Financing universal access to digital technologies and services

11.10.2021The pandemic has opened the door to the use of digital technology in ways never before imagined and given real meaning to the prefixes “e-”, “remote,” “virtual,” “online” and “distance.” During this time, digital technology has been crucial – for those with access. While on the one hand, the crisis has led to the fast-tracking of digital adoption in countries that already had some level of digitalization; on the other, it has exposed digital inequalities, which are particularly large in less developed economies. Never has the impact of the digital divide been so glaring.

A sense of urgency was already felt as countries sought to meet fast-approaching deadlines for the meeting of national broadband targets and digital transformation strategies linked to the global attainment of the SDGs by 2030. Now, with economies still battling the effects of COVID-19 and some still in the throes of second and third waves, many countries are seeking to stimulate post-pandemic recovery through infrastructure investment. Past experience from the global financial crisis of 2008/2009 has shown that recovery will need to be facilitated by public investment, both financial and non-financial. Governments will have to find ways to ensure economic growth and productivity by harnessing innovative business models and strategies that support the expansion of broadband networks, as well as digital adoption, use and inclusion.

Over the last 20 years, as the digital sector has evolved and become more central to people’s lives, there have been significant shifts in the approach to funding universal access. These shifts have occurred in the broader development financing sphere, as well as specifically in the infrastructure space, and need to be reflected in the public broadband and digitalization funding mindset. Whether it is pooling financial resources, sharing open-access infrastructure or leveraging public money to raise private funds, the goal is to stretch limited financial and non-financial resources as far as possible. To that end, key trends include:

a) Using a combination of monetary and non-monetary, or in-kind, contributions, based on project needs and the various strengths of collaborative financiers;

b) Making smarter investments and thus a move away from “funding” (out of a moral imperative) to “financing,” which is more commercially grounded and relates to making good investments, while contributing to socio-economic development;[1] and

c) Collaboration between governments, commercial banks, development finance institutions (DFIs), the private sector and bilateral and multilateral donor organizations to meet funding gaps is increasing, including through blended finance or the strategic use of development finance to mobilize additional finance for sustainable development in developing countries.

The ITU report provides the context for the collaborative and high-impact universal access financing required to bridge the digital divide. It explains why broadband and digital transformation matter, i.e. for economic growth and inclusion, and that a key factor that deters investment is risk. There are several types of risk to be mitigated – governments have a key role to play in reducing macro-economic, political and regulatory risk, which will in turn reduce costs and increase investment. Financing priorities are explored, as are the potential funders for digital transformation. It is noted that there are myriad potential financiers for universal access and that public money should only be used where private capital does not intend to go, or where the injection of public money will bring about a significant step change without distorting competition.

The report addresses the fact that the funding gap is not monolithic and considers the different gaps that exist, in terms of gender, infrastructure and schooling, and the challenges that the significant costs of closing them pose. It is acknowledged, however, that in the medium term, the most significant funding gap, in quantum, is the one related to the deployment of broadband networks that support digitalization. Although the costs related to encouraging adoption, use and innovation are low relative to infrastructure deployment and maintenance costs, the associated risks are higher. Furthermore, all costs must be dealt with in parallel to create a people-centred and holistic user experience. Ultimately, it proposes that the fundamental funding policy and regulatory challenge is to make servicing rural and low-income areas and populations worth the investment risk for the private sector and co-investors.

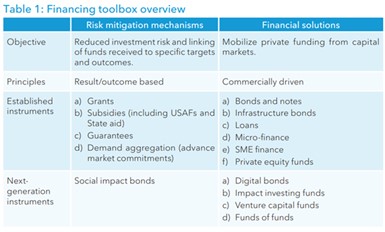

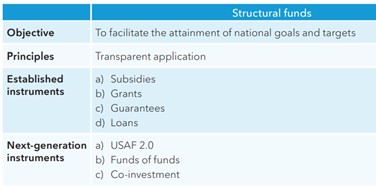

The financing toolkit and the principle of blended finance as a means of mobilizing private investment are explored. This is an important approach that carries through the rest of the report. Various funding instruments are discussed with a particular focus on structural funds, including universal service and access funds (USAFs).

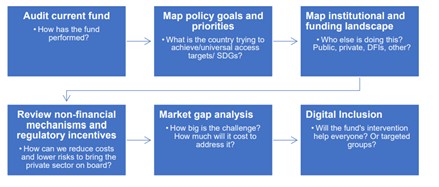

The fund journey has been bumpy, so much so that in many countries it is time to rethink the concept and institution. It provides alternative fund models, including co-investment funds and funds of funds, which have achieved some level of success in addressing more high-risk financing, such as for SME development and accelerators. Elements from these models are proposed as well as a way forward for “USAF 2.0” as the scope extends beyond infrastructure to digital transformation. Of course, just as there is no single financing solution for universal access, there is no single response to the question about the role and relevance of the 100 USAFs currently operational across the world, nor is there a single model for any future USAF 2.0. Solutions will differ according to the country context and each fund’s historical performance, which is informed by its legal and institutional framework and administrative and operational capacity, in addition to a number of other factors that are explored in the report.

Steps to review Funds

The discussion also turns to the non-financial mechanisms that are available to mitigate risk – regulatory and policy incentives. Collaboration, pooling and leveraging are key themes – as much for non-financial incentives as for financial approaches. To that end, this section suggests some policy and regulatory actions that can assist in encouraging investment in infrastructure and promoting adoption, innovation and digital inclusion. They range from “dig once” and “dig smart” policies, which address infrastructure investment challenges, to regulatory sandboxes, which can facilitate innovation. All the regulatory measures in this section, including regulatory forbearance, are discussed as means of lowering costs, reducing risk and ultimately facilitating financing.

Programmes, projects and practices are also examined. It focuses on business models for deploying various supply and demand-side projects and initiatives, ranging on the supply side from traditional public-private partnerships (PPPs) to bottom-up community-based wireless broadband models. On the demand side, the practices are wide ranging and address gaps in digital literacy and adoption by individuals, households, strategic public institutions (e.g. schools and hospitals) and SMEs. Filling these gaps requires innovative thinking that shifts the focus from connecting people to networks to connecting people to other people via networks.

In conclusion, this report emphasises that, given the various funding gaps, the myriad funders and financiers and the significant capital requirement, pooling, collaboration and cooperation will be central to financing universal access to digital technologies and services. In addition to the infrastructure funding challenges for high-cost, low-margin, rural and remote areas and underserved communities, there are additional funding requirements relating to facilitating people’s participation in the digital era, i.e. digital adoption, innovation and digital inclusion. Ensuring the effective participation of vulnerable and marginalized communities, in particular, needs to be intrinsic to all universal access initiatives and projects. The economic cost of exclusion is higher than the cost of closing the infrastructure, affordability, gender and other gaps that persist as the world becomes increasingly digitalized.

To access the full report click here.