Evidence-based approaches in digital policy, regulation and governance

01.09.2025Introduction to evidence-based decision making

As the digital economy expands rapidly in many parts of the world, policymakers and regulators face ongoing challenges in keeping pace with innovative technologies and services that impact ICT markets. The governance of the digital ecosystem represents one of the most complex and dynamic challenges facing policymakers. The rapid pace of technological innovation, the global scale of digital platforms, and the profound societal impact of new technologies demand a regulatory approach that is both robust and adaptive. To address these challenges, many countries are assessing their current regulatory principles and practices to align them with international standards, particularly to ensure good governance and decision-making processes.

As a cornerstone of good policy and regulatory practice in the fast-changing digital economy, evidence-based decision-making (EBDM) is among the key practices that governments may implement to facilitate digital transformation. This approach advocates for the systematic and rigorous use of empirical evidence to inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of policy and regulation, representing a significant departure from traditional models of decision-making that have often relied on anecdote, or political expediency . Policymakers and regulators that take an evidence-based approach can better identify emerging regulatory issues and reach well-informed decisions. EBDM allows “regulators to determine if specific regulatory interventions and decisions are justified by market failures and guide them in defining the desired regulatory outcomes as well as the public policy options to achieve them” (ITU 2020b, 3). The use of EBDM, particularly when combined with robust monitoring, evaluation functions, and collaboration with other competent agencies, “can facilitate effort towards improving regulation and ensuring that the regulation achieves its objectives in the most effective and efficient manner… without imposing disproportionate, redundant or overlapping burden on the market” (ITU 2020b, 3).

International Telecommunication Union (ITU) is supporting countries in developing their EBDM processes through the adoption of best practices, assessment frameworks, benchmarking models on digital transformation, and technical assistance on ICT and digital strategy and regulation. These key benchmarks include the ICT Regulatory Tracker, the G5 Benchmark and, more recently, the ITU Unified Benchmarking Framework as presented in the ITU Global Digital Regulatory Outlook 2023 (ITU 2023a). Built on five policy and regulatory strategies, the Unified Framework focuses on how to adopt and implement “effective, pro-market regulation” that is crafted through a “thorough, evidence-based approach to emerging issues” (ITU 2023a, xii).

Despite the need for an evidence-based approach, ITU found that most regulators worldwide have not yet adopted clear processes for EBDM, which is hindering readiness of digital policy, legal, and governance frameworks for digital transformation. Among Central African nations, for example, ITU found wide disparities between countries’ readiness for digital transformation. While Rwanda was cited as among the more advanced in terms of policy, legal, and governance readiness, progress in other countries, such as the Central African Republic, has been slower to develop and readiness is more limited (ITU 2023a, 44).

Box 1.1. Focus on Central Africa

| Across Central Africa, countries are reviewing the African Union (AU) Digital Transformation Strategy 2020-2030 as a mechanism to establish a regionally harmonized framework for an inclusive digital economy (AU 2020). A key pillar of the AU’s strategy is effective governance solutions to address digitalization and emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), new satellite technologies, and automation. To achieve these new governance approaches, AU recommends that national governments “[r]ethink regulatory approaches and adopt models that are agile, iterative, and collaborative to face the challenges posed by emerging technologies and the fourth Industrial Revolution,” as well as develop “outcome-based regulations” (AU 2020, 43). Regional economic communities such as Communauté Economique des Etats de l’Afrique Centrale (CEEAC) and Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) are also leading digital policy harmonization initiatives to support their member states in advancing their digital markets. |

By incorporating agile and anticipatory regulatory processes, this core module addresses the importance of EBDM and identifies the fundamental principles, frameworks, and tools that policymakers and regulators can incorporate in their decision-making processes to facilitate digital transformation. The topics covered in this core module are highlighted in Box 1.2.

Box 1.2. Topics covered in this core module

|

What is evidence-based decision making and why do we use it?

What is EBDM?

EBDM may be defined as “a process whereby multiple sources of information, including statistics, data and the best available research evidence and evaluations, are consulted before making a decision to plan, implement, and (where relevant) alter public policies and programmes” (OECD 2020a, 9). In the context of digital transformation and regulation, EBDM uses rigorous, data-driven analysis to guide the development, adoption, and implementation of policies and regulations to address the quickly changing digital ecosystem (ITU, World Bank 2024). It also leverages various systems and methodological tools to assess complex technology topics from a policy and regulatory perspective. In 2011, the Government of Rwanda signed a programme of support with the United Nations (UN) to assist the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) with developing Rwanda’s National Evidence-Based Policy, Planning, Analysis and Monitoring and Evaluation (UNDP 2022a). More recently, Canada adopted a government-wide policy that federal regulators must follow when developing regulations, which identifies EBDM as a key principle in which “proposals and decisions are based on evidence, robust analysis of costs and benefits, and the assessment of risk, while being open to public scrutiny” (TBCS 2024a).

Taking a data-driven approach helps ensure that regulatory decisions—both on a forward-looking basis and in enforcement mechanisms— are not arbitrary but based on empirical data and performance metrics to align with policy goals. These practices are often specified in published policies, rules, or guidelines that regulatory authorities must follow. By publishing written decision-making practices that must be followed, policymakers and regulators can further enhance transparency, accountability, predictability, and credibility in the outcomes.

An essential feature of EBDM is the identification of policy options based on available data, evidence, econometric analysis, and strategic foresight, allowing to understand the impacts of regulatory decisions. EBDM supports transparency and accountability in policymaking, helping regulators adapt swiftly to technological advances in the digital economy while maintaining necessary safeguards, such as protecting consumers, promoting competition, and safeguarding privacy.

The use of EBDM is an important tool for governments and other stakeholders to draw alternative scenarios for the application of regulatory instruments and compare their impacts to enable better decisions—also critically reflecting on whether regulatory intervention is needed in certain areas (which is particularly helpful for emerging technologies), monitoring the effectiveness of policy and regulatory decisions, and providing a framework for revising such decisions more efficiently.

Incorporating qualitative and quantitative data from multiple sources—such as stakeholder inputs in public consultations, market performance indicators, other social and economic development datasets, and consumer interests and behavior—EBDM is a crucial tool in agile and anticipatory decision-making processes to ensure that decisions are proactive and adaptable to future developments. This approach not only promotes certainty in regulatory decisions but also encourages sustainable growth and innovation in digital markets.

Types and sources of evidence

As governments incorporate EBDM into their policy and regulatory processes, they can leverage a wide range of evidence from various sources. The notion of what constitutes “evidence” is expansive, enabling diverse kinds of data, tools, and models to be tailored to address specific purposes, such as developing expert analysis to inform the formulation of policy direction and instruments, or using spectrum monitoring tools to inform a spectrum allocation proceeding. Multiple forms and sources of evidence may also be used in a complementary manner to provide greater depth and clarity throughout the decision-making processes and policy implementation.

As detailed in Table 2.1, evidence can be classified into two main types (quantitative and qualitative) derived from two main sources (internal and external). These are not mutually exclusive as various types and sources of evidence are often used within the same proceeding for more robust outcomes. For example, a regulator may first form a policy proposal based on information gathered collaboratively across government agencies (internal data collection) in order to hold a public consultation (external data collection) in which some commenters provide statistical information (quantitative data) while others describe the likely socio-economic impacts of a proposed policy based on international benchmarking (qualitative data).

Table 2.1. Types and sources of evidence used in EBDM processes

| Types of evidence used in EBDM | |

Quantitative data

|

Qualitative data

|

| Sources of evidence/methods for collection | |

External data collection

|

Internal data collection

|

Source: OECD 2012, ITU 2020a.

Principles governing the collection of evidence in EBDM

Regardless of the types or sources of evidence, the data that policymakers and regulators collect should comport with the basic principles described in Table 2.2. These principles include ensuring that the evidence is appropriate and relevant; accurate and credible; and transparent and objective. An EBDM framework is only as strong as the quality of the evidence that feeds it

Table 2.2. Principles and best practices governing evidence collection

| Principles of EBDM | Description |

| Appropriate/ relevant | Evidence should directly address the issue and be fit-for-purpose, focusing on the “importance of ensuring that evidence should be sourced, created, and analyzed in ways that help decision-makers reach policy goals” (OECD 2020b, 29). This also means that the evidence should have local context and applicability. For example, if international benchmarking is used to identify potential policy or regulatory options, benchmarks should be measured against and adapted to local legal frameworks, capacities, and needs. Appropriate and relevant evidence also means that data should be timely as outdated information may not be useful for future-facing policies and regulations. |

| Accurate/ credible | Ensuring that the evidence is accurate and credible is crucial to promoting trust in the outcomes. If the government collects data internally, then the systems of collection should be reviewed to ensure accuracy and integrity, whether it is quantitative or qualitative. When collecting evidence from outside sources, such as public consultations, the provided data should be credible and legitimate. Using multiple consultation rounds can help to improve the data gathered by enabling commenters to respond to each other’s inputs. For example, regulators like the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) and the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) use a two-step process in public consultations where there is an initial comment period, followed by a reply comment period in which initial commenters may support or dispute evidence. |

| Transparent/ objective | Maintaining open, transparent, and objective processes means that the evidence collected should be available and accessible to the public through different mechanisms. Subject to reasonable privacy and confidentiality provisions, the evidence should be made available—at a minimum—on the regulator’s website, social media accounts, and official gazettes. Taking an “open by default” approach to digital government principles further helps regulators act as a “platform” for collecting, organizing, and sharing information. This marks a shift away from “top-down, centralized, and closed decision-making processes –based on ‘black boxes’ and driven by organizational efficiency” (OECD 2020b, 24). |

Source: ITU analysis, adapted from OECD 2020b.

Benefits and challenges of EBDM

Rather than rely on opinions or interests of a limited number of players, EBDM is based on data gathered by policymakers, ideally from a wide array of stakeholders. There is a range of complementary benefits of implementing EBDM into national digital transformation efforts, several of which are highlighted in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1 Selected benefits of EBDM in digital transformation initiatives

|

Sources: ITU, adapted from ITU 2023a; OECD 2021a

Due to the reliance on data, research, and analysis gleaned from a variety of stakeholders, EBDM can lead to more effective digital policies and regulation that is fit-for-purpose and well balanced. In contrast, policy and rulemaking processes that are not data-driven from a range of interested parties can be overly prescriptive or based on political pressure.

EBDM also enables regulatory outcomes to be future facing and adaptive as they are open and agile rather than based on top-down, command-and-control style decision making. Using high-quality data to inform decisions creates a clear roadmap that identifies the reasons and basis for regulatory choices, as well as supports identification of potential future options to consider as new technologies and services come to market. This streamlines decision-making processes to address and facilitate innovation.

A regulatory decision that is based on the available evidence can more easily and quickly be revised to accommodate new technologies and services as the regulator has built a clear record regarding the processes, foundations, purposes, and objectives for that decision. This was the case in a December 2024 decision by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regarding blanket licensing for user terminals of non-geostationary satellite orbit (NGSO) systems.

Box 2.2. U.S. FCC amendments to spectrum rules to promote emerging NGSO systems

| In December 2024, the U.S. FCC amended the spectrum rules to permit downlink use of the 17.3-17.8 GHz band by non-geostationary satellite orbit (NGSO) operators on a “blanket license” basis for fixed satellite service (FSS). This enables user terminals to connect to NGSO systems without operators being required to obtain individual spectrum licenses for each device, thus enabling further innovation in satellite services to benefit consumers. The FCC adopted these amendments fairly quickly after issuing a similar decision in 2022 that geostationary satellite orbit (GSO) systems could use the band for FSS. The proceedings leading to the 2022 GSO decision included extensive compatibility studies to address potential sharing issues of the band across different services. This evidence was useful during the NGSO proceeding as well, in addition to new data collected via multiple rounds of public consultation in 2023-2024. |

Source: FCC 2024.

EBDM also enables decision makers to keep clear records of policy or decision-making processes documenting the reasons and basis for regulatory outcomes and the associated thought process, fostering regulatory accountability, certainty, and credibility in their decisions. Market players that are confident in regulatory decisions are more likely to invest and expand operations whereas decisions that are made opaquely without public inputs or established rationale or are otherwise based on political capture in which decisions appear pre-determined. Similarly, the use of EBDM can improve administrative efficiency and optimize the allocation of resources. For example, regulators are increasingly using real-time spectrum monitoring tools to identify how heavily certain frequency bands are utilized. By using these monitoring systems, regulators can determine if certain bands are congested or available and thus make more informed decisions that result in more efficient and better optimized spectrum utilization, such as mitigating or resolving harmful interference issues while also facilitating spectrum sharing.

The compounded benefits of EBDM highlighted above can improve consumer and market outcomes in the digital economy as policies and regulations are grounded in data. Consumers benefit from EBDM as regulatory outcomes become effective and fit-for-purpose to protect consumers. For example, France’s Electronic Communications, Postal and Print Media Distribution Regulatory Authority (ARCEP) publishes maps that compare operators’ service quality and coverage based on information compiled by third parties—including operator-reported information and crowd-sourced data generated by users—as well as data gathered by Arcep internally through spectrum monitoring equipment. The maps improve consumer information and choice by enabling users to compare operators based on various criteria, including by operator, coverage (3G, 4G, 5G), types of service (voice/SMS or internet), or by internet speed (ARCEP 2024).

On the competition side, EBDM can help foster competitive markets through public consultations that engage a range of diverse stakeholders such as large incumbents, smaller entrants, investors, financiers or civil society to better understand the market dynamics, structure, shares, and practices that impact competition. For instance, an evolving challenge for competition authorities is how to appropriately define relevant markets involving digital platforms. One of the challenges is that traditional competition law considers pricing as a key factor to determine dominance in a relevant market. However, many digital platforms are “free” to end users and thus pricing is not a relevant metric, leading to revisions to traditional competition law that can assess dominance based on other competitive factors, such as data collection.

While policy and regulatory decisions based on evidence gathered from various sources are important, incorporation of EBDM into policy and regulatory decision-making processes also poses challenges. Some of the benefits and challenges with EBDM are highlighted in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3. Benefits and challenges with adopting EBDM processes

| Benefits of EBDM | Challenges with EBDM |

|

|

Source: ITU.

Country examples of EBDM implementation in rulemaking and enforcement

To highlight the above benefits of EBDM, the following country examples demonstrate how ICT regulators and competition authorities are increasingly using EBDM in their regulatory decisions. These include the ICT regulators in India and Rwanda.

India: Recommendations on the regulatory framework for OTT communications

After being directed by the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) in 2016 to address OTT regulation, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) held a public consultation in 2018 on the Regulatory Framework for OTT communication services (TRAI 2018a). The consultation focused on whether to expand the scope of traditional telecommunications regulation to OTT players, such as voice and messaging apps. After the public consultation and multiple targeted discussions with key stakeholders, TRAI issued recommendations to DoT that regulatory intervention was not warranted. During this process, TRAI implemented various EBDM tools to reach a decision on the recommendations, such as stakeholder engagement, data-driven analysis, and international benchmarking, as detailed below.

- Stakeholder engagement. TRAI conducted extensive stakeholder engagement during the consultation process. The initial consultation deadline afforded interested parties more than 30 days to respond (TRAI 2018b). However, TRAI extended the deadline twice due to stakeholder interest in the proceeding. Ultimately, the consultation period closed in January 20219, which enabled nearly 90 commenters to submit inputs. The commenters represented a wide range of interests, including operators, online service and content providers, internet advocacy groups, consumer associations, academia, and civil society.

- Data-driven analysis. In the Recommendations, TRAI summarized key responses from stakeholders submitted during the consultation (TRAI 2020). This demonstrated that TRAI reviewed the information provided by the broad array of commenters to identify common themes and reach a decision. While the summary of responses was a useful tool, further clarification could have been provided to demonstrate how the information collected was used and analyzed to reach the conclusion.

- International benchmarking. TRAI compared the market dynamics and regulatory responses to OTTs in India with the experiences and outcomes in other key jurisdictions, including the European Union, France, Germany, Indonesia, and the United Kingdom, as well as members of the Commonwealth Telecommunications Organization (CTO). International benchmarking is a useful EBDM tool to compare national developments and trends with international approaches and reach well-reasoned decisions that align with international best practices. As the ITU noted, “evidence-based frameworks, such as benchmarks and advanced data analysis, can serve as a compass and a record of practices across countries, regions and time, and can allow for comparison with international best practice” (ITU 2023a, 32).

The annual GSR Best Practice Guidelines and the Digital Regulation Platform also provide rich sources for such benchmarking.

In following the above EBDM practices, TRAI reached well-articulated recommendations with supporting data. Ultimately, TRAI recommended that “market forces may be allowed to respond to the situation without prescribing any regulatory intervention” for OTTs but that monitoring should be ongoing to address any future changes (TRAI 2020, 9). Thus, TRAI’s recommendations in 2020 enabled continuing review of the issues, including in 2023 when TRAI held a subsequent consultation on Regulatory Mechanism for Over-The-Top (OTT) Communication Services, and Selective Banning of OTT Services (TRAI 2023). With more than 200 comments received, TRAI has not yet issued an outcomes paper or recommendations at the time of publishing this material.

Rwanda: Compliance and enforcement guidelines

In 2023, the Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority (RURA) published Compliance and Enforcement Guidelines that provided a clear, comprehensive, and evidence-based approach to how the ICT regulator would monitor compliance and undertake enforcement proceedings (RURA 2023). RURA identified specific objectives of the guidelines, including to “ensure that any action taken is evidence based, proportionate, and transparent,” as well as that regulatory decisions should be made in an “open, transparent, and objective manner” (RURA 2023, 6).

- Data-driven analysis (physical evidence). RURA emphasized the importance of data collection in monitoring, compliance, and enforcement process. This includes the initial information collection through on-site inspections using observation, photos, interviews, and facility walk-throughs.

- Data-driven analysis (digital evidence). RURA also seeks to obtain “as much factual data as is readily available to determine whether the operator complies or not with the license obligations, regulatory requirements.” This is further accomplished by using technology and data analytics, such as:

- Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, smart meters, and other data collection devices to gather performance-related data;

- predictive analytics and real-time monitoring to identify potential problems before they arise (e.g., unusual patterns of usage) or as they are occurring; and

- data visualization tools, such as dashboards, to communicate key performance indicators to facilitate identification of patterns, trends, and areas for improvement.

The collection of physical and digital data to inform compliance-related decisions supports RURA’s principles-based approach to a well-defined monitoring and enforcement process. The fundamental principles include accountability, consistency, proportionality, targeting serious actions, and transparency, collaboration. This evidence- and principles-based approach to enforcement is crucial to ensuring that RURA’s decisions are efficient, fair, consistent, and objectively applied.

Agile regulatory principles and processes to inform evidence-based decision making

Data-informed decision making is one of the key principles for agile and anticipatory regulation, which is important in the digital economy to drive innovation in an inclusive and sustainable manner. Agile regulation “requires a paradigm shift in regulatory policy and governance, from the traditional ‘regulate and forget’ to ‘adapt and learn’” by incorporating “more holistic, open, inclusive, adaptive, and better coordinated governance models to enhance systemic resilience” (OECD 2021b, 1).

This section highlights broader agile regulation principles to contextualize EBDM as one of several important principles within an agile and anticipatory approach to regulatory frameworks. By understanding the principles, practices, and processes underpinning agile approaches to regulation, policymakers and regulators can tailor them to their countries’ particular need. While prioritizing some of the following principles, practices, and processes—such as a focus on EBDM—may be warranted based on a country’s progress toward digitalization, incorporating the full range highlighted below can help ensure a robust regulatory regime primed to enable digital transformation.

Contextualizing EBDM within agile regulatory principles

Various international bodies—ITU, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and World Economic Forum (WEF)—have developed different, but complementary, principles to agile regulation and digital governance. Table 3.1 synthesizes the common elements of these principles and identifies the respective organizations that support them to demonstrate how EBDM practices fit into the wider concepts of agile regulation in the digital context.

Table 3.1. Synthesis of agile regulatory principles from ITU, OECD, and WEF

Sources: ITU analysis based on ITU 2023a, 36; OECD 2019a; OECD 2021a, 2; OECD 2021b; WEF 2020.

As shown above, decisions that are based on data and evidence are a key aspect of agile regulation that is able to quickly adapt to and address the quickly changing digital environment.

Processes of agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision making

The general process to approach agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision making can be broken down into four main steps: gathering evidence, interpreting evidence, applying insights, and conducting ongoing review (World Bank 2019a). These are basic steps that may be used for various purposes and are a simpler framework than conducting a full regulatory impact assessment, which is detailed in section 5.

- Step 1: Gather evidence. When sourcing data, regulators should aim to collect information from reputable sources and ensure that the data is verifiable and replicable. To maximize efficiency and accuracy, regulators may use available data-driven tools, such as rapid response tools (e.g., phone surveys) and portfolio and project management tools, such as project targeting indexes (PTIs) (World Bank 2021). Regulators can also create and/or adjust regulatory management tools and monitoring arrangements including real-time data flows, analytics, and regulatory sandboxes (OECD 2021a, 2).

This stage of the decision-making process should also be collaborative, with regulators drawing upon the knowledge of different stakeholders. Thus, public consultations—with sufficient time for stakeholders to respond—are crucial. Public consultations enable stakeholders to provide high-quality data and more subjective or qualitative information to help inform decisions. Co-creation stakeholder workshops using thinking frameworks or agile methodologies can also provide valuable insights to the decision-making process while developing strong ownership of the final decisions.

Following data collection, regulators should dedicate time to verifying the validity of evidence in the case of data-driven or monitoring tools and to reviewing all stakeholder inputs in the case of public consultations.

- Step 2: Interpret evidence. After gathering evidence, regulators should consider the strength of the data collected. This may be based on a variety of factors including the recency, the source, and means of collecting the data. Various metrics are available for interpreting and contextual data which are highlighted in Table 3.2 below.

Table 3.2. General standards to determine the quality of statistical data

| Standards | Description |

| Utility, relevance, timeliness | The utility of statistical data refers to both the relevance and timeliness of the information. Relevant statistical data will represent the population or circumstances under study and meet current and potential users’ needs. Timeliness means that the statistical data adhere to the intended publication schedule and are sufficiently recent to be useful. For example, when measuring the state of broadband connectivity and penetration rates, regulators may rely on statistics related to data usage, broadband subscriptions, and population or geographic distribution of internet access and adoption. |

| Accuracy and credibility | The degree to which data correctly reflect the real-world situations and are free of errors arising from various factors. In the context of statistics, accuracy means the closeness of the estimated value to that of the true (unknown) value in the population. For example, to ensure that operators meet targets for network build-out, regulators may independently monitor passive and active network infrastructure deployment and cross-check this information collection with reports submitted by operators on network deployments to better track how targets are being met and ensure accuracy of information. |

| Accessibility, transparency, clarity | To the extent feasible, data should be accessible by various stakeholders, including researchers, industry organizations, and the general public. This includes the ease with which users can access the data and the degree to which they are explained through metadata, as well as mechanisms to check for and address potential biases in the methodology, sampling, or other aspects of the statistical analysis process. This may include, for example, regulators publishing detailed reports on mobile network coverage, spectrum usage and level of congestion in certain frequency bands, or quality of service metrics that include the methodologies used to collect and analyze the data, as well as the underlying data used in the analysis. |

| Comparability and coherence | Comparability of the statistical data refers to the degree to which data can be compared across time, regions, or other domains. The data should adequately represent the groups or context under study to enable the conclusions to be generalized appropriately, including to ensure that sample sizes are sufficiently large and diverse. The data should also be coherent in the sense that they are consistent with recognized definitions and methodologies to be applied uniformly. For example, if a regulator conducts consumer satisfaction surveys to help determine whether quality of service targets are being met, they should ensure that the data collected are representative to account for various differences across populations, such as socioeconomic, geographic, educational, and gender differences. |

Source: ITU analysis based on World Bank 2019a.

Regulators may also measure the experiences, preferences, and values of the stakeholders involved through stakeholder mapping exercises. Further, regulators should place potential strategies in context to consider the effect of regulatory or policy decisions on people, industry, and government at the local, national, and international levels. All available tools including regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) should be leveraged, making sure to incorporate principles related to an agile, anticipatory, and outcome based approach (for more on RIAs, see section 5.1 below).

- Step 3. Apply insights. When all collected data has been appropriately interpreted with sufficient consideration of stakeholders and outcomes, the next step is execution of the insights gathered. Rulemaking processes may become more agile to realize efficiency gains, welfare benefits, and future flexibility to update outdated or ineffective policy.

Drawing upon the key indicators provided by the ITU’s Unified Framework, regulators can begin actively evaluating results. Many countries employ regulatory pilots (sandboxes) or different levels of collaborative regulation, including self-regulation, co-regulation, and risk-based regulation, to navigate this space. For example, when designing regulatory sandboxes, the duration for experimentation is typically one to two years with appropriate guardrails and guidance (e.g., reporting to the regulator periodically to update on status and outcomes), limits on commercial availability, quantitative limits in terms of power output or geographic scope. Decisions to use sandboxes or self- or co-regulatory approaches can facilitate high levels of interaction between innovators and regulators.

- Step 4. Follow-up and capacity development. Regulators demonstrate commitments to regulatory decisions by vigilantly monitoring developments and making appropriate adjustments if necessary. Employing the principle of inclusivity and collaboration, regulators can actively engage with stakeholders following regulatory decision through consultations, surveys, or other interactive means. Follow-up plans based on gathered evidence should be effectively communicated to all relevant stakeholders. To ensure sufficient capacity, internal ministries and/or public organizations should continue to build and maintain capacity through dedicated trainings.

Applying the principles: Ireland’s process to combat scam calls and texts

One of the modern nuisances plaguing consumers is the uptick in scam calls and texts, which has increased recently due to the improved technologies and reduced costs of perpetrating this type of financial fraud, such as “spoofing” telephone numbers. In response to increased scam calls and texts—which increased 90 per cent between 2020 and 2021 alone—the Commission for Communications Regulation (ComReg) launched a review of the nuisance communications rules.

Between December 2021 and April 2024, ComReg conducted a comprehensive, multi-step, evidence-based proceeding to revise the rules and better protect consumers. This proceeding exemplifies how an ICT regulator may apply agile regulation principles and use data-driven analysis from a wide range of credible sources, public consultations, RIAs, and other EBDM tools to reach a decision that balances effectiveness with minimal regulatory burdens. Box 3.1 outlines the steps that ComReg applied to reach an iterative, inclusive, adaptive, and evidence-based decision on the matter.

Box 3.1. Ireland’s proceeding to combat scam calls and texts (2021-2024)

| December 2021. ComReg formed the Nuisance Communications Industry Taskforce (NCIT) composed of providers of electronic communications services (ECS)—which ComReg determined to be uniquely positioned to understand scam calls and texts—to discuss potential interventions to mitigate nuisance communications, draft an implementation roadmap, develop effective means for industry collaboration in the long term, and report on their progress to ComReg.September 2022. ComReg issued an update on NCIT’s progress, noting that 15 industry members comprised of large network operators and smaller providers held seven meetings and developed proposed interventions and the roadmap. ComReg further noted that outside consultants had been hired to launch a consultation in 2023 and NCIT would continue to work for several more months, including to conduct a gap analysis on further measures, proactively monitor trends in nuisance communications, and formalize inter-operator and cross-sector coordination.

June 2023. ComReg opened the consultation on combatting scam calls and texts, which set out the context and need for the proposed revised rules. The consultation included the results from the RIA that ComReg conducted to assess the likely effect of the proposed regulation or regulatory change, including whether regulation is necessary at all. ComReg used the results of the RIA to identify preferred options and select the one that would likely be the most effective and least burdensome. The consultation also included the results of the econometric analysis of the victims of fraud via nuisance communications, as well as consumer and business surveys, which were conducted by outside expert consultants. ComReg further used international benchmarking of similar measures adopted in Canada, France, Singapore, and the United States. The consultation was initially scheduled for a six-week period, which ComReg extended for an additional month due to stakeholders’ requests and the scope of the proposed intervention, thus giving ample time for interested parties to submit clarifying questions and provide high-quality information and feedback. April 2024. ComReg published the response to the consultation and issued a final decision. ComReg summarized all evidence and data that had been collected from a wide range of sources and processes, including the consultation comments, RIA, econometric analysis, and surveys. ComReg also identified the next steps, which included monitoring implementation of the interventions, addressing any remaining gaps in the rules, and further public consultations on key details of implementation. |

Sources: ComReg 2021; ComReg 2022; ComReg 2023; ComReg 2024.

Key stakeholders and their roles in evidence-based decision making

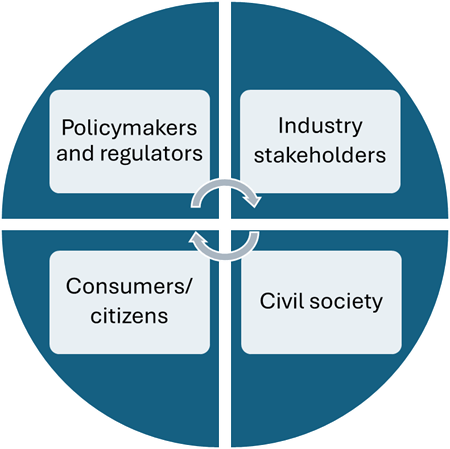

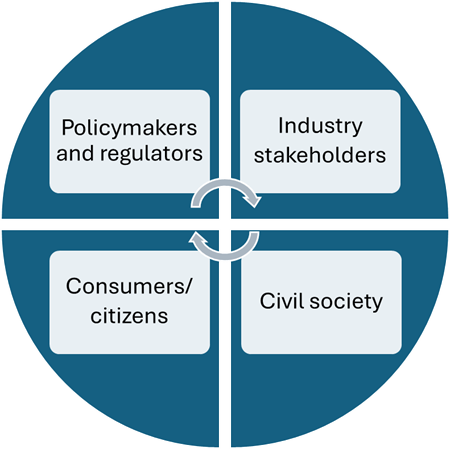

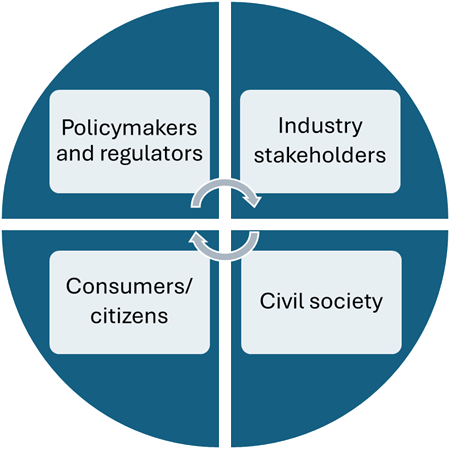

This section identifies the key players in EBDM processes, including policymakers and regulators, industry players and organizations, civil society, and individuals acting in their capacity as consumers and citizens, as shown in Figure 4.1. Effective processes for agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision making rely on these key players to coordinate and provide valuable insights and information for well-balanced, inclusive, and adaptive policies and regulatory frameworks.

Figure 4.1. Key players in agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision making

Policymakers and regulators

Policymakers and regulators play a crucial role in facilitating digital transformation by acting as objective arbiters in decision-making processes (ITU, World Bank 2020). The use of EBDM is one of the key mechanisms to achieving a more structured and neutral approach to adopting and implementing policies and regulatory frameworks, including to ensure that decisions are made according to open, transparent, and inclusive processes that consider all stakeholder interests. However, the roles and responsibilities of policymakers and regulators are broader than simply issuing decisions. They are also responsible for setting clear targets, strategies, frameworks, and practices that will guide the digital transformation process. Continuous monitoring and evaluation are also vital functions that policymakers and regulators play throughout the EBDM process. Ensuring sufficient oversight of policy implementation can allow regulators to adapt and intervene in cases where regulatory objectives are not being met. Table 4.1 highlights some of the fundamental roles and responsibilities of policymakers and regulators when making decisions that impact the digital economy.

Table 4.1. Roles and responsibilities of policymakers and regulators

| Roles | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Establish clear vision, targets, strategies, and plans | Set digital policy agendas and ensure that initiatives and strategies to facilitate digital transformation are aimed at maximizing socioeconomic benefits for all, including to address access, affordability and accessibility of digital technologies and services to all, particularly for vulnerable populations. |

| Create harmonized, enabling frameworks | When modernizing policy and regulatory regimes for the digital age, focus on adopting and implementing adaptive, future-focused, principles-based frameworks that foster innovation while managing risks to consumers. Such frameworks should also consider promoting innovation through experimentation and regulatory sandboxes. |

| Engage stakeholders in decision-making processes | Prioritize inclusive engagement of stakeholders to encourage collaboration across sectors, including well-structured public consultations that provide ample opportunity and time for all interested parties to respond. The feedback gained from consultations is also data-rich, providing evidence from a wide range of stakeholders that regulators can use for better decision-making and outcomes. |

| Adopt streamlined, incentive-based rules and principles | Rather than adopt prescriptive, burdensome rules, foster innovation and investment through incentive-based regulation that focuses on outcomes and seeks to reduce administrative costs by eliminating bureaucratic hurdles. |

| Monitor and enforce policies and regulatory decisions | Ensure that new or revised policies and regulations are monitored and reviewed to evaluate whether they are fit-for-purpose, as well as enforce rules in a manner that is proportionate to alleged contraventions. |

| Conduct education and awareness initiatives | Publish guidance that targets various stakeholders, including consumers and industry players, to provide up-to-date and easy-to-understand information regarding how the policy and regulatory frameworks impact them. |

Source: ITU.

Industry players

Industry stakeholders refer to all market players in the digital ecosystem. These include more traditional ICT providers that offer domestic services to end users, which may be private or state-owned entities, large incumbents, or small new entrants, or offer any type of service or technology, such as terrestrial mobile, fixed line, or satellite-based services. Industry players also include international connectivity, such as subsea cables, and backbone and middle mile infrastructure, such as content delivery networks and data centres. Other industry players impacted by digital regulatory efforts include online content and application providers and digital platforms.

While industry stakeholders are not positioned to establish policy and regulatory decision-making processes, they do play key roles with important responsibilities in how policies and rules are adopted (ITU, World Bank 2022). Table 4.2 highlights some of these roles and responsibilities.

Table 4.2. Roles and responsibilities of industry players

| Roles | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Stay informed and engaged | Take a proactive approach to understanding the policy and regulatory environments, including review of government websites and sources of information for planned legislative and regulatory initiatives. Industry players should also engage consumers, providing relevant and useful information to enable consumers to make informed choices. |

| Participate in consultations, outreach, and reporting | Submit inputs to consultations and participate in stakeholder engagement and validation workshops, particularly to provide important insights and evidence to support the relevant positions and enable regulators to make more informed decisions. This may include providing commercially sensitive information where regulators include confidentiality provisions to promote disclosure during consultations and other targeted outreach. Industry participation is an important avenue to share knowledge and expertise that may not otherwise be available to policymakers and regulators. Licensees should also comply with mandatory reporting obligations to provide regulators with further information regarding types and scopes of services and networks offered, which can help achieve connectivity goals. |

| Coordinate and collaborate | Leverage opportunities to coordinate with other market players through industry associations, as well as collaborate with regulators, such as through self- or co-regulatory frameworks, voluntary codes of practice, or public-private partnerships. |

Source: ITU.

Civil Society

Civil society plays an important role in policy and regulatory discourse as they function independently from governments and the private sector while representing wide swathes of community, citizen, and consumer interests (World Bank 2024). Considered the “third sector” in addition to the public and private sectors, civil society includes, for example, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community organizations, academia, and consumer advocacy groups, with a focus on influencing and promoting policy initiatives. These groups impact decision-making processes by holding policymakers and regulators accountable, particularly as they often advocate for vulnerable or underserved populations.

In some ways, the roles of civil society in agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision-making processes are similar to those of industry players, such as participating in consultations and seeking opportunities to collaborate. However, the responsibilities of civil society may differ as they advocate on behalf of others rather than on behalf of their own interests. Some of the main roles and responsibilities are highlighted in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3. Roles and responsibilities of civil society

| Roles | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Stay informed and engaged for effective advocacy | Because civil society represents the interests of others, such as marginalized or under-represented groups, they should stay informed about the needs of the groups and interests they represent. This may include community-level organization, as well as education initiatives to help inform citizens about pressing matters that impact them. Civil society is well positioned to explain the risks and benefits of new digital technologies to consumers, thereby providing guidance and advocacy to vulnerable communities. |

| Participate in consultations and outreach | Work with policymakers and regulators through public consultations and targeted outreach to advocate for fundamental rights and beneficial socioeconomic outcomes. As the “third sector,” civil society can offer valuable insights and data beyond technical or financial considerations. |

| Coordinate and collaborate | By engaging the communities that they represent while also coordinating with policymakers and regulators, civil society can act as a bridge between the public and private sectors to help develop effective, inclusive, and human-centred policy and regulatory frameworks. |

Source: ITU.

Consumers/citizens

Including individuals—as consumers and citizens—in decision-making processes has been one of the more challenging aspects of implementing agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision making (UKRN 2017). While in competitive ICT and digital markets, consumers tend to “vote” through their purchases, it may be more difficult for consumers to feel like their voices are heard as individuals. For example, individuals may not be aware of how various policies and regulations impact them and may not know about consultations or other avenues for discussions with policymakers and regulators.

Despite these ongoing challenges, it is becoming easier for individuals to participate in decision-making processes, particularly as consultations and other outreach efforts are conducted online with simple mechanisms for open participation. This may include, for example, participating in targeted consumer campaigns that involve responding to questionnaires or surveys or otherwise staying informed about online safety and privacy protections (UKRN 2017). Consumer protection associations are also becoming increasingly valuable stakeholders in policy discussions, with some associations, such as the Uganda ICT Consumer Protection Association, focused specifically on the ICT sector. Table 4.4 identifies some of the roles and responsibilities that individuals have in decision-making processes.

Table 4.4. Roles and responsibilities of consumers/citizens

| Roles | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Improve digital literacy | Individuals should leverage online platforms, portals, and educational portions, often published on websites of policymakers, regulator, and civil society, to improve their digital literacy. This may include learning new digital skills to identify online mis- or dis-information, avoid online fraud and scams, and protect themselves and their families from online harms. |

| Stay informed and engaged | Individuals should stay informed and engaged. This includes responding to regulators’ public consultations and other outreach mechanisms, such as questionnaires, surveys, and hearings or events (whether in-person or virtual) to better influence policies and regulations early in decision-making processes. |

| Join advocacy groups | Individuals may join consumer or digital rights advocacy groups in order to have their collective interests represented. Such groups can help to amplify individual voices in support of consumer protection initiatives. |

Frameworks, tools, and techniques and their use in EBDM

This section focuses on the frameworks, tools, and techniques that policymakers and regulators may use to improve decision-making processes. The main focus is on implementing regulatory impact analyses or assessments (RIAs) as a crucial tool in EBDM, supported by country case examples of how regulators in various regions have adopted and implemented RIAs in their jurisdictions. This section also examines other tools and techniques that policymakers and regulators may use as part of EBDM processes.

Regulatory Impact Analysis as a tool to improve decision making in the ICT sector

ICT regulators adopted at the Global Symposium for Regulators 2024 (GSR-24) Best Practice Guidelines, which identify 19 measures and guiding principles to consider to “create an environment conducive to positive outcomes for all stakeholders, fostering innovation, trust, and social welfare” (ITU 2024a, 3). The first guiding principle calls for ICT regulators to take a “proactive approach” to balance innovation with risk minimization. This includes adopting “agile, adaptive, and anticipatory regulatory frameworks, applying innovative regulatory approaches such as regulatory sandboxes, regulatory impact assessments (RIA), collaborative regulation, horizon-scanning exercises, and evidence-based decision making” (ITU 2024a, 3).

RIAs are a useful decision-making tool as they enable policymakers and regulators to reach better-informed decisions. By applying a systematic process in which the potential effects of a proposed policy or set of rules are evaluated, the likelihood of unintended consequences can be reduced. As the OECD noted, the goal of RIAs is to improve the design of regulations through the identification and evaluation of the “most efficient and effective options—including non-regulatory options—before making a decision” (OECD 2019b, 70).

Good practices in conducting a RIA

Reviewing a wide range of options, including to forbear from imposing rules, is a critical component of RIAs that separate this tool from other types of EBDM. The most important aspect of conducting RIAs is to take an objective approach without assuming or pre-determining outcomes. Box 5.1 identifies several good practices to consider when organizing and conducting a RIA.

Box 5.1. Good practices for conducting RIAs

| No one-size-fits-all RIA model. Selecting the appropriate and relevant RIA model will depend on the “institutional setting, the sector of application, the type of legal rules subject to RIA, the most appropriate set of methods, and procedure changes.” For example, relying on industry KPIs measuring sustainability may not be relevant for a RIA concerned with broadband connectivity.RIAs are not a panacea. RIAs should not be relied on as the only mechanisms in EBDM but should be incorporated as part of an overarching “holistic approach” to policy- and rulemaking cycles that also incorporates cost-benefit or other analysis models and other agile regulatory principles. As an accompanying measure, regulators may pursue regular follow-up with stakeholders through mechanisms such as public consultations.

RIAs require sustained political commitment. The main benefits of RIAs take time to realize and thus require sustained political commitment from the highest levels of government. Regulators’ first experiences with conducting a RIA may not achieve the desired results and can take some experimentation and capacity building to learn to draft good RIAs. Benefits outweigh costs. While there are costs and learning curves to overcome, well-crafted RIAs can “significantly contribute to the efficiency, transparency, accountability and coherence of public policymaking.” By providing a holistic overview of the regulatory issue at hand backed by empirical data, regulators can better chart a clear path forward. Good governance is essential. In order to conduct effective RIAs, it is essential for good governance institutions to be in place. This includes independent and effective regulatory bodies, reliable legislative planning, adequate skills and a results-oriented mindset in the administration, and strong involvement of external stakeholders. RIAs are well-suited to ICT/digital sectors. Because ICT regulators often possess technical and economic expertise, they are well-positioned to consult stakeholders. Further, RIAs provide a useful platform for regulatory authorities to identify and discuss short- and long-term impacts of regulation in terms of balancing efficiencies and stakeholder interests as well as outlining alternative scenarios for regulatory response to emerging technology applications for example. Use RIAs through a multi-criteria analysis. ICT regulators should aim to “quantify and monetize the direct and indirect impacts of regulation and scrutinize available alternatives” to harmonize specific regulatory initiatives with the regulator’s long-term agenda. Engaging in technical analyses, such as econometric, benchmarking, or trend analyses, can help to better inform priorities. |

Source: ITU 2014, 38-39.

Phases of conducting a RIA

As shown in Table 5.1, conducting RIAs takes place in six phases. Notably, the RIA phases described below complement, rather than replace, the EBDM process/steps identified above can be used to buttress the gathering and interpretation of evidence to apply insights and identify next steps.

Table 5.1. Phases of a regulatory impact assessment

| Phase in the RIA process | Description of the phase in the RIA process |

|---|---|

| 1. Problem definition | Step 1 involves identifying or defining the problem that has been alleged by the policymaker, regulator, or stakeholder. From an ex-ante perspective, policy or regulatory problems are typically categorized into one of two groups: market failures or regulatory failures. For alleged market failures, issues may include “informational asymmetries, barriers to market entry, monopoly power, transaction costs, and many other market imperfections that lead to inefficient outcomes.” Alleged regulatory failures include a broader range of policy and regulatory matters that may entail updating or repealing existing rules or otherwise considering whether to introduce new rules to address new policy objectives or innovations. |

| 2. Identification of alternative regulatory options | In Step 2, policymakers and regulators review the need for intervention considering all regulatory options. This typically reflects the positions of a wide array of stakeholders (meaning that an initial public consultation likely precedes the RIA to gain stakeholder inputs). The potential regulatory options range from potentially more stringent rules to more light-touch or principles-based regulation, as well as options for self- or co-regulation. The option for “no regulation” should also be included. |

| 3. Data collection | Step 3 entails data collection, which is the most crucial phase as it provides the basis for EBDM. Data should come from a variety of sources and methodologies. This includes:

In addition to the above data collection mechanisms, policymakers and regulators can also use economic modelling that offers a simplified representation of the real world to assist with decision-making processes. |

| 4. Assessment of alternative options | Step 4 assesses the options identified in step 2 to resolve the alleged problem in step 1, supported by the data collected in step 3. Depending on the types of data collected in step 3, the assessment can be qualitative, quantitative, or a mix of both. There are various mechanisms to assess alternative options—the most common are cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-benefit analysis, or risk analysis.

|

| 5. Identification of the preferred policy option | It is not until step 5 that the policymaker/regulator identifies the preferred policy option, only after the potential options have been adequately assessed. Importantly, this does not mean that the decision-making process is complete or that the preferred option will be the final decision. At a minimum, further consultation should be conducted to gather stakeholder feedback on the preferred/ proposed policy or regulatory option before any final decisions are adopted. |

| 6. Provisions for monitoring and evaluation | Step 6 recognizes the iterative and forward-looking nature of EBDM. Rather than “regulate and forget” under more command-and-control frameworks, more agile regulatory approaches—including in the RIA model—specify how the selected policy and regulatory outcomes will be monitored over time. For example, if a regulator determines that regulatory intervention is not currently warranted, a timeframe for review may be included as market dynamics or technological innovation develop. |

Sources: ITU, adapted from ITU 2014, 1-2; UNDP 2022b; OIA 2023, World Bank 2019b.

The amount of time to complete these steps varies widely and depends on various factors, such as the regulator’s access to resources and requied procedures, the selected methodologies, the depth and complexity of the problem, and the level of stakeholder participation. Generally speaking, regulators can expect a full RIA to take at least several months to complete. Costs associated with RIAs also vary widely and can depend on the extent that in-house staff or outside consultants are relied upon, as well as the depth and breadth of the RIA.

While many countries require regulators to conduct RIAs prior to adopting impactful regulations, such processes pose certain challenges. Similar to those identified in section 2.4, RIAs pose various challenges to regulators in terms of being resource intensive and costly from a financial, time, and staffing perspective. Regulators must be sufficiently funded and possess the requisite technical expertise in order to plan for, conduct, and implement the outcomes of a RIA. The collection of evidence from a wide variety of sources also means that trustworthy document and data management practices are in place, along with tools to help sort and analyze vast amounts of data. Further, because agile regulation is not “one off” but requires an iterative approach as market dynamics and technologies evolve, such financial and staffing resources must be available on an ongoing basis.

Other tools and techniques for EBDM

While RIAs are powerful and versatile tools for informing policy and regulatory decision-making processes, other tools and techniques can be used to complement, supplement, or replace the full RIA process, enabling policymakers and regulators to better tailor such tools to the specific issues. Understanding when and how to employ the appropriate tools for certain situations and the trade-offs for each can help regulators reach more effective solutions quickly while minimizing costs.

Data collection and analysis tools

Building on section 2 regarding the types (qualitative vs. quantitative) and sources (internal vs. external) of data to be used during the EBDM process, this section focuses on how these types and sources of data may be implemented. Depending on the objective and resource constraints, regulators may incorporate various data collection and analysis tools into their decision-making processes, including public consultations, regulatory sandboxes, and artificial intelligence.

Public consultations

Public consultations are a well-known and vital tool for facilitating stakeholder engagement and evidence collection. Determining the parameters for public consultations—such as issues addressed, structure, targeted stakeholders, and duration—will depend on various factors, such as the stage in the decision-making process, significance or scope of the policy or regulatory proposal, and resources available to the regulator. In crafting a consultation, the scope, costs, capacities, and any other resource limitations should be considered. This may include, for example, the extent to which the following may apply:

- whether internal staffing is sufficient or outside experts/consultations should be hired;

- any translation or other services may be needed;

- any travel-related or event-hosting expenses requirements;

- the established budget and what other funding mechanisms may be available; and

- how information will be collected, such as a dedicated online portal for consultations or comments sent to a specified email address.

For example, some countries establish a government-wide public consultation portal as a “one stop shop” mechanism (e.g., Brazil’s “Participia+Brasil” platform). However, other national regulators, such as the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, typically instruct stakeholders to submit comments to designated email addresses rather than an online portal. The mechanism used to submit comments may also impact how regulators manage and analyze the data sets.

Further, tailoring public consultations to the relevant stage of the policy or regulatory cycle can lead to more valuable insights for regulators. More informal styles of consultation processes may be preferred during the initial and final stages of decision-making processes. These may take the form of in-person public hearings, as well as virtual workshops or seminars in which stakeholders participate orally. These less formal settings are often used to complement formalized consultations in which written responses are provided. Because such consultations enable regulators and stakeholders to provide more robust responses in written form, they are appropriate during key milestones, such as seeking feedback on regulatory proposals.

A key takeaway for public consultations is that they may be used in flexible and adaptive ways to meet the needs of the issue at hand, procedural stage of decision making, and resource or capacity requirements or limits. Developed in collaboration between ITU and UK Ofcom, the Guide to Meaningful Public Consultations will offer further details on practical steps and best practices for constructing an effective public consultation.

Regulatory sandbox

Regulators are increasingly establishing regulatory sandbox frameworks to promote innovation and competition, address regulatory barriers to innovation, or learn about developments in the marketplace. These sandboxes are an “alternative regulatory tool that allows innovators to test emerging ICT products and services in a controlled environment under supervision of the” regulatory authority (CA 2023). In addition to fostering innovation, regulatory sandboxes offer valuable data sources that can inform future policy decisions, both in terms of what has and has not worked during testing phases. These data points may then be used to identify areas in which existing regulations should be amended or rescinded to account for new technological or market developments, as well as identify whether there is a need for new regulatory decisions (ITU 2023b). Box 5.2 highlights how Kenya is using quantitative and qualitative data generated in the new sandbox framework to promote ICT innovation and improve regulatory outcomes.

Box 5.2 Kenya: Regulatory sandbox for ICT innovators

| Kenya’s Communications Authority (CA) established a regulatory sandbox framework for ICT innovators in 2023, including to set up an online Sandbox Portal that facilitates application submissions. Applicants may submit sandbox projects across a range of sectors, products, and services, such as telecommunication solutions, cybersecurity tools, IoT devices, and e-health solutions. Data collection plays a key role as all sandbox participants must submit interim reports throughout the testing period and a final report once exiting the sandbox framework. The information provided in these reports includes KPIs, statistical data, key milestones, issues observed during the testing period, actions to address those issues, and final conclusions. The CA uses the quantitative and qualitative data generated during the sandbox period to make evidence-informed decisions to improve the regulatory landscape. |

Source: CA 2023.

While a useful data collection tool and mechanism to spark innovation, regulatory sandboxes do require oversight and engagement with participants through the entire process, which can make them resource-intensive initiatives. Prior to carrying out regulatory sandboxes, regulators should consider resource allocation for each stage of the process. Alternatives to regulatory sandboxes include test or experimental licenses, innovation testbeds, and innovation hubs (ITU 2023b).

Artificial intelligence (AI)

Advances in AI present regulators with new opportunities to collect useful data while vastly improving the capacity to analyze large data sets at potentially lower costs. While the range of AI applications for regulatory data collection and analysis is emerging, AI is already demonstrating utility in managing and extracting insights from large data sets, such as summarizing and reviewing inputs from public consultations, and automating internal regulatory processes. Governments across Africa, for example, are introducing AI technologies to improve regulatory processes. These include Cameroon and Uganda, as shown in Box 5.3.

Box 5.3. Use of AI in enforcement and decision making in Cameroon and Uganda

| Cameroon: Collaborative regulators forum leverages AI for cross-sectoral enforcementThe Cameroon Forum of Regulatory Institutions (FIRC), which is a collaborative forum composed of several regulators spanning such sectors as ICT, energy, and transportation, announced in January 2025 that it would tap into AI capabilities to assist cross-sectoral enforcement efforts (ANTIC 2025). FIRC’s goal is to change the way regulatory tasks are approached by identifying trends, predicting outcomes, and making decisions precisely and quickly.

Uganda: AI and Big Data projects for evidence-informed decisions In collaboration with ITU, the Ministry of ICT and National Guidance recently launched the Big Data and Artificial Intelligence Landscape Assessment projects. Through these initiatives, the government seeks to leverage AI and big data to improve delivery of ICT services through data-driven, informed decision making (MoICT&NG 2023). Key objectives include to analyze gaps in infrastructure, legal frameworks, and human capacity in order to provide actionable recommendations on future strategies and pilot projects. |

Sources: MoICT&NG 2023; ANTIC 2025.

While AI has the potential to bring unprecedented efficiency gains for ICT regulators, these tools are in nascent stages and untested on a long-term basis. It is important to ensure that any data and analyses that are informed or generated by AI tools remain subject to human oversight and review to ensure that they are accurate, relevant, and free from bias.

Benchmarking tools

As defined in the ITU’s forthcoming policy brief on Leveraging Benchmarking for Evidence-Based ICT Policy Making In Central Africa, benchmarking is “a structured approach that enables countries to evaluate their digital infrastructure, policies, and outcomes against global or regional best practices.” Benchmarks offer data-driven insights to inform better decision making through different types of evaluations, such as comparative analysis and trend analysis, as discussed further in section 5.2.3.

Each type of benchmark offers different insights based on subject matter and geographical focus. Some benchmarks, such as the ITU Unified Benchmarking Framework highlighted in Box 5.4, measure the maturity and development of governance and regulatory regimes. Other benchmarks, such as the World Economic Forum’s Network Readiness Index, are tailored specifically to measure ICT-related KPIs. Such KPIs serve as helpful metrics for establishing progress toward ICT-related objectives. For example, regulators can use KPIs to track year-over-year progress, perform longer-term trend analyses, or benchmark progress to strategic goals (ITU 2021a).

Box 5.4. Overview of ITU’s Unified Benchmarking Framework in support of EBDM

| The Unified Framework combines ITU’s established tools for assessing policy, regulation, and governance in telecom and digital markets, particularly the ICT Regulatory Tracker and the G5 Benchmark (ITU 2023a, 42). Together, these tools provide a set of benchmarks that policymakers and regulators can use to determine the readiness of their countries for digital transformation, as well as compare themselves with their peers in key areas and build tailored roadmaps for future reforms.EBDM tools and processes play a key role in the ITU Unified Framework, with impacts across multiple benchmarks and indicators that highlight how data-driven analysis is important in the adoption and implementation of decisions. Under the third benchmark regarding good governance, for example, EBDM tools apply to the indicator regarding whether there is a formal requirement for RIAs before regulatory decisions are made (ITU 2023a, 94). EBDM also plays a role in the thematic benchmark on Stakeholder Engagement, including mandatory public consultations designed as a tool to gather feedback for decision making and mechanisms for regulatory experimentation. Indirectly, EBDM also impacts other benchmarks, such as regulatory capacity, collaborative governance, legal instruments, and market rules. |

Source: ITU 2023a.

Regulators can use benchmarking in various capacities, including to compare local data points with international benchmarks to identify regulatory or market gaps and progress toward policy goals. Regulators can also construct bespoke benchmarks using predetermined indicators tailored for certain situations. For example, Egypt Vision 2030 includes a Sustainable Development Strategy (SDS) that established a range of KPIs to measure the country’s economic, social, and environmental progress (SDS 2016).

Developing comprehensive international benchmarks can be resource intensive. To reduce time, costs, and staffing resource needs, regulators may leverage existing benchmarking analyses and indices compiled by international and other stakeholder organizations, which are often published on an annual basis. A non-exhaustive list of publicly available international benchmarks is highlighted in Table 5.2 and identifies the relevant organization and benchmark, purpose of the benchmark (e.g., digital readiness or cybersecurity), and an overview of the benchmark’s metrics.

Table 5.2. ICT and digital economy-related international benchmarks

| Benchmark | Purpose | Metrics |

| GSMA Digital Africa Index | Measures digital integration across different types of users and organizations across Africa. | Considers digital consumers, businesses, and government, measuring regulatory maturity based on licensing, consumer protection, taxation, network deployment, and public policy. |

| ITU G5 Benchmark | Comprehensive survey of countries’ progress in digital transformation and readiness. | Structured around four pillars: national collaborative governance; policy design principles; digital development toolbox; and digital economic policy agenda. |

| ITU ICT Regulatory Tracker | Assists regulators with understanding the evolving ICT regulatory landscape. | Uses four clusters of indicators including regulatory authority; regulatory mandates; regulatory regime; and competition framework for the ICT sector. |

| OECD Digital Economy Outlook | Macroeconomic data can identify digital economy trends, opportunities, and challenges. | Draws on indicators from the OECD Going Digital Toolkit, the OECD ICT Access and Usage databases, and the OECD AI Policy Observatory. |

| OECD Indicators of Regulatory and Policy Governance | Provides indicators related to regulatory and policy governance. | Assesses regulatory policies; stakeholder engagement and transparency; RIAs; and ex-post evaluations, |

| World Economic Forum Network Readiness Index (NRI) | Measures country readiness for digital transformation. | Bases NRI ranking on four pillars including technology, people, governance, and impact |

Sources: GSMA 2023, GSMA 2024, ITU 2022, ITU 2024b, ITU 2024c, NRI 2024, OECD 2024, OECD 2015, Partnership on Measuring ICT for Development 2022, UN 2024.

Technical analysis

As defined in the ITU’s forthcoming policy brief on Leveraging Benchmarking for Evidence-Based ICT Policy Making In Central Africa, benchmarking is “a structured approach that enables countries to evaluate their digital infrastructure, policies, and outcomes against global or regional best practices.” Benchmarks offer data-driven insights to inform better decision making through different types of evaluations, such as comparative analysis and trend analysis, as discussed further in section 5.2.3.

After collecting relevant data, regulators can engage in technical analysis to derive actionable insights that may be applied to future decisions. As shown in Table 5.3, various types of analysis may be used depending on the issue at hand and resources available. For example, comprehensive econometric analyses are helpful when estimating likely economic impacts but do require more resources than other types of analyses. However, less resource-intensive analyses, such as comparative or trend may be useful in wider contexts to understand current and past trends. Thus, the options may be tailored to the specific needs of the task, levels of staff expertise, and capacity to outsource the analysis.

Table 5.3. Benefits and challenges related to different methods of technical analysis

| Type of analysis | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

| Comparative analysis |

|

|

|

| Econometric analysis |

|

|

|

| Trend analysis |

|

|

|

Sources: ITU 2018, ITU 2021b, ITU 2023c, ADB 2020.

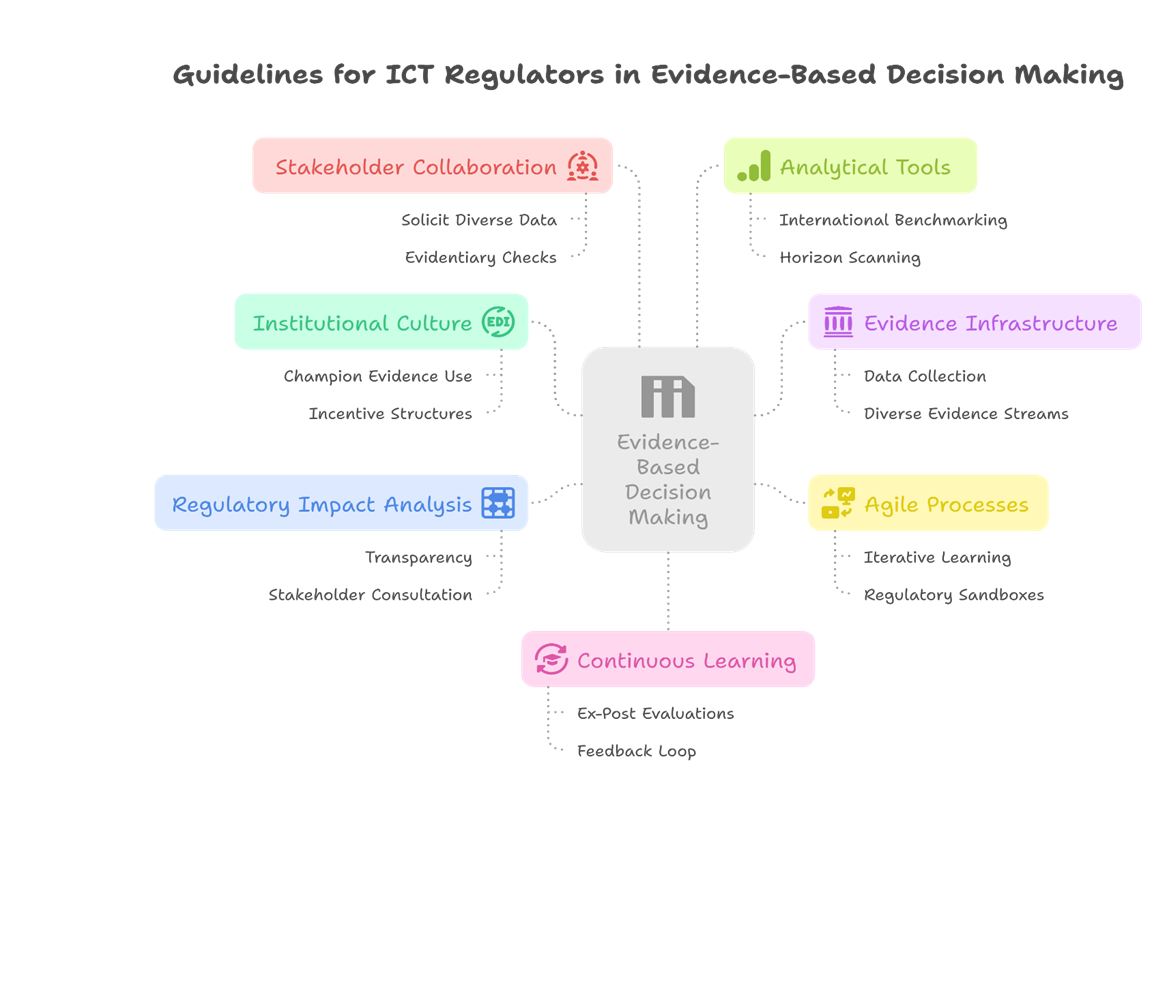

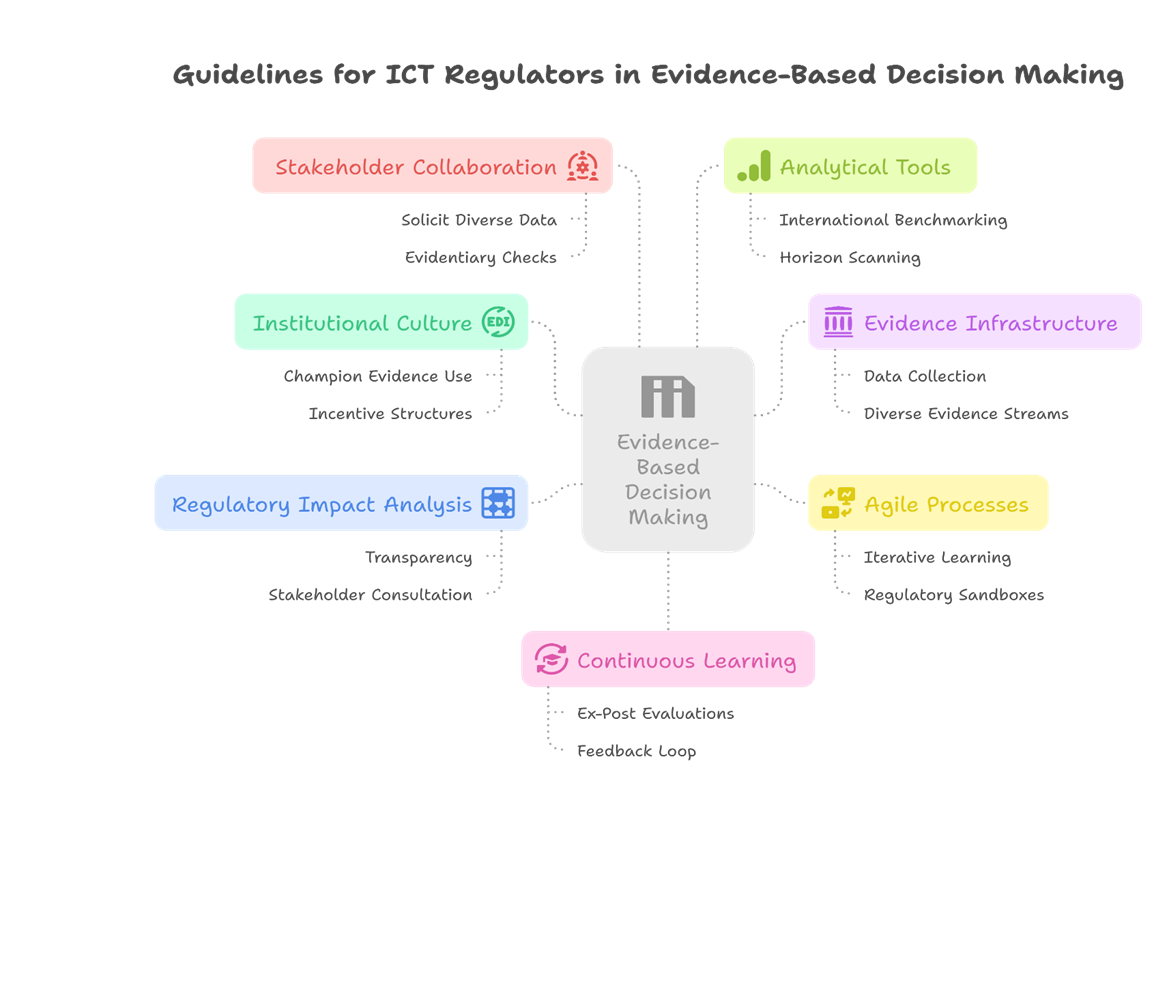

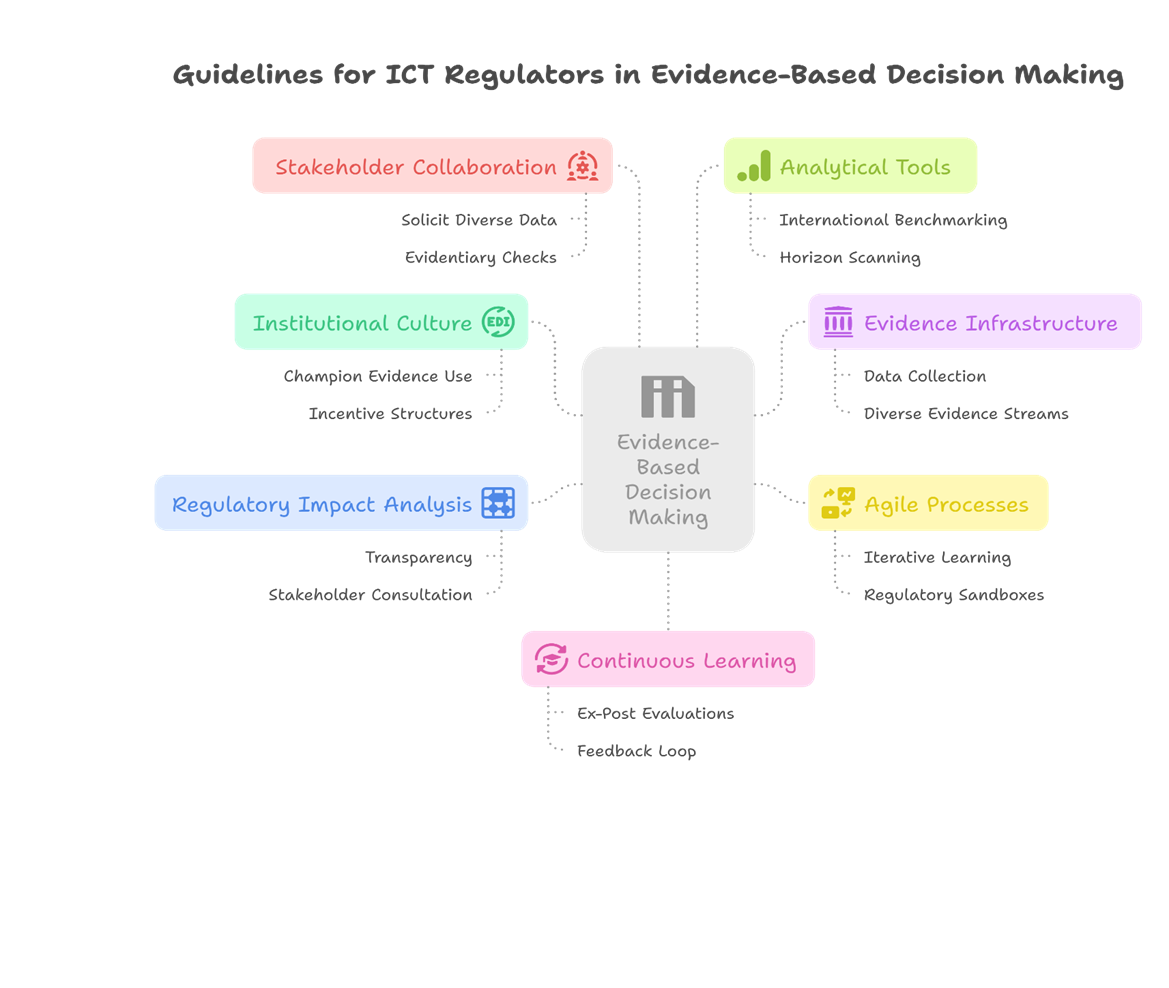

Guidelines for ICT regulators to apply evidence-based decision making

While governments can take different approaches to implementing agile, anticipatory, and evidence-based decision making, they are based on common elements. Synthesizing the principles, processes, tools, and experiences detailed throughout this report, a set of actionable guidelines emerges for ICT regulators seeking to build, sustain, and enhance their capacity for Evidence-Based Decision Making. These guidelines provide a strategic roadmap, moving from foundational cultural shifts to advanced implementation strategies, designed to equip regulators for the complexities of the digital age.

Guideline 1: Cultivate an Evidence-First Institutional Culture. The foundation of EBDM is not a tool or a process, but a culture. Regulatory leadership must unequivocally champion the use of rigorous evidence, prioritizing it over ideology, or inertia. This involves establishing a clear, high-level mandate for evidence use and creating incentive structures that reward evidence-informed analysis.

Guideline 2: Build a Robust and Diverse Evidence Infrastructure. A culture of evidence must be supported by a robust infrastructure. Regulators should invest in building in-house capacity for data collection and analysis. A mature evidence infrastructure systematically integrates diverse streams of evidence, including industry-supplied data, consumer complaints, academic research, and international benchmarks.

Guideline 3: Adopt Agile and Anticipatory Processes. In the fast-moving digital sector, static EBDM is insufficient. Regulators must embed their evidence-based practices within an agile governance framework. This means shifting from linear rulemaking to iterative cycles of learning and adaptation, using tools like regulatory sandboxes and phased implementations to turn the act of regulation itself into a tool for evidence generation.

Guideline 4: Systematize the Use of Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA). RIA should be institutionalized as a mandatory gateway for all significant regulatory proposals. To prevent RIA from becoming a perfunctory box-ticking exercise, the process must be transparent, involve meaningful stakeholder consultation, and be subject to independent quality oversight.