Science and Technology and SAARC Initiative for Industrial Research and Development (SAARC 2009) |

Other regional body examples

APEC’s Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system is another example of the convening power of a multilateral organization. APEC—a regional economic forum focused on broadly facilitating cross-border trade—adopted a set of rules in 2011 that balance the flow of data across borders while protecting personal information, as summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. CBPR requirements for certified companies and participating countries

Source: ITU 2020.

As shown in the figure above, the CBPR system includes a wide range of obligations for participating countries, including requiring independent third-party certification of participating countries’ privacy policies. The system is voluntary, so APEC members are not required to join; however, nine jurisdictions have signed on, including Australia, Canada, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore, and the United States.

In some parts of the world, there are regional telecommunications unions that provide regulators with opportunities to engage directly with their neighbors on local issues such as harmonization, roaming fees, frequency interference, and interconnection. Examples of these bodies include the African Telecommunications Union (ATU), the Caribbean Telecommunications Union (CTU), the Inter-American Telecommunication Commission (CITEL), and the European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT). These bodies are comprised of representatives from relevant ICT regulatory agencies and ministries and have a designated Secretariat responsible for administrative and coordinative duties.